13.1 Sexual Dysfunctions

Sexual dysfunctions, disorders in which people cannot respond normally in key areas of sexual functioning, make it difficult or impossible to enjoy sexual intercourse. Studies suggest that as many as 30 percent of men and 45 percent of women around the world suffer from such a dysfunction during their lives (Lewis et al., 2010). Sexual dysfunctions are typically very distressing, and they often lead to sexual frustration, guilt, loss of self-

sexual dysfunction A disorder marked by a persistent inability to function normally in some area of the sexual response cycle.

sexual dysfunction A disorder marked by a persistent inability to function normally in some area of the sexual response cycle.

Rates for sexual behavior are typically based on population surveys. What factors might affect the accuracy of such surveys?

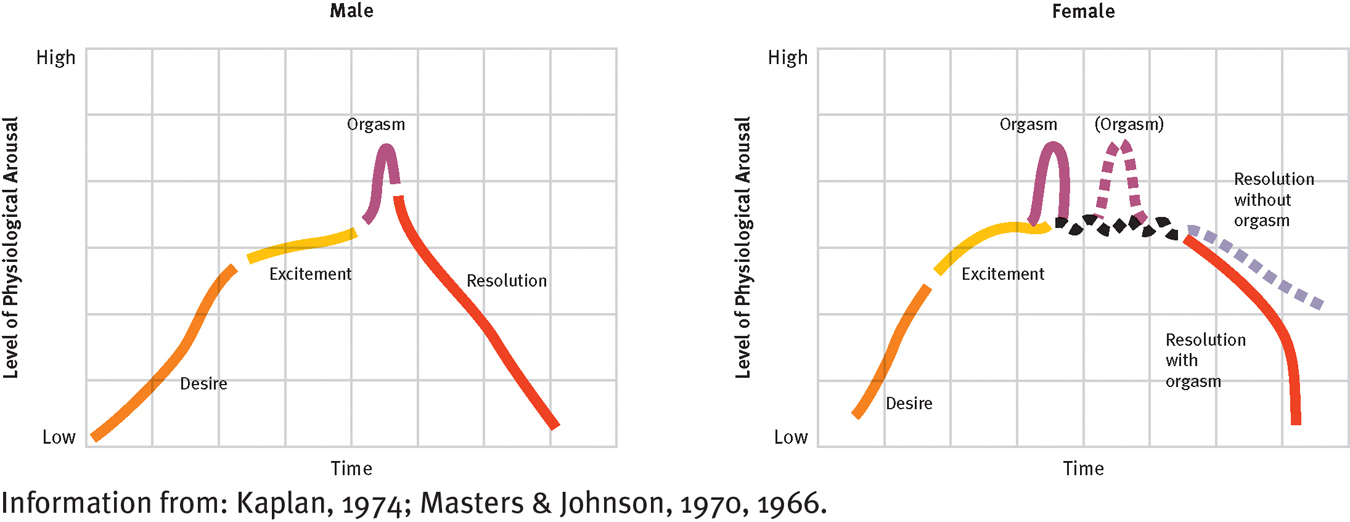

The human sexual response can be described as a cycle with four phases: desire, excitement, orgasm, and resolution (Hayes, 2011) (see Figure 13-1). Sexual dysfunctions affect one or more of the first three phases. Resolution consists simply of the relaxation and reduction in arousal that follow orgasm. Some people struggle with a sexual dysfunction their whole lives (labeled lifelong type); in other cases, normal sexual functioning preceded the dysfunction (acquired type). In some cases the dysfunction is present during all sexual situations (generalized type); in others it is tied to particular situations (situational type) (APA, 2013).

The normal sexual response cycle

Researchers have found a similar sequence of phases in both males and females. Sometimes, however, women do not experience orgasm; in that case, the resolution phase is less sudden. And sometimes women have two or more orgasms in succession before the resolution phase.

Disorders of Desire

The desire phase of the sexual response cycle consists of an interest in or urge to have sex, sexual attraction to others, and for many people, sexual fantasies. Two dysfunctions affect the desire phase—

desire phase The phase of the sexual response cycle consisting of an urge to have sex, sexual fantasies, and sexual attraction.

desire phase The phase of the sexual response cycle consisting of an urge to have sex, sexual fantasies, and sexual attraction.

A number of people have normal sexual interest but choose, as a matter of lifestyle rather than sexual desire, to avoid engaging in sexual relations (see InfoCentral below). These people are not diagnosed as having one of the sexual desire disorders.

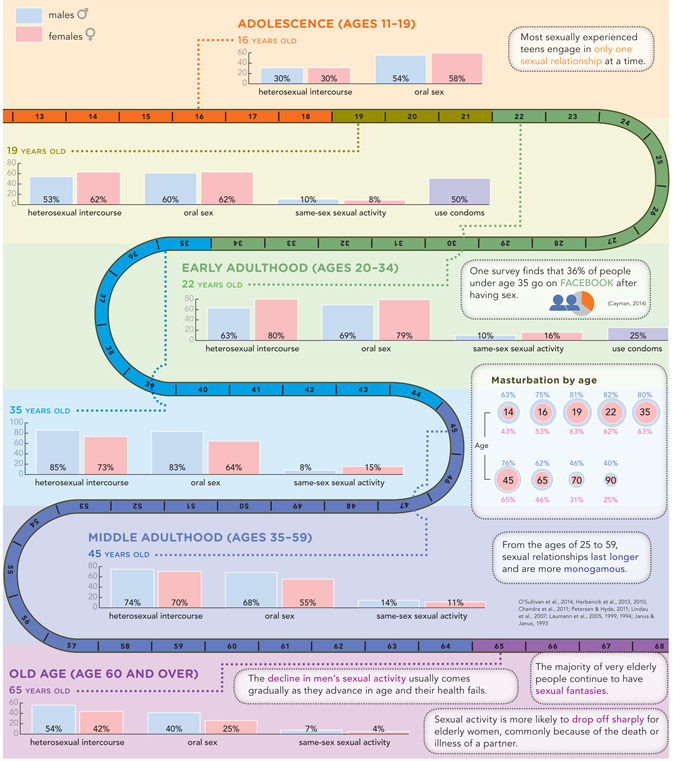

InfoCentral

SEX THROUGHOUT THE LIFE CYCLE

Sexual dysfunctions are different from the usual patterns of sexual functioning. But in the sexual realm, what is “the usual?” Studies conducted over the past two decades have provided a wealth of enlightening information about sexual behavior in the “normal” populations of North America. As you might expect, sexual behavior often differs by age and by gender.

Men with male hypoactive sexual desire disorder persistently lack or have reduced interest in sex and engage in little sexual activity (see Table 13-1). Nevertheless, when they do have sex, their physical responses may be normal and they may enjoy the experience. While most cultures portray men as wanting all the sex they can get, as many as 18 percent of men worldwide have this disorder, and the number seeking therapy has increased during the past decade (Martin et al., 2014; Lewis et al., 2010).

male hypoactive sexual desire disorder A male dysfunction marked by a persistent reduction or lack of interest in sex and hence a low level of sexual activity.

male hypoactive sexual desire disorder A male dysfunction marked by a persistent reduction or lack of interest in sex and hence a low level of sexual activity.

|

Male Hypoactive Sexual Desire Disorder |

|

|---|---|

|

1. |

For at least 6 months, individual repeatedly experiences few or no sexual thoughts, fantasies, or desires. |

|

2. |

Individual experiences significant distress about this. |

|

Female Sexual Interest/Arousal Disorder |

|

|

1. |

For at least 6 months, individual usually displays reduced or no sexual interest and arousal, characterized by the reduction or absence of at least three of the following: • Sexual interest • Sexual thoughts or fantasies • Sexual initiation or receptiveness • Excitement or pleasure during sex • Responsiveness to sexual cues • Genital or nongenital sensations during sex. |

|

2. |

Individual experiences significant distress. |

|

(Information from: APA, 2013.) |

|

Women with female sexual interest/arousal disorder also lack normal interest in sex and rarely initiate sexual activity (see Table 13-1 again). In addition, many such women feel little excitement during sexual activity, are unaroused by erotic cues, and have few genital or nongenital sensations during sexual activity (APA, 2013). As many as 38 percent of women worldwide have reduced sexual interest and arousal (Christensen et al., 2011; Lewis et al., 2010; Laumann et al., 2005, 1999, 1994). It is important to note that many sex researchers and therapists believe it is inaccurate to combine desire and excitement symptoms into a single female disorder (Sungur & Gündüz, 2014). They would prefer that DSM-

female sexual interest/arousal disorder A female dysfunction marked by a persistent reduction or lack of interest in sex and low sexual activity, as well as, in some cases, limited excitement and few sexual sensations during sexual activity.

female sexual interest/arousal disorder A female dysfunction marked by a persistent reduction or lack of interest in sex and low sexual activity, as well as, in some cases, limited excitement and few sexual sensations during sexual activity.

A person’s sex drive is determined by a combination of biological, psychological, and sociocultural factors, any of which may reduce sexual desire (Berry & Berry, 2013; Carvalho & Nobre, 2011). Most cases of low sexual desire are caused primarily by sociocultural and psychological factors, but biological conditions can also lower sex drive significantly.

Biological Causes of Low Sexual DesireA number of hormones interact to help produce sexual desire and behavior (see Figure 13-2 below), and abnormalities in their activity can lower a person’s sex drive (Giraldi et al., 2013; Laan et al., 2013; Rubio-

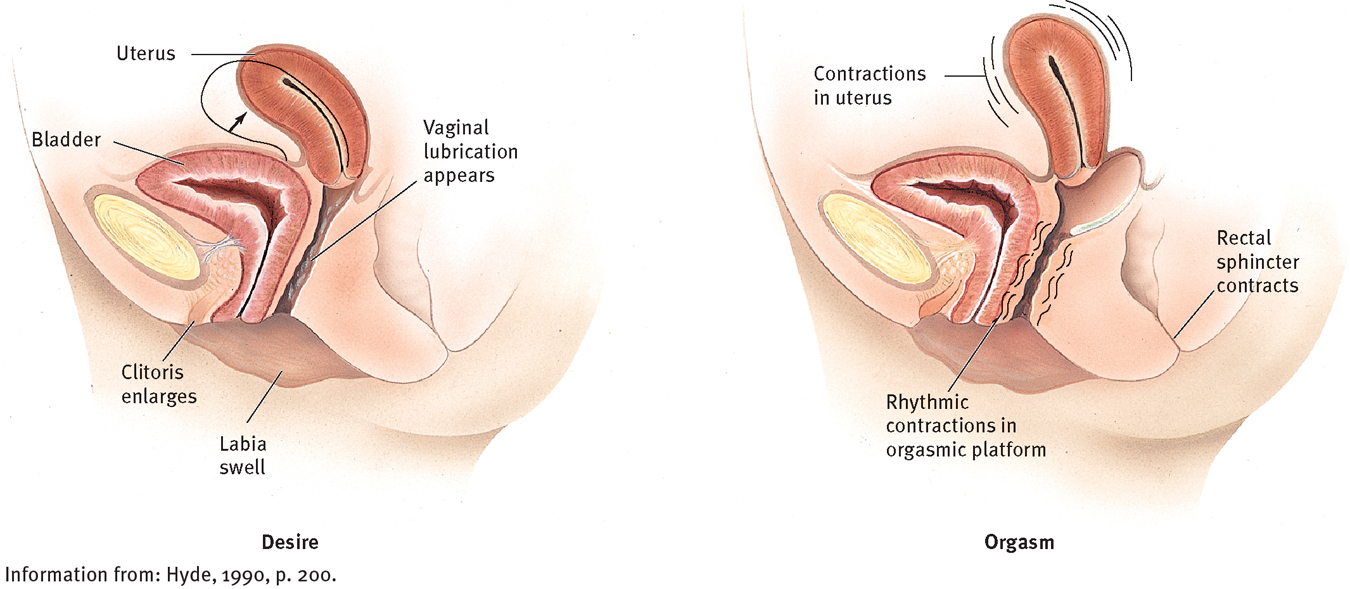

Normal female sexual anatomy

Changes in the female anatomy take place during the different phases of the sexual response cycle.

Recent investigations also have suggested that low sexual desire may be linked to excessive activity of the neurotransmitters serotonin and dopamine (Chan et al., 2011). In one study, for example, female rats were administered apomorphine, a drug known to increase dopamine activity in certain areas of the brain (Snoeren et al., 2011). These rats then avoided sexual contact with male rats.

Clinical practice and research have further indicated that sex drive can be lowered by certain pain medications, psychotropic drugs, and illegal drugs such as cocaine, marijuana, amphetamines, and heroin (Glina, Sharlip, & Hellstrom, 2013; Montejo et al., 2011). Low levels of alcohol may enhance the sex drive by lowering a person’s inhibitions, but high levels may reduce it (George et al., 2011; Hart et al., 2010).

Long-

Psychological Causes of Low Sexual DesireA general increase in anxiety, depression, or anger may reduce sexual desire in both men and women (Rubio-

Certain psychological disorders may also contribute to low sexual desire. Even a mild level of depression can interfere with sexual desire, and some people with obsessive-

Sociocultural Causes of Low Sexual DesireThe attitudes, fears, and psychological disorders that contribute to low sexual desire occur within a social context, and thus certain sociocultural factors have also been linked to disorders of sexual desire. Many people who have low sexual desire are feeling situational pressures—

Cultural standards can also set the stage for low sexual desire. Some men adopt our culture’s double standard and thus cannot feel sexual desire for a woman they love and respect (Maurice, 2007). More generally, because our society equates sexual attractiveness with youthfulness, many middle-

The trauma of sexual molestation or assault is especially likely to produce the fears, attitudes, and memories found in disorders of sexual desire. Some survivors of sexual abuse may feel repelled by sex, sometimes for years, even decades (Giraldi et al., 2013; Brotto et al., 2011; Zwickl & Merriman, 2011). In some cases, survivors may have vivid flashbacks of the assault during adult consensual sexual activity.

Disorders of Excitement

The excitement phase of the sexual response cycle is marked by changes in the pelvic region, general physical arousal, and increases in heart rate, muscle tension, blood pressure, and rate of breathing. In men, blood pools in the pelvis and leads to erection of the penis; in women, this phase produces swelling of the clitoris and labia, as well as lubrication of the vagina. As you read earlier, female sexual interest/arousal disorder may include dysfunction during the excitement phase. In addition, a male disorder—

excitement phase The phase of the sexual response cycle marked by changes in the pelvic region, general physical arousal, and increases in heart rate, muscle tension, blood pressure, and rate of breathing.

excitement phase The phase of the sexual response cycle marked by changes in the pelvic region, general physical arousal, and increases in heart rate, muscle tension, blood pressure, and rate of breathing.

Erectile DisorderMen with erectile disorder persistently fail to attain or maintain an erection during sexual activity (see Table 13-2). This problem occurs in as much as 25 percent of the male population, including Robert, the man whose difficulties opened this chapter (Martin et al., 2014; Christensen et al., 2011; Lewis et al., 2010). Carlos Domera also has erectile disorder:

Carlos Domera is a 30-

The couple separated a month ago by mutual agreement due to the tension that surrounded their sexual problem and their inability to feel comfortable with each other. Both professed love and concern for the other, but had serious doubts regarding their ability to resolve the sexual problem….

[Carlos] conformed to the stereotype of the “macho Latin lover,” believing that he “should always have erections easily and be able to make love at any time.” Since he couldn’t “perform” sexually, he felt humiliated and inadequate, and he dealt with this by avoiding not only sex, but any expression of affection for his wife.

[Phyllis] felt “he is not trying; perhaps he doesn’t love me, and I can’t live with no sex, no affection, and his bad moods.” She had requested the separation temporarily, and he readily agreed. However, they had recently been seeing each other twice a week….

During the evaluation he reported that the onset of his erectile difficulties was concurrent with a tense period in his business. After several “failures” to complete intercourse, he concluded he was “useless as a husband” and therefore a “total failure.” The anxiety of attempting lovemaking was too much for him to deal with.

He reluctantly admitted that he was occasionally able to masturbate alone to a full, firm erection and reach a satisfying orgasm. However, he felt ashamed and guilty about this, from both childhood masturbatory guilt and a feeling that he was “cheating” his wife. It was also noted that he had occasional firm erections upon awakening in the morning. Other than the antidepressant, the patient was taking no drugs, and he was not using much alcohol. There was no evidence of physical illness.

(Spitzer et al., 1983, pp. 105-

erectile disorder A dysfunction in which a man repeatedly fails to attain or maintain an erection during sexual activity.

erectile disorder A dysfunction in which a man repeatedly fails to attain or maintain an erection during sexual activity.

|

Erectile Disorder |

|

|---|---|

|

1. |

For at least 6 months, individual usually finds it very difficult to obtain an erection, maintain an erection, and/or achieve past levels of erectile rigidity during sex. |

|

2. |

Individual experiences significant distress. |

|

(Information from: APA, 2013.) |

|

Unlike Carlos, most men with an erectile disorder are over the age of 50, largely because so many cases are associated with ailments or diseases of older adults (Cameron et al., 2005). Around 7 percent of men who are under 40 years old also have the disorder; that number increases to as many as 40 percent of men in their sixties and 75 percent of those in their seventies and eighties (Lewis et al., 2010; Rosen, 2007). Moreover, according to surveys, half of all adult men experience erectile difficulty during intercourse at least some of the time. Most cases of erectile disorder result from an interaction of biological, psychological, and sociocultural processes (Berry & Berry, 2013; Rowland, 2012; Carvalho & Nobre, 2011).

Why do you think the clinical field has been slow to investigate possible cultural and racial differences in sexual behaviors?

BIOLOGICAL CAUSESThe same hormonal imbalances that can cause male hypoactive sexual desire disorder can also produce erectile disorder (Glina et al., 2013; Hyde, 2005). More commonly, however, vascular problems—

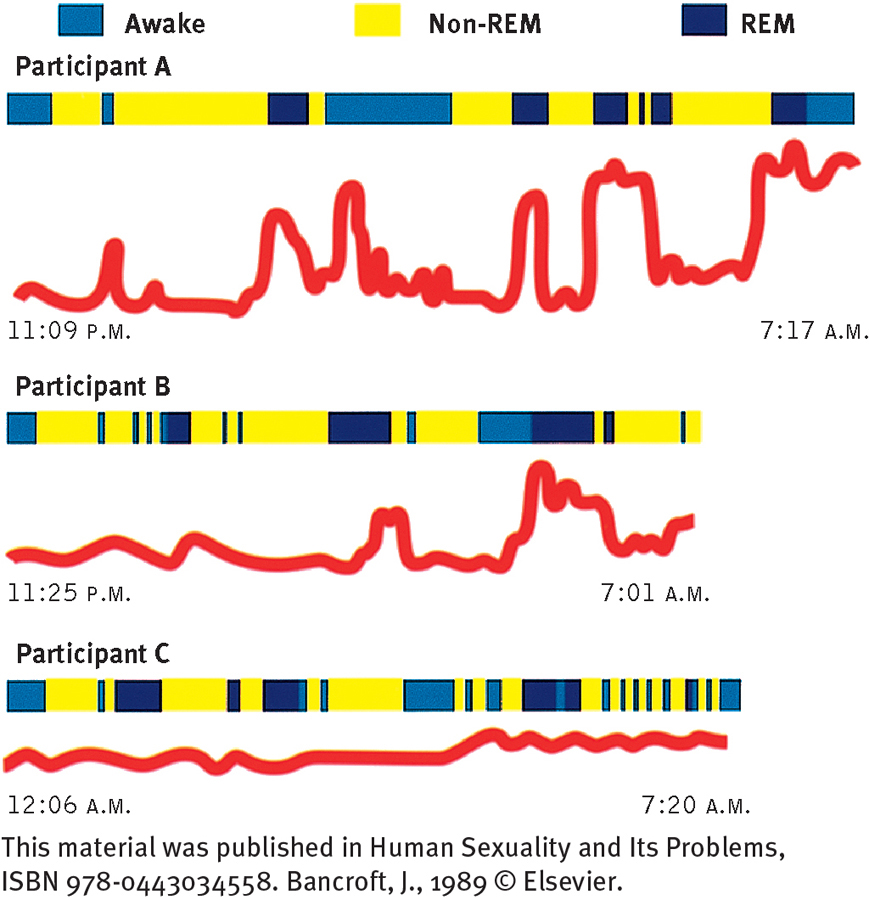

Medical procedures, including ultrasound recordings and blood tests, have been developed for diagnosing biological causes of erectile disorder. Measuring nocturnal penile tumescence (NPT), or erections during sleep, is particularly useful in assessing whether physical factors are responsible. Men typically have erections during rapid eye movement (REM) sleep, the phase of sleep in which dreaming takes place. A healthy man is likely to have two to five REM periods each night, and several penile erections as well (see Figure 13-3). Abnormal or absent nightly erections usually (but not always) indicate some physical basis for erectile failure. As a rough screening device, a patient may be instructed to fasten a simple “snap gauge” band around his penis before going to sleep and then check it the next morning. A broken band indicates that he has had an erection during the night. An unbroken band indicates that he did not have nighttime erections and suggests that his general erectile problem may have a physical basis. A newer version of this device further attaches the band to a computer, which provides precise measurements of erections throughout the night (Wincze et al., 2008). Such assessment devices are less likely to be used in clinical practice today than in past years. As you’ll see later in the chapter, Viagra and other drugs for erectile disorder are typically given to patients without much formal evaluation of their problem (Rosen, 2007).

nocturnal penile tumescence (NPT) Erection during sleep.

nocturnal penile tumescence (NPT) Erection during sleep.

Measurements of erections during sleep

Research participant A, a man without erectile problems, has normal erections during REM sleep. Participant B has erectile problems that seem to be at least partly psychogenic—

PSYCHOLOGICAL CAUSESAny of the psychological causes of male hypoactive sexual desire disorder can also interfere with arousal and lead to erectile disorder (Rowland, Georgoff, & Burnett, 2011). As many as 90 percent of all men with severe depression, for example, experience some degree of erectile dysfunction (Montejo et al., 2011; Stevenson & Elliott, 2007).

One well-

performance anxiety The fear of performing inadequately and a related tension experienced during sex.

performance anxiety The fear of performing inadequately and a related tension experienced during sex.

spectator role A state of mind that some people experience during sex, focusing on their sexual performance to such an extent that their performance and their enjoyment are reduced.

spectator role A state of mind that some people experience during sex, focusing on their sexual performance to such an extent that their performance and their enjoyment are reduced.

SOCIOCULTURAL CAUSESEach of the sociocultural factors that contribute to male hypoactive sexual desire disorder has also been tied to erectile disorder. Men who have lost their jobs and are under financial stress, for example, are more likely to develop erectile difficulties than other men (Štulhofer et al., 2013; Morokoff & Gilliland, 1993). Marital stress, too, has been tied to this dysfunction (Brenot, 2011; Wincze et al., 2008). Two relationship patterns in particular may contribute to it (Rosen, 2007; LoPiccolo, 2004, 1991). In one, a wife provides too little physical stimulation for her aging husband, who, because of normal aging changes, now requires more intense, direct, and lengthy physical stimulation of the penis in order to have an erection. In the second relationship pattern, a couple believes that only intercourse can give the wife an orgasm. This idea increases the pressure on the man to have an erection and makes him more vulnerable to erectile dysfunction. If the wife reaches orgasm manually or orally during their sexual encounter, his pressure to perform is reduced.

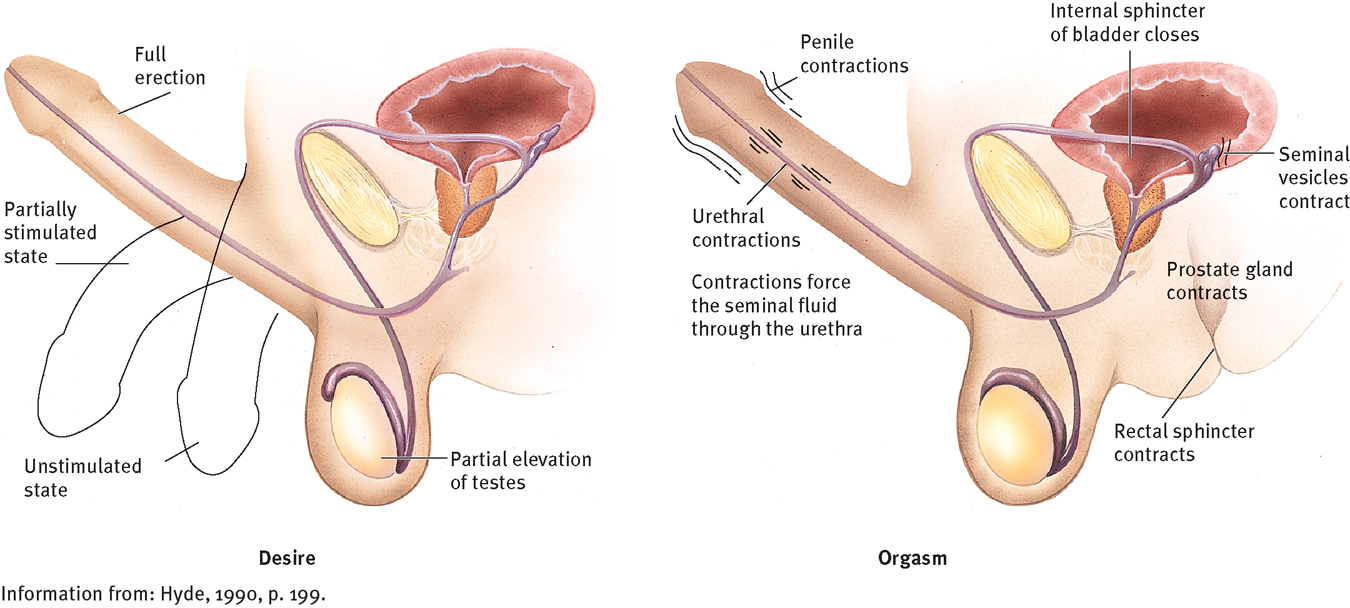

Disorders of Orgasm

During the orgasm phase of the sexual response cycle, a person’s sexual pleasure peaks and sexual tension is released as the muscles in the pelvic region contract, or draw together, rhythmically (see Figure 13-4 below). The man’s semen is ejaculated, and the outer third of the woman’s vaginal wall contracts. Dysfunctions of this phase of the sexual response cycle are early ejaculation and delayed ejaculation in men and female orgasmic disorder in women.

orgasm phase The phase of the sexual response cycle during which a person’s sexual pleasure peaks and sexual tension is released as muscles in the pelvic region contract rhythmically.

orgasm phase The phase of the sexual response cycle during which a person’s sexual pleasure peaks and sexual tension is released as muscles in the pelvic region contract rhythmically.

Premature EjaculationEduardo is typical of many men in his experience of premature ejaculation:

Eduardo, a 20-

A man suffering from premature ejaculation (also called early, or rapid, ejaculation) persistently reaches orgasm and ejaculates within 1 minute of beginning sexual activity with a partner and before he wishes to (see Table 13-3). As many as 30 percent of men worldwide ejaculate early at some time (Lewis et al., 2010; Jannini & Lenzi, 2005; Laumann et al., 2005, 1999, 1994). The typical duration of intercourse in our society has increased over the past several decades, which has caused more distress among men who ejaculate prematurely. Although many young men certainly contend with the dysfunction, research suggests that men of any age may suffer from it (Rowland, 2012; Althof, 2007).

|

Premature Ejaculation |

|

|---|---|

|

1. |

For at least 6 months, individual usually ejaculates within 1 minute of beginning sex with a partner and earlier than he wants to. |

|

2. |

Individual experiences significant distress. |

|

Delayed Ejaculation |

|

|

1. |

For at least 6 months, individual usually displays a significant delay, infrequency, or absence of ejaculation during sexual activity with a partner. |

|

2. |

Individual experiences significant distress. |

|

Female Orgasmic Disorder |

|

|

1. |

For at least 6 months, individual usually displays a significant delay, infrequency, or absence of orgasm, and/or is unable to achieve past orgasmic intensity. |

|

2. |

Individual experiences significant distress. |

|

(Information from: APA, 2013.) |

|

premature ejaculation A dysfunction in which a man persistently reaches orgasm and ejaculates within 1 minute of beginning sexual activity with a partner and before he wishes to. Also called early or rapid ejaculation.

premature ejaculation A dysfunction in which a man persistently reaches orgasm and ejaculates within 1 minute of beginning sexual activity with a partner and before he wishes to. Also called early or rapid ejaculation.

Psychological, particularly behavioral, explanations of premature ejaculation have received more research support than other kinds of explanations. The dysfunction is common, for example, among young, sexually inexperienced men such as Eduardo, who simply have not learned to slow down, control their arousal, and extend the pleasurable process of making love (Althof, 2007). In fact, young men often ejaculate prematurely during their first sexual encounter. With continued sexual experience, most men acquire more control over their sexual responses. Men of any age who have sex only occasionally are also prone to ejaculate early.

Clinicians have also suggested that premature ejaculation may be related to anxiety, hurried masturbation experiences during adolescence (in fear of being “caught” by parents), or poor recognition of one’s own sexual arousal (Althof, 2007; Westheimer & Lopater, 2005). However, these theories have only sometimes received clear research support.

There is a growing belief among many clinical theorists that biological factors may also play a key role in many cases of premature ejaculation. Three biological theories have emerged from the limited investigations done so far (Althof, 2007; Mirone et al., 2001; Waldinger et al., 1998). One theory states that some men are born with a genetic predisposition to develop this dysfunction. Indeed, one study found that 91 percent of a small sample of men suffering from early ejaculation had first-

Delayed EjaculationA man with delayed ejaculation (previously called male orgasmic disorder or inhibited male orgasm) persistently is unable to ejaculate or has very delayed ejaculations during sexual activity with a partner (see Table 13-3 again). Around 10 percent of men worldwide have this disorder (Lewis et al., 2010; Hartmann & Waldinger, 2007; Laumann et al., 2005, 1999). It is typically a source of great frustration and upset, as in the case of John:

John, a 38-

About 3 years prior to seeking counseling, after the birth of their only child, John found that he was losing his erection before he was able to ejaculate. His wife suggested different intercourse positions, but the harder he tried, the more difficulty he had in reaching orgasm. Because of his frustration, the couple began to avoid sex altogether. John experienced increasing performance anxiety with each successive failure, and an increasing sense of helplessness in the face of his problem.

(Rosen & Rosen, 1981, pp. 317-

delayed ejaculation A male dysfunction characterized by persistent inability to ejaculate or very delayed ejaculations during sexual activity with a partner.

delayed ejaculation A male dysfunction characterized by persistent inability to ejaculate or very delayed ejaculations during sexual activity with a partner.

Normal male sexual anatomy

Changes in the male anatomy occur during the different phases of the sexual response cycle.

A low testosterone level, certain neurological diseases, and some head or spinal cord injuries can interfere with ejaculation (Lewis et al., 2010; Stevenson & Elliott, 2007; McKenna, 2001). Substances that slow down the sympathetic nervous system (such as alcohol, some medications for high blood pressure, and certain psycho-

BETWEEN THE LINES

Drugs That Sometimes Interfere with Sexual Functioning

Alcohol, opioids, sedative-

Cocaine, amphetamines

Hallucinogens, marijuana

Antidepressants, antipsychotics, diuretics, amyl nitrate, hypertension medications

A leading psychological cause of delayed ejaculation appears to be performance anxiety and the spectator role, the cognitive-

Are there other problem areas in life that might also be explained by performance anxiety and the spectator role?

Female Orgasmic DisorderJanel and Isaac, married for 3 years, went for sex therapy because of her lack of orgasm.

Janel had never had an orgasm in any way, but because of Isaac’s concern, she had been faking orgasm during intercourse until recently. Finally she told him the truth, and they sought therapy together. Janel had been raised by a strictly religious family. She could not recall ever seeing her parents kiss or show physical affection for each other. She was severely punished on one occasion when her mother found her looking at her own genitals, at about age 7. Janel received no sex education from her parents, and when she began to menstruate, her mother told her only that this meant that she could become pregnant, so she mustn’t ever kiss a boy or let a boy touch her. Her mother restricted her dating severely, with repeated warnings that “boys only want one thing.” While her parents were rather critical and demanding of her (asking her why she got one B among otherwise straight A’s on her report card, for example), they were loving parents and their approval was very important to her.

Some theorists believe that the women’s movement has helped to enlighten clinical views of sexual disorders. How might this be so?

Women with female orgasmic disorder persistently fail to reach orgasm, have very low intensity orgasms, or have a very delayed orgasm (see Table 13-3 again). As many as 25 percent of women apparently have this problem to some degree—

female orgasmic disorder A dysfunction in which a woman persistently fails to reach orgasm, has very low intensity orgasms, or has very delayed orgasms.

female orgasmic disorder A dysfunction in which a woman persistently fails to reach orgasm, has very low intensity orgasms, or has very delayed orgasms.

Most clinicians agree that orgasm during intercourse is not mandatory for normal sexual functioning (Meana, 2012; Wincze et al., 2008). Many women instead reach orgasm with their partners by direct stimulation of the clitoris. Although early psychoanalytic theory considered a lack of orgasm during intercourse to be pathological, evidence suggests that women who rely on stimulation of the clitoris for orgasm are entirely normal and healthy (Laan, Rellini, & Barnes, 2013; Heiman, 2007; LoPiccolo, 2002, 1995).

Biological, psychological, and sociocultural factors may combine to produce female orgasmic disorder (Berry & Berry, 2013; Jiann, Su, & Tsai, 2013; Heiman, 2007). Because arousal plays a key role in orgasms, arousal difficulties often are featured prominently in explanations of female orgasmic disorder (Laan et al., 2013).

BIOLOGICAL CAUSESA variety of physiological conditions can affect a woman’s orgasm. Diabetes can damage the nervous system in ways that interfere with arousal, lubrication of the vagina, and orgasm. Lack of orgasm has sometimes been linked to multiple sclerosis and other neurological diseases, to the same drugs and medications that may interfere with ejaculation in men, and to changes, often postmenopausal, in skin sensitivity and structure of the clitoris, vaginal walls, or the labia—

PSYCHOLOGICAL CAUSESThe psychological causes of female sexual interest/arousal disorder, including depression, may also lead to female orgasmic disorder (Laan et al., 2013; Kashdan et al., 2011; Kim et al., 2011). In addition, as both psychodynamic and cognitive theorists might predict, memories of childhood traumas and relationships have sometimes been associated with orgasm problems (Laan et al., 2013). In one large study, memories of an unhappy childhood or loss of a parent during childhood were tied to lack of orgasm in adulthood (Raboch & Raboch, 1992). In other studies, childhood memories of a dependable father, a positive relationship with one’s mother, affection between the parents, the mother’s positive personality, and the mother’s expression of positive emotions were all predictors of positive orgasm outcomes (Heiman, 2007; Heiman et al., 1986).

SOCIOCULTURAL CAUSESFor years many clinicians have believed that female orgasmic problems may result from society’s recurrent message to women that they should repress and deny their sexuality, a message that has often led to “less permissive” sexual attitudes and behavior among women than among men. In fact, many women with both arousal and orgasmic difficulties report that they had an overly strict religious upbringing, were punished for childhood masturbation, received no preparation for the onset of menstruation, were restricted in their dating as teenagers, and were told that “nice girls don’t” (Laan et al., 2013; LoPiccolo & Van Male, 2000).

A sexually restrictive history, however, is just as common among women who function well during sexual activity (LoPiccolo, 2002, 1997). In addition, cultural messages about female sexuality have been more positive in recent years, while the rate of arousal and orgasmic problems remains the same for women. Why, then, do some women and not others develop such problems? Researchers suggest that unusually stressful events, traumas, or relationships may help produce the fears, memories, and attitudes that often characterize these sexual problems (Meana, 2012; Westheimer & Lopater, 2005). For example, many women molested as children or raped as adults have female orgasmic disorder (Hall, 2007; Heiman, 2007).

Research has also related orgasmic behavior to certain qualities in a woman’s intimate relationships (Laan et al., 2013; Brenot, 2011; Heiman et al., 1986). Studies have found, for example, that the likelihood of reaching orgasm may be tied to how much emotional involvement a woman had during her first experience of intercourse and how long that relationship lasted, the pleasure the woman felt during the experience, her current attraction to her partner’s body, and her marital happiness. Interestingly, the same studies have found that orgasmic women more often have erotic fantasies during sex with their current partner than do nonorgasmic women.

Disorders of Sexual Pain

Certain sexual dysfunctions are characterized by enormous physical discomfort during intercourse, a difficulty that does not fit neatly into a specific part of the sexual response cycle. Women have such dysfunctions, collectively called genito-pelvic pain/penetration disorder, much more often than men do (APA, 2013).

genito-pelvic pain/penetration disorder A sexual dysfunction characterized by significant physical discomfort during intercourse.

genito-pelvic pain/penetration disorder A sexual dysfunction characterized by significant physical discomfort during intercourse.

For some women with genito-

|

Genito- |

|

|---|---|

|

1. |

For at least 6 months, individual repeatedly experiences at least one of the following problems: • Difficulty having vaginal penetration during intercourse • Significant vaginal or pelvic pain when trying to have intercourse or penetration • Significant fear that vaginal penetration will cause vaginal or pelvic pain • Significant tensing of the pelvic muscles during vaginal penetration. |

|

2. |

Individual experiences significant distress from this. |

|

(Information from: APA, 2013.) |

|

Most clinicians agree with the cognitive-

Alternatively, women may have this form of genito-

Other women with genito-

This form of genito-

BETWEEN THE LINES

Nightly Visits

People can sometimes have an orgasm during sleep. Ancient Babylonians said that such nocturnal orgasms were caused by a “maid of the night” who visited men in their sleep and a “little night man” who visited women (Kahn & Fawcett, 1993).

Although psychological factors (for instance, heightened anxiety or overattentiveness to one’s body) or relationship problems may contribute to dyspareunia (Granot et al., 2011), psychosocial factors alone are rarely responsible for it (Dewitte, Van Lankveld, & Crombez, 2011). In cases that are truly psychogenic, the woman may in fact be suffering from female sexual interest/arousal disorder. That is, penetration into an unaroused, unlubricated vagina is painful (Fugl-