18.4 Substance Misuse in Later Life

Although alcohol use disorder and other substance use disorders are significant problems for many older persons, the prevalence of such patterns actually appears to decline after age 65, perhaps because of declining health or reduced income (Blazer & Wu, 2011; Berks & McCormick, 2008). The majority of older adults do not misuse alcohol or other substances, despite the fact that aging can sometimes be a time of considerable stress and in our society people often turn to alcohol and drugs during times of stress. Accurate data about the rate of substance abuse among older adults are difficult to gather because many elderly people do not suspect or admit that they have such a problem (Trevisan, 2014; Jeste et al., 2005).

Surveys find that 3 to 7 percent of older people, particularly men, have alcohol use disorder in a given year (Trevisan, 2014; Knight et al., 2006). Men under 30 are four times as likely as men over 60 to display a behavioral problem associated with excessive alcohol use, such as repeated falling, spells of dizziness or blacking out, secretive drinking, or social withdrawal. Older patients who are institutionalized, however, do display high rates of problem drinking. For example, alcohol problems among older people admitted to general and mental hospitals range from 15 percent to 49 percent, and estimates of alcohol-

BETWEEN THE LINES

Undesired Effects

It is estimated that 6 to 13 percent of emergency room visits by elderly people are tied to adverse medication reactions (Sleeper, 2010).

Researchers often distinguish between older problem drinkers who have had alcohol use disorder for many years, perhaps since their 20s, and those who do not start abusing alcohol until their 50s or 60s (in what is sometimes called “late-

InfoCentral

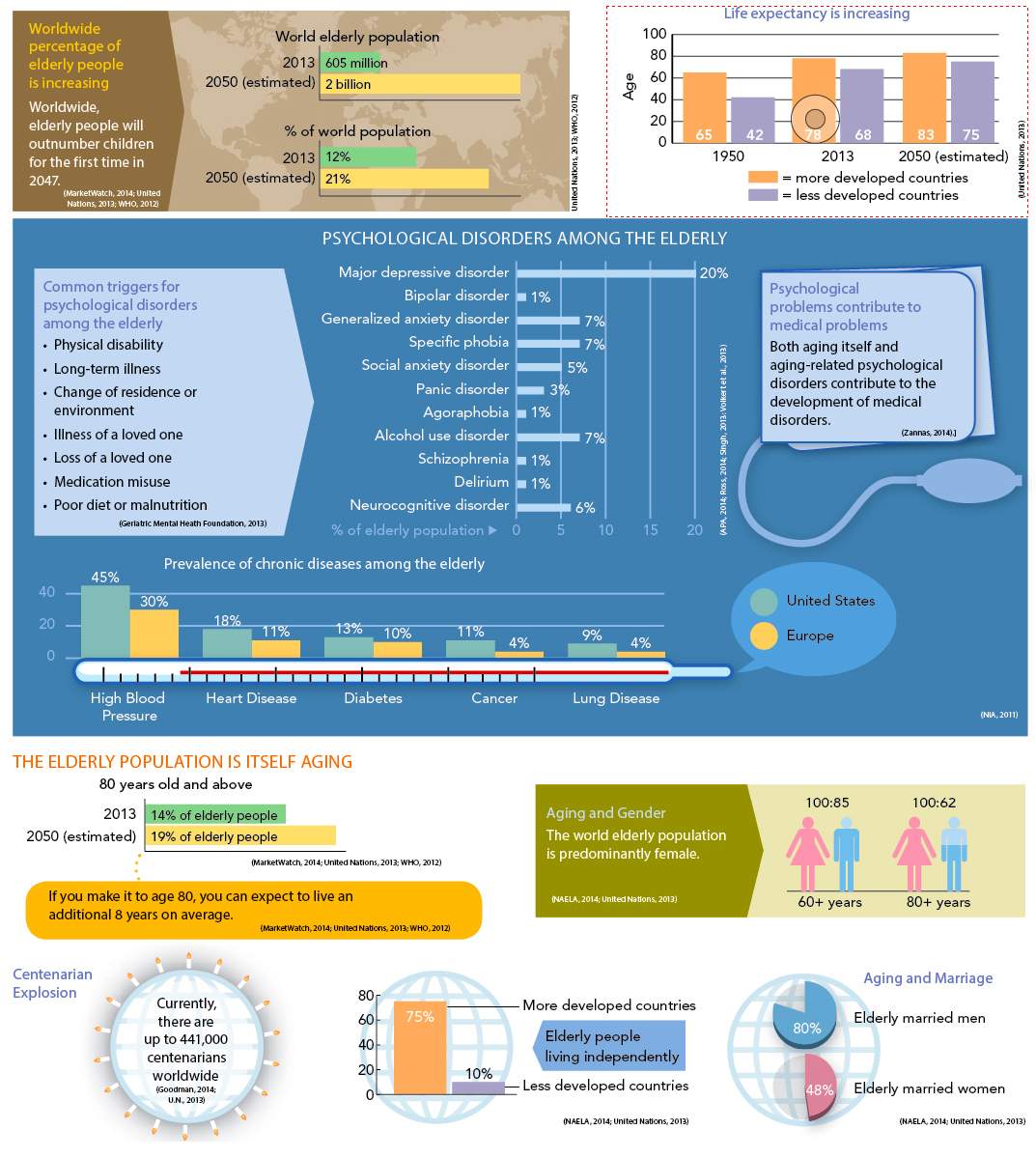

THE AGING POPULATION

The number and proportion of elderly people in the United States and around the world are ever-

BETWEEN THE LINES

Medications for the Elderly

|

70% |

Percentage of elderly persons who take cardiovascular drugs |

|

47% |

Percentage of elderly persons who take cholesterol- |

|

18% |

Percentage of elderly persons who take diabetes drugs |

|

14% |

Percentage of elderly persons who take antidepressant drugs |

|

(Information from: NCHS, 2014) |

|

A leading substance problem in the elderly is the misuse of prescription drugs (Cummings & Coffey, 2011; Volfson & Oslin, 2011). Most often the misuse is unintentional. In the United States, people over the age of 50 buy 77 percent of all prescription drugs and 61 percent of all over-

What changes in medical practice, patient education, or family interactions might address the problem of prescription drug misuse by the elderly?

Yet another drug-