13.4 Gender Dysphoria

As children and adults, most people feel like and identify themselves as males or females—a feeling and identity that is consistent with their assigned gender, the gender to which they are born. But society has come to appreciate that many people do not experience such gender clarity. Instead, they have transgender experiences—a sense that their actual gender identity is different from their assigned gender or a sense that it lies outside the usual male versus female categories. It is estimated that 1.5 million people in the United States are transgender—0.5% of the population (Steinmetz, 2014). The prevalence in other countries is about the same (Kuyper & Wijsen, 2014). Many transgender people come to terms with their gender inconsistencies, but others experience extreme unhappiness with their assigned gender and may seek treatment for their problem. DSM-5 categorizes these people as having gender dysphoria, a disorder in which people persistently feel that a vast mistake has been made—they have been born to the wrong sex—and have clinically significant distress or impairment with this gender mismatch (see Table 13-6).

Table : table: 13-6Dx Checklist

Gender Dysphoria in Adolescents and Adults |

|

|

For 6 months or more, individual’s gender-related feelings and/or behaviors is at odds with those of his or her assigned gender, as indicated by two or more of the following symptoms: • Gender-related feelings and/or behaviors clearly contradict the individual’s primary or secondary sex characteristics • Powerful wish to eliminate one’s sex characteristics • Yearning for the sex characteristics of another gender • Powerful wish to be a member of another gender • Yearning to be treated as a member of another gender • Firm belief that one’s feelings and reactions are those that characterize another gender. |

|

|

Individual experiences significant distress or impairment. |

(Information from: APA, 2013.) |

gender dysphoria A disorder in which a person persistently feels clinically significant distress or impairment due to his or her assigned gender and strongly wishes to be a member of another gender.

gender dysphoria A disorder in which a person persistently feels clinically significant distress or impairment due to his or her assigned gender and strongly wishes to be a member of another gender.

The DSM-5 categorization of gender dysphoria is controversial (Sennott, 2011; Dannecker, 2010). Many argue that since transgender experiences reflect alternative—not pathological—ways of experiencing one’s gender identity, they should never be considered a psychological disorder, even when they bring significant unhappiness. At the other end of the spectrum, many argue that transgender experiences are in fact a medical problem that may produce personal unhappiness for some of the people with these experiences. According to this position, gender dysphoria should not be categorized as a psychological disorder, just as kidney disease and cancer, medical conditions that may also produce unhappiness, are not categorized as psychological disorders. Although one of these views may eventually prove to be an appropriate perspective, this chapter largely will follow DSM-5’s position that (1) a transgender orientation is more than a variant lifestyle if it is accompanied by significant distress or impairment, and (2) a transgender orientation is far from a clearly defined medical problem. We will also examine what clinical theorists believe they know about gender dysphoria.

Page 457

A delicate matter A 5-year-old boy (left), who identifies and dresses as a girl and asks to be called “she,” plays with a female friend. Sensitive to the gender identity rights movement and to the special needs of children with gender dysphoria, a growing number of parents, educators, and clinicians are now supportive of children like this boy.

People with gender dysphoria typically would like to get rid of their primary and secondary sex characteristics—many of them find their own genitals repugnant—and acquire the characteristics of another sex (APA, 2013). Men with this disorder (i.e., “male-assigned people”) outnumber women (“female-assigned people”) by around 2 to 1. The individuals feel anxiety or depression and may have thoughts of suicide (Judge et al., 2014; Steinmetz, 2014). Such reactions may be related to the confusion and pain brought on by the disorder itself, or they may be tied to the prejudice typically faced by people who are transgender. According to an extensive survey across the United States, for example, 80 to 90 percent of transgender people have been harassed at school or work; 50 percent have been fired from a job, not hired, or not promoted; and 20 percent have been denied a place to live (Steinmetz, 2014). Studies also suggest that some people with gender dysphoria manifest a personality disorder (Singh et al., 2011). Today the term gender dysphoria has replaced the old term transsexualism, although the word “transsexual” is still sometimes used to describe those who desire and seek full gender change, often by surgery (APA, 2013).

Sometimes gender dysphoria emerges in children (Milrod, 2014; Nicholson & McGuinness, 2014; APA, 2013). Like adults with this disorder, the children feel uncomfortable about their assigned gender and yearn to be members of another gender. This childhood pattern usually disappears by adolescence or adulthood, but in some cases it develops into adolescent and adult forms of gender dysphoria (Cohen-Kettenis, 2001). Thus adults with this disorder may have had a childhood form of gender dysphoria, but most children with the childhood form do not become adults with the disorder. Surveys of mothers indicate that about 1.5 percent of young boys wish to be a girl, and 3.5 percent of young girls wish to be a boy (Carroll, 2007; Zucker & Bradley, 1995), yet considerably less than 1 percent of adults manifest gender dysphoria (Zucker, 2010). This age shift in the prevalence of gender dysphoria is, in part, why leading experts on the disorder strongly recommend against any form of irreversible physical treatment for this pattern until people reach adulthood, a recommendation upheld in the World Professional Association for Transgender Health Standards of Care (Milrod, 2014; HBIGDA, 2001). Nevertheless, some surgeons continue to perform such procedures for younger patients.

Explanations of Gender Dysphoria

Many clinicians suspect that biological factors—perhaps genetic or prenatal—play a key role in gender dysphoria (Rametti et al., 2011; Nawata et al., 2010). Consistent with a genetic explanation, the disorder does sometimes run in families. Research indicates, for example, that people whose siblings have gender dysphoria are more likely to have the same disorder than are people without such siblings (Gómez-Gil et al., 2010). Indeed, one study of 23 pairs of identical twins found that when one of the twins had gender dysphoria, the other twin had it as well in 9 of the pairs (Heylens et al., 2012).

Biological investigators have recently detected differences between the brains of control participants and participants with gender dysphoria. One study found, for example, that those with the disorder had heightened blood flow in the insula and reduced blood flow in the anterior cingulate cortex (Nawata et al., 2010). These brain areas are known to play roles in human sexuality and consciousness.

A biological study that was conducted around 20 years ago continues to receive considerable attention (Zhou et al., 1997, 1995). Dutch investigators autopsied the brains of six people who had changed their sex from male to female. They found that a cluster of cells in the hypothalamus called the bed nucleus of stria terminalis (BST) was only half as large in these people as it was in a control group of nontransgender men. Usually, a woman’s BST is much smaller than a man’s, so in effect the male-assigned people with gender dysphoria were found to have a female-sized BST. Scientists do not know for certain what the BST does in humans, but they know that it helps regulate sexual behavior in male rats. Thus it may be that male-assigned people who develop gender dysphoria have a key biological difference that leaves them very uncomfortable with their assigned sex characteristics.

Page 458

Treatments for Gender Dysphoria

In order to more effectively assess and treat those with gender dysphoria, clinical theorists have tried to distinguish the most common patterns of the disorder encountered in clinical practice.

Client Patterns of Gender DysphoriaRichard Carroll (2007), a leading theorist on gender dysphoria, has described the three patterns of gender dysphoria for which people most commonly seek treatment: (1) female-to-male gender dysphoria, (2) male-to-female gender dysphoria: androphilic type, and (3) male-to-female gender dysphoria: autogynephilic type.

FEMALE-TO-MALE GENDER DYSPHORIAPeople with a female-to-male gender dysphoria pattern are born female but appear or behave in a stereotypically masculine manner from early on—often as young as 3 years of age or younger. As children, they always play rough games or sports, prefer the company of boys, hate “girlish” clothes, and state their wish to be male. As adolescents, they become disgusted by the physical changes of puberty and are sexually attracted to females. However, lesbian relationships do not feel like a satisfactory solution to them because they want other women to be attracted to them as males, not as females.

MALE-TO-FEMALE GENDER DYSPHORIA: ANDROPHILIC TYPEPeople with an androphilic type of male-to-female gender dysphoria are born male but appear or behave in a stereotypically female manner from birth. As children, they are viewed as effeminate, pretty, and gentle; avoid rough games; and hate to dress in boys’ clothing. As adolescents, they become sexually attracted to males, and they often come out as gay and develop gay relationships (the term “androphilic” means attracted to males). But by adulthood, it often becomes clear to them that such gay relationships do not truly address their gender dysphoric feelings because they want to be with heterosexual men who are attracted to them as women.

Lea T. Transgender model Lea T. emerged in 2010 as the face of Givenchy, the famous French fashion brand. Born male, the Brazilian model has become a leading female figure in runway fashion shows and magazines, including Vogue Paris, Cover magazine, and Love magazine. In 2012 she underwent sexual reassignment surgery.

MALE-TO-FEMALE GENDER DYSPHORIA: AUTOGYNEPHILIC TYPEPeople with an autogynephilic type of male-to-female gender dysphoria are not sexually attracted to males; rather, they are attracted to the idea of themselves being female (the term “autogynephilic” means attracted to oneself as a female). Like males with the paraphilic disorder transvestic disorder (see pages 449–450), persons with this form of gender dysphoria behave in a stereotypically masculine manner as children, start to enjoy dressing in female clothing during childhood, and after puberty become sexually aroused when they cross-dress. Also, like males with transvestic disorder, they are attracted to females during and beyond adolescence. However, unlike people with transvestic disorder, these persons have desires of becoming female that become increasingly intense and overwhelming during adulthood.

In short, cross-dressing is characteristic of both men with transvestic disorder (the paraphilic disorder) and people with this type of male-to-female gender dysphoria (Zucker et al., 2012). But the former cross-dress strictly to become sexually aroused, whereas the latter develop much deeper reasons for cross-dressing, reasons of gender identity.

Page 459

Types of Treatment for Gender DysphoriaMany adults with gender dysphoria receive psychotherapy (Affatati et al., 2004), but a large number of them further seek to address their concerns through biological interventions (see MediaSpeak below). For example, many transgender adults change their sexual characteristics by means of hormone treatments (Wierckx et al., 2014; Traish & Gooren, 2010). Physicians prescribe the female sex hormone estrogen for male-assigned patients, causing breast development, loss of body and facial hair, and changes in body fat distribution. Some such patients also go to speech therapy, raising their tenor voice to alto through training, and some have facial feminization surgery (Capitan et al., 2014; Steinmetz, 2014). In contrast, treatments with the male sex hormone testosterone are given to female-assigned patients with gender dysphoria, resulting in a deeper voice, increased muscle mass, and changes in facial and body hair.

BETWEEN THE LINES

|

|

Percentage of Americans who say they have a close friend or family member who is transgender. |

|

|

Percentage of Americans who say they have a close friend or family member who is gay. |

(Information from Steinmetz, 2014) |

These approaches enable many persons with the disorder to lead a fulfilling life in the gender that fits them. For others, however, this is not enough, and they seek out one of the most controversial practices in medicine: sexual reassignment, or sex-change surgery (Judge et al., 2014; Andreasen & Black, 2006). This surgery, which is usually preceded by 1 to 2 years of hormone therapy, involves, for male-assigned persons, partial removal of the penis and restructuring of its remaining parts into a clitoris and vagina, a procedure called vaginoplasty. In addition, some individuals undergo face-changing plastic surgery. For female-assigned persons, surgery may include bilateral mastectomy and hysterectomy (Ott et al., 2010). The procedure for creating a functioning penis, called phalloplasty, is performed in some cases, but it is not perfected. Alternatively, doctors have developed a silicone prosthesis that can give patients the appearance of having male genitals. One review calculates that 1 of every 3,100 persons in the United States has had or will have sex-change surgery during their lifetime (Horton, 2008). For female-assigned persons, the incidence is 1 of every 4,200, and for male-assigned individuals, it is 1 of every 2,500. Many insurance companies refuse to cover these or even less invasive biological treatments for people with gender dysphoria, but a growing number of states now prohibit such insurance exclusions (Steimetz, 2014).

sex-change surgery A surgical procedure that changes a person’s sex organs, features, and, in turn, sexual identity. Also known as sexual reassignment surgery.

sex-change surgery A surgical procedure that changes a person’s sex organs, features, and, in turn, sexual identity. Also known as sexual reassignment surgery.

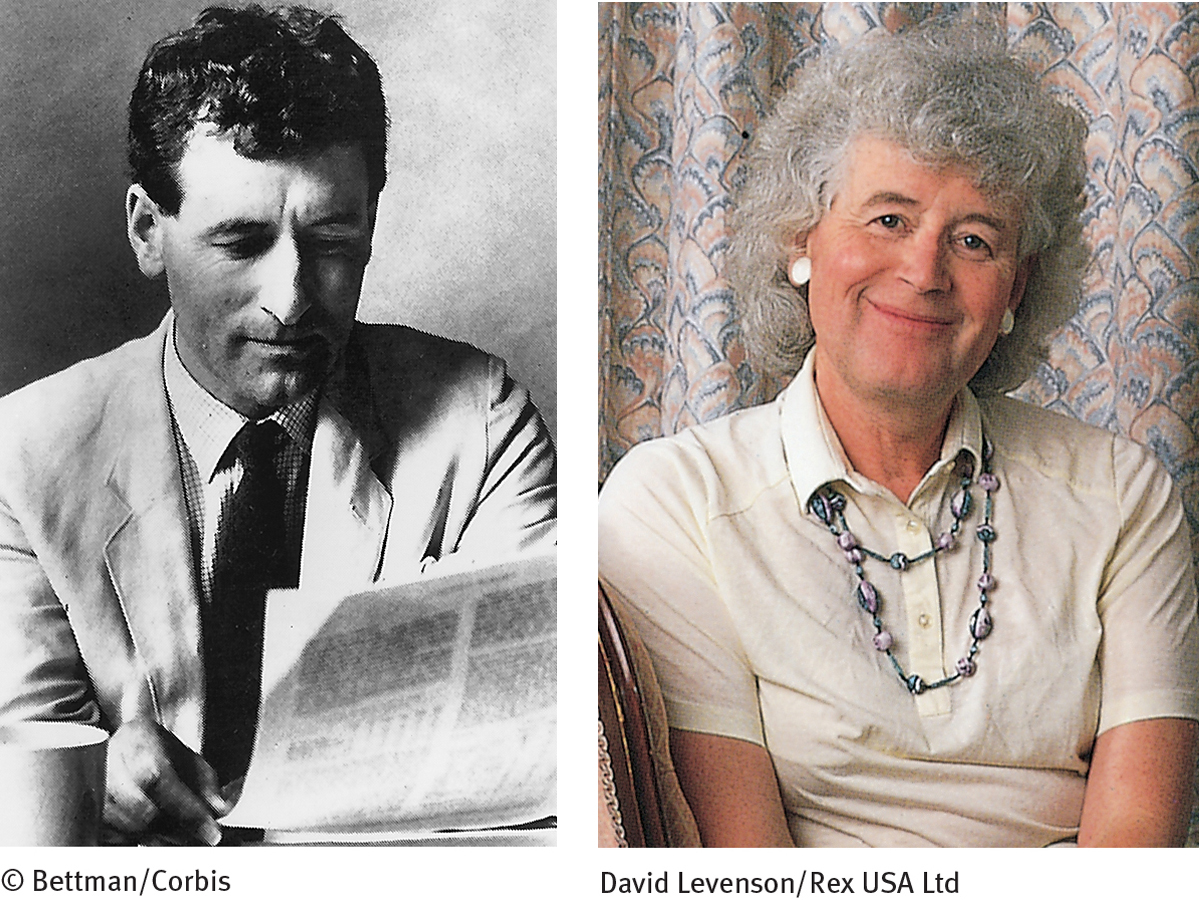

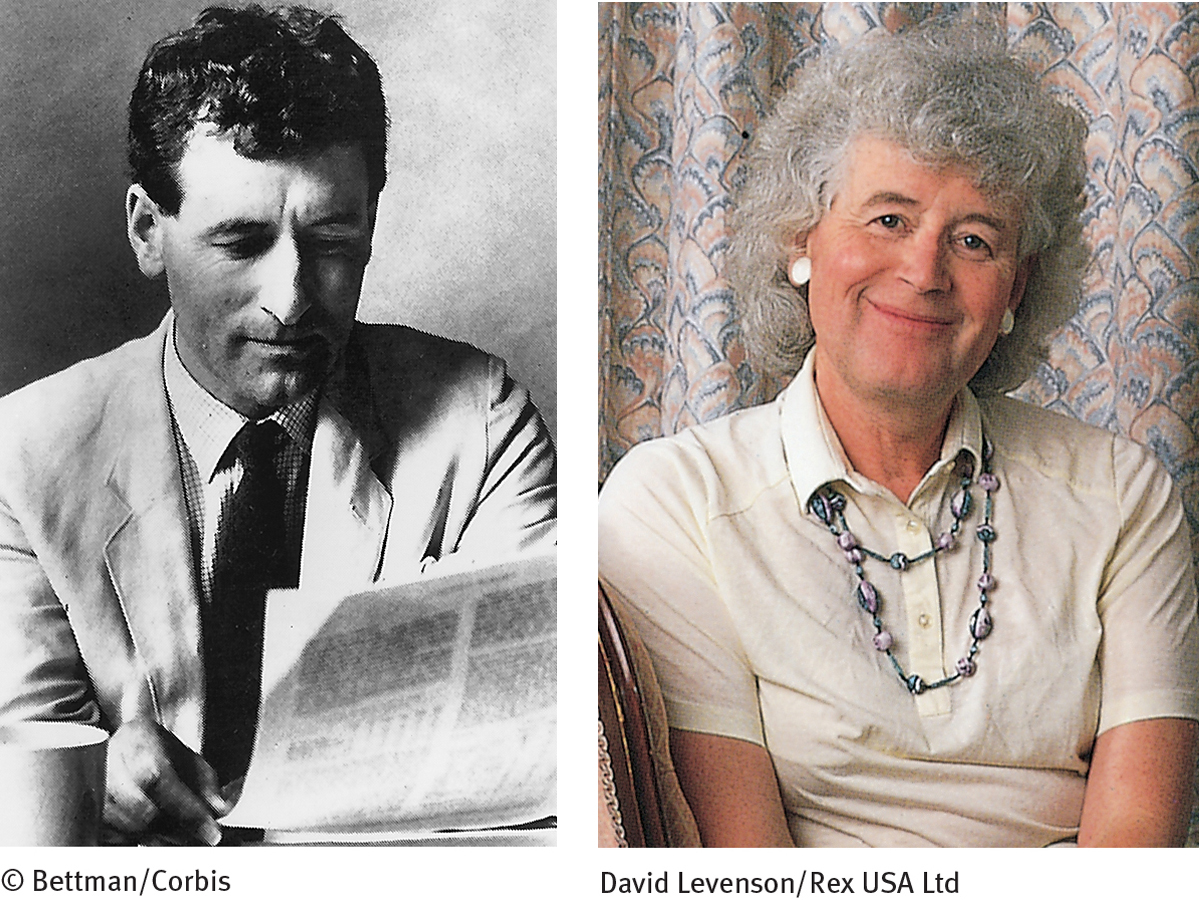

Pioneers James and Jan Feeling like a woman trapped in a man’s body, British writer James Morris (left) underwent sex-change surgery, described in a 1974 autobiography, Conundrum. Today Jan Morris (right) is a successful author and is comfortable with her change of gender.

Clinicians have debated heatedly whether sexual reassignment surgery is an appropriate treatment for gender dysphoria (Gozlan, 2011). Some consider it a humane solution, perhaps the most satisfying one to many people with the pattern. Others argue that sexual reassignment is a “drastic nonsolution” for a complex disorder. Either way, such surgery appears to be on the increase (Allison, 2010; Horton, 2008).

Research into the outcomes of sexual reassignment surgery has yielded mixed findings. On the one hand, in a number of studies, the majority of patients—both female-assigned and male-assigned—report satisfaction with the outcome of the surgery, improvements in self-satisfaction and interpersonal interactions, and improvements in sexual functioning (Judge et al., 2014; Johansson et al., 2010; Klein & Gorzalka, 2009). On the other hand, several studies have yielded less favorable findings. A long-term follow-up study in Sweden, for example, found that although sexually reassigned participants did show a reduction in gender dysphoria, they also had a higher rate of psychological disorders and of suicide attempts than the general population (Dhejne et al., 2011). People with serious pretreatment psychological disturbances (for example, a personality disorder) seem most likely to later regret the surgery (Carroll, 2007). All of this argues for careful screening prior to surgical interventions, continued research to better understand both the patterns themselves and the long-term impact of the surgical procedures, and, more generally, better clinical care for transgender people.

Page 460

MediaSpeak

A Different Kind of Judgment

By Angela Woodall, Oakland Tribune

Few county judges command standing ovations before they say a word, nor do they compel hate mail from strangers halfway around the world.

Alameda County Superior Court Judge Victoria Kolakowski receives both. She is the first transgender person elected as a trial judge and one of the very few elected to any office. “No, I am not going to be able to get you out of things,” she said jokingly to an audience of transgender advocates … two weeks after her upset victory…. “I had a chance to serve. If my being visible helps a community that is often ignored and looked down upon, then I am happy. If not me, then who?”

But it took years of rejection and perseverance to get from Michael Kolakowski to 49-year-old Judge Victoria Kolakowski, even though as a child she hoped and prayed to wake up in a female body. “I guess the prayer was answered,” she said. “But not for a long time afterward.” …

Kolakowski, a New York native, is a carefully groomed, mildly spoken brunette of average build who usually appears wearing glasses, modest makeup, dark pantsuits and pumps. In other words, she looks a lot like a conservatively dressed judge….

[Back when she was a teenager], the Internet did not exist, and information about transsexuals was unavailable to minors, Kolakowski said. At Louisiana State University, she finally found some books in the college library about transsexuality and realized that she was not alone. But when she told her parents, they took her to the emergency room of the hospital. This started an on-again, off-again series of counseling and therapy that lasted for a decade.

Do you believe that a sex change presents more problems for members of certain occupations (for example, a judge or police officer) than others (for example, a model or a writer)?

Kolakowski eventually married, came out with her wife during law school and began her transition to becoming a woman on April 1, 1989. It was her last semester at LSU. She was 27. Three years later, she underwent surgery to complete her transition to a woman.

She was a 30-year-old lawyer with five degrees on her resume. So she had no problem attracting job offers—only to be rejected when she walked into the interview.

Rejection is one of the commonalities for transgender women and men, and the pain can run deep. Some of the transgender lawyers Kolakowski knew killed themselves.

A new kind of role model Judge Victoria Kolakowski (left) waves during the 41st annual Gay Pride parade in San Francisco, June 26, 2011.

Kolakowski attributes her resilience to her faith—she also holds a master’s degree in divinity—and the support of “some very loving people.” That includes her parents and her second wife…. They wed in 2006.

By then, Kolakowski had become an administrative law judge…. Her chance to run for the Superior Court bench came in 2008…. Kolakowski didn’t win, but she tried again in 2010. “This time, things were different, and in June, I came in first,” she said.

The spotlight turned in her direction because she became a symbol of success for the transgender community. But she also has become a target. The more successful you are, the more backlash you are likely to get, she said, “and that backlash can be violent.” … [T]wo transgender women were killed in Houston last year, even though voters there elected a transgender municipal judge in November…. “We’re dealing with people who don’t know us and don’t really understand who we are,” she said.

Kolakowski is also mindful that she must be sensitive to the dignity of the office voters elected her to. Some people, she predicted, will accuse her of “acting inappropriately.” But she said: “This is what it is. I was elected based on my qualifications. It just happens to be historic.”

“Vicky Kolakowski Overcame Discrimination to Become Nation’s First Transgender Trial Judge.” Angela Woodall, Oakland Tribune, 12/30/2010. Used with permission of The Oakland Tribune © 2014. All rights reserved.

Page 461

gender dysphoria A disorder in which a person persistently feels clinically significant distress or impairment due to his or her assigned gender and strongly wishes to be a member of another gender.

gender dysphoria A disorder in which a person persistently feels clinically significant distress or impairment due to his or her assigned gender and strongly wishes to be a member of another gender.

sex-

sex-