Bringing Mental Health Services to the Workplace

Untreated psychological disorders are, collectively, among the 10 leading categories of work-related disorders and injuries (Negrini et al., 2014; Brough & Biggs, 2010; Kemp, 1994). Almost one-third of all employees are estimated to experience psychological problems that are serious enough to affect their work (Larsen et al., 2010). Psychological problems contribute to 60 percent of all absenteeism from work, up to 90 percent of industrial accidents, and to 65 percent of work terminations. Alcohol abuse and other substance use disorders are particularly damaging. The business world has often turned to clinical professionals to help prevent and correct such problems. Two common means of providing mental health care in the workplace are employee assistance programs and problem-solving seminars.

Employee assistance programs, mental health services made available by a place of business, are run either by mental health professionals who work directly for a company or by outside mental health agencies (Pomaki et al., 2012; Merrick et al., 2011; Armour, 2006). Companies publicize such programs at the work site, educate workers about psychological dysfunctioning, and teach supervisors how to identify workers who are having psychological problems. Business leaders believe that employee assistance programs save them money in the long run by preventing psychological problems from interfering with work performance and by reducing employee insurance claims, although these beliefs have not undergone extensive testing (Wang, 2007).

employee assistance program A mental health program offered by a business to its employees.

employee assistance program A mental health program offered by a business to its employees.

Stress-reduction and problem-solving seminars are workshops or group sessions in which mental health professionals teach employees techniques for coping, solving problems, and handling and reducing stress (Ashcraft, 2012; Daw, 2001). Programs of this kind are just as likely to be aimed at high-level executives as at assembly-line workers. Often employees are required to attend such workshops, which may run for several days, and are given time off from their jobs to do so.

stress-reduction and problem-solving seminar A workshop or series of group sessions offered by a business, in which mental health professionals teach employees how to cope with and solve problems and reduce stress.

stress-reduction and problem-solving seminar A workshop or series of group sessions offered by a business, in which mental health professionals teach employees how to cope with and solve problems and reduce stress.

The Economics of Mental Health

You have already seen how economic decisions by the government may influence the clinical field’s treatment of people with severe mental disorders. For example, the desire of the state and federal governments to reduce costs was an important consideration in the country’s deinstitutionalization movement, which contributed to the premature release of hospital patients into the community. Economic decisions by government agencies may affect other kinds of clients and treatment programs as well.

As you read in Chapter 15, government funding for services to people with psychological disorders has risen sharply over the past five decades, from $1 billion in 1963 to around $171 billion today (Rampell, 2013; Gill, 2010; Redick et al., 1992). Around 30 percent of that money is spent on prescription drugs, but much of the rest is targeted for income support, housing subsidies, and other such expenses rather than direct mental health services (Feldman et al., 2014; Covell et al., 2011). The result is that government funding for mental health services is, in fact, insufficient. People with severe mental disorders are hit hardest by the funding shortage. The number of people on waiting lists for community-based services grew from 200,000 in 2002 to 393,000 in 2008 (Daly, 2010), and that number has continued to rise in recent years.

BETWEEN THE LINES

Business and Mental Health

Between 2009 and 2012, U.S. pharmaceutical companies paid an estimated $4 billion to physicians for promotional speaking, research, consulting, travel, and meals. Half of the top earners were psychiatrists.

Page 659

Government funding currently covers around two-thirds of all mental health services, leaving a mental health expense of tens of billions of dollars for individual patients and their private insurance companies (Rampell, 2013; Nordal, 2010; Mark et al., 2008, 2005). This large economic role of private insurance companies has had a significant effect on the way clinicians go about their work. As you’ll remember from Chapter 1, to reduce their expenses, most of these companies have developed managed care programs, in which the insurance company determines which therapists clients may choose from, the cost of sessions, and the number of sessions for which a client may be reimbursed (Lustig et al., 2013; Turner, 2013; Domino, 2012). These and other insurance plans may also control expenses through the use of peer review systems, in which clinicians who work for the insurance company periodically review a client’s treatment program and recommend that insurance benefits be either continued or stopped. Typically, insurers require reports or session notes from the therapist, often including intimate personal information about the patient.

managed care program An insurance program in which the insurance company decides the cost, method, provider, and length of treatment.

managed care program An insurance program in which the insurance company decides the cost, method, provider, and length of treatment.

peer review system A system by which clinicians paid by an insurance company may periodically review a patient’s progress and recommend the continuation or termination of insurance benefits.

peer review system A system by which clinicians paid by an insurance company may periodically review a patient’s progress and recommend the continuation or termination of insurance benefits.

What are the costs to clients and practitioners when insurance companies make decisions about the methods, frequency, and duration of treatment?

As you also read in Chapter 1, many therapists and clients dislike managed care programs and peer reviews (Lustig et al., 2013; Turner, 2013; Scheid, 2010). They believe that the reports required of therapists breach confidentiality, even when efforts are made to protect anonymity, and that the importance of therapy in a given case is sometimes difficult to convey in a brief report. They also argue that the priorities of managed care programs inevitably shorten therapy, even if longer-term treatment would be advisable in particular cases. The priorities may also favor treatments that offer short-term results (for example, drug therapy) over more costly approaches that might yield more promising long-term improvement. As in the medical field, there are disturbing stories about patients who are prematurely cut off from mental health services by their managed care programs. In short, many clinicians fear that the current system amounts to regulation of therapy by insurance companies rather than by therapists.

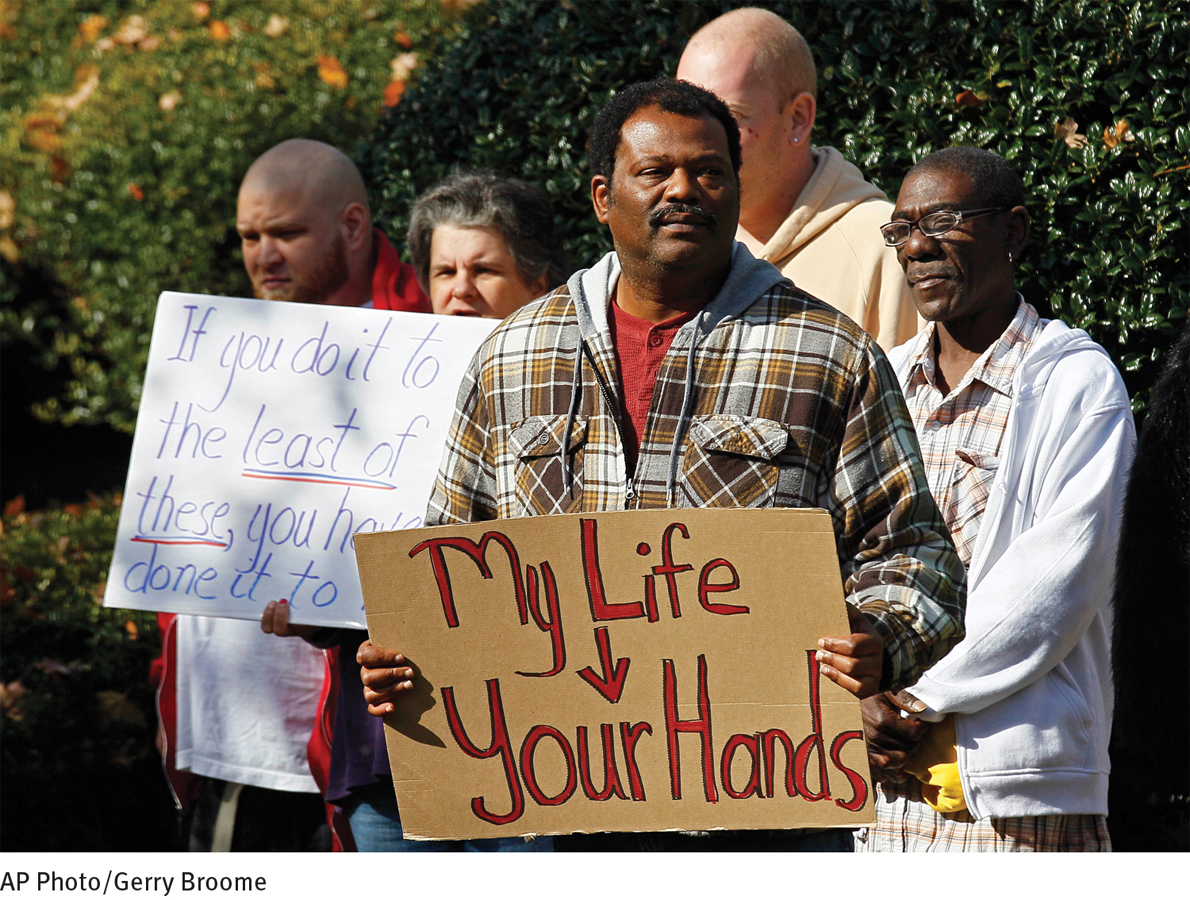

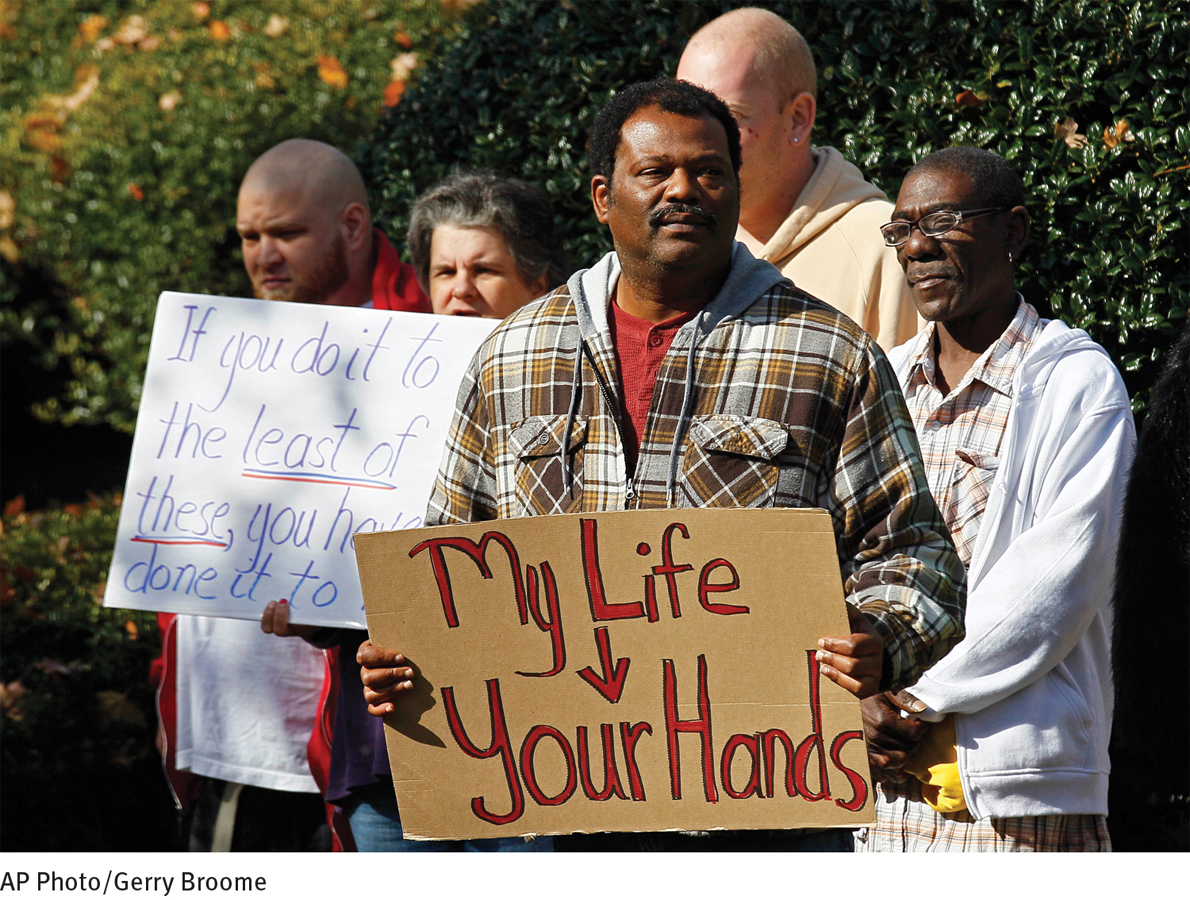

Caught in an economic spiral Group home residents and mental health advocates rally at the legislative office building in Raleigh, North Carolina, to protest a Medicaid payment law change. This change could result in residents with severe mental disorders losing their group homes and having nowhere to live.

Yet another major problem with insurance coverage in the United States—both managed care and other kinds of insurance programs—is that reimbursements for mental disorders tend to be lower than those for medical disorders, placing people with psychological difficulties at a distinct disadvantage (Abelson, 2013). As you have read, the government has tried to address this problem in recent years (see page 22). In 2008 Congress passed a federal parity law that directed insurance companies to provide equal coverage for mental and medical problems. In 2013, the Departments of Health and Human Services, Labor, and Treasury jointly issued a federal regulation that defined the principles of parity more clearly, and in 2014 the mental health provisions of the Affordable Care Act (ACA), commonly known as “Obamacare,” went into effect and extended the reach of the 2013 regulations still further (SAMHSA, 2014; Calmes & Pear, 2013; Pear, 2013). For example, the ACA designates mental health care as one of 10 types of “essential health benefits” that must be provided by all insurers. It further requires all health plans to provide preventive mental health services at no additional cost to clients and to allow new and continued membership to people with preexisting mental conditions. All of this is promising, but it is not yet clear whether such provisions will result in significantly better treatment for people with psychological problems.

Page 660

employee assistance program A mental health program offered by a business to its employees.

employee assistance program A mental health program offered by a business to its employees. stress-

stress- managed care program An insurance program in which the insurance company decides the cost, method, provider, and length of treatment.

managed care program An insurance program in which the insurance company decides the cost, method, provider, and length of treatment. peer review system A system by which clinicians paid by an insurance company may periodically review a patient’s progress and recommend the continuation or termination of insurance benefits.

peer review system A system by which clinicians paid by an insurance company may periodically review a patient’s progress and recommend the continuation or termination of insurance benefits.