15.2 Institutional Care Takes a Turn for the Better

In the 1950s, clinicians developed two institutional approaches that finally brought some hope to patients who had lived in institutions for years: milieu therapy, based on humanistic principles, and the token economy program, based on behavioral principles. These approaches particularly helped improve the personal care and self-

Milieu Therapy

In the opinion of humanistic theorists, institutionalized patients deteriorate because they are deprived of opportunities to exercise independence, responsibility, and positive self-

milieu therapy A humanistic approach to institutional treatment based on the premise that institutions can help patients recover by creating a climate that promotes self-

milieu therapy A humanistic approach to institutional treatment based on the premise that institutions can help patients recover by creating a climate that promotes self-

The pioneer of this approach was Maxwell Jones, a London psychiatrist who in 1953 converted a ward of patients with various psychological disorders into a therapeutic community. The patients were referred to as “residents” and were regarded as capable of running their own lives and making their own decisions. They participated in community government, working with staff members to establish rules and determine sanctions. Residents and staff members alike were valued as important therapeutic agents. The atmosphere was one of mutual respect, support, and openness. Patients could also take on special projects, jobs, and recreational activities. In short, their daily schedule was designed to resemble life outside the hospital.

Milieu-

BETWEEN THE LINES

In Their Words

“I believe that if you grabbed the nearest normal person off the street and put them in a psychiatric hospital, they’d be diagnosable as mad within weeks.”

Clare Allan, novelist, Poppy Shakespeare

Research over the years has shown that people with schizophrenia and other severe mental disorders in milieu hospital programs often improve and that they leave the hospital at higher rates than patients in programs offering primarily custodial care (Paul, 2000; Paul & Lentz, 1977). Many remain impaired, however, and must live in sheltered settings after their release. Despite its limitations, milieu therapy continues to be practiced in many institutions, often combined with other hospital approaches (Günter, 2005). Moreover, you will see later in this chapter that many of today’s halfway houses and other community programs for people with severe mental disorders are run in accordance with the same principles of resident self-

InfoCentral

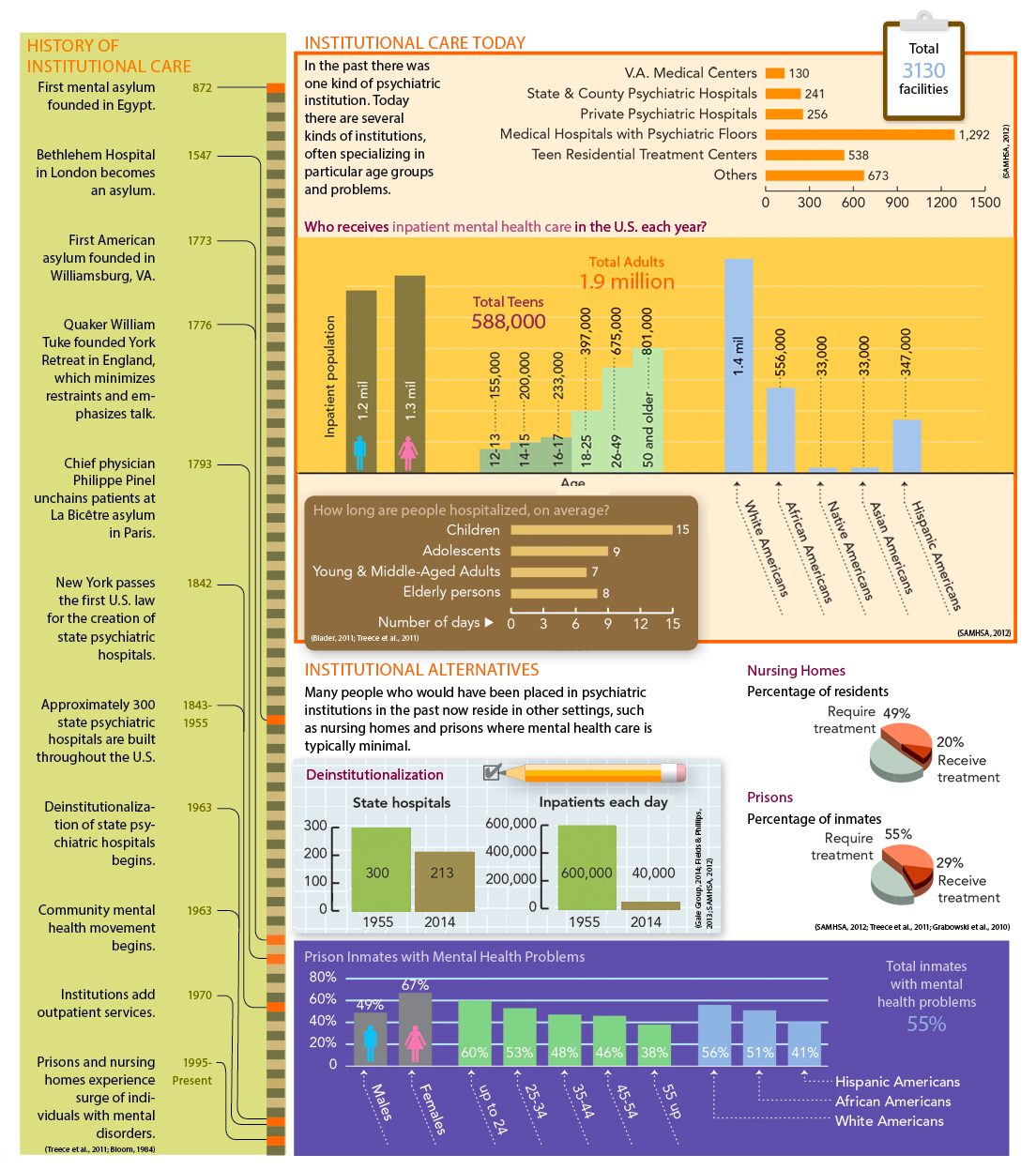

INSTITUTIONS FOR PSYCHOLOGICAL CARE

Prior to the 1960s, most people with severe mental disorders resided in institutions until they improved. Sadly, many were never released. Today, a much smaller number of people are institutionalized. Moreover, the nature and patient census of psychiatric institutionalization has changed significantly over the past 50 years.

The Token Economy

In the 1950s, behaviorists had little status in mental institutions and were permitted to work only with patients whose problems seemed hopeless. Among the “hopeless” were patients diagnosed with schizophrenia. Through years of experimentation, behaviorists discovered that the systematic use of operant conditioning techniques on hospital wards could help change the behaviors of these patients (Ayllon, 1963; Ayllon & Michael, 1959). Programs that apply these techniques are called token economy programs.

token economy program A behavioral program in which a person’s desirable behaviors are reinforced systematically throughout the day by the awarding of tokens that can be exchanged for goods or privileges.

token economy program A behavioral program in which a person’s desirable behaviors are reinforced systematically throughout the day by the awarding of tokens that can be exchanged for goods or privileges.

In token economies, patients are rewarded when they behave acceptably and are not rewarded when they behave unacceptably. The immediate rewards for acceptable behavior are often tokens that can later be exchanged for food, cigarettes, hospital privileges, and other desirable items, all of which compose a “token economy.” Acceptable behaviors likely to be included are caring for oneself and for one’s possessions (making the bed, getting dressed), going to a work program, speaking normally, following ward rules, and showing self-

How Effective Are Token Economy Programs?Researchers have found that token economies do help reduce psychotic and related behaviors (Swartz et al., 2012; Dickerson et al., 2005). In one early program, Gordon Paul and Robert Lentz (1977) set up a hospital token economy for 28 patients diagnosed with chronic schizophrenia, most of whom improved greatly. After four and a half years, 98 percent of the patients had been released, mostly to sheltered-

What Are the Limitations of Token Economies?Some clinicians have voiced reservations about the claims made regarding token economy programs. One problem is that many token economy studies, unlike Paul and Lentz’s, are uncontrolled. When administrators set up a token economy, they usually bring all ward patients into the program rather than dividing the ward into a token economy group and a control group. As a result, patients’ improvements can be compared only with their own past behaviors—

Many clinicians have also raised ethical and legal concerns. If token economy programs are to be effective, administrators need to control the important rewards in a patient’s life, perhaps including such basic ones as food and a comfortable bed. But aren’t there some things in life to which all human beings are entitled? Court decisions have now ruled that patients do indeed have certain basic rights that clinicians cannot violate, regardless of the positive goals of a treatment program. They have a right to food, storage space, and furniture, as well as freedom of movement.

Still other clinicians have questioned the quality of the improvements made under token economy programs. Are behaviorists changing a patient’s psychotic thoughts and perceptions or simply improving the patient’s ability to imitate normal behavior? This issue is illustrated by the case of a middle-

BETWEEN THE LINES

Voice in the Wilderness

Suffering from delusions, a businessman named Clifford Beers spent two years in mental institutions during the early 1900s. His later description of conditions there in an autobiography, A Mind That Found Itself, spurred a widespread reform movement in the United States, called the “mental hygiene movement,” which led to some key improvements in hospital conditions.

BETWEEN THE LINES

In Their Words

“Men will always be mad and those who think they can cure them are the maddest of all.”

Voltaire (1694–

We’re tired of it. Every damn time we want a cigarette, we have to go through their bullshit. “What’s your name? … Who wants the cigarette? … Where is the government?” Today, we were desperate for a smoke and went to Simpson, the damn nurse, and she made us do her bidding. “Tell me your name if you want a cigarette. What’s your name?” Of course, we said, “John.” We needed the cigarettes. If we told her the truth, no cigarettes. But we don’t have time for this nonsense. We’ve got business to do, international business, laws to change, people to recruit. And these people keep playing their games.

(Comer, 1973)

Critics of the behavioral approach would argue that John was still delusional and therefore as psychotic as before. Behaviorists, however, would argue that at the very least, John’s judgment about the consequences of his behavior had improved. Learning to keep his delusion to himself might even be a step toward changing his private thinking.

Last, it has often been difficult for patients to make a satisfactory transition from hospital token economy programs to community living. In an environment where rewards are contingent on proper conduct, proper conduct becomes contingent on continued rewards. Some patients who find that the real world doesn’t reward them so concretely abandon their newly acquired behaviors.

Nevertheless, token economies have had a most important effect on the treatment of people with schizophrenia and other severe mental disorders. They were among the first hospital treatments that actually changed psychotic symptoms and got chronic patients moving again. These programs are no longer as popular as they once were, but they are still used in many mental hospitals, usually along with medication, and in many community residences as well (Kopelowicz, Liberman, & Zarate, 2008). The approach has also been applied to other clinical problems, including intellectual developmental disorder, delinquency, and hyperactivity, as well as in other fields, such as education and business (Spiegler & Guevremont, 2003).