15.1 Institutional Care in the Past

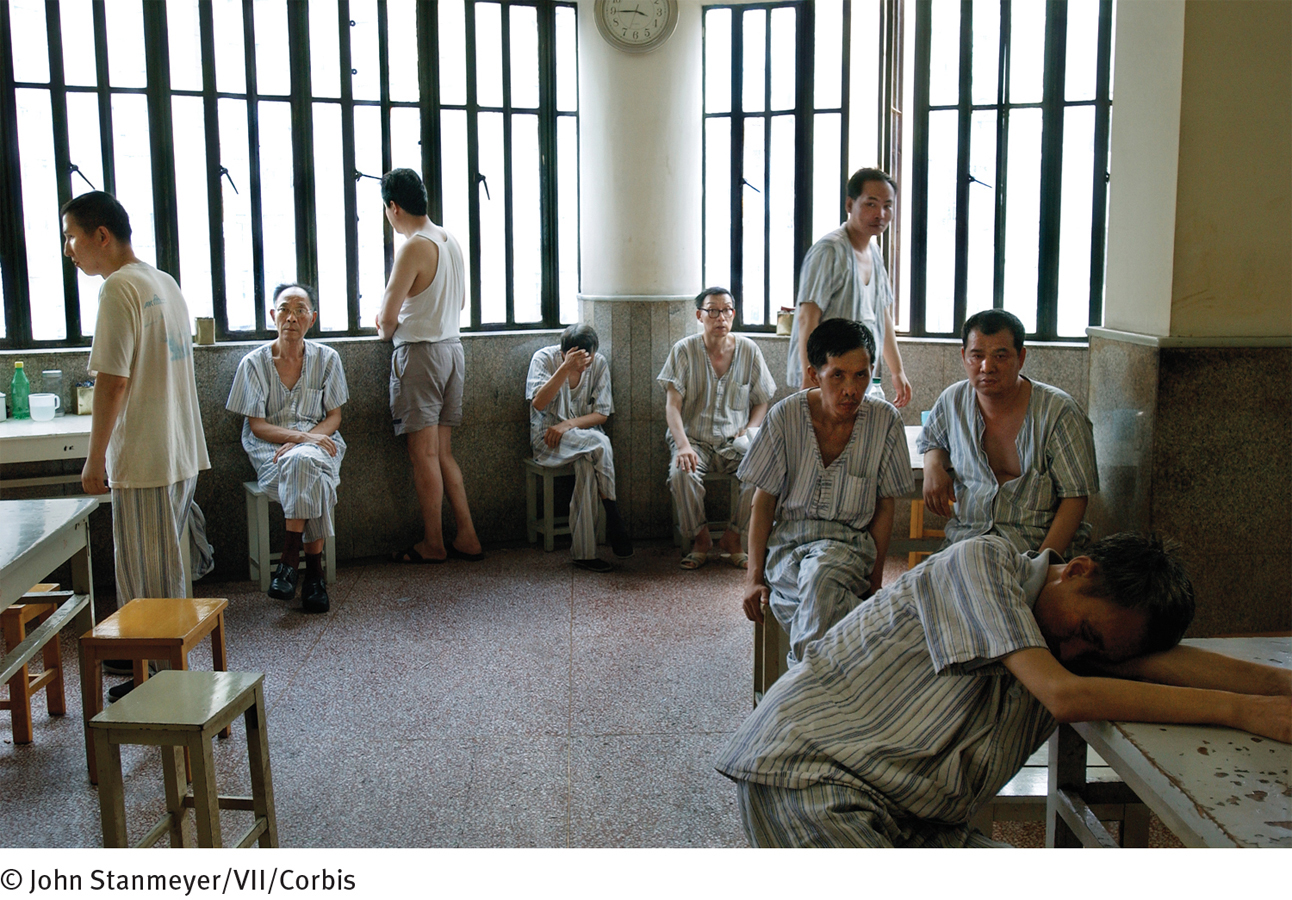

For more than half of the twentieth century, most people diagnosed with schizophrenia were institutionalized in a public mental hospital. Because patients with schizophrenia did not respond to traditional therapies, the primary goals of these hospitals were to restrain them and give them food, shelter, and clothing. Patients rarely saw therapists and generally were neglected. Many were abused. Oddly enough, this state of affairs unfolded in an atmosphere of good intentions.

As you read in Chapter 1, the move toward institutionalization in hospitals began in 1793 when French physician Philippe Pinel “unchained the insane” at La Bicêtre asylum and began the practice of “moral treatment.” For the first time in centuries, patients with severe disturbances were viewed as human beings who should be cared for with sympathy and kindness. As Pinel’s ideas spread throughout Europe and the United States, they led to the creation of large mental hospitals rather than asylums to care for those with severe mental disorders (Goshen, 1967).

These new mental hospitals, typically located in isolated areas where land and labor were cheap, were meant to protect patients from the stresses of daily life and offer them a healthful psychological environment in which they could work closely with therapists (Grob, 1966). States throughout the United States were even required by law to establish public mental institutions, state hospitals, for patients who could not afford private ones.

state hospitals Public mental hospitals in the United States, run by the individual states.

state hospitals Public mental hospitals in the United States, run by the individual states.

Eventually, however, the state hospital system encountered serious problems. Between 1845 and 1955, nearly 300 state hospitals opened in the United States, and the number of hospitalized patients on any given day rose from 2,000 in 1845 to nearly 600,000 in 1955. During this expansion, wards became overcrowded, admissions kept rising, and state funding was unable to keep up. Too many aspects of treatment became the responsibility of nurses and attendants, whose knowledge and experience at that time were limited.

Why have people with schizophrenia so often been victims of horrific treatments such as overcrowded wards, lobotomy, and, later, deinstitutionalization?

The priorities of the public mental hospitals, and the quality of care they provided, changed over those 110 years. In the face of overcrowding and understaffing, the emphasis shifted from giving humanitarian care to keeping order. In a throw-

PsychWatch

Lobotomy: How Could It Happen?

In 1935, a Portuguese neurologist named Egas Moniz performed a revolutionary new surgical procedure, which he called a prefrontal leucotomy, on a patient with severe mental dysfunctioning (Raz, 2013). The procedure, the first form of lobotomy, consisted of drilling two holes in either side of the skull and inserting an instrument resembling an icepick into the brain tissue to cut or destroy nerve fibers. Moniz believed that severe abnormal thinking—

A year after his first leucotomy, Moniz published a monograph in Europe describing his successful use of the procedure on 20 patients (Raz, 2013). An American neurologist, Walter Freeman, read the monograph, called the procedure to the attention of the medical community in the United States, performed the procedure on many patients, and became its foremost supporter. In 1947 he developed a second kind of lobotomy called the transorbital lobotomy, in which the surgeon inserted a needle into the brain through the eye socket and rotated it in order to destroy the brain tissue.

From the early 1940s through the mid-

We now know that the lobotomy was hardly a miracle treatment. Far from “curing” people with mental disorders, the procedure left thousands upon thousands extremely withdrawn, subdued, and even stuporous. Why then was the procedure so enthusiastically accepted by the medical community in the 1940s and 1950s? Neuroscientist Elliot Valenstein (1986) points first to the extreme overcrowding in mental hospitals at the time. This crowding was making it difficult to maintain decent standards in the hospitals. Valenstein also points to the personalities of the inventors of the procedure as important factors. Although these individuals were gifted and dedicated physicians—

The prestige of Moniz and Freeman were so great and the field of neurology was so small that their procedures drew little criticism. Physicians may also have been misled by the seemingly positive findings of early studies of the lobotomy, which, as it turned out, were not based on sound methodology (Cooper, 2014).

By the 1950s, better studies revealed that in addition to having a fatality rate of 1.5 to 6 percent, lobotomies could cause serious problems such as brain seizures, huge weight gain, loss of motor coordination, partial paralysis, incontinence, endocrine malfunctions, and very poor intellectual and emotional responsiveness (Lapidus et al., 2013). The discovery of effective antipsychotic drugs helped put an end to this inhumane treatment for mental disorders (Krack et al., 2010).

Today’s psychosurgical procedures are greatly refined and hardly resemble the lobotomies of 60 years back. Moreover, the procedures are considered experimental and are used only as a last resort: they are reserved for the most severe cases of disorders such as OCD and depression (Nair et al., 2014; Lapidus et al., 2013). Even so, many professionals believe that any kind of surgery that destroys brain tissue is inappropriate and perhaps unethical and that it keeps alive one of the clinical field’s most shameful and ill-

Many patients not only failed to improve under these conditions but also developed additional symptoms, apparently as a result of institutionalization itself (see InfoCentral below). The most common pattern of decline was called the social breakdown syndrome: extreme withdrawal, anger, physical aggressiveness, and loss of interest in personal appearance and functioning (Oshima et al., 2005). Often more troublesome than patients’ original symptoms, this new syndrome made it impossible for patients to return to society even if they somehow recovered from the symptoms that had first brought them to the hospital.