17.4 Oppositional Defiant Disorder and Conduct Disorder

Most children break rules or misbehave on occasion. If they consistently display extreme hostility and defiance, however, they may qualify for a diagnosis of oppositional defiant disorder or conduct disorder. Those with oppositional defiant disorder are argumentative and defiant, angry, and irritable, and in some cases, vindictive (APA, 2013). They may argue repeatedly with adults, ignore adult rules and requests, deliberately annoy other people, and feel much anger and resentment. As many as 10 percent of children qualify for a diagnosis of oppositional defiant disorder (Mash & Wolfe, 2012; Merikangas et al., 2010). The disorder is more common in boys than in girls before puberty but equal in both sexes after puberty.

oppositional defiant disorder A childhood disorder in which children are repeatedly argumentative and defiant, angry and irritable, and in some cases, vindictive.

oppositional defiant disorder A childhood disorder in which children are repeatedly argumentative and defiant, angry and irritable, and in some cases, vindictive.

Children with conduct disorder, a more severe problem, repeatedly violate the basic rights of others (APA, 2013). They are often aggressive and may be physically cruel to people or animals, deliberately destroy other people’s property, steal or lie, skip school, or run away from home (see Table 17-3). Many threaten or harm their victims, committing such crimes as firesetting, shoplifting, forgery, breaking into buildings or cars, mugging, and armed robbery. As they get older, their acts of physical violence may include rape or, in rare cases, homicide. The symptoms of conduct disorder are apparent in this summary of a clinical interview with a 15-

BETWEEN THE LINES

Underlying Problems

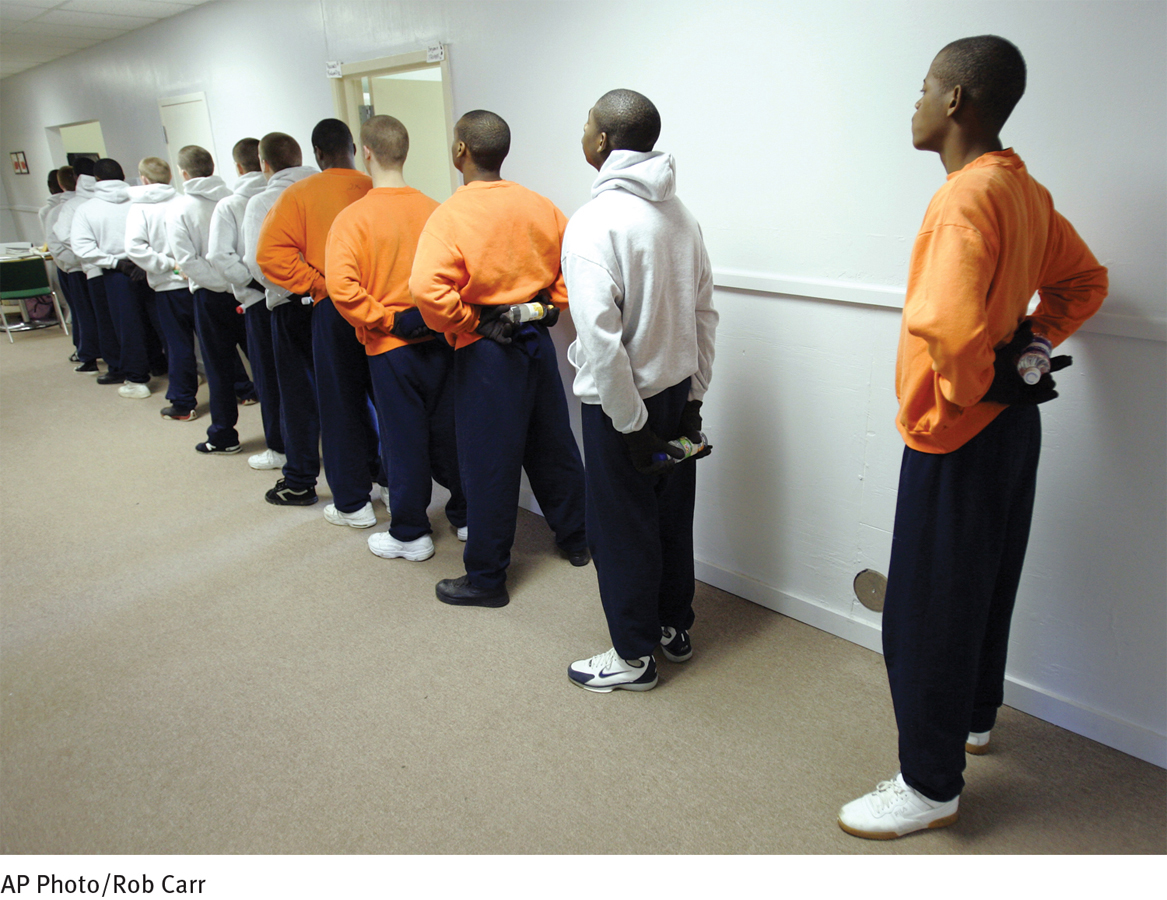

There are approximately 110,000 teenagers in the United States incarcerated each year. Three-

(Nordal, 2010)

conduct disorder A childhood disorder in which the child repeatedly violates the basic rights of others and displays aggression, characterized by symptoms such as physical cruelty to people or animals, the deliberate destruction of other people’s property, and the commission of various crimes.

conduct disorder A childhood disorder in which the child repeatedly violates the basic rights of others and displays aggression, characterized by symptoms such as physical cruelty to people or animals, the deliberate destruction of other people’s property, and the commission of various crimes.

Questioning revealed that Derek was getting into … serious trouble of late, having been arrested for shoplifting 4 weeks before. Derek was caught with one other youth when he and a dozen friends swarmed a convenience store and took everything they could before leaving in cars. This event followed similar others at [an electronics] store and a … clothing store. Derek blamed his friends for his arrest because they apparently left him behind as he straggled out of the store. He was charged only with shoplifting, however, after police found him holding just three candy bars and a bag of potato chips. Derek expressed no remorse for the theft or any care for the store clerk who was injured when one of the teens pushed her into a glass case. When informed of the clerk’s injury, for example, Derek replied, “I didn’t do it, so what do I care?”

The psychologist questioned Derek further about other legal violations and discovered a rather extended history of trouble. Derek was arrested for vandalism 10 months earlier for breaking windows and damaging cars on school property. He received probation for 6 months because this was his first offense. Derek also boasted of other exploits for which he was not caught, including several shoplifting episodes, … joyriding, and missing school. Derek missed 23 days (50 percent) of school since the beginning of the academic year. In addition, he described break-

(Kearney, 2013, pp. 87–

|

Conduct Disorder |

|

|---|---|

|

1. |

Individual repeatedly behaves in ways that violate the rights of other people or ignore the norms or rules society, beyond the violations displayed by most other people of his or her age. |

|

2. |

At least three of the following features are present over the past year (and at least one in the past 6 months): • Frequent bullying or threatening of others • Frequent provoking of physical fights • Using dangerous weapons • Physical cruelty to people • Physical cruelty to animals • Stealing during confrontations with a victim • Forcing someone into sexual activity • Fire- |

|

3. |

Significant impairment. |

|

(Information from: APA, 2013) |

|

Conduct disorder usually begins between 7 and 15 years of age (APA, 2013). As many as 10 percent of children, three-

Some clinical theorists believe that there are actually several kinds of conduct disorder, including (1) the overt-

Other researchers distinguish yet another pattern of aggression found in certain cases of conduct disorder, relational aggression, in which the individual is socially isolated and primarily engages in social misdeeds such as slandering others, spreading rumors, and manipulating friendships (Ostrov et al., 2014; Keenan et al., 2010) (see MediaSpeak below). Relational aggression is more common among girls than boys.

Many children with conduct disorder are suspended from school, placed in foster homes, or incarcerated (Weyandt et al., 2011). When children between the ages of 8 and 18 break the law, the legal system often labels them juvenile delinquents (Wiklund et al., 2014; Jiron, 2010). More than half of the juveniles who are arrested each year are recidivists, meaning they have a history of having been arrested. Boys are much more involved in juvenile crime than girls, although the gap between them is narrowing. Girls are most likely to be arrested for drug use, sexual offenses, and running away, boys for drug use and crimes against property. After steadily rising during the 1990s, the number of arrests of teenagers for serious crimes has fallen by one-

MediaSpeak

Targeted for Bullying

By Jesse McKinley, The New York Times, October 4, 2010

When Seth Walsh was in the sixth grade, he turned to his mother one day and told her he had something to say. “I was folding clothes, and he said, ‘Mom, I’m gay,’” said Wendy Walsh, a hairstylist and single mother of four. “I said, ‘O.K., sweetheart, I love you no matter what.’"

But last month, Seth went into the backyard of his home in the desert town of Tehachapi, Calif., and hanged himself, apparently unable to bear a relentless barrage of taunting, bullying and other abuse at the hands of his peers. After a little more than a week on life support, he died last Tuesday. He was 13.

The case of Tyler Clementi, the Rutgers University freshman who jumped off the George Washington Bridge after a sexual encounter with another man was broadcast online, has shocked many. But his death is just one of several suicides in recent weeks by young gay teenagers who had been harassed by classmates, both in person and online.

The list includes Billy Lucas, a 15-

Less than two weeks later, Asher Brown, a 13-

The deaths have set off an impassioned—

“This is a moment where every one of us—

According to a recent survey, … nearly 9 of 10 gay, lesbian, transgender or bisexual middle and high school students suffered physical or verbal harassment in 2009, ranging from taunts to outright beatings….

In a pair of blog postings last week, Dan Savage, a sex columnist based in Seattle, assigns the blame to negligent teachers and school administrators, bullying classmates and “hate groups that warp some young minds and torment others.” …

“There are accomplices out there,” he wrote Saturday….

In late September, Mr. Savage began a project on YouTube called “It Gets Better,” featuring gay adults talking about their experiences with harassment as adolescents….

Can you suggest approaches, in addition to “It Gets Better,” that might help reduce address the problem of bullying, particularly bullying of LGBT people?

In Tehachapi, in Kern County south of here, more than 500 mourners attended a memorial on Friday for Seth Walsh. One of those … a classmate and friend, said Seth had long known he was gay and had been teased for years. “But this year it got much worse,” Jamie said. “People would say, ‘You should kill yourself,’ ‘You should go away,’ ‘You’re gay, who cares about you?’” …

For her part, Ms. Walsh said she … did not want to cast blame, though she hoped his death would teach people “not to discriminate, not be prejudiced.”

“I truly hope,” she said, “that people understand that.”

October 4, 2010, “Several Recent Suicides Put Light on Pressures Facing Gay Teenagers” by Jesse McKinley. From The New York Times, 10/4/2010, © 2010 The New York Times. All rights reserved. Used by permission and protected by the copyright laws of the United States. The printing, copying, redistribution, or retransmission of this content without express written permission is prohibited.

What Are the Causes of Conduct Disorder?

BETWEEN THE LINES

Narrowing the Gender Gap

Today, one of every three teens arrested for violent crimes is female.

(Department of Justice, 2008; Scelfo, 2005)

Many cases of conduct disorder, particularly those marked by destructive behaviors, have been linked to genetic and biological factors (Kerekes et al., 2014; Wallace et al., 2014). In addition, a number of cases have been tied to drug abuse, poverty, traumatic events, and exposure to violent peers or community violence (Wymbs et al., 2014; Weyandt et al., 2011). Most often, however, conduct disorder has been tied to troubled parent–

How Do Clinicians Treat Conduct Disorder?

Because aggressive behaviors become more locked in with age, treatments for conduct disorder are generally most effective with children younger than 13 (APA, 2013; Webster-

Sociocultural TreatmentsGiven the importance of family factors in conduct disorder, therapists often use family interventions. One such approach, used with preschoolers, is called parent-

When children reach school age, therapists often use a family intervention called parent management training. In this approach, (1) parents are again taught more effective ways to deal with their children, and (2) parents and children meet together in behavior-

BETWEEN THE LINES

In Their Words

“Children nowadays are tyrants. They contradict their parents, gobble their food, and tyrannize their teachers.”

Socrates, 425 b.c.

Other sociocultural approaches, such as residential treatment in the community and programs at school, have also helped some children improve. In one such approach, treatment foster care, delinquent boys and girls with conduct disorder are assigned to a foster home in the community by the juvenile justice system (Henggeler & Sheidow, 2012). While there, the children, foster parents, and birth parents all receive training and treatment interventions, including family therapy with both sets of parents, individual treatment for the child, and meetings with the school and with parole and probation officers. In addition, the children and their parents continue to receive treatment and support after they leave foster care. This program is apparently most beneficial when all the intervention components are applied simultaneously.

In contrast to these sociocultural interventions, institutionalization in so-

How might juvenile training centers themselves contribute to the high recidivism rate among teenage criminal offenders?

Child-

In another child-

Recently, drug therapy has also been used for children with conduct disorder. Studies suggest that stimulant drugs may be helpful in reducing their aggressive behaviors at home and at school (Levy & Bloch, 2012; Connor et al., 2002).

PreventionIt may be that the best hope for dealing with the problem of conduct disorder lies in prevention programs that begin in the earliest stages of childhood (Hektner et al., 2014; Boxer & Frick, 2008). These programs try to change unfavorable social conditions before a conduct disorder is able to develop. The programs may offer training opportunities for young people, recreational facilities, and health care, and may try to ease the stresses of poverty and improve parents’ child-