13.2 Treatments for Sexual Dysfunctions

The last 40 years have brought major changes in the treatment of sexual dysfunctions. For the first half of the twentieth century, the leading approach was long-

BETWEEN THE LINES

“Just a Second”

According to recent surveys, 1 in 10 respondents admit to using their cell phone during sex (Archer, 2013).

In the 1950s and 1960s, behavioral therapists offered new treatments for sexual dysfunctions. Usually they tried to reduce the fears that they believed were causing the dysfunctions. They did so through such procedures as relaxation training and systematic desensitization (Lazarus, 1965; Wolpe, 1958). These approaches had some success, but they failed to work in cases where the key problems included misinformation, negative attitudes, and lack of effective sexual techniques (LoPiccolo, 2002, 1995).

Sex is one of the topics most commonly searched on the Internet. Why might it be such a popular search topic?

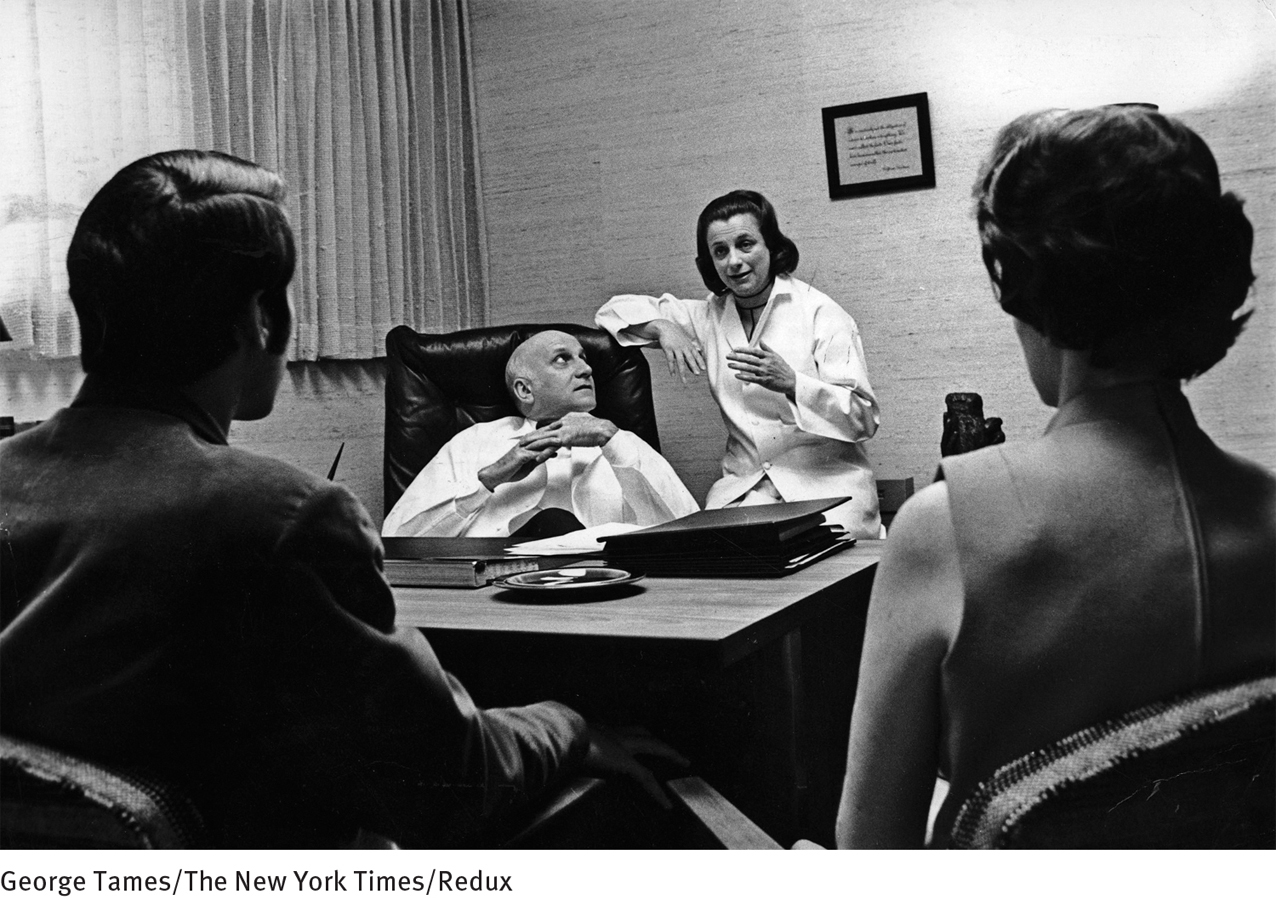

A revolution in the treatment of sexual dysfunctions took place with the publication of William Masters and Virginia Johnson’s landmark book Human Sexual Inadequacy in 1970. The sex therapy program they introduced has evolved into a complex approach, which now includes interventions from the various models, particularly cognitive-

What Are the General Features of Sex Therapy?

Modern sex therapy is short-

At the end of the evaluation session the psychiatrist reassured the couple that Mr. Domera had a “reversible psychological” sexual problem that was due to several factors, including his depression, but also more currently his anxiety and embarrassment, his high standards, and some cultural and relationship difficulties that made communication awkward and relaxation nearly impossible. The couple was advised that a brief trial of therapy, focused directly on the sexual problem, would very likely produce significant improvement within ten to fourteen sessions. They were assured that the problem was almost certainly not physical in origin, but rather psychogenic, and that therefore the prognosis was excellent.

Mr. Domera was shocked and skeptical, but the couple agreed to commence the therapy on a weekly basis, and they were given a typical first “assignment” to do at home: a caressing massage exercise to try together with specific instructions not to attempt genital stimulation or intercourse at all, even if an erection might occur.

Not surprisingly, during the second session Mr. Domera reported with a cautious smile that they had “cheated” and had had intercourse “against the rules.” This was their first successful intercourse in more than a year. Their success and happiness were acknowledged by the therapist, but they were cautioned strongly that rapid initial improvement often occurs, only to be followed by increased performance anxiety in subsequent weeks and a return of the initial problem. They were humorously chastised and encouraged to try again to have sexual contact involving caressing and non-

During the second and fourth weeks [Carlos] did not achieve erections during the love play, and the therapy sessions dealt with helping him to accept himself with or without erections and to learn to enjoy sensual contact without intercourse. His wife helped him to believe genuinely that he could please her with manual or oral stimulation and that, although she enjoyed intercourse, she enjoyed these other stimulations as much, as long as he was relaxed.

[Carlos] struggled with his cultural image of what a “man” does, but he had to admit that his wife seemed pleased and that he, too, was enjoying the noninter-

By the fifth week the patient was attempting intercourse successfully with relaxed confidence, and by the ninth session he was responding regularly with erections. If they both agreed, they would either have intercourse or choose another sexual technique to achieve orgasm. Treatment was terminated after ten sessions.

(Spitzer et al., 1983, pp. 106–

As Carlos Domera’s treatment indicates, modern sex therapy includes a variety of principles and techniques. The following ones are used in almost all cases, regardless of the dysfunction:

Assessing and conceptualizing the problem. Patients are initially given a medical examination and are interviewed concerning their “sex history.” The therapist’s focus during the interview is on gathering information about past life events and, in particular, current factors that are contributing to the dysfunction (Althof et al., 2013: Berry & Berry, 2013; Meana, 2012). Sometimes proper assessment requires a team of specialists, perhaps including a psychologist, urologist, and neurologist.

Mutual responsibility. Therapists stress the principle of mutual responsibility. Both partners in the relationship share the sexual problem, regardless of who has the actual dysfunction, so treatment is likely to be more successful when both are in therapy (Laan et al., 2013; McCarthy & McCarthy, 2012; Brenot, 2011).

Education about sexuality. Many patients who suffer from sexual dysfunctions know very little about the physiology and techniques of sexual activity (McMahon et al., 2013; Rowland, 2012; Hinchliff & Gott, 2011). Thus sex therapists may discuss these topics and offer educational materials, including instructional books, videos, and Internet sites.

Emotion identification. Sex therapists help patients identify and express upsetting emotions tied to past events that may keep interfering with sexual arousal and enjoyment (Kleinplatz, 2010).

Attitude change. Following a cardinal principle of cognitive therapy, sex therapists help patients examine and change any beliefs about sexuality that are preventing sexual arousal and pleasure (McCarthy & McCarthy, 2012; Hall, 2010; Wincze et al., 2008). Some of these mistaken beliefs are widely shared in our society and can result from past traumatic events, family attitudes, or cultural ideas.

Elimination of performance anxiety and the spectator role. Therapists often teach couples sensate focus, or nondemand pleasuring, a series of sensual tasks, sometimes called “petting” exercises, in which the partners focus on the sexual pleasure that can be achieved by exploring and caressing each other’s body at home, without demands to have intercourse or reach orgasm—

demands that may be interfering with arousal. Couples are told at first to refrain from intercourse at home and to restrict their sexual activity to kissing, hugging, and sensual massage of various parts of the body, but not of the breasts or genitals. Over time, they learn how to give and receive greater sexual pleasure and they build back up to the activity of sexual intercourse (Rowland, 2012). Page 441 "When I touch him he rolls into a ball."

"When I touch him he rolls into a ball."Increasing sexual and general communication skills. Couples are taught to use their sensate-

focus skills and apply new sexual techniques and positions at home. They may, for example, try sexual positions in which the person being caressed can guide the other’s hands and control the speed, pressure, and location of sexual contact (Heiman, 2007). Couples are also taught to give instructions to each other in a nonthreatening, informative manner (“It feels better over here, with a little less pressure”), rather than a threatening uninformative manner (“The way you’re touching me doesn’t turn me on”). Moreover, couples are often given broader training in how best to communicate with each other (Brenot, 2011; Wincze et al., 2008). Changing destructive lifestyles and marital interactions. A therapist may encourage a couple to change their lifestyle or take other steps to improve a situation that is having a destructive effect on their relationship—

to distance themselves from interfering in- laws, for example, or to change a job that is too demanding. Similarly, if the couple’s general relationship is marked by conflict, the therapist will try to help them improve it, often before work on the sexual problems per se begins (Brenot, 2011; Rosen, 2007). Addressing physical and medical factors. Systematic increases in physical activity have proved helpful for persons with various kinds of sexual dysfunctions (Lewis et al., 2010). In addition, when sexual dysfunctions are caused by a medical problem, such as disease, injury, medication, or substance abuse, therapists try to address that problem (Korda et al., 2010; Ashton, 2007). If antidepressant medications are causing erectile disorder, for example, the clinician may suggest lowering the dosage of the medication, changing the time of day when the drug is taken, or turning to a different antidepressant.

What Techniques Are Used to Treat Particular Dysfunctions?

In addition to the general components of sex therapy, specific techniques can help in each of the sexual dysfunctions.

Disorders of DesireMale hypoactive sexual desire disorder and female sexual interest/arousal disorder are among the most difficult dysfunctions to treat because of the many issues that may feed into them (Leiblum, 2010). Thus therapists typically use a combination of techniques. In a technique called affectual awareness, patients visualize sexual scenes in order to discover any feelings of anxiety, vulnerability, and other negative emotions they may have concerning sex (McCarthy & McCarthy, 2012; Kleinplatz, 2010). In another technique, patients receive cognitive self-

BETWEEN THE LINES

In Their Words

“Some nights he said that he was tired, and some nights she said that she wanted to read, and other nights no one said anything.”

Joan Didion, Play It as It Lays

Therapists may also use behavioral approaches to help heighten a patient’s sex drive. They may instruct clients to keep a “desire diary” in which they record sexual thoughts and feelings, to read books and view films with erotic content, and to fantasize about sex. They also may encourage pleasurable shared activities such as dancing and walking together (Rubio-

BETWEEN THE LINES

Favorite Part of the Sexual Cycle

In some studies, the majority of female participants from sexually healthy and generally positive marriages reported that foreplay is the most satisfying component of sexual activity with their partner (Basson, 2007; Hurlbert et al., 1993).

Finally, biological interventions, such as hormone treatments, have been used, particularly for women whose problems arose after removal of their ovaries or later in life. These interventions have received some research support (Rubio-

Erectile DisorderTreatments for erectile disorder focus on reducing a man’s performance anxiety, increasing his stimulation, or both, using a range of behavioral, cognitive, and relationship interventions (Rowland, 2012; Carroll, 2011; Segraves & Althof, 2002). In one technique, the couple may be instructed to try the tease technique during sensate-

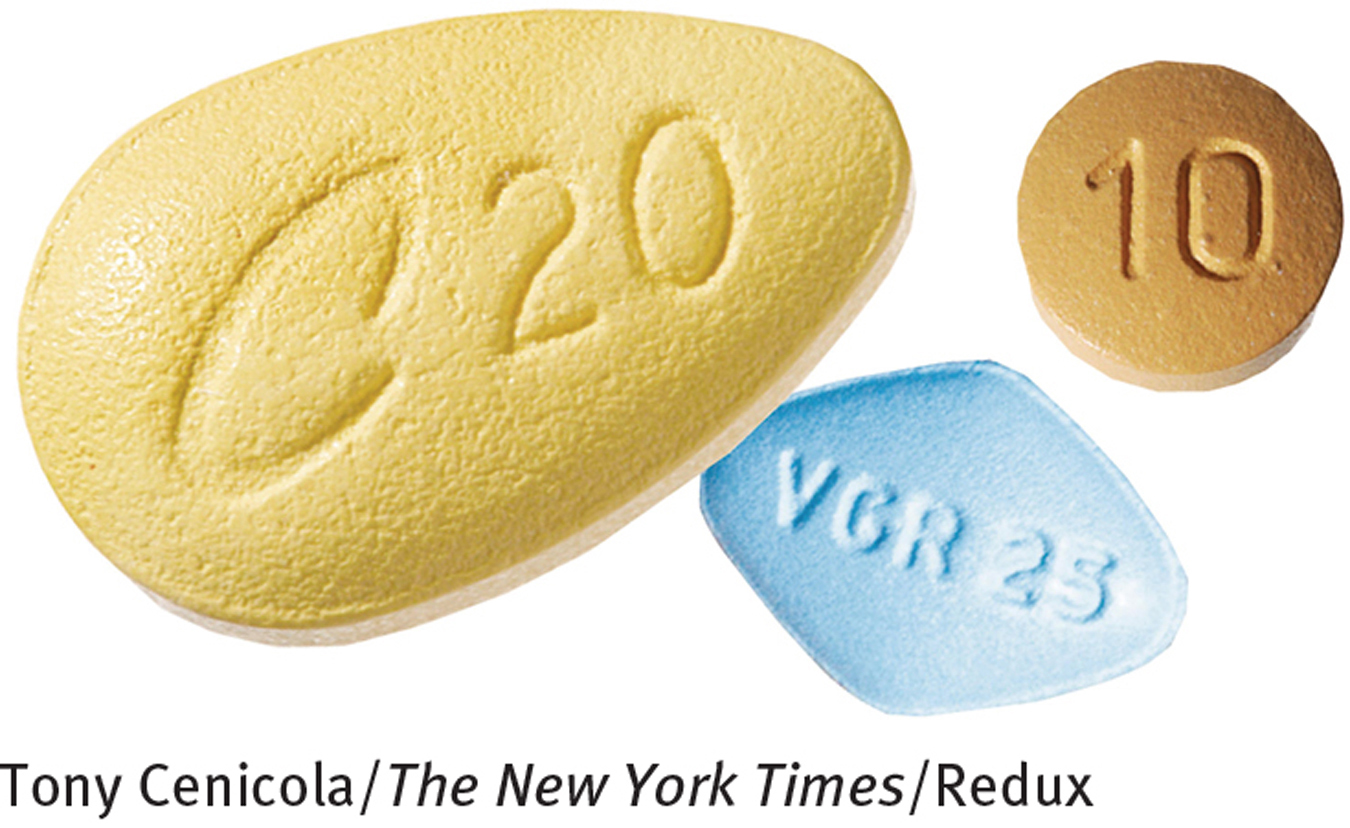

Biological approaches gained great momentum with the development in 1998 of sildenafil (trade name Viagra) (Rosen, 2007). This drug increases blood flow to the penis within one hour of ingestion; the increased blood flow enables the user to attain an erection during sexual activity (see PsychWatch below). In general, sildenafil appears to be safe; however, it may not be so for men with certain coronary heart diseases and cardiovascular diseases, particularly those who are taking nitro glycerin and other heart medications (Stevenson & Elliott, 2007). Soon after Viagra emerged, two other erectile dysfunction drugs were also approved—

Prior to the development of Viagra, Cialis, and Levitra, a range of other medical procedures were developed for erectile disorder. These procedures are now viewed as “second line”—often costly—

PsychWatch

Sexism, Viagra, and the Pill

Many of us believe that we live in an enlightened world, where sexism is declining and where health care and benefits are available to men and women in equal measure. Periodically, however, such illusions are shattered (Goldstein, 2014). The responses of government agencies and insurance companies to the discovery and marketing of Viagra in 1998 may be a case in point.

Consider, first, the nation of Japan. In early 1999, just 6 months after it was introduced in the United States, Viagra was approved for use among men in Japan (Goldstein, 2014; Martin, 2000). In contrast, low-

Has the United States been able to avoid such an apparent double standard in its health care system? Not really. Before Viagra was introduced, insurance companies were not required to reimburse women for the cost of prescription contraceptives. As a result, women had to pay 68 percent more out-

In contrast, when Viagra was introduced in 1998, many insurance companies readily agreed to cover it, and many states included Viagra as part of Medicaid coverage. As the public outcry grew over the contrast between coverage of Viagra for men and lack of coverage of oral contraceptives for women, laws across the country finally began to change. By the end of 1998, nine states required prescription contraceptive coverage (Hayden, 1998). Today 28 states require such coverage by private insurance companies (Guttmacher, 2011). The Affordable Care Act—

Premature EjaculationEarly ejaculation has been treated successfully for years by behavioral procedures (McMahon et al., 2013; Rowland, 2012; Masters & Johnson, 1970). In one such approach, the stop-

Some clinicians treat premature ejaculation with SSRIs, the serotonin-

Delayed EjaculationTherapies for delayed ejaculation include techniques to reduce performance anxiety and increase stimulation (Rowland, 2012; Hartmann & Waldinger, 2007; LoPiccolo, 2004). In one of many such techniques, a man may be instructed to masturbate to orgasm in the presence of his partner or to masturbate just short of orgasm before inserting his penis for intercourse (Marshall, 1997). This increases the likelihood that he will ejaculate during intercourse. He then is instructed to insert his penis at ever earlier stages of masturbation.

When delayed ejaculation is caused by physical factors such as neurological damage or injury, treatment may include a drug to increase arousal of the sympathetic nervous system (Stevenson & Elliott, 2007). However, few studies have systematically tested the effectiveness of such treatments (Hartmann & Waldinger, 2007).

Female Orgasmic DisorderSpecific treatments for female orgasmic disorder include cognitive-

In directed masturbation training, a woman is taught step by step how to masturbate effectively and eventually to reach orgasm during sexual interactions. The training includes the use of diagrams and reading material, private self-

directed masturbation training A sex therapy approach that teaches women with female arousal or orgasmic problems how to masturbate effectively and eventually to reach orgasm during sexual interactions.

directed masturbation training A sex therapy approach that teaches women with female arousal or orgasmic problems how to masturbate effectively and eventually to reach orgasm during sexual interactions.

As you read earlier, a lack of orgasm during intercourse is not necessarily a sexual dysfunction, provided the woman enjoys intercourse and can reach orgasm through caressing, either by her partner or by herself. For this reason some therapists believe that the wisest course is simply to educate women whose only concern is lack of orgasm during intercourse, informing them that they are quite normal.

Genito-

BETWEEN THE LINES

Sexual Census

The World Health Organization estimates that around 115 million acts of sexual intercourse occur each day.

Different approaches are used to treat the other form of genito-

What Are the Current Trends in Sex Therapy?

Sex therapists have now moved well beyond the approach first developed by Masters and Johnson. For example, today’s sex therapists regularly treat partners who are living together but not married. They also treat sexual dysfunctions that arise from psychological disorders such as depression, mania, schizophrenia, and certain personality disorders (Leiblum, 2010, 2007; Bach et al., 2001). In addition, sex therapists no longer screen out clients with severe marital discord, the elderly, the medically ill, the physically handicapped, gay clients, or individuals who have no long-

Many sex therapists have expressed concern about the sharp increase in the use of drugs and other medical interventions for sexual dysfunctions, particularly for the disorders characterized by low sexual desire and erectile disorder. Their concern is that therapists will increasingly choose the biological interventions rather than integrating biological, psychological, and sociocultural interventions. In fact, a narrow approach of any kind probably cannot fully address the complex factors that cause most sexual problems (Berry & Berry, 2013; Meana, 2012). It took sex therapists years to recognize the considerable advantages of an integrated approach to sexual dysfunctions. The development of new medical interventions should not lead to its abandonment.