16.5 Are There Better Ways to Classify Personality Disorders?

Most of today’s clinicians believe that personality disorders represent important and troubling patterns. Yet, as you read at the beginning of this chapter, DSM-

Some of the criteria used to diagnose the DSM-

5 personality disorders cannot be observed directly. To separate paranoid from schizoid personality disorder, for example, clinicians must ask not only whether people avoid forming close relationships, but also why. In other words, the diagnoses often rely heavily on the impressions of the individual clinician. Clinicians differ widely in their judgments about when a normal personality style crosses the line and deserves to be called a disorder. Some even believe that it is wrong ever to think of personality styles as mental disorders, however troublesome they may be.

Too close for comfort These two sisters fuss over Big Jay, a Harlequin Great Dane, after they took first place in the owner/dog look-

Too close for comfort These two sisters fuss over Big Jay, a Harlequin Great Dane, after they took first place in the owner/dog look-alike contest during Massachusetts SPCA’s Mutts ‘n Fluff ‘n Stuff Day. It is common for spouses and close friends to have similar behaviors, appearances, and personality traits, a similarity that psychologists attribute to modeling and/or self- selection, among other factors. However, such explanations tend to fall short when trying to account for the same kind of similarities between many pet owners and their pets. The personality disorders often are very similar to one another. Thus it is common for people with personality problems to meet the diagnostic criteria for several DSM-

5 personality disorders (Moore et al., 2012; Loas et al., 2011). People with quite different personalities may qualify for the same DSM-

5 personality disorder diagnosis.

In light of these problems, the leading criticism of DSM-

Which key personality dimensions should clinicians use to help identify people with personality problems? Some theorists believe that they should rely on the dimensions identified in the “Big Five” theory of personality, dimensions that have received enormous attention by personality psychologists over the years.

The “Big Five” Theory of Personality and Personality Disorders

A large body of research conducted with diverse populations consistently suggests that the basic structure of personality may consist of five “supertraits,” or factors—

Many proponents of the Big Five model have argued further that it would be best to describe all people with personality disorders as being high, low, or in between on the five supertraits and to drop the use of personality disorder categories altogether (Glover et al., 2011; Lawton et al., 2011). Thus a particular person who currently qualifies for a diagnosis of avoidant personality disorder might instead be described as displaying a high degree of neuroticism, medium degrees of agreeableness and conscientiousness, and very low degrees of extroversion and openness to new experiences. Similarly, a person currently diagnosed with narcissistic personality disorder might be described in the Big Five approach as displaying very high degrees of neuroticism and extroversion, medium degrees of conscientiousness and openness to new experiences, and a very low degree of agreeableness.

“Personality Disorder—Trait Specified”: Another Dimensional Approach

BETWEEN THE LINES

“Everyone is a moon, and has a dark side which he never shows to anybody.”

Mark Twain

The “Big Five” approach to personality disorders is currently receiving considerable study and may wind up being used in the next edition of the World Health Organization’s International Classification of Diseases (ICD), the classification system for medical and psychiatric diagnoses used in many countries outside the United States (Aldhous, 2012). In the meantime, as you read earlier, the DSM-

InfoCentral

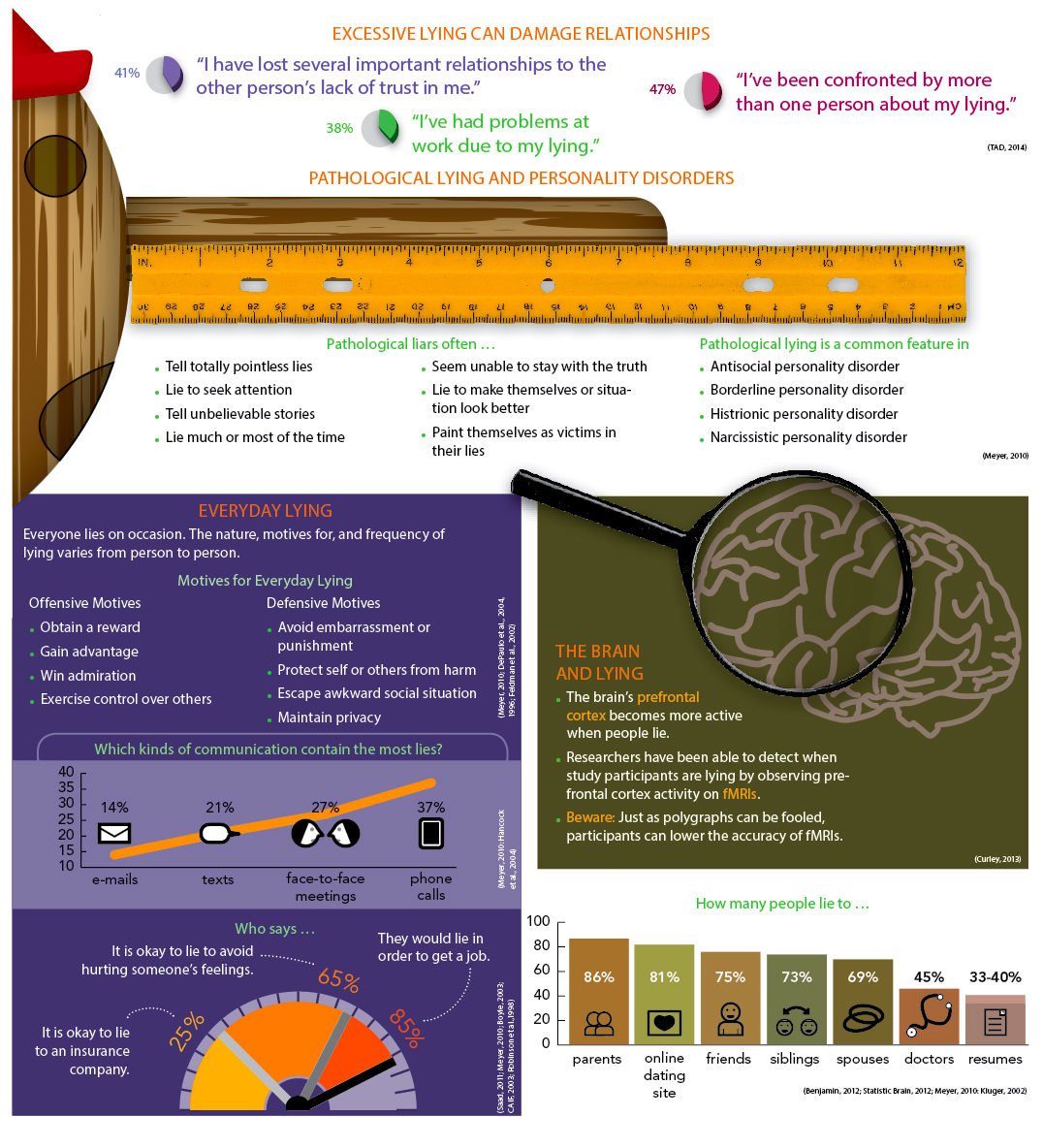

LYING

A lie is a false statement that a person makes in order to deliberately deceive another person. Everyone lies. But there is lying, and then there is “lying.” Psychologists often distinguish several kinds of lying: everyday lying, compulsive lying, and sociopathic lying. Compulsive and sociopathic lying are often referred to, collectively, as pathological lying.

Everyday liars: Almost everyone lies on occasion

Compulsive liars: Some people consistently lie out of habit, even when nothing is gained by the lies.

Sociopathic liars: Some people lie incessantly, without any concern for others, in order to get their way.

This approach begins with the notion that people whose traits significantly impair their functioning should receive a diagnosis called personality disorder—trait specified (PDTS) (APA, 2013). When assigning this diagnosis, clinicians would also identify and list the problematic traits and rate the severity of impairment caused by them. According to the proposal, five groups of problematic traits would be eligible for a diagnosis of PDTS: negative affectivity, detachment, antagonism, disinhibition, and psychoticism.

personality disorder—trait specified (PDTS) A personality disorder currently undergoing study for possible inclusion in a future revision of DSM-

personality disorder—trait specified (PDTS) A personality disorder currently undergoing study for possible inclusion in a future revision of DSM-

Negative Affectivity People who display negative affectivity experience negative emotions frequently and intensely. In particular, they exhibit one or more of the following traits: emotional lability (unstable emotions), anxiousness, separation insecurity, perseveration (repetition of certain behaviors despite repeated failures), submissiveness, hostility, depressivity, suspiciousness, and strong emotional reactions (overreactions to emotionally arousing situations).

Detachment People who manifest detachment tend to withdraw from other people and social interactions. They may exhibit any of the following traits: restricted emotional reactivity (little reaction to emotionally arousing situations), depressivity, suspiciousness, withdrawal, anhedonia (inability to feel pleasure or take interest in things), and intimacy avoidance. You’ll note that two of the traits in this group—

depressivity and suspiciousness— are also found in the negative affectivity group. Antagonism People who display antagonism behave in ways that put them at odds with other people. They may exhibit any of the following traits (including hostility, which is also found in the negative affectivity group): manipulativeness, deceitfulness, grandiosity, attention seeking, callousness, and hostility.

Disinhibition People who manifest disinhibition behave impulsively, without reflecting on potential future consequences. They may exhibit any of the following traits: irresponsibility, impulsivity, distractibility, risk taking, and imperfection/disorganization.

Psychoticism People who display psychoticism have unusual and bizarre experiences. They may exhibit any of the following traits: unusual beliefs and experiences, eccentricity, and cognitive and perceptual dysregulation (odd thought processes and sensory experiences).

If a person is impaired significantly by any of the five trait groups, or even by just 1 of the 25 traits that make up those groups, he or she would qualify for a diagnosis of personality disorder—

Consider, for example, Matthew, the unhappy 34-

According to this dimensional approach, when clinicians assign a diagnosis of personality disorder—

Consider Matthew once again. He would probably warrant a rating of “0” on most of the 25 traits listed in the DSM-

Diagnosis: Personality Disorder—

Separation insecurity: Rating 4

Submissiveness: Rating 4

Anxiousness: Rating 3

Depressivity: Rating 3

Other traits: Rating 0

This dimensional approach to personality disorders may indeed prove superior to DSM-