1.1 What Is Psychological Abnormality?

Although their general goals are similar to those of other scientific professionals, clinical scientists and practitioners face problems that make their work especially difficult. One of the most troubling is that psychological abnormality is very hard to define. Consider once again Johanne and Alberto. Why are we so ready to call their responses abnormal?

While many definitions of abnormality have been proposed over the years, none has won total acceptance (Bergner & Bunford, 2014; Pierre, 2010). Still, most of the definitions have certain features in common, often called “the four Ds”: deviance, distress, dysfunction, and danger. That is, patterns of psychological abnormality are typically deviant (different, extreme, unusual, perhaps even bizarre), distressing (unpleasant and upsetting to the person), dysfunctional (interfering with the person’s ability to conduct daily activities in a constructive way), and possibly dangerous. This definition offers a useful starting point from which to explore the phenomena of psychological abnormality. As you will see, however, it has key limitations.

Deviance

Abnormal psychological functioning is deviant, but deviant from what? Johanne’s and Alberto’s behaviors, thoughts, and emotions are different from those that are considered normal in our place and time. We do not expect people to cry themselves to sleep each night, hate the world, wish themselves dead, or obey voices that no one else hears.

In short, abnormal behavior, thoughts, and emotions are those that differ markedly from a society’s ideas about proper functioning. Each society establishes norms—stated and unstated rules for proper conduct. Behavior that breaks legal norms is considered to be criminal. Behavior, thoughts, and emotions that break norms of psychological functioning are called abnormal.

norms A society’s stated and unstated rules for proper conduct.

norms A society’s stated and unstated rules for proper conduct.

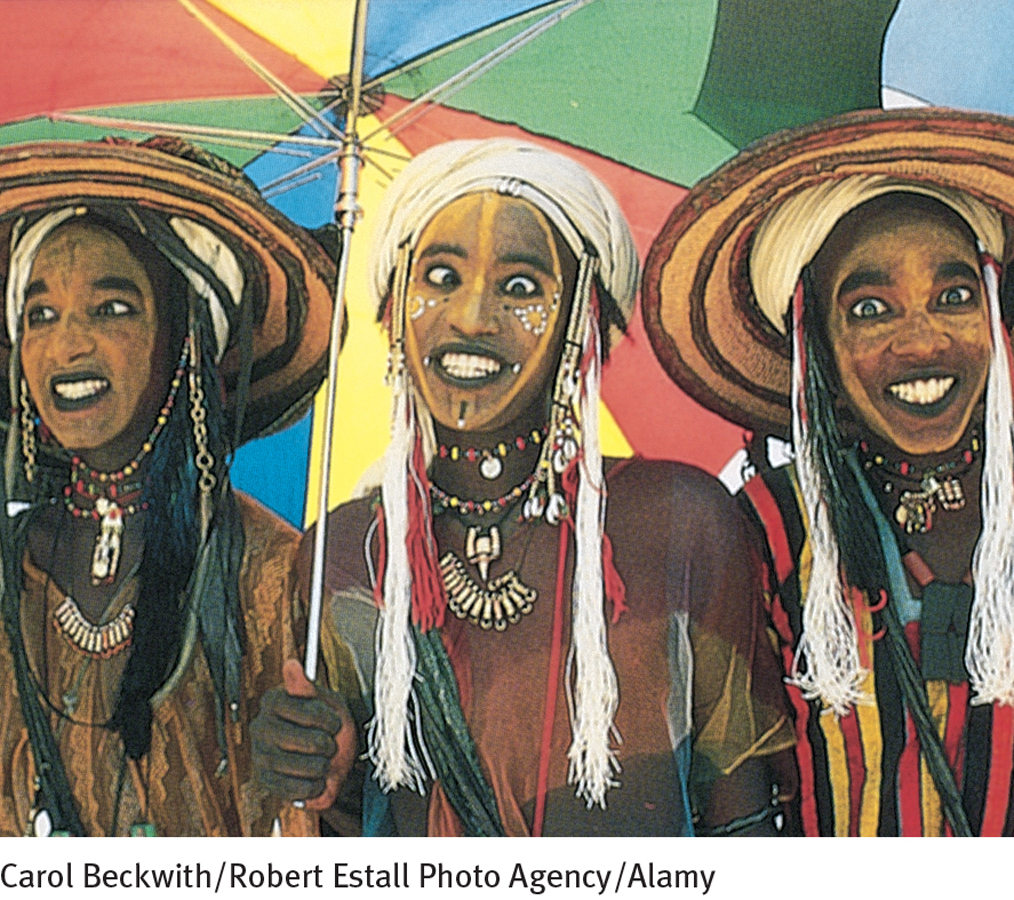

Judgments about what constitutes abnormality vary from society to society. A society’s norms grow from its particular culture—its history, values, institutions, habits, skills, technology, and arts. A society that values competition and assertiveness may accept aggressive behavior, whereas one that emphasizes cooperation and gentleness may consider aggressive behavior unacceptable and even abnormal. A society’s values may also change over time, causing its views of what is psychologically abnormal to change as well. In Western society, for example, a woman seeking the power of running a major corporation or indeed of leading the country would have been considered inappropriate and even delusional a hundred years ago. Today the same behavior is valued.

culture A people’s common history, values, institutions, habits, skills, technology, and arts.

culture A people’s common history, values, institutions, habits, skills, technology, and arts.

Judgments about what constitutes abnormality depend on specific circumstances as well as on cultural norms. What if, for example, we were to learn that Johanne is a citizen of Haiti and that her desperate unhappiness began in the days, weeks, and months following the massive earthquake that struck her country, already the poorest country in the Western hemisphere, on January 12, 2010? The quake, one of the worst natural disasters in history, killed 250,000 Haitians, left 1.5 million homeless, and destroyed most of the country’s business establishments and educational institutions. Half of Haiti’s homes and buildings were immediately turned into rubble, and its electricity and other forms of power disappeared. Tent cities replaced homes for most people. Over the next few months, a devastating hurricane, an outbreak of cholera, and violent political protests brought still more death and destruction to the people of Haiti (Granitz, 2014; MCEER, 2011; Wilkinson, 2011).

In the weeks and months that followed the earthquake, Johanne came to accept that she wouldn’t get all of the help she needed and that she might never again see the friends and neighbors who had once given her life so much meaning. As she and her daughters moved from one temporary tent or hut to another throughout the country, always at risk of developing serious diseases, she gradually gave up all hope that her life would ever return to normal. The modest but happy life she and her daughters had once known was now gone, seemingly forever. In this light, Johanne’s reactions do not seem quite so inappropriate. If anything is abnormal here, it is her situation. Many human experiences produce intense reactions—

Distress

Even functioning that is considered unusual does not necessarily qualify as abnormal. According to many clinical theorists, behavior, ideas, or emotions usually have to cause distress before they can be labeled abnormal. Consider the Ice Breakers, a group of people in Michigan who go swimming in lakes throughout the state every weekend from November through February. The colder the weather, the better they like it. One man, a member of the group for 17 years, says he loves the challenge of human against nature. A 37-

BETWEEN THE LINES

In Their Words

“I became insane, with long intervals of horrible sanity.”

Edgar Allen Poe

“I can calculate the motion of heavenly bodies but not the madness of people.”

Sir Isaac Newton

Certainly these people are different from most of us, but is their behavior abnormal? Far from experiencing distress, they feel energized and challenged. Their positive feelings must cause us to hesitate before we decide that they are functioning abnormally.

Should we conclude, then, that feelings of distress must always be present before a person’s functioning can be considered abnormal? Not necessarily. Some people who function abnormally maintain a positive frame of mind. Consider once again Alberto, the young man who hears mysterious voices. Alberto does experience distress over the coming invasion and the life changes he feels forced to make. But what if he enjoyed listening to the voices, felt honored to be chosen, loved sending out warnings on the Internet, and looked forward to saving the world? Shouldn’t we still regard his functioning as abnormal?

Dysfunction

Abnormal behavior tends to be dysfunctional; that is, it interferes with daily functioning (Bergner & Bunford, 2014). It so upsets, distracts, or confuses people that they cannot care for themselves properly, participate in ordinary social interactions, or work productively. Alberto, for example, has quit his job, left his family, and prepared to withdraw from the productive life he once led.

Here again one’s culture plays a role in the definition of abnormality. Our society holds that it is important to carry out daily activities in an effective manner. Thus Alberto’s behavior is likely to be regarded as abnormal and undesirable, whereas that of the Ice Breakers, who continue to perform well in their jobs and enjoy fulfilling relationships, would probably be considered simply unusual.

Dysfunction alone, though, does not necessarily indicate psychological abnormality. Some people (Gandhi or Cesar Chavez, for example) fast or in other ways deprive themselves of things they need as a means of protesting social injustice. Far from receiving a clinical label of some kind, they are widely viewed as admirable people—

Danger

Perhaps the ultimate in psychological dysfunctioning is behavior that becomes dangerous to oneself or others. Individuals whose behavior is consistently careless, hostile, or confused may be placing themselves or those around them at risk. Alberto, for example, seems to be endangering both himself, with his diet, and others, with his buildup of arms and ammunition.

Although danger is often cited as a feature of abnormal psychological functioning, research suggests that it is actually the exception rather than the rule (Stuber et al., 2014; Jorm et al., 2012). Despite powerful misconceptions, most people struggling with anxiety, depression, and even bizarre thinking pose no immediate danger to themselves or to anyone else.

The Elusive Nature of Abnormality

Efforts to define psychological abnormality typically raise as many questions as they answer. Ultimately, a society selects general criteria for defining abnormality and then uses those criteria to judge particular cases.

One clinical theorist, Thomas Szasz (1920–

What behaviors fit the criteria of deviant, distressful, dysfunctional, or dangerous but would not be considered abnormal by most people?

Even if we assume that psychological abnormality is a valid concept and that it can indeed be defined, we may be unable to apply our definition consistently. If a behavior—

PsychWatch

Marching to a Different Drummer: Eccentrics

Writer James Joyce always carried a tiny pair of lady’s bloomers, which he waved in the air to show approval.

Benjamin Franklin took “air baths” for his health, sitting naked in front of an open window.

Alexander Graham Bell covered the windows of his house to keep out the rays of the full moon. He also tried to teach his dog how to talk.

Writer D. H. Lawrence enjoyed removing his clothes and climbing mulberry trees.

These famous persons have been called eccentrics. The dictionary defines an eccentric as a person who deviates from common behavior patterns or displays odd or whimsical behavior. But how can we separate a psychologically healthy person who has unusual habits from a person whose oddness is a symptom of psychopathology? Little research has been done on eccentrics, but a few studies offer some insights (Stares, 2005; Pickover, 1999; Weeks & James, 1995).

Researcher David Weeks studied 1,000 eccentrics and estimated that as many as 1 in 5,000 persons may be “classic, full-

Weeks suggests that eccentrics do not typically suffer from mental disorders. Whereas the unusual behavior of persons with mental disorders is thrust upon them and usually causes them suffering, eccentricity is chosen freely and provides pleasure. In short, “Eccentrics know they’re different and glory in it” (Weeks & James, 1995, p. 14). Similarly, the thought processes of eccentrics are not severely disrupted and do not leave these persons dysfunctional. In fact, Weeks found that eccentrics in his study actually had fewer emotional problems than individuals in the general population. Perhaps being an “original” is good for mental health.

Conversely, a society may have trouble separating an abnormality that requires intervention from an eccentricity, an unusual pattern with which others have no right to interfere. From time to time we see or hear about people who behave in ways we consider strange, such as a man who lives alone with two dozen cats and rarely talks to other people. The behavior of such people is deviant, and it may well be distressful and dysfunctional, yet many professionals think of it as eccentric rather than abnormal (see PsychWatch above).

In short, while we may agree to define psychological abnormalities as patterns of functioning that are deviant, distressful, dysfunctional, and sometimes dangerous, we should be clear that these criteria are often vague and subjective. In turn, few of the current categories of abnormality that you will meet in this book are as clearcut as they may seem, and most continue to be debated by clinicians.