14.1 The Clinical Picture of Schizophrenia

For years, schizophrenia was a “wastebasket category” for diagnosticians, particularly for those in the United States, where the label was at times assigned to anyone who acted unpredictably or strangely. The disorder is defined more precisely today, but still its symptoms vary greatly, and so do its triggers, course, and responsiveness to treatment (APA, 2013). In fact, a number of clinicians believe that schizophrenia is actually a group of distinct disorders that happen to have some features in common (Boutros et al., 2014; Arango & Carpenter, 2011).

PsychWatch

Mentally Ill Chemical Abusers

During the 1990s, Larry Hogue, nicknamed the “Wild Man of West 96th Street” by neighbors, became the best-

Hogue, a homeless man who lived on the streets of New York City’s Upper West Side, suffered from a combination of schizophrenia and cocaine and alcohol use disorder. As long as he did not abuse these substances, his schizophrenic disorder was responsive to treatment. But Hogue was unable to resist cocaine and alcohol, and the substances combined with his schizophrenia to produce a pattern of severe psychosis. While on the streets, particularly West 96th Street, Hogue behaved bizarrely. He would roam the streets in a menacing way, scream at passers-

Hogue was arrested more than 30 times and imprisoned at least six times. In prison, with substances out of reach, he would quickly calm down, become more coherent, and seem ready for treatment in the community. However, once back in the community, he would seek alcohol and cocaine instead of treatment, and the whole pattern would begin again. Only after the case gained national attention was Hogue committed to a mental health facility for treatment of his dual diagnosis problem.

Although Larry Hogue eventually received proper attention, today the MICA problem in the United States appears to be bigger than ever (Chakraborty et al., 2014; Kavanagh & Mueser, 2011). Between 20 and 50 percent of all people with chronic mental disorders may be MICAs.

MICAs tend to be young and male. They often rate below average in social functioning and school achievement and above average in poverty, acting-

The relationship between substance abuse and mental dysfunctioning is complex. A person’s mental disorder may precede his or her substance abuse, and he or she may take a drug as a form of self-

Treatment of MICAs has been undermined by the tendency of patients to hide their drug abuse problems and for clinicians to overlook such problems (Bahorik et al., 2014). Unrecognized substance abuse may lead to misdiagnosis and misunderstanding of the disorders. The treatment of MICAs is further complicated by the fact that many treatment facilities are designed and funded to treat either mental disorders or substance abuse; only some are equipped or willing to treat both (De Witte et al., 2014). As a result, it is not uncommon for MICA patients to be rejected as inappropriate for treatment in both substance abuse and mental health programs. Many such patients fall through the cracks in this way and find themselves in jail, like Larry Hogue, or in homeless shelters for want of the treatment they sought in vain (Kooyman & Walsh, 2011).

The problem of falling through the cracks is perhaps most poignantly seen in the case of homeless MICAs (Kooyman & Walsh, 2011; Felix, 2008). Researchers estimate that 10 to 20 percent of the homeless population may be MICAs. MICAs typically remain homeless longer than other homeless people and are more likely to have to contend with extremely harsh conditions, such as living on the winter streets rather than in a homeless shelter. Homeless MICAs need treatment programs committed to building trust and providing intensive case management (Coldwell & Bender, 2007; Egelko et al., 2002). In short, therapists must tailor treatment programs to MICAs’ unique combination of problems rather than expecting the MICAs to adapt to traditional forms of care.

Regardless of whether schizophrenia is a single disorder or several disorders, the lives of people who struggle with its symptoms are filled with pain and turmoil. One particularly coherent and articulate patient described what it is like to live with this disorder:

What … does schizophrenia mean to me? It means fatigue and confusion, it means trying to separate every experience into the real and the unreal and sometimes not being aware of where the edges overlap. It means trying to think straight when there is a maze of experiences getting in the way, and when thoughts are continually being sucked out of your head so that you become embarrassed to speak at meetings. It means feeling sometimes that you are inside your head and visualizing yourself walking over your brain, or watching another girl wearing your clothes and carrying out actions as you think them. It means knowing that you are continually “watched,” that you can never succeed in life because the laws are all against you and knowing that your ultimate destruction is never far away.

(Rollin, 1980, p. 162)

What Are the Symptoms of Schizophrenia?

Think back to Laura and Richard, the two people described at the beginning of the chapter. Both of them deteriorated from a normal level of functioning to become ineffective in dealing with the world (Laloyaux et al., 2014). Each had some of the symptoms found in schizophrenia. The symptoms can be grouped into three categories: positive symptoms (excesses of thought, emotion, and behavior), negative symptoms (deficits of thought, emotion, and behavior), and psychomotor symptoms (unusual movements or gestures). Some people with schizophrenia are more dominated by positive symptoms and others by negative symptoms, although most tend to have both kinds of symptoms to some degree. In addition, around half of those with schizophrenia have significant difficulties with memory and other kinds of cognitive functioning (Eich et al., 2014; Ordemann et al., 2014).

Positive SymptomsPositive symptoms are “pathological excesses,” or bizarre additions, to a person’s behavior. Delusions, disorganized thinking and speech, heightened perceptions and hallucinations, and inappropriate affect are the ones most often found in schizophrenia.

positive symptoms Symptoms of schizophrenia that seem to be excesses of or bizarre additions to normal thoughts, emotions, or behaviors.

positive symptoms Symptoms of schizophrenia that seem to be excesses of or bizarre additions to normal thoughts, emotions, or behaviors.

DELUSIONSMany people with schizophrenia develop delusions, ideas that they believe wholeheartedly but that have no basis in fact. The deluded person may consider the ideas enlightening or may feel confused by them. Some people hold a single delusion that dominates their lives and behavior; others have many delusions. Delusions of persecution are the most common in schizophrenia (APA, 2013). People with such delusions believe they are being plotted or discriminated against, spied on, slandered, threatened, attacked, or deliberately victimized. Laura believed that her neighbors were trying to irritate her and that other people were trying to harm her and her husband.

delusion A strange false belief firmly held despite evidence to the contrary.

delusion A strange false belief firmly held despite evidence to the contrary.

Philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche said, “Insanity in individuals is something rare—

People with schizophrenia may also have delusions of reference: they attach special and personal meaning to the actions of others or to various objects or events. Richard, for example, interpreted arrows on street signs as indicators of the direction he should take. People with delusions of grandeur believe themselves to be great inventors, religious saviors, or other specially empowered persons (see MediaSpeak below). And those with delusions of control believe their feelings, thoughts, and actions are being controlled by other people.

DISORGANIZED THINKING AND SPEECHPeople with schizophrenia may not be able to think logically (Briki et al., 2014) and may speak in peculiar ways (Millier et al., 2014). These formal thought disorders can cause the sufferer great confusion and make communication extremely difficult. Often such thought disorders take the form of positive symptoms (pathological excesses), as in loose associations, neologisms, perseveration, and clang.

formal thought disorder A disturbance in the production and organization of thought.

formal thought disorder A disturbance in the production and organization of thought.

People who have loose associations, or derailment, the most common formal thought disorder, rapidly shift from one topic to another, believing that their incoherent statements make sense. A single, perhaps unimportant word in one sentence becomes the focus of the next. One man with schizophrenia, asked about his itchy arms, responded:

loose associations A common thinking disturbance in schizophrenia, characterized by rapid shifts from one topic of conversation to another. Also known as derailment.

loose associations A common thinking disturbance in schizophrenia, characterized by rapid shifts from one topic of conversation to another. Also known as derailment.

The problem is insects. My brother used to collect insects. He’s now a man 5 foot 10 inches. You know, 10 is my favorite number. I also like to dance, draw, and watch television.

Some people with schizophrenia use neologisms, made-

HEIGHTENED PERCEPTIONS AND HALLUCINATIONSA deranged character in Edgar Allan Poe’s “The Tell-

Everything seems to grip my attention…. I am speaking to you just now, but I can hear noises going on next door and in the corridor. I find it difficult to shut these out, and it makes it more difficult for me to concentrate on what I am saying to you.

(McGhie and Chapman, 1961)

MediaSpeak

Putting Delusions to Use

By Benedict Carey, The New York Times, November 25, 2011

…Milt Greek pushed to his feet. It was Mother’s Day 2006, not long after his mother’s funeral, and he headed back home knowing that he needed help. A change in the medication for his schizophrenia, for sure. A change in focus, too; time with his family, to forget himself.

And, oh yes, he had to act on an urge expressed in his psychotic delusions: to save the world.

So after cleaning the yard around his house—

“I started feeling better, stronger, the next day,” said Mr. Greek, 49, a computer programmer who for years, before receiving medical treatment, had delusions of meeting God and Jesus. “I have such anxiety if I’m not organizing or doing some good work. I don’t feel right,” he said. “That’s what the psychosis has given me, and I consider it to be a gift.”

How might people distinguish the constructive features of their delusions from the harmful features?

Doctors generally consider the delusional beliefs of schizophrenia to be just that—

Mr. Greek’s regimen combines meditation, work and drug treatment with occasional visits to a therapist and a steady diet of charitable acts. Some of these are meant to improve the community; others are for co-

[Of late, Mr. Greek] has been especially stretched, between his work, various community projects, and traveling to speak, often to police groups, about how to understand psychotic thinking when dealing with people on the street. It was too much, and in August he visited his therapist again, and soon after made a deal with his wife. “She and I signed a contract identifying and limiting volunteer work I will do next year,” he said in an e-

November 26, 2011, “Lives Restored: Finding Purpose After Living With Delusion” by Benedict Carey. From The New York Times, 11/26/2011, © 2011 The New York Times. All rights reserved. Used by permission and protected by the copyright laws of the United States. The printing, copying, redistribution, or retransmission of this content without express written permission is prohibited.

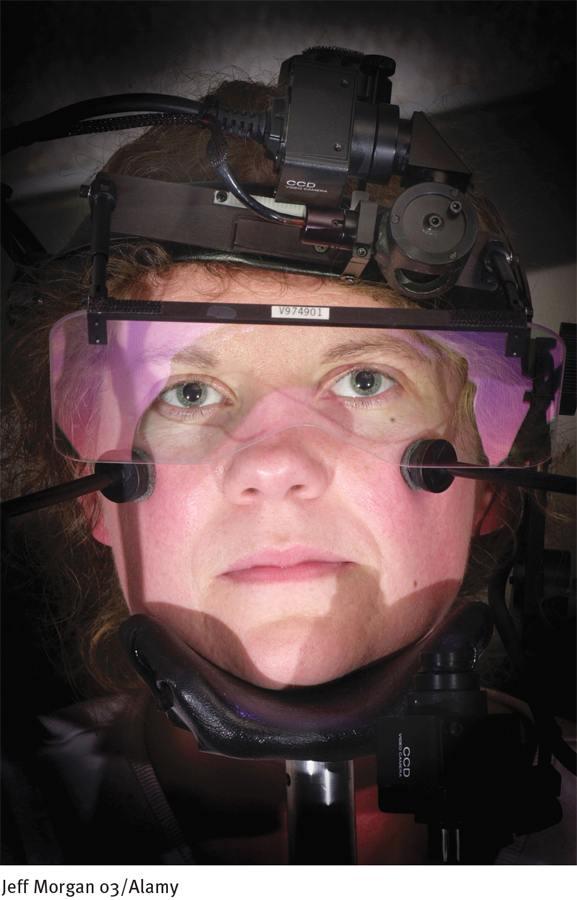

Laboratory studies repeatedly have found problems of perception and attention among people with schizophrenia (Bozikas et al., 2014; Park et al., 2011). In one study, participants were instructed to listen for a particular syllable recorded against an ongoing background of speech (Harris et al., 1985). As long as the background speech was kept simple, participants with and without schizophrenia were equally successful at picking out the syllable in question; but when the background speech was made more distracting, those with schizophrenia became less able to identify the syllable. In many studies, people with schizophrenia have also demonstrated deficiencies in smooth pursuit eye movement, weaknesses that may be related again to attention problems. When asked to keep their head still and track a moving object back and forth with their eyes, research participants with schizophrenia tend to perform more poorly than those without schizophrenia (Franco et al., 2014; Egan & Cannon, 2011).

The various perception and attention problems that people with schizophrenia have may develop years before the onset of the actual disorder (Remington et al., 2014; Goldberg et al., 2011; Cornblatt & Keilp, 1994). It is also possible that such problems further contribute to the memory impairments that are common to many people with schizophrenia (Ordemann et al., 2014).

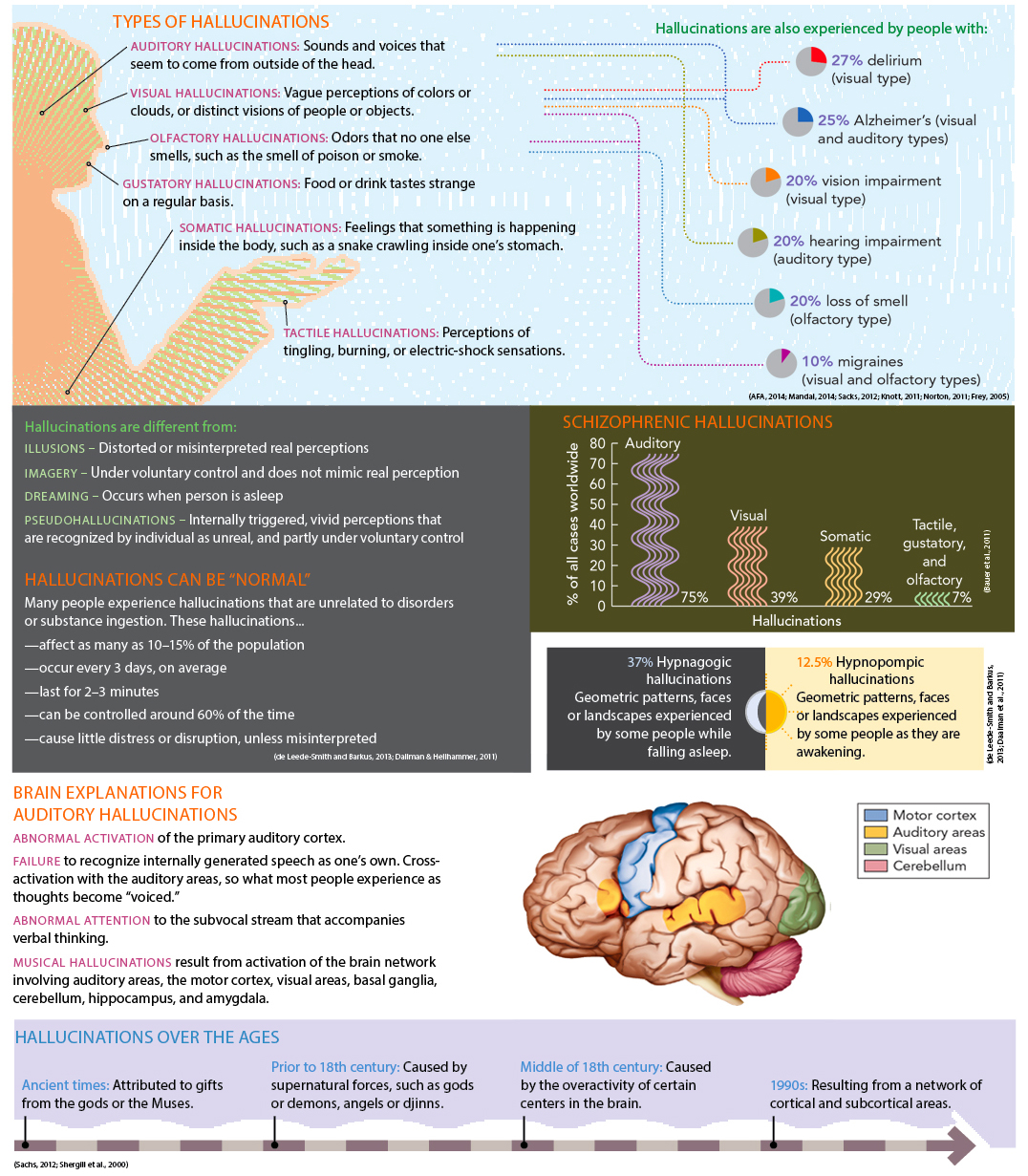

Another kind of perceptual problem in schizophrenia consists of hallucinations, perceptions that a person has in the absence of external stimuli (see InfoCentral below). People who have auditory hallucinations, by far the most common kind in schizophrenia, hear sounds and voices that seem to come from outside their heads. The voices may talk directly to the hallucinator, perhaps giving commands or warning of dangers, or they may be experienced as overheard:

hallucination The experiencing of sights, sounds, or other perceptions in the absence of external stimuli.

hallucination The experiencing of sights, sounds, or other perceptions in the absence of external stimuli.

The voices … were mostly heard in my head, though I often heard them in the air, or in different parts of the room. Every voice was different, and each beautiful, and generally, speaking or singing in a different tone and measure, and resembling those of relations or friends. There appeared to be many in my head, I should say upwards of fourteen. I divide them, as they styled themselves, or one another, into voices of contrition and voices of joy and honour.

(“Perceval’s Narrative,” in Bateson, 1974)

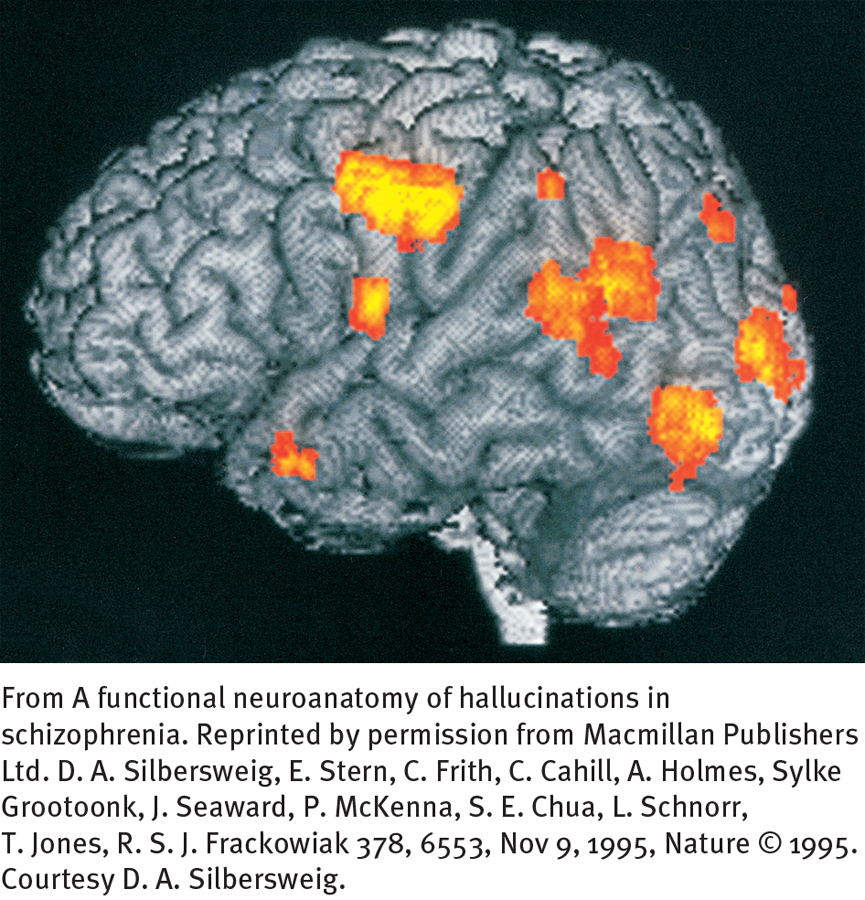

Research suggests that people with auditory hallucinations actually produce the nerve signals of sound in their brains, “hear” them, and then believe that external sources are responsible (Chun et al., 2014; Sarin & Wallin, 2014). One line of research measured blood flow in Broca’s area, the region of the brain that helps people produce speech (Homan et al., 2014; McGuire et al., 1996). The investigators found more blood flow in Broca’s area while patients were having auditory hallucinations. A related study instructed six men with schizophrenia to press a button whenever they had an auditory hallucination (Silbersweig et al., 1995). PET scans revealed increased activity near the surfaces of their brains, in the tissues of the auditory cortex, the brain’s hearing center, when they pressed the button.

InfoCentral

HALLUCINATIONS

Hallucinations are the experiencing of sights, sounds, smells, and other perceptions that occur in the absence of external stimuli.

Hallucinations can also involve any of the other senses (Stevenson, Langdon, & McGuire, 2011). Tactile hallucinations may take the form of tingling, burning, or electric-

Hallucinations and delusional ideas often occur together (Shiraishi et al., 2014). A woman who hears voices issuing commands, for example, may have the delusion that the commands are being placed in her head by someone else. A man with delusions of persecution may hallucinate the smell of poison in his bedroom or the taste of poison in his coffee. Might one symptom cause the other? Whatever the cause and whichever comes first, the hallucination and delusion eventually feed into each other.

I thought the voices I heard were being transmitted through the walls of my apartment and through the washer and dryer and that these machines were talking and telling me things. I felt that the government agencies had planted transmitters and receivers in my apartment so that I could hear what they were saying and they could hear what I was saying.

(Anonymous, 1996, p. 183)

INAPPROPRIATE AFFECTMany people with schizophrenia display inappropriate affect, emotions that are unsuited to the situation (Gard et al., 2011). They may smile when making a somber statement or upon being told terrible news, or they may become upset in situations that should make them happy. They may also undergo inappropriate shifts in mood. During a tender conversation with his wife, for example, a man with schizophrenia suddenly started yelling obscenities at her and complaining about her inadequacies.

inappropriate affect Displays of emotions that are unsuited to the situation; a symptom of schizophrenia.

inappropriate affect Displays of emotions that are unsuited to the situation; a symptom of schizophrenia.

In at least some cases, these emotions may be merely a response to other features of the disorder. Consider a woman with schizophrenia who smiles when told of her husband’s serious illness. She may not actually be happy about the news; in fact, she may not be understanding or even hearing it. She could, for example, be responding instead to another of the many stimuli flooding her senses, perhaps a joke coming from an auditory hallucination.

Negative SymptomsNegative symptoms are those that seem to be “pathological deficits,” characteristics that are lacking in a person. Poverty of speech, blunted and flat affect, loss of volition, and social withdrawal are commonly found in schizophrenia (Azorin et al., 2014; Rocca et al., 2014). Such deficits greatly affect one’s life and activities (Ferhava et al., 2014).

negative symptoms Symptoms of schizophrenia that seem to be deficits in normal thought, emotions, or behaviors.

negative symptoms Symptoms of schizophrenia that seem to be deficits in normal thought, emotions, or behaviors.

POVERTY OF SPEECHPeople with schizophrenia often have alogia, or poverty of speech, a reduction in speech or speech content. Some people with this negative kind of formal thought disorder think and say very little. Others say quite a bit but still manage to convey little meaning (Haas et al., 2014; Birkett et al., 2011). These problems are revealed in the following diary entry written in 1919 by Vaslav Nijinsky, one of the twentieth century’s great ballet dancers, as his pattern of schizophrenia was unfolding:

alogia A decrease in speech or speech content; a symptom of schizophrenia. Also known as poverty of speech.

alogia A decrease in speech or speech content; a symptom of schizophrenia. Also known as poverty of speech.

BETWEEN THE LINES

In Their Words

“I shouldn’t precisely have chosen madness if there had been any choice, but once such a thing has taken hold of you, you can’t very well get out of it.”

Vincent van Gogh, 1889

I do not wish people to think that I am a great writer or that I am a great artist nor even that I am a great man. I am a simple man who has suffered a lot. I believe I suffered more than Christ. I love life and want to live, to cry but cannot—

(Nijinsky, 1936)

RESTRICTED AFFECTMany people with schizophrenia have a blunted affect—they show less anger, sadness, joy, and other feelings than most people (Rocca et al., 2014). And some show almost no emotions at all, a condition known as flat affect. Their faces are still, their eye contact is poor, and their voices are monotonous. In some cases, people with these problems may have anhedonia, a general lack of pleasure or enjoyment. In other cases, however, the restricted affect may reflect an inability to express emotions as others do. One study had participants view very emotional film clips. The participants with schizophrenia showed less facial expression than the others; however, they reported feeling just as much positive and negative emotion and in fact displayed more skin arousal (Kring & Neale, 1996).

flat affect A marked lack of apparent emotions; a symptom of schizophrenia.

flat affect A marked lack of apparent emotions; a symptom of schizophrenia.

LOSS OF VOLITIONMany people with schizophrenia experience avolition, or apathy, feeling drained of energy and of interest in normal goals and unable to start or follow through on a course of action (Gard et al., 2014; Gold et al., 2014). This problem is particularly common in people who have had schizophrenia for many years, as if they have been worn down by it. Similarly, people with schizophrenia may feel ambivalence, or conflicting feelings, about most things. The avolition and ambivalence of Richard, the young man you read about earlier, made eating, dressing, and undressing impossible ordeals for him.

avolition A symptom of schizophrenia marked by apathy and an inability to start or complete a course of action.

avolition A symptom of schizophrenia marked by apathy and an inability to start or complete a course of action.

SOCIAL WITHDRAWALPeople with schizophrenia may withdraw from their social environment and attend only to their own ideas and fantasies (Gard et al., 2014; Pinkham, 2014). Because their ideas are illogical and confused, the withdrawal has the effect of distancing them still further from reality. The social withdrawal seems also to lead to a breakdown of social skills, including the ability to recognize other people’s needs and emotions accurately (Fogley, Warman, & Lysaker, 2014; Lysaker et al., 2014).

Psychomotor SymptomsPeople with schizophrenia sometimes experience psychomotor symptoms. Many move relatively slowly (Bervoets et al., 2014), and a number make awkward movements or repeated grimaces and odd gestures that seem to have a private purpose—

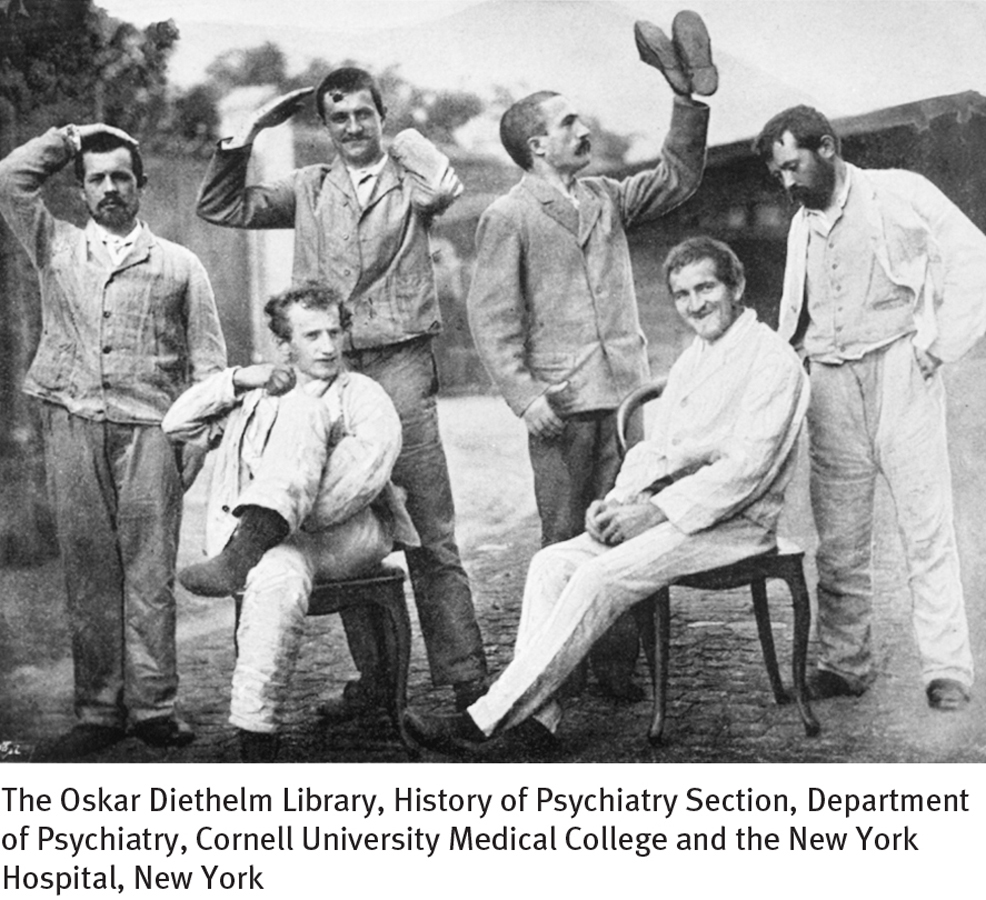

The psychomotor symptoms of schizophrenia may take certain extreme forms, collectively called catatonia. People in a catatonic stupor stop responding to their environment, remaining motionless and silent for long stretches of time. Recall how Richard would lie motionless and mute in bed for days. People with catatonic rigidity maintain a rigid, upright posture for hours and resist efforts to be moved. Still others exhibit catatonic posturing, assuming awkward, bizarre positions for long periods of time. They may, for example, spend hours holding their arms out at a 90-

catatonia A pattern of extreme psychomotor symptoms, found in some forms of schizophrenia, which may include cata-

catatonia A pattern of extreme psychomotor symptoms, found in some forms of schizophrenia, which may include cata-

What Is the Course of Schizophrenia?

Schizophrenia usually first appears between the person’s late teens and mid-

Many people with schizophrenia eventually enter a residual phase in which they return to a prodromal-

Each of these phases may last for days or for years. A fuller recovery from schizophrenia is more likely in people who functioned quite well before the disorder (had good premorbid functioning); whose initial disorder is triggered by stress, comes on abruptly, or develops during middle age; and who receive early treatment, preferably during the prodromal phase (Remberk et al., 2014; Conus et al., 2007). Relapses are apparently more likely during times of life stress (Bebbington & Kuipers, 2011, 2008).

Diagnosing Schizophrenia

DSM-

BETWEEN THE LINES

The Wrong Split

Despite popular misconceptions, people with schizophrenia do not have a “split” or multiple personality. That pattern is indicative of dissociative identity disorder.

Many researchers believe that in order to help predict the course of schizophrenia, there should be a distinction between so-