17.6 Neurodevelopmental Disorders

Neurodevelopmental disorders are a group of disabilities in the functioning of the brain that emerge at birth or during very early childhood and affect the individual’s behavior, memory, concentration, and/or ability to learn. As you read at the beginning of this chapter, many of the disorders first displayed during childhood subside as the person ages. However, the neurodevelopmental disorders often have a significant impact throughout the person’s life. For example, at least half of those with attention-

neurodevelopmental disorders A group of disabilities—

neurodevelopmental disorders A group of disabilities—

Researchers have investigated each of these disorders extensively. In addition, although this was not always so, clinicians now have a range of treatment approaches that can make a major difference in the lives of people with these problems.

Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder

Children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) have great difficulty attending to tasks, or behave overactively and impulsively, or both (APA, 2013) (see Table 17-5). ADHD often appears before the child starts school, as with Ricky, one of the boys we met at the beginning of this chapter. Steven is another child whose symptoms began very early in life:

attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) A disorder marked by the inability to focus attention, or overactive and impulsive behavior, or both.

attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) A disorder marked by the inability to focus attention, or overactive and impulsive behavior, or both.

Steven’s mother cannot remember a time when her son was not into something or in trouble. As a baby he was incredibly active, so active in fact that he nearly rocked his crib apart. All the bolts and screws became loose and had to be tightened periodically. Steven was also always into forbidden places, going through the medicine cabinet or under the kitchen sink. He once swallowed some washing detergent and had to be taken to the emergency room. As a matter of fact, Steven had many more accidents and was more clumsy than his older brother and younger sister…. He always seemed to be moving fast. His mother recalls that Steven progressed from the crawling stage to a running stage with very little walking in between.

Trouble really started to develop for Steven when he entered kindergarten. Since his entry into school, his life has been miserable and so has the teacher’s. Steven does not seem capable of attending to assigned tasks and following instructions. He would rather be talking to a neighbor or wandering around the room without the teacher’s permission. When he is seated and the teacher is keeping an eye on him to make sure that he works, Steven’s body still seems to be in motion. He is either tapping his pencil, fidgeting, or staring out the window and daydreaming. Steven hates kindergarten and has few long-

(Gelfand, Jenson, & Drew, 1982, p. 256)

|

Attention- |

||

|---|---|---|

|

1. |

Individual presents one or both of the following patterns: |

|

|

|

(a) |

For 6 months or more, individual frequently displays at least six of the following symptoms of inattention, to a degree that is maladaptive and beyond that shown by most similarly aged persons: • Unable to properly attend to details, or frequently makes careless errors • Finds it hard to maintain attention • Fails to listen when spoken to by others • Fails to carry out instructions and finish work • Disorganized • Dislikes or avoids mentally effortful work • Loses items that are needed for successful work • Easily distracted by irrelevant stimuli • Forgets to do many everyday activities. |

|

|

(b) |

For 6 months or more, individual frequently displays at least six of the following symptoms of hyperactivity and impulsivity, to a degree that is maladaptive and beyond that shown by most similarly aged persons: • Fidgets, taps hands or feet, or squirms • Inappropriately wanders from seat • Inappropriately runs or climbs • Unable to play quietly • In constant motion • Talks excessively • Interrupts questioners during discussions• Unable to wait for turn • Barges in on others’ activities or conversations. |

|

2. |

Individual displayed some of the symptoms before 12 years of age. |

|

|

3. |

Individual shows symptoms in more than one setting. |

|

|

4. |

Individual experiences impaired functioning. |

|

|

(Information from: APA, 2013.) |

||

BETWEEN THE LINES

ADHD and School

More than 90 percent of children with ADHD underachieve scholastically. On average, they have more failing grades and lower grade point averages than other children.

Students with ADHD are more likely than other children to be retained, suspended, or expelled from school.

Between 23 and 32 percent of children with ADHD do not complete high school.

Twenty-

two percent of people with ADHD are admitted to college.

(Rapport et al., 2008)

The symptoms of ADHD often feed into one another. Children who have trouble focusing attention may keep turning from task to task until they end up trying to run in several directions at once. Similarly, children who move constantly may find it hard to attend to tasks or show good judgment. In many cases, one of these symptoms stands out much more than the other. About half of the children with ADHD also have learning or communication problems; many perform poorly in school; a number have difficulty interacting with other children, and about 80 percent misbehave, often quite seriously (Mash & Wolfe, 2012;Goldstein, 2011). It is also common for these children to have anxiety or mood problems (Advokat et al., 2014; Günther et al., 2011).

Around 5 percent of all children display ADHD at any given time, as many as 70 percent of them boys (APA, 2013; Merikangas et al., 2011). Those whose parents have had ADHD are more likely than others to develop it. The disorder usually persists throughout childhood. Many children show a marked lessening of symptoms as they move into mid-

ADHD is a difficult disorder to assess properly (Batstra et al., 2014). Ideally, the child’s behavior should be observed in several environments (school, home, with friends) because the symptoms of hyperactivity and inattentiveness must be present across multiple settings in order for ADHD to be diagnosed (Burns et al., 2014; APA, 2013). Because children with ADHD often give poor descriptions of their symptoms, it is important to obtain reports of the child’s symptoms from his or her parents and teachers. And, finally, although diagnostic interviews, ratings scales, and psychological tests can be helpful in the assessment of ADHD (DuPaul & Kern, 2011), studies suggest that many children receive their diagnosis from pediatricians or family physicians rather than mental health professionals and that at most one-

What Are the Causes of ADHD?Today’s clinicians generally consider ADHD to have several interacting causes. Biological factors have been identified in many cases, particularly abnormal activity of the neurotransmitter dopamine and abnormalities in the frontal-

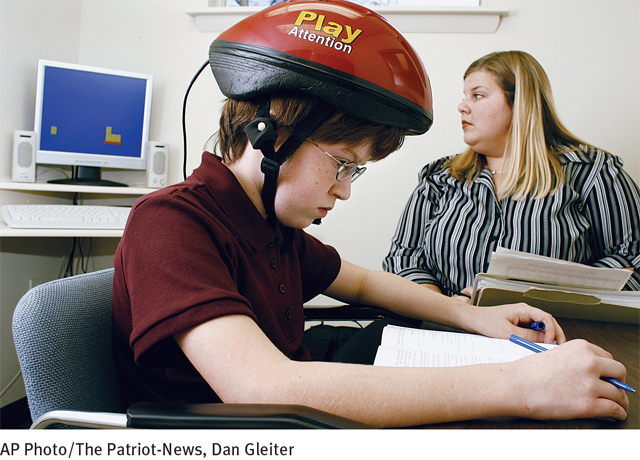

How Is ADHD Treated?Almost 80 percent of all children and adolescents with ADHD receive treatment (Winter & Bienvenu, 2011). There is, however, disagreement in the field about which kind of treatment is most effective. The most commonly used approaches are drug therapy, behavioral therapy, or a combination of the two (Sibley et al., 2014).

DRUG THERAPYLike Tom, the child described in the following case, millions of children and adults with ADHD are currently treated with methylphenidate, a stimulant drug that actually has been available for decades, or with certain other stimulants.

methylphenidate A stimulant drug, known better by the trade name Ritalin, commonly used to treat ADHD.

methylphenidate A stimulant drug, known better by the trade name Ritalin, commonly used to treat ADHD.

When Tom was born, he acted like a “crack baby,” his mother, Ann, says. “He responded violently to even the slightest touch, and he never slept.” Shortly after Tom turned two, the … day care center asked Ann to withdraw him. They deemed his behavior “just too aberrant,” she remembers. Tom’s doctors ran a battery of tests to screen for brain damage, but they found no physical explanation for his lack of self-

(Leutwyler, 1996, p. 13)

Although a variety of manufacturers now produce methylphenidate, the drug continues to be known to the public by its most famous trade name, Ritalin. As researchers have confirmed Ritalin’s quieting effect on children with ADHD and its ability to help them focus, solve complex tasks, perform better at school, and control aggression, use of the drug has increased enormously—

It is estimated that 2.2 million children in the United States, 3 percent of all schoolchildren, regularly take Ritalin or other stimulant drugs for ADHD (Mash & Wolfe, 2012). Collectively, the stimulant drugs are now the most common treatment for the disorder. Many clinicians, though, worry about the possible long-

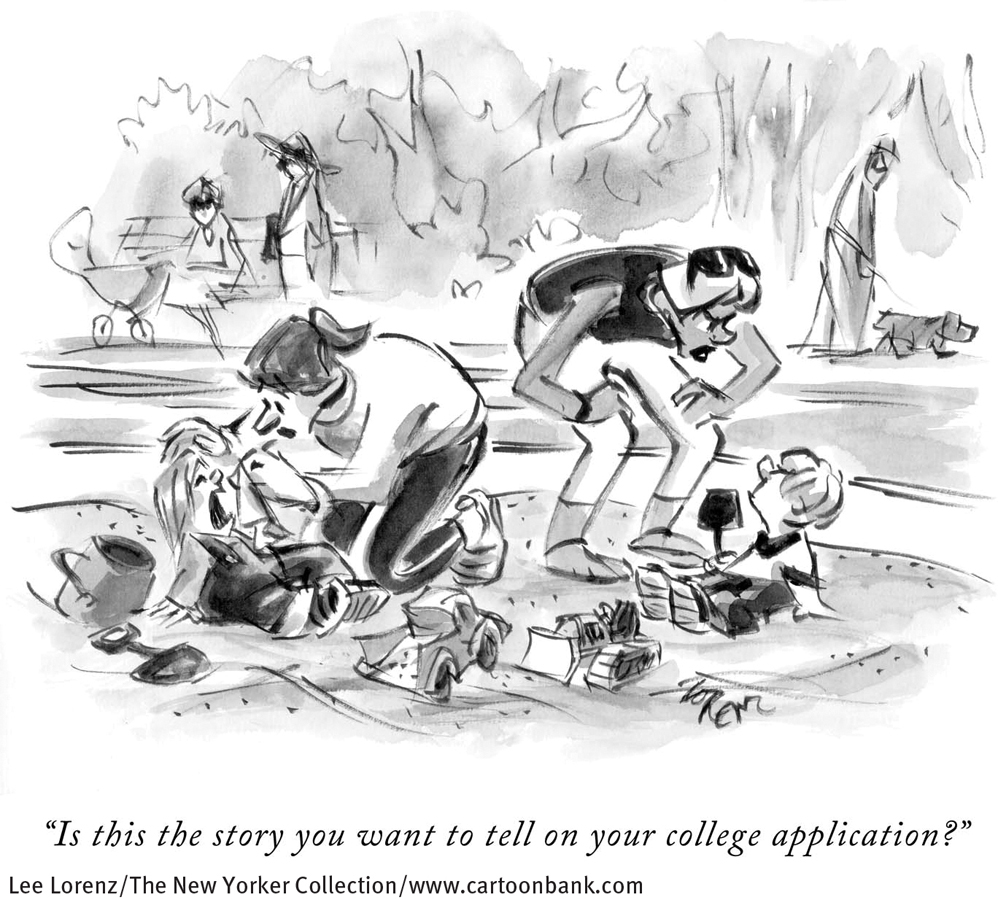

Extensive investigations indicate that ADHD is overdiagnosed in the United States, so many children who are receiving stimulants may, in fact, have been inaccurately diagnosed (Batstra et al., 2014; Rapport et al., 2008). In addition, a number of clinicians and parents have questioned the safety of stimulants. During the late 1980s, several lawsuits were filed against physicians, schools, and even the American Psychiatric Association, claiming misuse of Ritalin (Safer, 1994). Most of the suits were dismissed, but the media blitz that surrounded them affected public perceptions. Ritalin has also become a popular recreational drug among teenagers and young adults; some snort it to get high, others use it to stay alert or improve their performance at school or work. A number of young people become dependent on it, further raising public concerns about the drug.

On the positive side, stimulant drugs are apparently very helpful to children and adults who do suffer from ADHD (Sibley et al., 2014; Carlson et al., 2010). As you will see, behavioral programs are also effective in many cases but not in all, and tend to be most effective when they are used in concert with stimulant drugs. When children with ADHD are taken off the drugs, many fare badly.

Why has there been a sizable increase in the diagnosis and treatment of ADHD over the past few decades?

Most studies to date have indicated that stimulants are safe for the majority of people with ADHD (Berg et al., 2014; Rapport et al., 2008). Their undesired effects are usually no worse than insomnia, stomachaches, headaches, or loss of appetite. However, some research and case reports suggest that, in a small number of cases, stimulants may increase the risk of developing mild tremors or tics (Waugh, 2013), developing psychotic symptoms (Schwarz & Cohen, 2013), or having a heart attack—

BEHAVIOR THERAPY AND COMBINATION THERAPIESBehavioral therapy has been used to help treat many people with ADHD. Parents and teachers learn how to reward children for their attentiveness or self-

Multicultural Factors and ADHDThroughout this book, you have seen that race often affects how people are diagnosed and treated for various psychological disorders. Thus, you should not be totally surprised that race also seems to come into play with regard to ADHD.

A number of studies indicate that African American and Hispanic American children with significant attention and activity problems are less likely than white American children with similar symptoms to be assessed for ADHD, receive a diagnosis of ADHD, or undergo treatment for it (Morgan et al., 2014; Bussing et al., 2005, 2003, 1998). Moreover, among those who do receive such a diagnosis and treatment, children from racial minorities are less likely than white American children to be treated with stimulant drugs or a combination of stimulants and behavioral therapy—

In part, these racial differences in diagnosis and treatment are tied to economic factors. Studies consistently show that poorer children are less likely than wealthier ones to be identified as having ADHD and are less likely to receive effective treatment, and racial minority families have, on average, lower incomes and weaker insurance coverage than white American families. Consistent with this point, one study found that privately insured African American children with ADHD receive higher, more effective doses of stimulant drugs than do Medicaid-

BETWEEN THE LINES

In Their Words

“I want to thank my mom and my dad up in heaven for disobeying the doctor’s orders and not medicating their hyperactive girl and finding out what she was into instead.”

Audra McDonald, Tony Award–

Some clinical theorists further believe that social bias and stereotyping may contribute to these racial differences in diagnosis and treatment. They argue that our society often views the symptoms of ADHD as medical problems when exhibited by white American children but as indicators of poor parenting, lower IQ, substance use, or violence when displayed by African American and Hispanic American children (Duval-

Whatever the reason—

Autism Spectrum Disorder

Autism spectrum disorder, a pattern first identified by psychiatrist Leo Kanner in 1943, is marked by extreme unresponsiveness to other people, severe communication deficits, and highly rigid and repetitive behaviors, interests, and activities (APA, 2013) (see Table 17-6). These symptoms appear early in life, typically before 3 years of age. Just a decade ago, the disorder seemed to affect around 1 out of every 2,000 children. However, in recent years there has been a steady increase in the number of children diagnosed with autism spectrum disorder, and it now appears that as many as 1 in 68 children display this pattern (CDC, 2014). Jennie is one such child:

autism spectrum disorder A developmental disorder marked by extreme unresponsiveness to others, severe communication deficits, and highly repetitive and rigid behaviors, interests, and activities.

autism spectrum disorder A developmental disorder marked by extreme unresponsiveness to others, severe communication deficits, and highly repetitive and rigid behaviors, interests, and activities.

Ms. D’Angelo [a special education teacher] first observed Jennie [Hobson] in a small classroom over a 5-

Ms. D’Angelo noticed that Jennie did not speak and vocalized only when making her soft sounds. The volume of her sounds rarely changed but she appeared to make the sounds when bored or anxious. Jennie made no effort to communicate with others and was often oblivious to others. She was sometimes startled when asked to do something. Despite her lack of expressiveness, Jennie did understand and adhere to simple requests from others. She complied readily when told to get her lunch, use the bathroom, or retrieve an item in the classroom….

Jennie had a “picture book” with photographs of items she might want or need. Jennie never picked up the book or presented it to anyone but did follow directions to use the book to make requests. When shown the book and asked to point, Jennie either pushed the book onto the desk if she did not want anything or pointed to one of five photographs (i.e., a lunch box, cookie, glass of water, favorite toy, or toilet) if she did want something….

Following her classroom observations of Jennie, Ms. D’Angelo had an extensive conversation with Mr. and Mrs. Hobson. They said Jennie “had always been like this” and gave examples of her early impairment. Both said Jennie was “different” as a baby when she resisted being held and when she failed to talk by age 3 years…. Mr. and Mrs. Hobson had enrolled their daughter in her current school when she was 4 years old.

(Kearney, 2013, pp. 125-

|

Autism Spectrum Disorder |

|

|---|---|

|

1. |

Individual displays continual deficiencies in various areas of communication and social interaction, including the following: • Social- |

|

2. |

Individual displays significant restriction and repetition in behaviors, interests, or activities, including two or more of the following: • Exaggerated and repeated speech patterns, movements, or object use • Inflexible demand for same routines, statements, and behaviors • Highly restricted, fixated, and overly intense interests • Over- |

|

3. |

Individual develops symptoms by early childhood. |

|

4. |

Individual experiences significant impairment. |

|

(Information from: APA, 2013.) |

|

Around 80 percent of all cases of autism spectrum disorder occur in boys. As many as 90 percent of children with the disorder remain significantly disabled into adulthood. They have enormous difficulty maintaining employment, performing household tasks, and leading independent lives (Sicile-

The individual’s lack of responsiveness and social reciprocity—extreme aloofness, lack of interest in other people, low empathy, and inability to share attention with others—

Communication problems take various forms in autism spectrum disorder. The nonverbal behaviors of these individuals are often at odds with their efforts at verbal communication. They may not, for example, use a proper tone when talking. It is also common for autistic persons to show few or no facial expressions or body gestures. In addition, a number are unable to maintain proper eye contact during interactions. Recall, for example, that Jennie “rarely made eye contact with anyone.”

Many autistic people have great difficulty understanding speech or using language for conversational purposes. In fact, like Jennie, approximately half fail to speak or develop language skills (Paul & Gilbert, 2011). Those who do talk may have rigid and repetitious speech patterns. One of the most common speech peculiarities is echolalia, the exact echoing of phrases spoken by others. The individuals repeat the words with the same accent or inflection, but with no sign of understanding or intent of communicating. Some even repeat a sentence days after they have heard it (delayed echolalia). Another speech oddity is pronominal reversal, or confusion of pronouns—

Autistic people also display a wide range of highly rigid and repetitive behaviors, interests, and activities that extend beyond speech patterns. Typically they become very upset at minor changes in objects, persons, or routines and resist any efforts to change their own repetitive behaviors. Jennie’s special education teacher noticed that she was most aggressive when introduced to something or someone new.

PsychWatch

What Happened to Asperger’s Disorder?

Around the time that Leo Kanner first identified autism in the early 1940s, a Viennese physician named Hans Asperger observed a similar syndrome that came to be known—

For decades, clinicians believed that Asperger’s disorder was closely related to autism. The disorder was included in past editions of the DSM and was widely diagnosed. But then, with the publication of DSM-

Similarly, some children with the disorder react with tantrums if a parent wears an unfamiliar pair of glasses, a chair is moved to a different part of the room, or a word in a song is changed. Kanner (1943) labeled such reactions a perseveration of sameness. Many also become strongly attached to particular objects—

People with autism may display motor movements that are unusual, rigid, and repetitive. They may jump, flap their arms, twist their hands and fingers, rock, walk on their toes, spin, and make faces. These acts are called self-

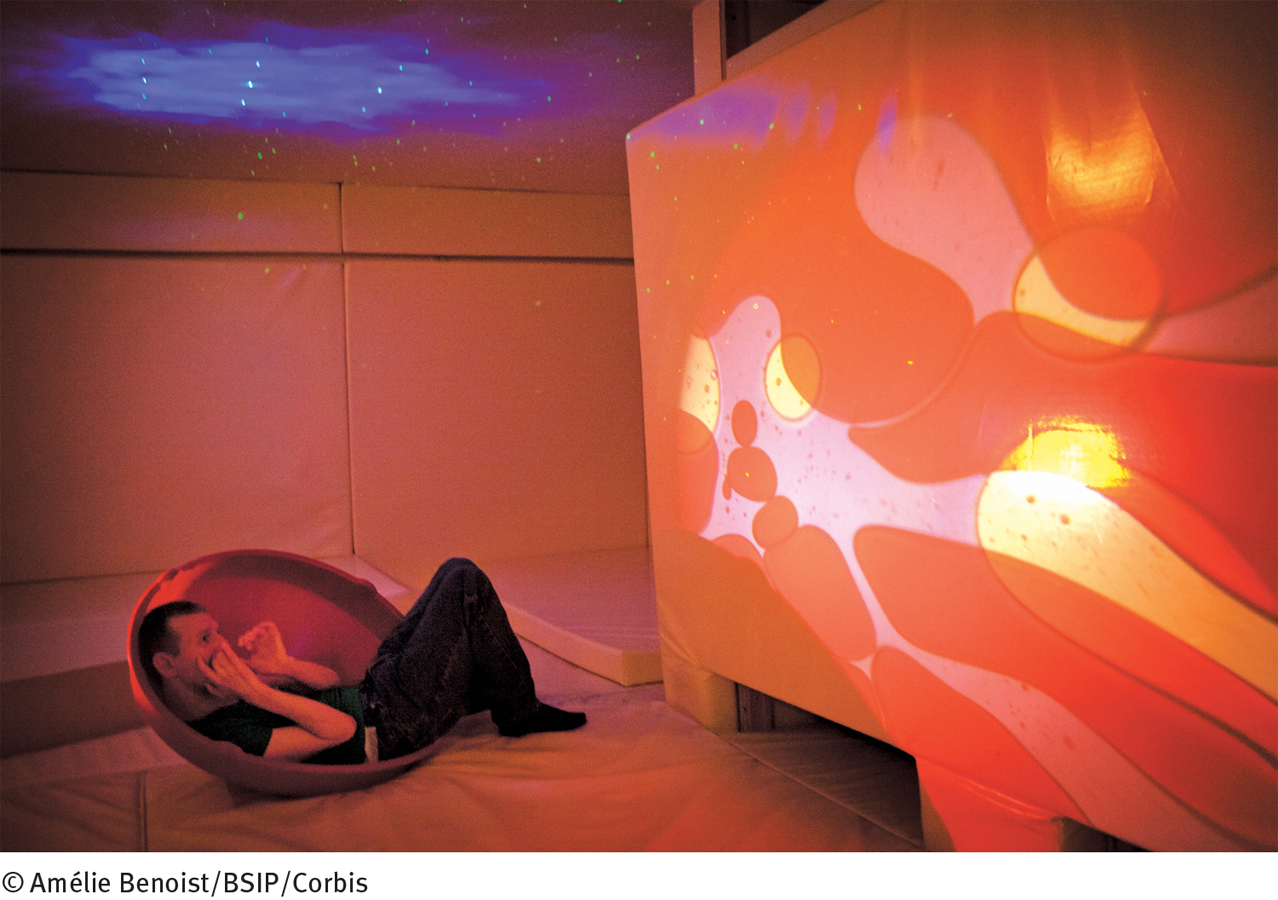

The symptoms of autism spectrum disorder suggest a very disturbed and contradictory pattern of reactions to stimuli (see PsychWatch below). Sometimes the individuals seem overstimulated by sights and sounds and appear to be trying to block them out (called hyperreactivity), while at other times they seem understimulated and appear to be performing self-

What Are the Causes of Autism Spectrum Disorder?A variety of explanations have been offered for autism spectrum disorder. This is one disorder for which sociocultural explanations have probably been overemphasized. In fact, such explanations initially led investigators in the wrong direction. More recent work in the psychological and biological spheres has persuaded clinical theorists that cognitive limitations and brain abnormalities are the primary causes of this disorder.

SOCIOCULTURAL CAUSESAt first, theorists thought that family dysfunction and social stress were the primary causes of autism spectrum disorder. When he first identified this disorder, for example, Kanner argued that particular personality characteristics of the parents created an unfavorable climate for development and contributed to the disorder (Kanner, 1954, 1943). He saw these parents as very intelligent yet cold—

Similarly, some clinical theorists have proposed that a high degree of social and environmental stress is a factor in the disorder. Once again, however, research has not supported this notion. Investigators who have compared autistic children with nonautistic children have found no differences in the rate of parental death, divorce, separation, financial problems, or environmental stimulation (Landrigan, 2011; Cox et al., 1975).

PSYCHOLOGICAL CAUSESAccording to certain theorists, people with autism spectrum disorder have a central perceptual or cognitive disturbance that makes normal communication and interactions impossible. One influential explanation holds that those with the disorder fail to develop a theory of mind—an awareness that other people base their behaviors on their own beliefs, intentions, and other mental states, not on information that they have no way of knowing (Kimhi et al., 2014; O’Nions et al., 2014; Frith, 2000).

theory of mind An awareness that other people base their behaviors on their own beliefs, intentions, and other mental states, not on information that they have no way of knowing.

theory of mind An awareness that other people base their behaviors on their own beliefs, intentions, and other mental states, not on information that they have no way of knowing.

By 3 to 5 years of age, most normal children can take the perspective of another person into account and use it to anticipate what the person will do. In a way, they learn to read others’ minds. Let us say, for example, that we watch Jessica place a marble in a container and then we observe Frank move the marble to a nearby room while Jessica is taking a nap. We know that later Jessica will search first in the container for the marble because she is not aware that Frank moved it. We know that because we take Jessica’s perspective into account. A normal child would also anticipate Jessica’s search correctly. An autistic child would not. He or she would expect Jessica to look in the nearby room because that is where the marble actually is. Jessica’s own mental processes would be unimportant to the person.

Studies show that people with autism spectrum disorder do indeed have this kind of “mind-

BIOLOGICAL CAUSESFor years researchers have tried to determine what biological abnormalities might cause theory-

PsychWatch

A Special Kind of Talent

Most people are familiar with the savant syndrome, thanks to Dustin Hoffman’s portrayal of a man with autism in the movie Rain Man. The savant skills that Hoffman portrayed—

A savant (French for “learned” or “clever”) is a person with a major mental disorder or intellectual handicap who has some spectacular ability. Often these abilities are remarkable only in light of the handicap, but sometimes they are remarkable by any standard (Treffert, 2014; Yewchuk, 1999). A common savant skill is calendar calculating, the ability to calculate what day of the week a date will fall on, such as New Year’s Day in 2050. A common musical skill such people may possess is the ability to play a piece of classical music flawlessly from memory after hearing it only once. Other individuals can paint exact replicas of scenes they saw years ago.

Some theorists believe that savant skills do indeed represent special forms of cognitive functioning; others propose that the skills are merely a positive side to certain cognitive deficits (Treffert, 2014; Howlin, 2012; Scheuffgen et al., 2000). Special memorization skills, for example, may be facilitated by the very narrow and intense focus that people with autism often have.

Some studies have also linked autism spectrum disorder to prenatal difficulties or birth complications (Reichenberg et al., 2011). For example, the chances of developing the disorder are higher when the mother had rubella (German measles) during pregnancy, was exposed to toxic chemicals before or during pregnancy, or had complications during labor or delivery.

Finally, researchers have identified specific biological abnormalities that may contribute to autism spectrum disorder. One line of research has pointed to the cerebellum (Allen, 2011; Teicher et al., 2008; Pierce & Courchesne, 2002, 2001). Brain scans and autopsies show abnormal development in this brain area occurring early in the life of autistic people. Scientists have long known that the cerebellum coordinates movement in the body, but they now suspect that it also helps control a person’s ability to shift attention rapidly. It may be that people whose cerebellum develops abnormally will have great difficulty adjusting their level of attention, following verbal and facial cues, and making sense of social information—

cerebellum An area of the brain that coordinates movement in the body and perhaps helps control a person’s ability to shift attention rapidly.

cerebellum An area of the brain that coordinates movement in the body and perhaps helps control a person’s ability to shift attention rapidly.

In a similar vein, neuroimaging studies indicate that many autistic children have increased brain volume and white matter and structural abnormalities in the brain’s limbic system, brain stem nuclei, and amygdala (Bachevalier, 2011; Bauman, 2011). Many people with autism also have reduced activity in the brain’s temporal and frontal lobes when they perform language and motor tasks (Taylor et al., 2014; Escalante et al., 2003).

Given such findings, many researchers believe that autism spectrum disorder may have multiple biological causes (Hollander, 2013; Hollander et al., 2011). Perhaps each of the relevant biological factors (genetic, prenatal, birth, and postnatal) can eventually lead to a common problem in the brain—

Finally, because it has received so much attention over the past 15 years, it is worth examining a biological explanation for autism spectrum disorder that has not been borne out—

Why do many people still believe that the MMR vaccine causes autism spectrum disorder, despite so much evidence to the contrary?

However, virtually all research conducted since 1998 has argued against this theory (Taylor, Swerdfeger, & Eslick, 2014; Ahearn, 2010; Uchiyama et al., 2007). First, epidemiological studies repeatedly have found that children throughout the world who receive the MMR vaccine have the same prevalence of autism as those who do not receive the vaccine. Second, according to research, children with autism do not have more measles viruses in their bodies than children without autism. Third, autistic children do not have the special stomach disease proposed by this theory. Finally, careful reexaminations of the original study have indicated that it was methodologically flawed and perhaps manipulated and that it failed to demonstrate any relationship between the MMR vaccine and the development of autism spectrum disorder (Lancet, 2010). Unfortunately, despite this clear refutation, many concerned parents now choose to withhold the MMR vaccine from their young children, leaving them highly vulnerable to diseases that can be very dangerous.

How Do Clinicians and Educators Treat Autism Spectrum Disorder?Treatment can help people with autism spectrum disorder adapt better to their environment, although no treatment yet known totally reverses the autistic pattern. Treatments of particular help are cognitive-

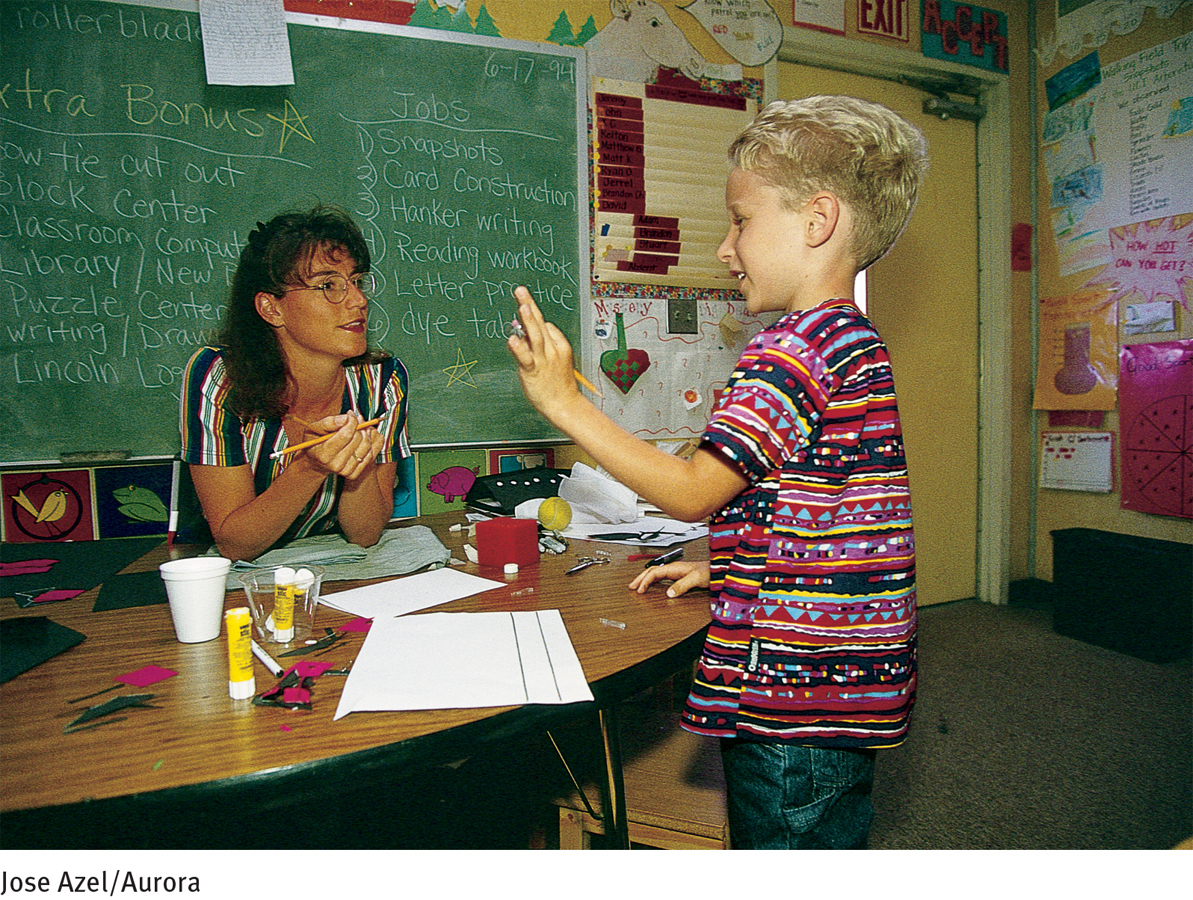

COGNITIVE-

A pioneering, long-

One behavioral program that has achieved considerable success is the Learning Experiences: An Alternative Program (LEAP) for preschoolers with autism (Boyd et al., 2014; Kohler et al., 2005). In this program, 4 autistic children are integrated with 10 nonautistic children in a classroom. The nonautistic children learn how to use modeling and operant conditioning in order to help teach social, communication, play, and other skills to the autistic children. The program has been found to improve significantly the cognitive functioning of autistic children, as well as their social and peer interactions, play behaviors, and other behaviors. Moreover, the nonautistic children in the classroom experience no negative effects as a result of serving as intervention agents.

As such programs suggest, therapies for people with autism spectrum disorder, particularly behavioral therapies, tend to provide the most benefit when they are started early in the children’s lives (Carter et al., 2011; Magiati et al., 2011). Very young autistic children often begin with services at home, but ideally, by the age of 3 they attend special programs outside the home. A federal law lists autism spectrum disorder as 1 of 10 disorders for which school districts must provide a free education from birth to age 22, in the least restrictive or most appropriate setting possible. Typically, services are provided by education, health, or social service agencies until the children reach 3 years of age; then the department of education for each state determines which services will be offered.

Given the recent increases in the prevalence of autism spectrum disorder, many school districts are now trying to provide education and training for autistic children in special classes that operate at the district’s own facilities (Wilczynski et al., 2011). However, most school districts remain ill-

COMMUNICATION TRAININGEven when given intensive behavioral treatment, half of the people with autism spectrum disorder remain speechless. To help address this, they are often taught other forms of communication, including sign language and simultaneous communication, a method combining sign language and speech. They may also learn to use augmentative communication systems, such as “communication boards” or computers that use pictures, symbols, or written words to represent objects or needs (Prelock et al., 2011; Ramdoss et al., 2011). A child may point to a picture of a fork to give the message “I am hungry,” for instance, or point to a radio for “I want music.” Recall, for example, the use of a “picture book” by Jennie, the child whose case introduced this section.

augmentative communication system A method for enhancing the communication skills of people with autism spectrum disorder, intellectual disability, or cerebral palsy by teaching them to point to pictures, symbols, letters, or words on a communication board or computer.

augmentative communication system A method for enhancing the communication skills of people with autism spectrum disorder, intellectual disability, or cerebral palsy by teaching them to point to pictures, symbols, letters, or words on a communication board or computer.

Some programs now use child-

PARENT TRAININGToday’s treatment programs for autism spectrum disorder involve parents in a variety of ways. Behavioral programs, for example, often train parents so that they can use behavioral techniques at home (Sicile-

In addition to parent-

COMMUNITY INTEGRATIONMany of today’s school-

Intellectual Disability

Ed Murphy, aged 26, can tell us what it’s like to be considered “mentally retarded”:

What is retardation? It’s hard to say. I guess it’s having problems thinking. Some people think that you can tell if a person is retarded by looking at them. If you think that way you don’t give people the benefit of the doubt. You judge a person by how they look or how they talk or what the tests show, but you can never really tell what is inside the person.

(Bogdan & Taylor, 1976, p. 51)

For much of his life Ed was labeled mentally retarded and was educated and cared for in special institutions. During his adult years, clinicians discovered that Ed’s intellectual ability was in fact higher than had been assumed. In the meantime, however, he had lived the childhood and adolescence of a person labeled mentally retarded, and his statement reveals the kinds of difficulties often faced by people with this disorder.

In DSM-

People receive a diagnosis of intellectual disability (ID) when they display general intellectual functioning that is well below average, in combination with poor adaptive behavior (APA, 2013). That is, in addition to having a low IQ (a score of 70 or below), a person with ID has great difficulty in areas such as communication, home living, self-

intellectual disability (ID) A disorder marked by intellectual functioning and adaptive behavior that are well below average. Previously called mental retardation.

intellectual disability (ID) A disorder marked by intellectual functioning and adaptive behavior that are well below average. Previously called mental retardation.

|

Intellectual Disability |

|

|---|---|

|

1. |

Individual displays deficient intellectual functioning in areas such as reasoning, problem- |

|

2. |

Individual displays deficient adaptive functioning in at least one area of daily life, such as communication, social involvement, or personal independence, across home, school, work, or community settings. The limitations extend beyond those displayed by most other persons of his or her age and necessitate ongoing support at school, work, or independent living. |

|

3. |

The deficits begin during the developmental period (before the age of 18). |

|

(Information from: APA, 2013) |

|

Assessing IntelligenceEducators and clinicians administer intelligence tests to measure intellectual functioning (see Chapter 4). These tests consist of a variety of questions and tasks that rely on different aspects of intelligence, such as knowledge, reasoning, and judgment. Having difficulty in just one or two of these subtests or areas of functioning does not necessarily reflect low intelligence (see PsychWatch below). It is an individual’s overall test score, or intelligence quotient (IQ), that is thought to indicate general intellectual ability.

intelligence quotient (IQ) A score derived from intelligence tests that theoretically represents a person’s overall intellectual capacity.

intelligence quotient (IQ) A score derived from intelligence tests that theoretically represents a person’s overall intellectual capacity.

Many theorists have questioned whether IQ tests are indeed valid. Do they actually measure what they are supposed to measure? The correlation between IQ and school performance is rather high—

Are there other kinds of intelligence that IQ tests might fail to assess? What might that suggest about the validity and usefulness of these tests?

Intelligence tests also appear to be socioculturally biased, as you read in Chapter 4. Children reared in households at the middle and upper socioeconomic levels tend to have an advantage on the tests because they are regularly exposed to the kinds of language and thinking that the tests evaluate. The tests rarely measure the “street sense” needed for survival by people who live in poor, crime-

If IQ tests do not always measure intelligence accurately and objectively, then the diagnosis of intellectual disability also may be biased. That is, some people may receive the diagnosis partly because of test inadequacies, cultural differences, discomfort with the testing situation, or the bias of a tester.

Assessing Adaptive FunctioningDiagnosticians cannot rely solely on a cutoff IQ score of 70 to determine whether a person suffers from intellectual disability. Some people with a low IQ are quite capable of managing their lives and functioning independently, while others are not. The cases of Brian and Jeffrey show the range of adaptive abilities.

Brian comes from a lower-

Jeffrey comes from an upper-

BETWEEN THE LINES

In Their Words

“The IQ test was invented to predict academic performance, nothing else. If we wanted something that would predict life success, we’d have to invent another test completely.”

Robert Zajonc, psychologist, 1984

Brian seems well adapted to his environment outside school. However, Jeffrey’s limitations are pervasive. In addition to his low IQ score, Jeffrey has difficulty meeting challenges at home and elsewhere. Thus a diagnosis of intellectual disability may be more appropriate for Jeffrey than for Brian.

Several scales have been developed to assess adaptive behavior. Here again, however, some people function better in their lives than the scales predict, while others fall short. Thus to properly diagnose intellectual disability, clinicians should probably observe the adaptive functioning of each individual in his or her everyday environment, taking both the person’s background and the community’s standards into account. Even then, such judgments may be subjective, as clinicians may not be familiar with the standards of a particular culture or community.

PsychWatch

Reading and ‘Riting and ‘Rithmetic

Between 15 and 20 percent of children, boys more often than girls, develop slowly and function poorly compared with their peers in a single area such as learning, communication, or motor coordination (APA, 2013; Goldstein et al., 2011). The children do not suffer from intellectual disability, and in fact they are often very bright, yet their problems may interfere with school performance, daily living, and in some cases social interactions. Similar difficulties may be seen in the children’s close biological relatives (APA, 2013; Watson et al., 2008). According to DSM-

Children with a specific learning disorder have significant difficulties in acquiring reading, writing, arithmetic, or mathematical reasoning skills. Across the United States, children with such problems comprise the largest subgroup of those placed in special education classes (Watson et al., 2008). Some of these children read slowly or inaccurately or have difficulty understanding the meaning of what they are reading, difficulties also known as dyslexia (Boets, 2014). Others spell or write very poorly. And still others have great trouble remembering number facts, performing calculations, or reasoning mathematically.

The communication disorders include language disorder, speech sound disorder, and childhood-

Finally, children with developmental coordination disorder perform coordinated motor activities at a level well below that of others their age (APA, 2013). Younger children with this disorder are clumsy and slow to master skills such as tying shoelaces, buttoning shirts, and zipping pants. Older children with the disorder may have great difficulty assembling puzzles, building models, playing ball, and printing or writing.

Studies have linked these various disorders to genetic defects, brain abnormalities, birth injuries, lead poisoning, inappropriate diet, sensory or perceptual dysfunction, and poor teaching (Richlan, 2014; APA, 2013; Yeates et al., 2010; Golden, 2008). Research implicating each of these factors has been limited, however, and the precise causes of the disorders remain unclear.

Some of the disorders respond to special treatment approaches (McArthur et al., 2013; Feifer, 2010; Miller, 2010). Reading therapy, for example, is very helpful in mild cases of dyslexia, and speech therapy brings about complete recovery in many cases of speech disorder. Furthermore, the various disorders often disappear before adulthood, even without any treatment.

What Are the Features of Intellectual Disability?The most consistent feature of intellectual disability is that the person learns very slowly (Sturmey & Didden, 2014; AAIDD, 2013). Other areas of difficulty are attention, short-

Mild IDSome 80 to 85 percent of all people with intellectual disability fall into the category of mild ID (IQ 50–

mild ID A level of intellectual disability (IQ between 50 and 70) at which people can benefit from education and can support themselves as adults.

mild ID A level of intellectual disability (IQ between 50 and 70) at which people can benefit from education and can support themselves as adults.

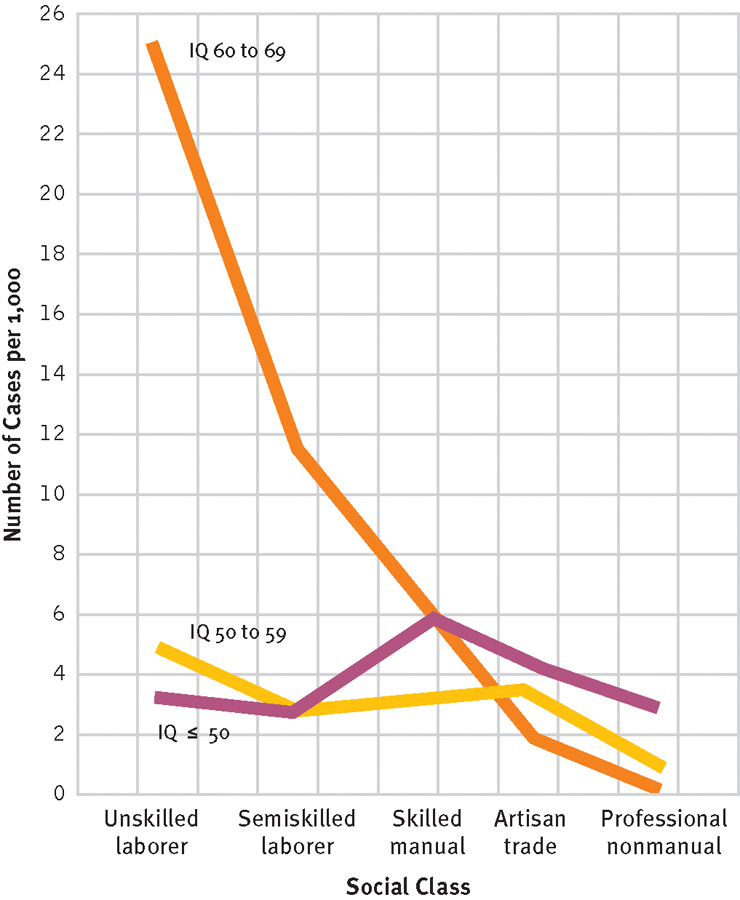

Research has linked mild ID mainly to sociocultural and psychological causes, particularly poor and unstimulating environments during a child’s early years, inadequate parent-

Intellectual disability and socioeconomic class

The prevalence of mild ID is much higher in the lower socioeconomic classes than in the upper classes. In contrast, other levels of intellectual disability are evenly distributed among the various classes.

Although sociocultural and psychological factors seem to be the leading causes of mild ID, at least some biological factors also may be operating. Studies suggest, for example, that a mother’s moderate drinking, drug use, or malnutrition during pregnancy may lower her child’s intellectual potential (Hart & Ksir, 2013). Malnourishment during a child’s early years also may hurt his or her intellectual development, although this effect can usually be reversed at least partly if a child’s diet is improved before too much time goes by.

Moderate, Severe, and Profound IDApproximately 10 percent of those with intellectual disability function at a level of moderate ID (IQ 35–

moderate ID A level of intellectual disability (IQ between 35 and 49) at which people can learn to care for themselves and can benefit from vocational training.

moderate ID A level of intellectual disability (IQ between 35 and 49) at which people can learn to care for themselves and can benefit from vocational training.

Approximately 3 to 4 percent of people with intellectual disability display severe ID (IQ 20-

severe ID A level of intellectual disability (IQ between 20 and 34) at which people require careful supervision and can learn to perform basic work in structured and sheltered settings.

severe ID A level of intellectual disability (IQ between 20 and 34) at which people require careful supervision and can learn to perform basic work in structured and sheltered settings.

Around 1 to 2 percent of all people with intellectual disability function at a level of profound ID (IQ below 20). This level is very noticeable at birth or early infancy. With training, people with profound ID may learn or improve basic skills such as walking, some talking, and feeding themselves. They need a very structured environment, with close supervision and considerable help, including a one-

profound ID A level of intellectual disability (IQ below 20) at which people need a very structured environment with close supervision.

profound ID A level of intellectual disability (IQ below 20) at which people need a very structured environment with close supervision.

Severe and profound levels of intellectual disability often appear as part of larger syndromes that include severe physical handicaps. The physical problems are often even more limiting than the individual’s low intellectual functioning and in some cases can be fatal.

What Are the Biological Causes of Intellectual Disability?As you read earlier, the primary causes of mild ID are environmental, although biological factors may also be operating in many cases. In contrast, the main causes of moderate, severe, and profound ID are biological, although people who function at these levels also are strongly affected by their family and social environment (Sturmey & Didden, 2014; Fletcher, 2011). The leading biological causes of intellectual disability are chromosomal abnormalities, metabolic disorders, prenatal problems, birth complications, and childhood diseases and injuries.

CHROMOSOMAL CAUSESThe most common of the chromosomal disorders that lead to intellectual disability is Down syndrome, named after Langdon Down, the British physician who first identified it. Down syndrome occurs in fewer than 1 of every 1,000 live births, but the rate increases significantly when the mother’s age is over 35. Many older expectant mothers are now encouraged to undergo amniocentesis (testing of the amniotic fluid that surrounds the fetus) or other tests during the early months of pregnancy to identify Down syndrome and other chromosomal abnormalities.

Down syndrome A form of intellectual disability caused by an abnormality in the 21st chromosome.

Down syndrome A form of intellectual disability caused by an abnormality in the 21st chromosome.

People with Down syndrome may have a small head, flat face, slanted eyes, high cheekbones, and, in some cases, protruding tongue. The latter may affect their ability to pronounce words clearly. They are often very affectionate with family members but in general display the same range of personality characteristics as people in the general population.

Several types of chromosomal abnormalities may cause Down syndrome (Hazlett et al., 2011). The most common type (94 percent of cases) is trisomy 21, in which the person has three free-

Fragile X syndrome is the second most common chromosomal cause of intellectual disability. Children born with a fragile X chromosome (that is, an X chromosome with a genetic abnormality that leaves it prone to breakage and loss) generally display mild to moderate degrees of intellectual dysfunctioning, language impairments, and in some cases, behavioral problems (Hagerman, 2011). Typically, they are shy and anxious.

BETWEEN THE LINES

About the Sex Chromosome

The 23rd chromosome, whose abnormality causes Fragile X syndrome, is the smallest human chromosome.

The 23rd chromosome determines a person’s sex and thus is also referred to as the sex chromosome.

In males, the 23rd chromosome pair consists of an X chromosome and a Y chromosome.

In females, the 23rd chromosome pair consists of two X chromosomes.

METABOLIC CAUSESIn metabolic disorders, the body’s breakdown or production of chemicals is disturbed. The metabolic disorders that affect intelligence and development are typically caused by the pairing of two defective recessive genes, one from each parent. Although one such gene would have no influence if it were paired with a normal gene, its pairing with another defective gene leads to major problems for the child.

The most common metabolic disorder to cause intellectual disability is phenylketonuria (PKU), which strikes 1 of every 14,000 children. Babies with PKU appear normal at birth but cannot break down the amino acid phenylalanine. The chemical builds up and is converted into substances that poison the system, causing severe intellectual dysfunction and several other symptoms (Waisbren, 2011). Today infants can be screened for PKU, and if started on a special diet before 3 months of age, they may develop normal intelligence.

Children with Tay-

PRENATAL AND BIRTH-

Other prenatal problems may also cause intellectual disability. As you saw in Chapter 12, children whose mothers drink too much alcohol during pregnancy may be born with fetal alcohol syndrome, a group of very serious problems that includes mild to severe ID (Bakoyiannis et al, 2014; Hart & Ksir, 2014). In fact, a generally safe level of alcohol consumption during pregnancy has not been established by research. In addition, certain maternal infections during pregnancy—

fetal alcohol syndrome A group of problems in a child, including lower intellectual functioning, low birth weight, and irregularities in the hands and face, that result from excessive alcohol intake by the mother during pregnancy.

fetal alcohol syndrome A group of problems in a child, including lower intellectual functioning, low birth weight, and irregularities in the hands and face, that result from excessive alcohol intake by the mother during pregnancy.

Birth complications also can lead to problems in intellectual functioning. A prolonged period without oxygen (anoxia) during or after delivery can cause brain damage and intellectual disability in a baby. In addition, although premature birth does not necessarily lead to long-

BETWEEN THE LINES

Residential Shift

|

91,592 |

Number of children and adolescents with intellectual disability who lived in large state institutions in 1964 |

|

1,641 |

Children and adolescents with intellectual disability currently living in large state institutions |

|

(Breedlove et al. 2005) |

|

CHILDHOOD PROBLEMSAfter birth, particularly up to age 6, certain injuries and accidents can affect intellectual functioning and in some cases lead to intellectual disability. Poisonings, serious head injuries caused by accident or abuse, excessive exposure to X-

Interventions for People with Intellectual DisabilityThe quality of life attained by people with intellectual disability depends largely on sociocultural factors: where they live and with whom, how they are educated, and the growth opportunities available at home and in the community. Thus intervention programs for these individuals try to provide comfortable and stimulating residences, a proper education, and social and economic opportunities. At the same time, the programs seek to improve the self-

WHAT IS THE PROPER RESIDENCE?Until recent decades, parents of children with intellectual disability would send them to live in public institutions—

state school A state-

state school A state-

During the 1960s and 1970s, the public became more aware of these sorry conditions and, as part of the broader deinstitutionalization movement (see Chapter 15), demanded that many people with intellectual disability be released from the state schools (Harris, 2010). In many cases, the releases were done without adequate preparation or supervision. Like people with schizophrenia who were suddenly deinstitutionalized, those with intellectual disability were virtually dumped into the community. Often they failed to adjust and had to be institutionalized once again.

Since that time, reforms have led to the creation of small institutions and other community residences (group homes, halfway houses, local branches of larger institutions, and independent residences) that teach self-

normalization The principle that institutions and community residences should provide people with intellectual disability types of living conditions and opportunities that are similar to those enjoyed by the rest of society.

normalization The principle that institutions and community residences should provide people with intellectual disability types of living conditions and opportunities that are similar to those enjoyed by the rest of society.

Today the vast majority of children with intellectual disability live at home rather than in an institution. During adulthood and as their parents age, however, some people with intellectual disability require levels of assistance and opportunities that their families are unable to provide. A community residence becomes an appropriate alternative for them. Most people with intellectual disability, including almost all with mild ID, now spend their adult lives either in the family home or in a community residence (Sturmey & Didden, 2014; Sturmey, 2008).

WHICH EDUCATIONAL PROGRAMS WORK BEST?Because early intervention seems to offer such great promise, educational programs for people with intellectual disability may begin during the earliest years. The appropriate education depends on the person’s level of functioning. Educators hotly debate whether special classes or mainstreaming is most effective once the children enter school (McKenzie, McConkey, & Adnams, 2014; Hardman, Drew, & Egan, 2002).

What might be the benefits of mainstreaming compared with special education classes, and vice versa?

In special education, children with intellectual disability are grouped together in a separate, specially designed educational program. In contrast, in mainstreaming, or inclusion, they are placed in regular classes with students from the general school population. Neither approach seems consistently superior (McKenzie et al., 2014; Bebko & Weiss, 2006). It may well be that mainstreaming is better for some areas of learning and for some children, and special classes are better for others.

special education An approach to educating children with intellectual disability in which they are grouped together and given a separate, specially designed education.

special education An approach to educating children with intellectual disability in which they are grouped together and given a separate, specially designed education.

mainstreaming The placement of children with intellectual disability in regular school classes. Also known as inclusion.

mainstreaming The placement of children with intellectual disability in regular school classes. Also known as inclusion.

Teacher preparedness is another factor that may play into decisions about mainstreaming and special education classes. Many teachers report feeling inadequately prepared to provide training and support for children with intellectual disability, especially children who have additional problems (Scheuermann et al., 2003). Brief training courses for teachers appear to address such concerns (Campbell et al., 2003).

Teachers who work with students with intellectual disability often use operant conditioning principles to improve their students’ self-

WHEN IS THERAPY NEEDED?Like anyone else, people with intellectual disability sometimes have emotional and behavioral problems. Around 30 percent or more have a psychological disorder other than intellectual disability (Sturmey & Didden, 2014; Bouras & Holt, 2010). Furthermore, some suffer from low self-

HOW CAN OPPORTUNITIES FOR PERSONAL, SOCIAL, AND OCCUPATIONAL GROWTH BE INCREASED?People need to feel effective and competent in order to move forward in life. Those with intellectual disability are most likely to feel effective and competent if their communities allow them to grow and to make many of their own choices. Denmark and Sweden, where the normalization movement began, have again been leaders in this area, developing youth clubs that encourage those with intellectual disability to take risks and function independently. The Special Olympics program has also encouraged those with intellectual disability to be active in setting goals, to participate in their environment, and to interact socially with others (Glidden et al., 2011; Marks et al., 2010).

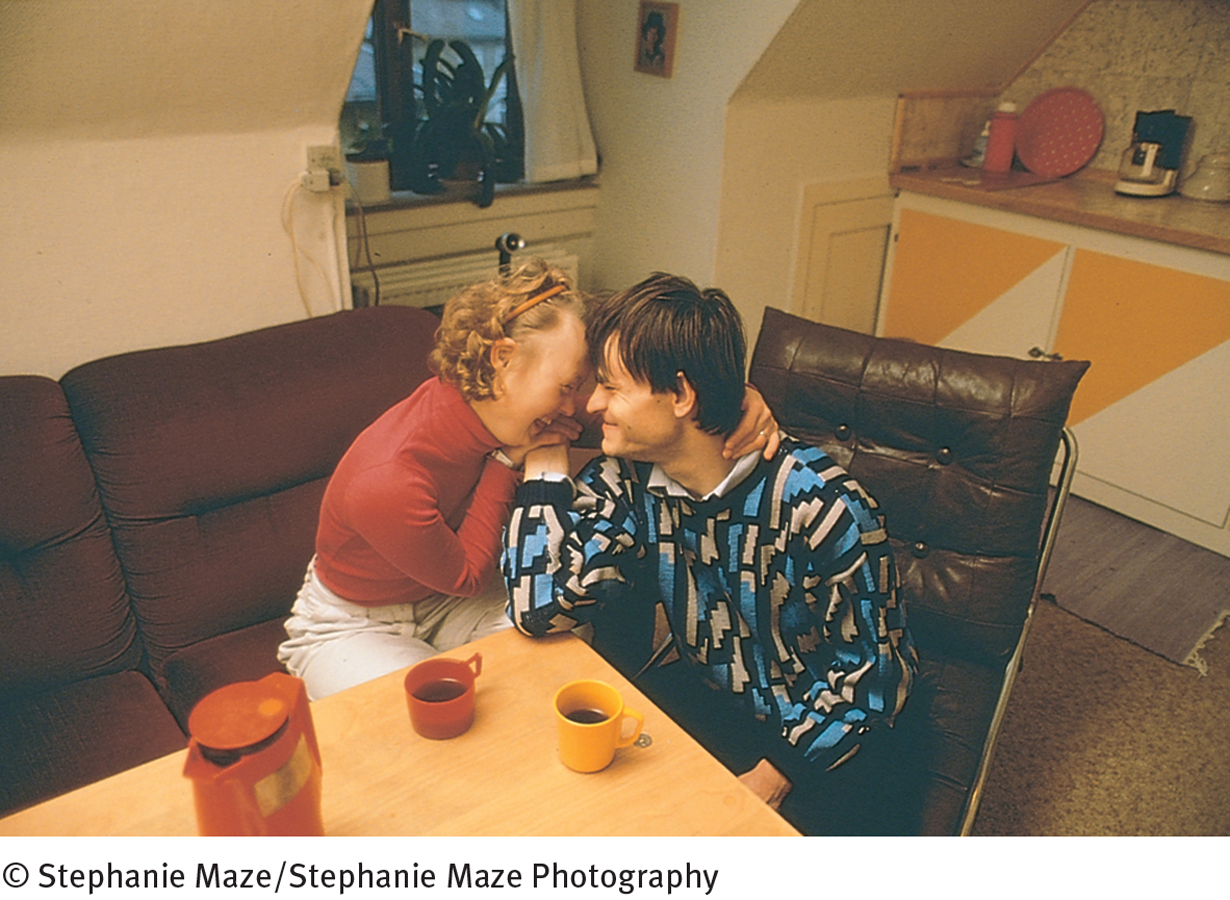

Socializing, sex, and marriage are difficult issues for people with intellectual disability and their families, but with proper training and practice, they usually can learn to use contraceptives and carry out responsible family planning (Lumley & Scotti, 2001). National advocacy organizations and a number of clinicians currently offer guidance in these matters, and some have developed dating skills programs (AAIDD, 2013; Segal, 2008).

Some states restrict marriage for people with intellectual disability. These laws are rarely enforced, though, and in fact many people with mild ID marry. Contrary to popular myths, the marriages can be very successful. And although some may be incapable of raising children, many are quite able to do so, either on their own or with special help and community services (Sturmey, 2014, 2008; AAIDD, 2013).

Finally, adults with intellectual disability—

sheltered workshop A protected and supervised workplace that offers job opportunities and training at a pace and level tailored to people with various psychological disabilities.

sheltered workshop A protected and supervised workplace that offers job opportunities and training at a pace and level tailored to people with various psychological disabilities.

Although training programs for people with intellectual disability have improved greatly in quality over the past 35 years, there are too few of them. Consequently, most participants do not receive a complete range of educational and occupational training services. Additional programs are required so that more people with intellectual disability may achieve their full potential, as workers and as human beings.