14.2 How Do Theorists Explain Schizophrenia?

As with many other kinds of disorders, biological, psychological, and sociocultural theorists have each proposed explanations for schizophrenia. So far, the biological explanations have received by far the most research support. This is not to say that psychological and sociocultural factors play no role in the disorder. Rather, a diathesis-

Biological Views

What is arguably the most enlightening research on schizophrenia during the past several decades has come from genetic and biological investigations. These studies have revealed the key roles of inheritance and brain activity in the development of schizophrenia and have opened the door to important treatment changes.

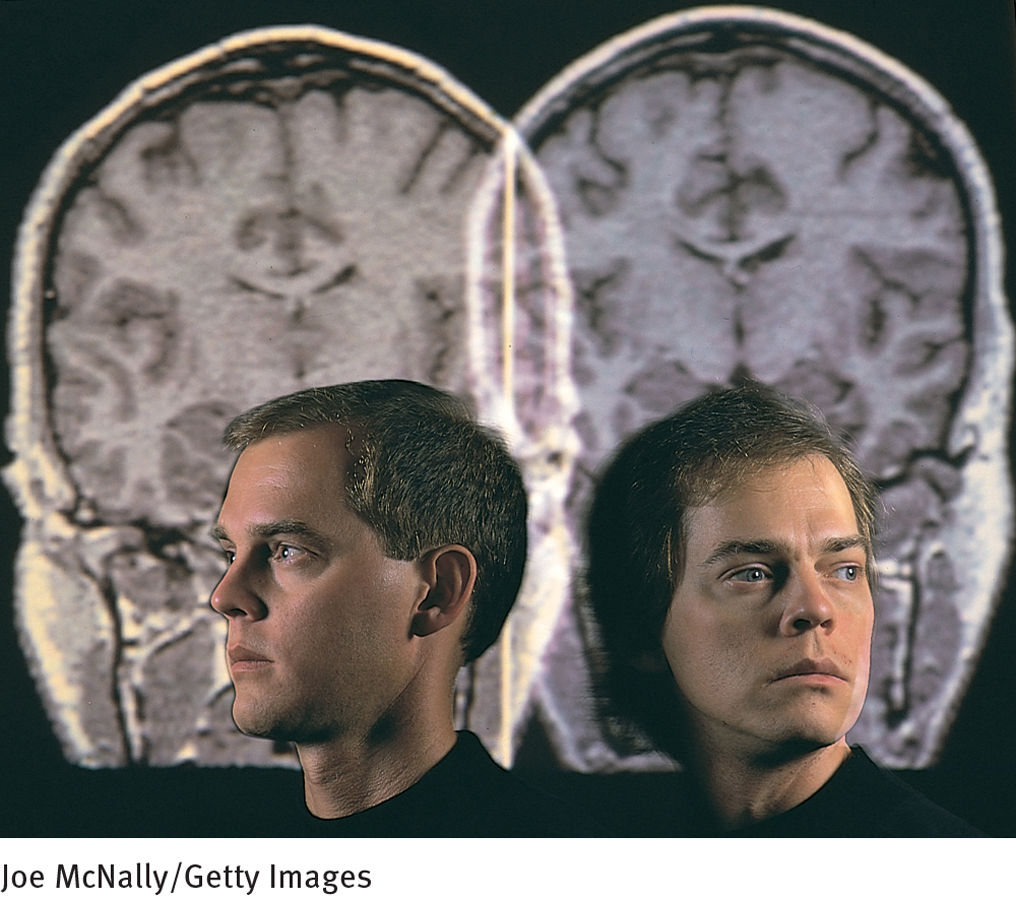

Genetic FactorsFollowing the principles of the diathesis-

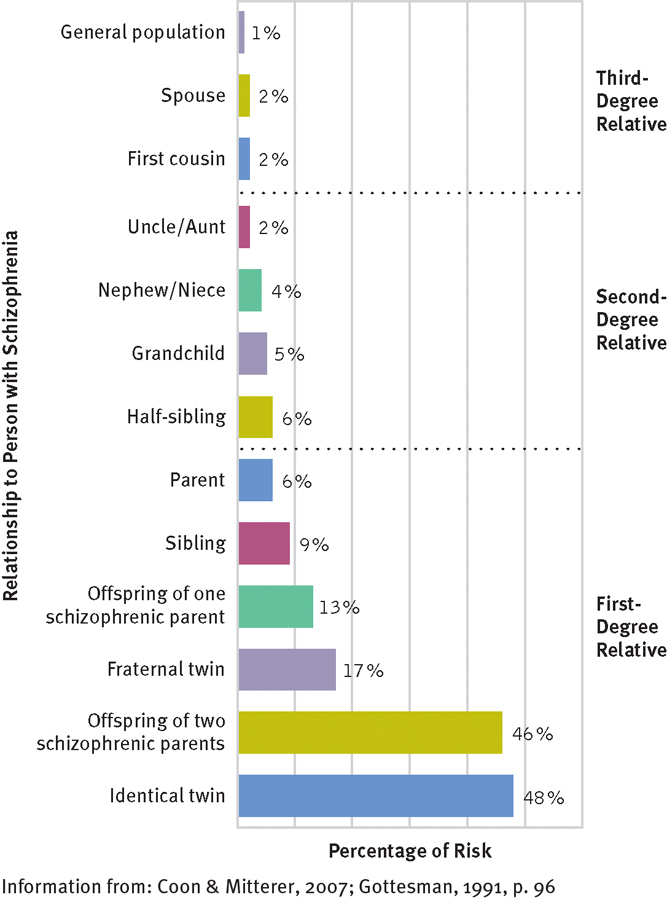

ARE RELATIVES VULNERABLE?Family pedigree studies have found repeatedly that schizophrenia and schizophrenia-

Family links

People who are biologically related to someone with schizophrenia have a heightened risk of developing the disorder during their lifetimes. The closer the biological relationship (that is, the more similar the genetic makeup), the greater the risk of developing the disorder.

As you saw earlier, 1 percent of the general population develops schizophrenia. The prevalence rises to 3 percent among second-

IS AN IDENTICAL TWIN MORE VULNERABLE THAN A FRATERNAL TWIN?Twins, who are among the closest of relatives, have in particular been studied by schizophrenia researchers. If both members of a pair of twins have a particular trait, they are said to be concordant for that trait. If genetic factors are at work in schizophrenia, identical twins (who share all their genes) should have a higher concordance rate for schizophrenia than fraternal twins (who share only some genes). This expectation has been supported consistently by research (Higgins & George, 2007; Gottesman, 1991). Studies have found that if one identical twin develops schizophrenia, there is a 48 percent chance that the other twin will do so as well. If the twins are fraternal, on the other hand, the second twin has approximately a 17 percent chance of developing the disorder.

PsychWatch

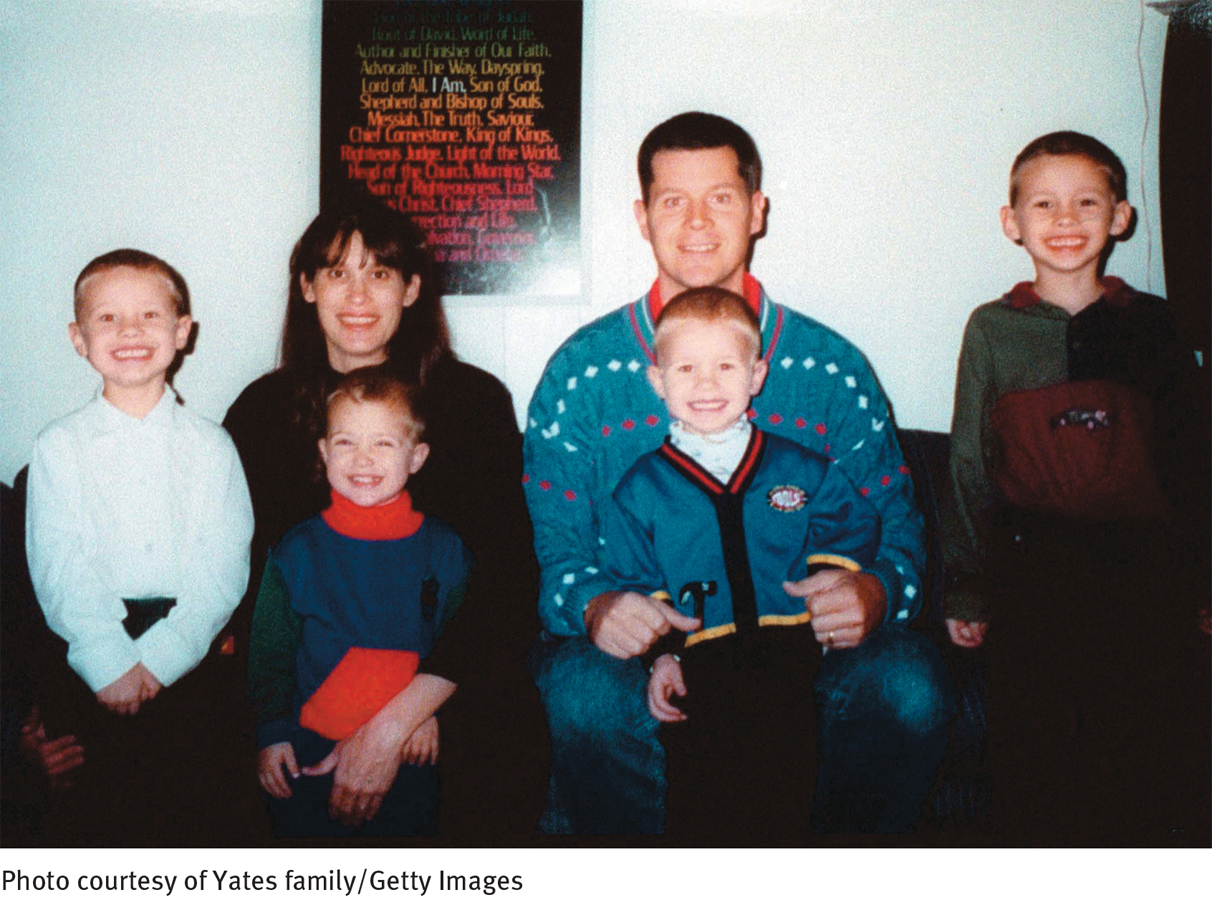

Postpartum Psychosis: The Case of Andrea Yates

On the morning of June 20, 2001, the nation’s television viewers watched in horror as officials escorted 36-

In Chapter 7 you read that as many as 80 percent of mothers experience “baby blues” soon after giving birth, while between 10 and 30 percent display the clinical syndrome of postpartum depression. Yet another postpartum disorder that has become all too familiar to the public in recent times, by way of cases such as that of Andrea Yates, is postpartum psychosis (Engqvist et al., 2014)

Postpartum psychosis affects about 1 to 2 of every 1,000 mothers who have recently given birth (Posmontier, 2010). The symptoms apparently are triggered by the enormous shift in hormone levels that takes place after delivery (Meinhard et al., 2014). Within days or at most a few months of childbirth, the woman develops signs of losing touch with reality, such as delusions (for example, she may become convinced that her baby is the devil); hallucinations (perhaps hearing voices); extreme anxiety, confusion, and disorientation; disturbed sleep; and illogical or chaotic thoughts (for example, thoughts about killing herself or her child).

Women with a history of bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, or depression are particularly vulnerable to the disorder (Di Florio et al., 2014; Read & Purse, 2007). Women who have previously experienced postpartum depression or postpartum psychosis have an increased likelihood of developing postpartum psychosis after subsequent births (Bergink et al., 2012; Nonacs, 2007). Andrea Yates, for example, had developed signs of postpartum depression (and perhaps postpartum psychosis) and attempted suicide after the birth of her fourth child. At that time, however, she appeared to respond well to a combination of medications, including antipsychotic drugs, and so she and her husband later decided to conceive a fifth child. Although they were warned that she was at risk for serious postpartum symptoms once again, they believed that the same combination of medications would help if the symptoms were to recur (King, 2002).

After the birth of her fifth child, the symptoms did in fact recur, along with features of psychosis. Yates again attempted suicide. Although she was hospitalized twice and treated with various medications, her condition failed to improve. Six months after giving birth to Mary, her fifth child, she drowned all five of her children.

Most clinicians who are knowledgeable about this rare disorder agree that Yates was a victim of postpartum psychosis. Although only a fraction of women with the disorder actually harm their children (estimates run as high as 4 percent), the Yates case reminds us that such an outcome is possible (Posmontier, 2010; Read & Purse, 2007). The case also reminds us that early detection and treatment are critical (O’Hara & Wisner, 2014; Doucet et al., 2011).

On March 13, 2002, a Texas jury found Andrea Yates guilty of murdering her children and sentenced her to life in prison. She had pleaded not guilty by reason of insanity during her trial, but the jury concluded within hours that despite her profound disorder, she did know right from wrong. The verdict itself stirred debate throughout the United States, but clinicians and the public alike were united in the belief that, at the very least, the mental health system had tragically failed this woman and her five children.

A Texas appeals court later reversed Yates’ conviction, citing the inaccurate testimony of a prosecution witness, and on July 26, 2006, after a new trial, Yates was found not guilty by reason of insanity and was sent to a high-

Once again, however, factors other than genetics may explain these concordance rates. For example, if one twin is exposed to a particular danger during the prenatal period, such as an injury or virus, the other twin is likely to be exposed to it as well. This is especially true for identical twins, whose prenatal environment is especially similar. Thus a predisposition to schizophrenia could be the result of a prenatal problem, and twins, particularly identical twins, would still be expected to have a higher concordance rate.

What factors, besides genetic ones, might account for the elevated rate of schizophrenia among relatives of people with this disorder?

ARE THE BIOLOGICAL RELATIVES OF AN ADOPTEE VULNERABLE?Adoption studies look at adults with schizophrenia who were adopted as infants and compare them with both their biological and their adoptive relatives. Because they were reared apart from their biological relatives, similar symptoms in those relatives would indicate genetic influences. Conversely, similarities to their adoptive relatives would suggest environmental influences. Researchers have repeatedly found that the biological relatives of adoptees with schizophrenia are more likely than their adoptive relatives to develop schizophrenia or another schizophrenia spectrum disorder (Andreasen & Black, 2006; Kety, 1988, 1968).

WHAT DO GENETIC LINKAGE AND MOLECULAR BIOLOGY STUDIES SUGGEST?As with bipolar disorders (see Chapter 7), researchers have run studies of genetic linkage and molecular biology to pinpoint the possible genetic factors in schizophrenia (Singh et al., 2014; Winchester et al., 2014). In one approach, they select large families in which schizophrenia is very common, take blood and DNA samples from all members of the families, and then compare gene fragments from members with and without schizophrenia. Applying this procedure to families from around the world, various studies have identified possible gene defects on chromosomes 1, 2, 6, 8, 10, 13, 15, 18, 20, and 22 and on the X chromosome, each of which may help predispose a person to develop schizophrenia (Huang et al., 2014; Muller, 2014).

These varied findings may indicate that some of the suspected gene sites are cases of mistaken identity and do not actually contribute to schizophrenia. Alternatively, it may be that different kinds of schizophrenia are linked to different genes. It is most likely, however, that schizophrenia, like a number of other disorders, is a polygenic disorder, caused by a combination of gene defects (Goudriaan et al., 2014; Purcell et al., 2014).

How might genetic factors lead to the development of schizophrenia? Research has pointed to two kinds of biological abnormalities that could conceivably be inherited—

Biochemical AbnormalitiesAs you have read, the brain is made up of neurons whose electrical impulses (or “messages”) are transmitted from one to another by neurotransmitters. After an impulse arrives at a receiving neuron, it travels down the axon of that neuron until it reaches the nerve ending. The nerve ending then releases neurotransmitters that travel across the synaptic space and bind to receptors on yet another neuron, thus relaying the message to the next “station.” This neuron activity is known as “firing.”

Over the past four decades, researchers have developed a dopamine hypothesis to explain their findings on schizophrenia: certain neurons that use the neurotransmitter dopamine (particularly neurons in the striatum region of the brain) fire too often and transmit too many messages, thus producing the symptoms of schizophrenia (Brisch et al., 2014; During et al., 2014; Laruelle, 2014). This hypothesis has undergone challenges and adjustments in recent years, but it is still the foundation for current biochemical explanations of schizophrenia (Rao & Remington, 2014). The chain of events leading to this hypothesis began with the accidental discovery of antipsychotic drugs, medications that help remove the symptoms of schizophrenia. As you will see in Chapter 15, the first group of antipsychotic medications, the phenothiazines, were discovered in the 1950s by researchers who were looking for better antihistamine drugs to combat allergies. Although phenothiazines failed as antihistamines, it soon became obvious that they were effective in reducing schizophrenic symptoms, and clinicians began to prescribe them widely (Adams et al., 2014).

dopamine hypothesis The theory that schizophrenia results from excessive activity of the neurotransmitter dopamine.

dopamine hypothesis The theory that schizophrenia results from excessive activity of the neurotransmitter dopamine.

antipsychotic drugs Drugs that help correct grossly confused or distorted thinking.

antipsychotic drugs Drugs that help correct grossly confused or distorted thinking.

phenothiazines A group of antihista-

phenothiazines A group of antihista-

Researchers later learned that these early antipsychotic drugs often produce troublesome muscular tremors, symptoms that are identical to the central symptom of Parkinson’s disease, a disabling neurological illness. This undesired reaction to antipsychotic drugs offered the first important clue to the biology of schizophrenia. Scientists already knew that people who suffer from Parkinson’s disease have abnormally low levels of the neurotransmitter dopamine in some areas of the brain and that lack of dopamine is the reason for their uncontrollable shaking. If antipsychotic drugs produce Parkinsonian symptoms in people with schizophrenia while removing their psychotic symptoms, perhaps the drugs reduce dopamine activity. And, scientists reasoned further, if lowering dopamine activity helps remove the symptoms of schizophrenia, perhaps schizophrenia is related to excessive dopamine activity in the first place.

HOW STRONG IS THE DOPAMINE-

Support for the dopamine hypothesis has also come from research on amphetamines, drugs that, as you saw in Chapter 12, stimulate the central nervous system. Investigators first noticed during the 1970s that people who take high doses of amphetamines may develop amphetamine psychosis—a syndrome very similar to schizophrenia (Hawken & Beninger, 2014; Li et al., 2014). They also found that antipsychotic drugs can reduce the symptoms of amphetamine psychosis, just as they reduce the symptoms of schizophrenia. Eventually researchers learned that amphetamines and similar stimulant drugs increase dopamine activity in the brain, thus producing schizophrenia-

Investigators have located areas of the brain that are rich in dopamine receptors and have found that phenothiazines and other antipsychotic drugs bind to many of these receptors (Yoshida et al., 2014). Apparently the drugs are dopamine antagonists—drugs that bind to dopamine receptors, prevent dopamine from binding there, and so prevent the neurons from firing. Researchers have identified five kinds of dopamine receptors in the brain—

BETWEEN THE LINES

Primary Causes of Premature Death Among People with Schizophrenia

Suicide

Accidents

Inadequate medical care

Infections, heart disease, diabetes

Unhealthy lifestyles

Homelessness

(Information from: Kooyman & Walsh, 2011; Newcomer & Leucht, 2011)

WHAT IS DOPAMINE’S PRECISE ROLE?These and related findings suggest that in schizophrenia, messages traveling from dopamine-

MindTech

Can Computers Develop Schizophrenia?

One of the leading explanations for schizophrenia holds that people with this disorder are overwhelmed by the stimuli around them. According to this theory, excessive dopamine floods the brains of people with schizophrenia, leading them to process stimulus information at too high a rate. They are unable to forget or disregard extraneous sensory information, which leads to a process dubbed “hyperlearning.” As a result of hyperlearning, people with schizophrenia cannot distinguish between reality and illusion or recognize the barriers between unrelated pieces of information or unrelated experiences (Boyle, 2011).

Researchers in the computer science department at the University of Texas at Austin created a study to test the hyperlearning theory (Hoffman et al., 2011). They built a computer neural network they called DISCERN, and programmed it to store information in ways that parallel the ways the human brain organizes words, sentences, and other bits of information into knowledge and memories. The researchers then simulated the effects of a dopamine flood by programing the computer system to process information at a faster and faster rate, while at the same time programming it to ignore less and less data.

Can you think of alternative—

The researchers reported that after DISCERN had finished being reprogrammed, it began to display patterns of functioning that were similar to those found in people with schizophrenia. For example, while retelling stories that it had been programmed to recall, DISCERN began to place itself at the center of the retelling, often telling fantastical, delusional stories. In one instance, for example, the computer claimed that it had been responsible for a terrorist bombing. The researchers further found that the computer’s delusional stories were similar to those produced by human participants with schizophrenia after they had been given similar pieces of information.

This study may bring to mind the famous film 2001: A Space Odyssey, in which a computer named “HAL,” with the capacity for artificial intelligence, develops a mental disorder when presented with orders that it could not logically reconcile. Of course, HAL’s actions in that film still remain the stuff of science fiction, and the UT Austin study provides, at most, limited support for the hyperlearning model of schizophrenia. Nevertheless, the study suggests that computer neural networks, which can be tightly controlled and manipulated, may eventually provide clinical researchers with a viable model of how the human brain works and breaks down. ![]()

Why might dopamine be overactive in people with schizophrenia? It may be that people with schizophrenia have a larger-

Though enlightening, the dopamine hypothesis has certain problems. The biggest challenge to it has come with the recent discovery of a new group of antipsychotic drugs, initially referred to as atypical antipsychotic drugs and now called second-generation antipsychotic drugs, which are often more effective than the traditional ones. The new drugs bind not only to D-

second-generation antipsychotic drugs A relatively new group of antipsychotic drugs whose biological action is different from that of the traditional anti-

second-generation antipsychotic drugs A relatively new group of antipsychotic drugs whose biological action is different from that of the traditional anti-

In yet another challenge to the dopamine hypothesis, some theorists claim that excessive dopamine activity contributes primarily to the positive symptoms of schizophrenia such as delusions and hallucinations. In support of that notion, it turns out that positive symptoms respond well to the conventional antipsychotic drugs, which bind so strongly to D-

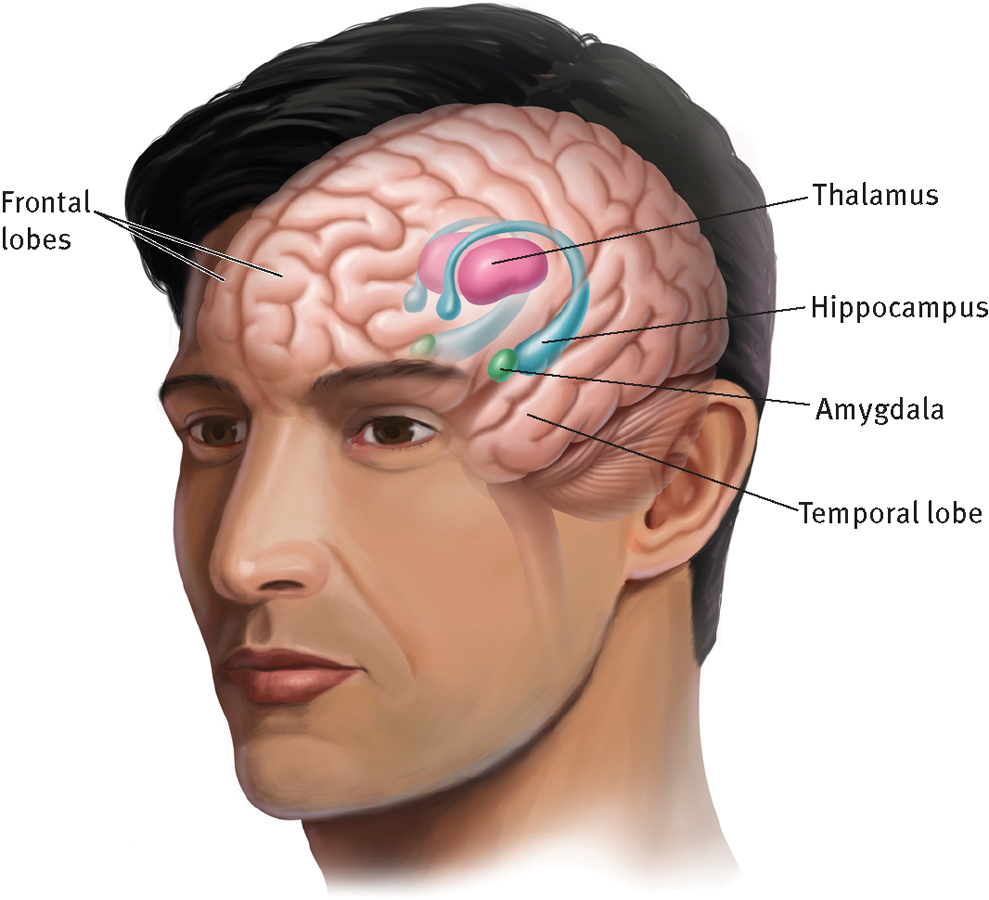

Abnormal Brain StructureDuring the past decade, researchers have also linked schizophrenia, particularly cases dominated by negative symptoms, to abnormalities in brain structure (Millan et al., 2014; Shinto et al., 2014). Using brain scans, they have found, for example, that many people with schizophrenia have enlarged ventricles—the brain cavities that contain cerebro-

It may be that enlarged ventricles are actually a sign that nearby parts of the brain have not developed properly or have been damaged, and perhaps these problems are the ones that help produce schizophrenia. In fact, studies suggest that some patients with schizophrenia also have smaller temporal and frontal lobes than other people, smaller amounts of cortical white and gray matter and, perhaps most important, abnormal blood flow—

Biology of schizophrenia

Some studies show that people with schizophrenia have relatively small temporal and frontal lobes, as well as abnormalities in brain structures such as the hippocampus, amygdala, and thalamus.

Viral ProblemsWhat might cause the biochemical and structural abnormalities found in many cases of schizophrenia? Various studies have pointed to genetic factors, poor nutrition, fetal development, birth complications, immune reactions, and toxins (Brown, 2012; Clarke et al., 2012; Borrajo et al., 2011). In addition, some investigators suggest that the brain abnormalities may result from exposure to viruses before birth. Perhaps the viruses enter the fetus’ brain and interrupt proper brain development, or perhaps the viruses remain quiet until puberty or young adulthood, when, activated by changes in hormones or by another viral infection, they help to bring about schizophrenic symptoms (Fox, 2010; Torrey, 2001, 1991).

Some of the evidence for the viral theory comes from animal model investigations, and other evidence is circumstantial, such as the finding that an unusually large number of people with schizophrenia are born during the winter (Patterson, 2012; Fox, 2010). The winter birth rate among people with schizophrenia is 5 to 8 percent higher than among other people (Harper & Brown, 2012; Tamminga et al., 2008). This could be because of an increase in fetal or infant exposure to viruses at that time of year. The viral theory has also received support from investigations of fingerprints. Normally, identical twins have almost identical numbers of fingerprint ridges. People with schizophrenia, however, often have significantly more or fewer ridges than their nonschizophrenic identical twins (van Os et al., 1997; Torrey et al., 1994). Fingerprints form in the fetus during the second trimester of pregnancy, just when the fetus is most vulnerable to certain viruses. Thus the fingerprint irregularities of some people with schizophrenia could reflect a viral infection contracted during the prenatal period, an infection that also predisposed the individuals to schizophrenia.

More direct evidence for the viral theory of schizophrenia comes from studies showing that mothers of people with schizophrenia were more likely to have been exposed to the influenza virus during pregnancy than were mothers of people without schizophrenia (Canetta et al., 2014; Brown & Patterson, 2011; Fox, 2010). Other studies have found antibodies to certain viruses, including viruses usually found in animals, in the blood of 40 percent of research participants with schizophrenia (Leweke et al., 2004; Torrey et al., 1994). The presence of such antibodies suggests that these people had at some time been exposed to those particular viruses.

Together, the biochemical, brain structure, and viral findings are shedding much light on the mysteries of schizophrenia. At the same time, it is important to recognize that many people who have these biological abnormalities never develop schizophrenia. Why not? Possibly, as you read earlier, because biological factors merely set the stage for schizophrenia, while key psychological and sociocultural factors must be present for the disorder to appear.

Psychological Views

When schizophrenia investigators began to identify genetic and biological factors during the 1950s and 1960s, many clinicians abandoned the psychological theories of the disorder. During the past few decades, however, the tables have been turned and psychological factors are once again being considered as important pieces of the schizophrenia puzzle (Green et al., 2014). The leading psychological theories come from the psychodynamic, behavioral, and cognitive perspectives.

BETWEEN THE LINES

Paternal Impact

People whose fathers were over 50 years of age when they were born are more likely to develop schizophrenia than people who are born to fathers under 50 years old (Crystal et al., 2012; Petersen et al, 2011). Various explanations, both biological and psychological, have been offered for this relationship, but researchers have yet to make sense of it.

The Psychodynamic ExplanationFreud (1924, 1915, 1914) believed that schizophrenia develops from two psychological processes: (1) regression to a pre-

In support of Freud’s theory, some studies show that people with schizophrenia have great difficulty forming an integrated sense of self (Lysaker et al., 2014). In addition, studies have often found that people with schizophrenia went through severe stress or traumas early in their lives (Bebbington & Kuipers, 2011). Beyond these findings, however, Freud’s explanation for the disorder has received little research support.

Why have parents and family life so often been blamed for schizophrenia, and why do such explanations continue to be influential?

Years later, noted psychodynamic clinician Frieda Fromm-

schizophrenogenic mother A type of mother—

schizophrenogenic mother A type of mother—

Fromm-

The Behavioral ViewBehaviorists usually cite operant conditioning and principles of reinforcement as the cause of schizophrenia. They propose that most people become quite proficient at reading and responding to social cues—

Support for the behavioral position has been circumstantial. As you’ll see in Chapter 15, researchers have found that patients with schizophrenia are capable of learning at least some appropriate verbal and social behaviors if hospital personnel consistently ignore their bizarre responses and reinforce normal responses with cigarettes, food, attention, or other rewards (Kopelowicz, Liberman, & Zarate, 2007). If bizarre verbal and social responses can be eliminated by appropriate reinforcements, perhaps they were acquired through improper learning in the first place. Of course, an effective treatment does not necessarily indicate the cause of a disorder. Today the behavioral view is usually considered at best a partial explanation for schizophrenia. Although it may help explain why a given person displays more psychotic behavior in some situations than in others, it is too limited, in the opinion of many, to account for schizophrenia’s origins and its many symptoms.

BETWEEN THE LINES

“If you talk to God, you are praying. If God talks to you, you have schizophrenia.”

Thomas Szasz, psychiatric theorist

The Cognitive ViewA leading cognitive explanation of schizophrenia is congruent with the biological view that during hallucinations and related perceptual difficulties the brains of people with schizophrenia are actually producing strange and unreal sensations—

Researchers have established that people with schizophrenia do indeed experience sensory and perceptual problems. As you saw earlier, many have hallucinations and most have trouble keeping their attention focused. But researchers have yet to provide clear, direct support for the cognitive notion that misinterpretations of such sensory problems actually produce a syndrome of schizophrenia.

Sociocultural Views

Sociocultural theorists, recognizing that people with mental disorders are subject to a wide range of social and cultural forces, believe that multicultural factors, social labeling, and family dysfunctioning all contribute to schizophrenia. Research has yet to clarify what the precise causal relationships might be.

Multicultural FactorsRates of schizophrenia appear to differ between racial and ethnic groups (Singh & Kunar, 2010), particularly between African Americans and white Americans. As many as 2.1 percent of African Americans receive a diagnosis of schizophrenia, compared with 1.4 percent of white Americans (Lawson, 2008; Folsom et al., 2006). Studies also find that African American patients are more likely than white American patients to be assessed as having symptoms of hallucinations, paranoia, and suspiciousness (Mark et al., 2003; Trierweiler et al., 2000). And still other studies suggest that African Americans with schizophrenia are overrepresented in state hospitals (Lawson, 2008; Barnes, 2004). For example, in Tennessee’s state hospitals, 48 percent of those with a diagnosis of schizophrenia are African American, although only 16 percent of the state population is African American (Lawson, 2008; Barnes, 2004).

It is not clear why African Americans are more likely than white Americans to receive this diagnosis. One possibility is that African Americans are more prone to develop schizophrenia. Another is that clinicians from majority groups are unintentionally biased in their diagnoses of African Americans or misread cultural differences as symptoms of schizophrenia (Lawson, 2008; Barnes, 2004).

Yet another explanation for the difference between African Americans and white Americans may lie in the economic sphere. On average, African Americans are more likely than white Americans to be poor; when economic differences are controlled for, the prevalence rates of schizophrenia become closer for the two racial groups. Consistent with the economic explanation is the finding that Hispanic Americans, who also tend to be economically disadvantaged, appear to be much more likely to be diagnosed with schizophrenia than white Americans, although their diagnostic rate is not as high as that of African Americans (Blow et al., 2004).

How might bias by diagnosticians contribute to race-

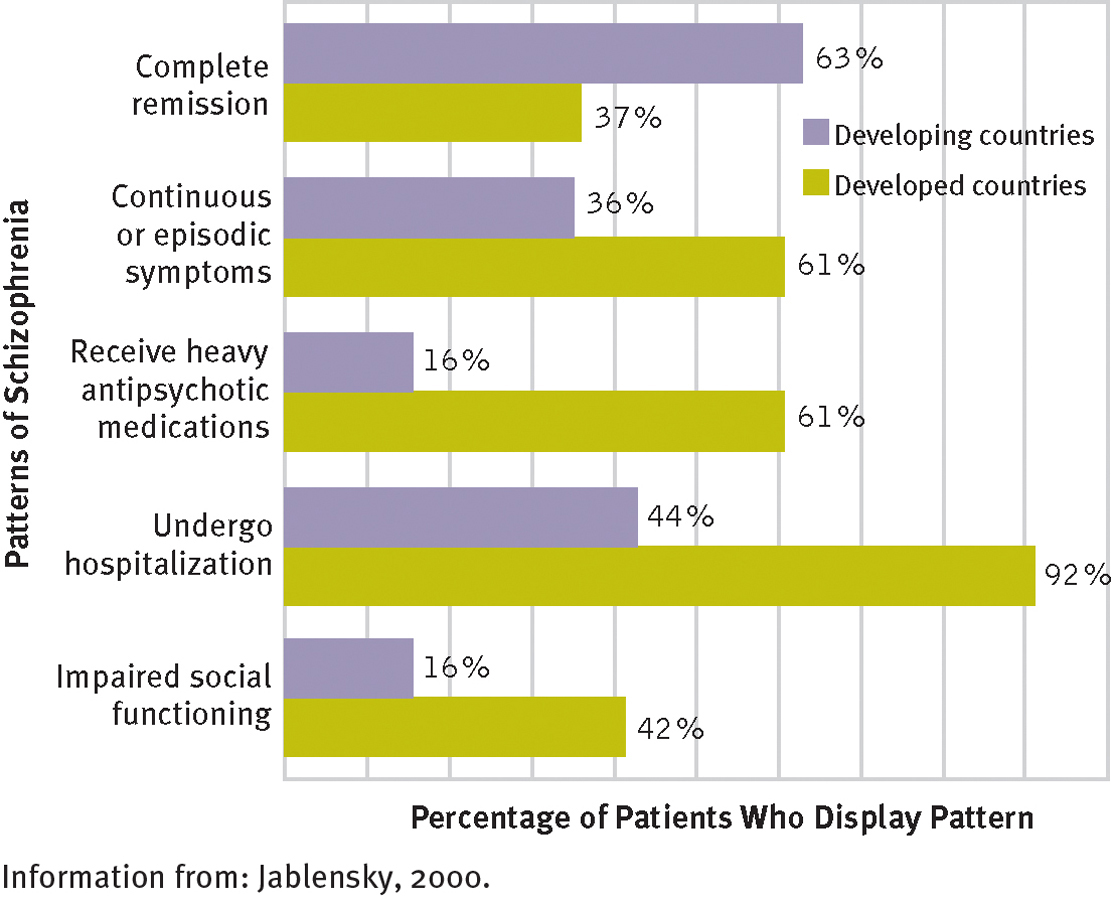

It also appears that schizophrenia differs from country to country in key ways (Johnson et al., 2014; McLean et al., 2014). Although the overall prevalence of this disorder is stable—

Do the course and outcome of schizophrenia differ from country to country?

Yes, according to a World Health Organization study. In developing countries, patients with schizophrenia seem to recover more quickly, more often, and more completely than patients in developed countries.

Some clinical theorists believe that these differences partly reflect genetic differences from population to population. However, others argue that the psychosocial environments of developing countries tend to be more supportive and therapeutic than those of developed countries, leading to more favorable outcomes for people with schizophrenia (Vahia & Vahia, 2008; Jablensky, 2000). In developing countries, for example, there may be more family and social support for people with schizophrenia; more relatives and friends available to help care for such people; and less judgmental, critical, and hostile attitudes toward people with schizophrenia. The Nigerian culture, for example, is generally more tolerant of the presence of voices than are Western cultures (Matsumoto & Juang, 2008).

BETWEEN THE LINES

Private Notions

Surveys suggest that 22 to 37 percent of people in the United States and Britain believe Earth has been visited by aliens from outer space.

Twenty percent of people worldwide believe that aliens walk on Earth disguised as humans.

(Reuters, 2010; Spanton, 2008; Andrews, 1998)

Social LabelingMany sociocultural theorists believe that the features of schizophrenia are influenced by the diagnosis itself. In their opinion, society assigns the label “schizophrenic” to people who fail to conform to certain norms of behavior. Once the label is assigned, justified or not, it becomes a self-

Like any worthwhile endeavor, becoming a schizophrenic requires a long period of rigorous training. My training for this unique calling began in earnest when I was six years old. At that time my somewhat befuddled mother took me to the University of Washington to be examined by psychiatrists in order to find out what was wrong with me. These psychiatrists told my mother: “We don’t know exactly what is wrong with your son, but whatever it is, it is very serious. We recommend that you have him committed immediately or else he will be completely psychotic within less than a year.” My mother did not have me committed since she realized that such a course of action would be extremely damaging to me. But after that ominous prophecy my parents began to view and treat me as if I were either insane or at least in the process of becoming that way. Once, when my mother caught me playing with some vile muck I had mixed up—

(Modrow, 1992, pp. 1–

Like this man, people who are labeled schizophrenic may be viewed and treated as “crazy” (Farrelly et al., 2014). Perhaps the expectations of other people subtly encourage the individuals to display psychotic behaviors (Omori, Mori, & White, 2014) and they come to accept their assigned role and learn to play it convincingly.

We have already seen the very real dangers of diagnostic labeling. In the famous Rosenhan (1973) study, discussed in Chapter 3, eight normal people presented themselves at various mental hospitals, complaining that they had been hearing voices utter the words “empty,” “hollow,” and “thud.” They were quickly diagnosed as schizophrenic, and all eight were hospitalized. Although the pseudopatients then dropped all symptoms and behaved normally, they had great difficulty getting rid of the label and gaining release from the hospital.

Rosenhan’s study is one of the most controversial in the field. What kinds of ethical, legal, and therapeutic concerns does it ralse?

The pseudopatients reported that staff members were authoritarian in their behavior toward patients, spent limited time interacting with them, and responded curtly and uncaringly to questions. They generally treated patients as though they were invisible. “A nurse unbuttoned her uniform to adjust her brassiere in the presence of an entire ward of viewing men. One did not have the sense that she was being seductive. Rather, she didn’t notice us.” In addition, the pseudopatients described feeling powerless, bored, tired, and uninterested. The deceptive design and possible implications of this study have aroused the emotions of clinicians and researchers, pro and con. The investigation does demonstrate, however, that the label “schizophrenic” can itself have a negative effect not just on how people are viewed but also on how they themselves feel and behave.

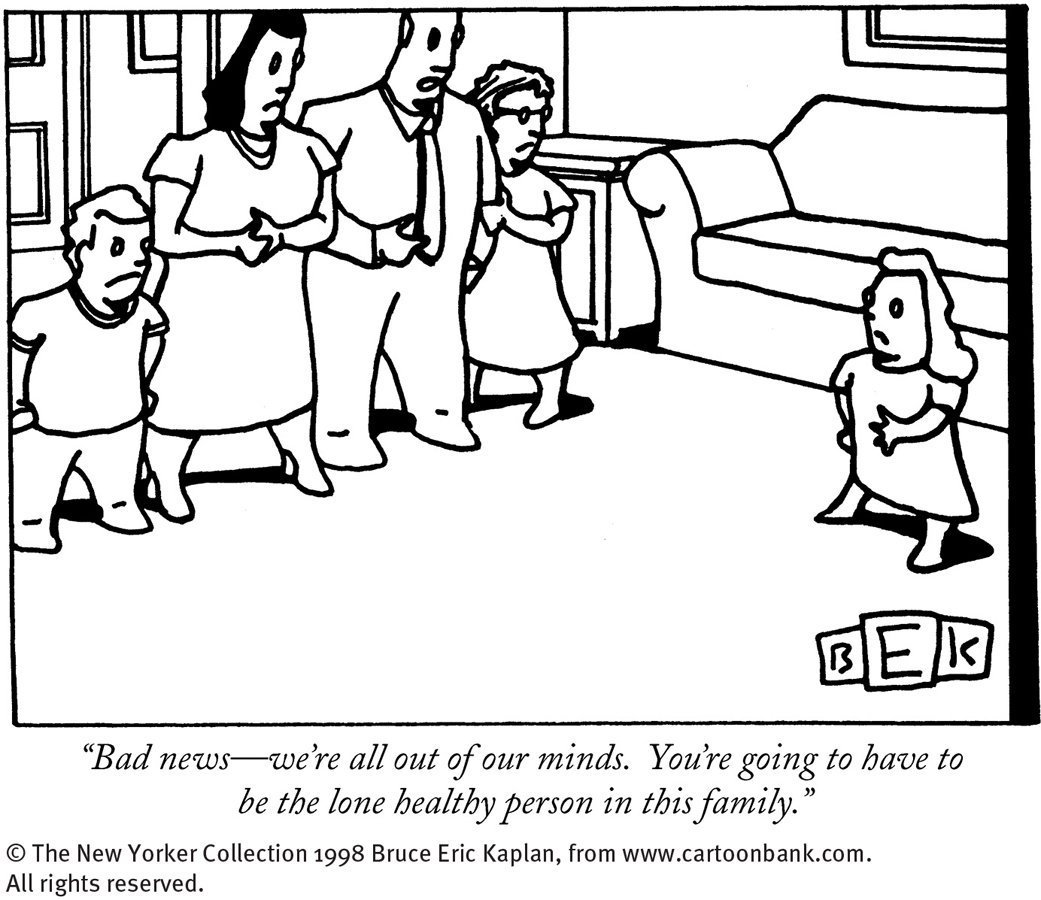

Family DysfunctioningTheorists have suggested for years that certain patterns of family interactions can promote—

DO DOUBLE-

double-bind hypothesis A theory that some parents repeatedly communicate pairs of messages that are mutually contradictory, helping to produce schizophrenia in their children.

double-bind hypothesis A theory that some parents repeatedly communicate pairs of messages that are mutually contradictory, helping to produce schizophrenia in their children.

Double-

The double-

THE ROLE OF FAMILY STRESSAlthough the double-

Family theorists have long recognized that some families are high in expressed emotion—that is, members frequently express criticism, disapproval, and hostility toward each other and intrude on one another’s privacy. People who are trying to recover from schizophrenia are almost four times more likely to relapse if they live with such a family than if they live with one low in expressed emotion (Okpokoro, Adams, & Sampson, 2014). Do such findings mean that family dysfunctioning helps cause and maintain schizophrenia? Not necessarily. It is also the case that people with schizophrenia greatly disrupt family life (Friedrich et al., 2014). In so doing, they themselves may help produce the family problems that clinicians and researchers continue to observe (Hsiao et al., 2014; McFarlane, 2011).

R. D. Laing’s ViewOne final sociocultural explanation of schizophrenia continues to have legions of supporters in the public at large despite the fact that it is controversial and largely untested by research. Famous clinical theorist R. D. Laing (1967, 1964, 1959) combined sociocultural principles with existential philosophy, arguing that schizophrenia is actually a constructive process in which people try to cure themselves of the confusion and unhappiness caused by their social environment. Laing believed that, left alone to complete this process, people with schizophrenia would indeed achieve a healthy outcome.

According to Laing’s existential principles, human beings must be in touch with their true selves in order to give meaning to their lives. Unfortunately, said Laing, this is difficult to do in present-

Most of today’s theorists reject Laing’s controversial notion that schizophrenia is constructive. For the most part, research simply has not addressed the issue. Laing’s ideas do not lend themselves to empirical research, and the existentialists who embrace his view typically have little confidence in traditional research approaches (Burston, 2000). It is also worth noting that many people with schizophrenia have themselves rejected the theory.

“Schizophrenia’s a reasonable reaction to an unreasonable society.” It’s great on paper. Poetic, noble, etc. But if you happen to be a schizophrenic, it’s got some not-

(Vonnegut, 1974, p. 91)