17.3 Depressive and Bipolar Disorders

Like Billy, the boy you read about at the beginning of this chapter, around 2 percent of children and 8 percent of adolescents currently experience a major depressive disorder (Mash & Wolfe, 2012). As many as 20 percent of adolescents experience at least one depressive episode during their teen years. In addition, many clinicians believe that children may experience bipolar disorder.

Major Depressive Disorder

As with anxiety disorders, very young children lack some of the cognitive skills that help produce clinical depression, thus accounting for the low rate of depression among the very young (Hankin et al., 2008). For example, in order to experience the sense of hopelessness typically found in depressed adults, children must be able to hold expectations about the future, a skill rarely in full bloom before the age of 7.

Nevertheless, if life situations or biological predispositions are significant enough, even very young children sometimes have severe downward turns of mood (Tang et al., 2014; Swearer et al., 2011). Depression in the young may be triggered by negative life events (particularly losses), major changes, rejection, or ongoing abuse. Childhood depression is commonly characterized by such symptoms as headaches, stomach pain, irritability, and a disinterest in toys and games (Schulte & Petermann, 2011).

Clinical depression is much more common among teenagers than among young children. Adolescence is, under the best of circumstances, a difficult and confusing time, marked by angst, hormonal and bodily changes, mood changes, complex relationships, and new explorations (see MindTech below). For some teens, these “normal” upsets of adolescence cross the line into clinical depression. As you read in Chapter 9, suicidal thoughts and attempts are particularly common among adolescents—

Interestingly, while there is no difference between the rates of depression in boys and girls before the age of 13, girls are twice as likely as boys to be depressed by the age of 16 (Naninck et al., 2011; Merikangas et al., 2010; Hankin et al., 2008). Why this gender shift? Several factors have been suggested, including hormonal changes, the fact that females increasingly experience more stressors than males, and the tendency of girls to become more emotionally invested than boys in social and intimate relationships as they mature. One explanation also focuses on teenage girls’ growing dissatisfaction with their bodies. Whereas boys tend to like the increase in muscle mass and other body changes that accompany puberty, girls often detest the increases in body fat and weight gain that they experience during puberty and beyond. Raised in a society that values and demands extreme thinness as the aesthetic female ideal, many adolescent girls feel imprisoned by their own bodies, have low self-

For years, it was generally believed that childhood and teenage depression would respond well to the same treatments that have been of help to depressed adults—

In one development, the National Institute of Mental Health recently sponsored a massive six-

MindTech

Parent Anxiety on the Rise

Parents have always worried about their children—

What exactly do parents worry about when their children go online, and who is worrying the most? Researchers Danah Boyd and Eszter Hargittai (2013) surveyed more than 1,000 parents across the United States and found that safety is at the heart of parents’ anxiety. Almost two-

As you might expect, these areas of anxiety were not distributed evenly among parents. African American, Hispanic American, and Asian American parents were much more likely than white American parents to have these concerns. Urban parents were more fearful than suburban and rural parents. Lower-

Mothers expressed more fear than fathers about their children being bullied online. Parents of daughters were more concerned than parents of sons about their children meeting harmful strangers and being exposed to violence online. And politically conservative and moderate parents expressed significantly more anxiety than liberal parents about their children viewing pornography or meeting strangers online.

Given teens’ ever-

In the early days of the Internet, parents would address concerns of this kind by supervising and restricting their children’s online time and access. But those “good old days” are now gone and such solutions have become less and less available, given the increasing number of U.S. teens who own a smartphone (now, almost half of them) and the easy access teens have to computers and tablets in so many locations outside the home (Fondas, 2014). In turn, parental anxiety continues to rise. ![]()

BETWEEN THE LINES

In Their Words

“The boy will come to nothing.”

Jakob Freud, 1864 (referring to his 8-

A second development in recent years has been the discovery that antidepressant drugs may be very dangerous for some depressed children and teenagers. Throughout the 1990s, most psychiatrists believed that second-

Arguments about the wisdom of this FDA order have since ensued. Although most clinicians agree that the drugs may increase the risk of suicidal thoughts and attempts in as many as 2 to 4 percent of young patients, some have noted that the overall risk of suicide may actually be reduced for the vast majority of children who take the drugs (Isacsson & Rich, 2014; Vela et al., 2011). They point out, for example, that suicides among children and teenagers decreased by 30 percent in the decade leading up to 2004, as the number of antidepressant prescriptions provided to children and teenagers were soaring.

While the findings of the TADS study and questions about antidepressant drug safety continue to be sorted out, these two developments serve to highlight once again the importance of research, particularly in the treatment realm. We are reminded that treatments that work for individuals of a certain age, gender, race, or ethnic background may be ineffective or even dangerous for other groups of people.

Bipolar Disorder and Disruptive Mood Dysregulation Disorder

For decades, bipolar disorder was thought to be exclusively an adult disorder, and that its earliest age of onset is the late teens (APA, 2013). However, since the mid-

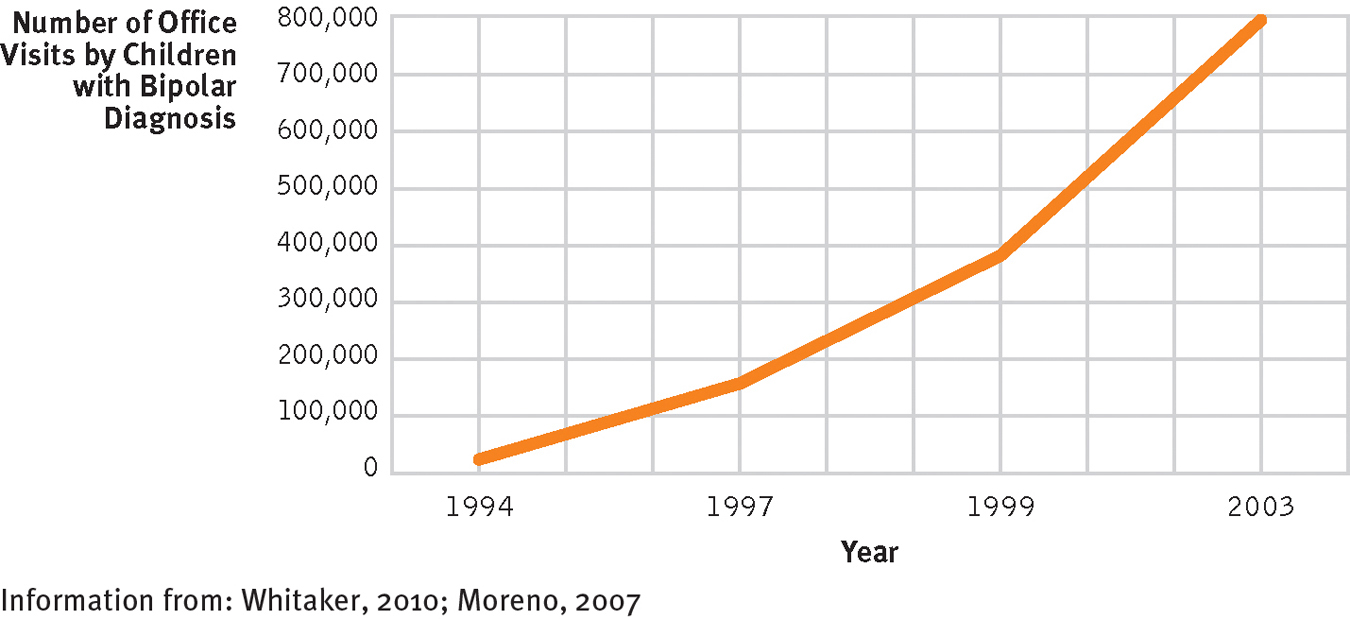

Rapid rise: Children and bipolar disorder

The number of private office visits for children and teenagers with a diagnosis of bipolar disorder rose from 20,000 in 1994 to 800,000 in 2003.

Most theorists believe that these numbers reflect not an increase in the prevalence of bipolar disorders among children but rather a new diagnostic trend. The question is whether this trend is accurate. In a national survey of adults with bipolar disorders, 33 percent of the respondents recalled that their symptoms actually began before they reached 15 years of age, and another 27 percent said their symptoms first appeared between the ages of 15 and 19 (Hirschfeld et al., 2003). Such responses indicate that bipolar disorders among children and teenagers have indeed been around for years but were overlooked by diagnosticians and therapists.

Some clinical theorists, however, distrust the accuracy of such retrospective reports and believe that the diagnosis of bipolar disorder is currently being overapplied to children and adolescents (Paris, 2014; Mash & Wolfe, 2012). They suggest that the label has become a clinical catchall that is being applied to almost every explosive, aggressive child. In fact, symptoms of rage and aggression, along with depression, dominate the clinical picture of most children who have received a bipolar diagnosis over the past two decades (Roy et al., 2013; Diler et al., 2010). The children may not even manifest the symptoms of mania or the mood swings that characterize adult bipolar disorder. Moreover, two-

The DSM-

disruptive mood dysregulation disorder A childhood disorder marked by severe recurrent temper outbursts along with a persistent irritable or angry mood.

disruptive mood dysregulation disorder A childhood disorder marked by severe recurrent temper outbursts along with a persistent irritable or angry mood.

|

Disruptive Mood Dysregulation Disorder |

|

|---|---|

|

1. |

For at least a year, individual repeatedly displays severe outbursts of temper that are extremely out of proportion to triggering situations and different from ones displayed by most other people of his or her age. |

|

2. |

The outbursts occur at least three times per week and are present in at least two settings (home, school, with peers). |

|

3. |

Individual repeatedly displays irritable or angry mood between the outbursts. |

|

4. |

Individual receives initial diagnosis between 6 and 18 years of age. |

|

(Information from: APA, 2013) |

|

This issue is particularly important because the rise in diagnoses of bipolar disorder has been accompanied by an increase in the number of children who are prescribed adult medications (Toteja et al., 2014; Chang et al., 2010; Grier et al., 2010). Around one-