19.4 Technology and Mental Health

As you have seen throughout this book, today’s ever-

New Triggers for Psychopathology

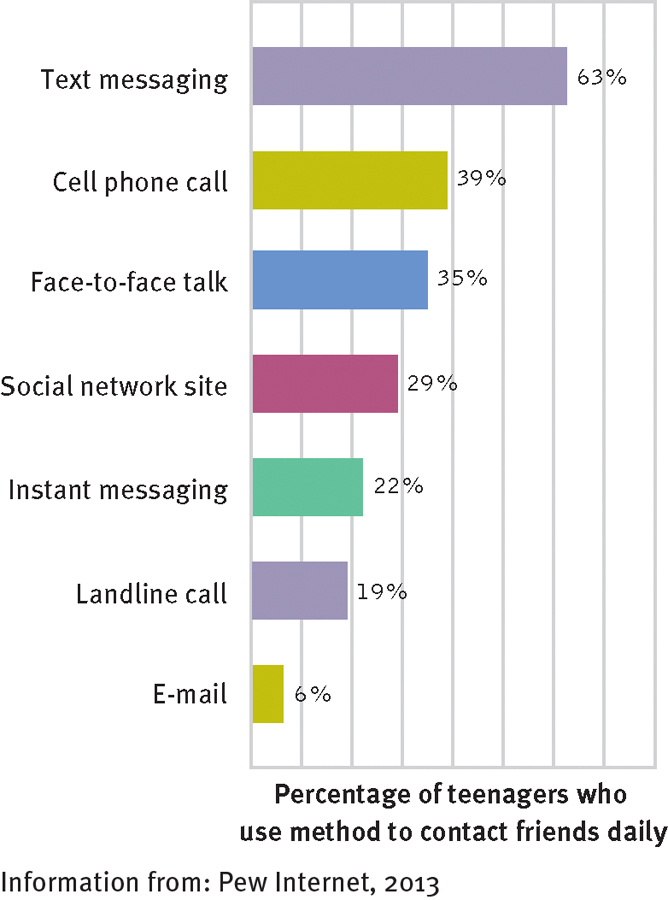

How do today’s teenagers connect each day with their friends?

A large survey of American teenagers reveals that 63 percent of teenagers use text messaging each day to connect with their friends, 35 percent talk face-

Our digital world provides new triggers for the expression of abnormal behavior. Many people who grapple with gambling disorder, for example, have found the ready availability of Internet gambling to be all too inviting (see page 419). Social networks, texting, and the Internet have become convenient tools for those who wish to stalk or bully others, express sexual exhibitionism, pursue pedophilic desires, or satisfy other paraphilias (see pages 565–

There is a growing recognition among clinical practitioners and researchers that social networking can contribute to psychological dysfunctioning in certain cases. On the positive side, research suggests that social network users in general maintain more close relationships and receive more social support than other people do (Hampton et al., 2011; Rainie et al., 2011). On the negative side, studies indicate that social networking sites may provide a new venue for peer pressure and social anxiety in some adolescents (Charles, 2011). The sites may, for example, cause some people to develop fears that others in their network will exclude them socially (see Figure 19-3). Similarly, clinicians worry that sites such as Facebook may lead shy or socially anxious people to withdraw from valuable face-

New Forms of Psychopathology

Beyond providing new triggers for abnormal behavior, research indicates that today’s technology also is helping to produce new psychological disorders. One such disorder, sometimes called Internet addiction, is marked by excessive and dysfunctional levels of texting, tweeting, networking, Internet browsing, e-

MindTech

New Ethics for a Digital Age

The American Psychological Association’s code of ethics states that psychologists who operate on the Internet (offer cybertherapy, for example) are bound by the same ethical requirements as those who operate more conventionally. That seems reasonable enough, except for one thing: Operating online opens up a world of brand-

Two leading clinical theorists, Kenneth Pope and Danny Wedding (2014), have spent the last decade compiling a list of ethical dilemmas and nightmares that can emerge as a by-

Many therapists believe that because they do not conduct cybertherapy, they are untouched by digital concerns. Yet those same therapists likely use computers to handle their clinical data—

A laptop containing confidential patient information is hacked or is stolen from an office or car trunk.

A virus, worm, or other kind of malware infects a therapist’s computer and uploads confidential files to a Web site or to everyone listed in his or her address book.

Someone reads a therapist’s laptop monitor—

and obtains confidential information— while sitting next to the therapist in an airport or on a flight. A therapist e-

mails a message containing confidential client information to a colleague, but accidentally sends it to the wrong e- mail address. A therapist sells a computer, not realizing that confidential information is still recoverable because a truly thorough form of scrubbing was not used.

What other ethical concerns or problems might emerge as a result of the mental health field’s increasing use of new technologies?

The digital age in which therapists treat clients presents many new ethical concerns and potential problems. Certainly, the field’s code of ethics must address these issues sooner rather than later. So too must each individual therapist. As Pope and Wedding (2014) point out, “When we use digital devices to handle the most sensitive and private information about our clients, we must remember to live up to an ancient precept: First, do no harm.” ![]()

Similarly, the Internet has brought a new exhibitionistic feature to certain kinds of abnormal behavior. For example, as you read in Chapter 9 (see page 288), a growing number of people now use YouTube to post videos of themselves engaging in self-

Cybertherapy

As you have seen throughout this textbook, cybertherapy is growing as a treatment option by leaps and bounds (Carrard et al., 2011; Pope & Vasquez, 2011). It takes such forms as long-

Unfortunately, as you have read, the cybertherapy movement also has some key limitations and problems. Along with the wealth of mental health information now available online comes an enormous amount of misinformation about psychological problems and their treatments, offered by people and sites that are far from knowledgeable (see page 75). The issue of quality control is also a major problem for Internet-

Clearly, the growing impact of technological change on the mental health field presents formidable challenges for clinicians and researchers alike. Few of the technological applications discussed throughout this book are well understood, and few have been subjected to comprehensive research. Yet, as we mentioned earlier, the relationship between technology and mental health is expected to grow precipitously in the coming years. It behooves everyone in the field to understand and be ready for this growth and its implications.

MediaSpeak

“Mad Pride” Fights a Stigma

By Gabrielle Glaser, The New York Times, May 11, 2008

In the YouTube video, Liz Spikol is smiling and animated, the light glinting off her large hoop earrings. Deadpan, she holds up a diaper. It is not, she explains, a hygienic item for a giantess, but rather a prop to illustrate how much control people lose when they undergo electroconvulsive therapy, or ECT, as she did 12 years ago.

In other videos and blog postings, Ms. Spikol, a 39-

In lectures across the country, Elyn Saks, a law professor and associate dean at the University of Southern California, recounts the florid visions she has experienced during her lifelong battle with schizophrenia—

Like many Americans who have severe forms of mental illness such as schizophrenia and bipolar disorder, Ms. Saks and Ms. Spikol are speaking candidly and publicly about their demons. Their frank talk is part of a conversation about mental illness (or as some prefer to put it, “extreme mental states”) that stretches from college campuses to community health centers, from YouTube to online forums.

“Until now, the acceptance of mental illness has pretty much stopped at depression,” said Charles Barber, a lecturer in psychiatry at the Yale School of Medicine. “But a newer generation, fueled by the Internet and other sophisticated delivery systems, is saying, ‘We deserve to be heard, too.’”

In what ways might the stigma of having a severe mental disorder be different from the stigma tied to nonmainstream sexual orientations?

Just as gay-

Ms. Spikol writes about her experiences with bipolar disorder in The Philadelphia Weekly, and posts videos on her blog, the Trouble With Spikol…. Thousands have watched her joke about her weight gain and loss of libido, and her giggle-

Ms. Saks, the U.S.C. professor, who recently published a memoir, “The Center Cannot Hold: My Journey Through Madness,” has come to accept her illness. She manages her symptoms with a regimen that includes psychoanalysis and medication. But stigma, she said, is never far away. She said she waited until she had tenure at U.S.C. before going public with her experience…. Ms. Saks said she hopes to help others in her position, find tolerance, especially those with fewer resources. “I have the kind of life that anybody, mentally ill or not, would want: a good place to live, nice friends, loved ones,” she said. “For an unlucky person,” Ms. Saks said, “I’m very lucky.”

May 11, 2008, “‘Mad Pride’ Fights a Stigma” by Gabrielle Glaser. From The New York Times 5/11/2008, © 2008 The New York Times. All rights reserved. Used by permission and protected by the copyright laws of the United States. The printing, copying, redistribution, or retransmission of this content without express written permission is prohibited.