2.1 What Do Clinical Researchers Do?

Clinical researchers, also called clinical scientists, try to discover universal laws, or principles, of abnormal psychological functioning. They search for a general, or nomothetic, understanding of the nature, causes, and treatments of abnormality (“nomothetic” is derived from the Greek nomothetis, “lawgiver”) (DeMatteo et al., 2010). They do not typically assess, diagnose, or treat individual clients; that is the job of clinical practitioners, who seek an idiographic, or individualistic, understanding of abnormal behavior. You will read about the work of practitioners in later chapters.

nomothetic understanding A general understanding of the nature, causes, and treatments of abnormal functioning, in the form of laws or principles.

nomothetic understanding A general understanding of the nature, causes, and treatments of abnormal functioning, in the form of laws or principles.

To gain a nomothetic understanding of abnormal psychology, clinical researchers, like scientists in other fields, use the scientific method—that is, they collect and evaluate information through careful observations. These observations in turn enable them to pinpoint and explain relationships between variables. Simply stated, a variable is any characteristic or event that can vary, whether from time to time, from place to place, or from person to person. Age, sex, and race are human variables. So are eye color, occupation, and social status. Clinical researchers are interested in variables such as childhood upsets, present life experiences, moods, social functioning, and responses to treatment. They try to determine whether two or more such variables change together and whether a change in one variable causes a change in another. Will the death of a parent cause a child to become depressed? If so, will a given treatment reduce that depression?

scientific method The process of systematically gathering and evaluating information through careful observations to understand a phenomenon.

scientific method The process of systematically gathering and evaluating information through careful observations to understand a phenomenon.

PsychWatch

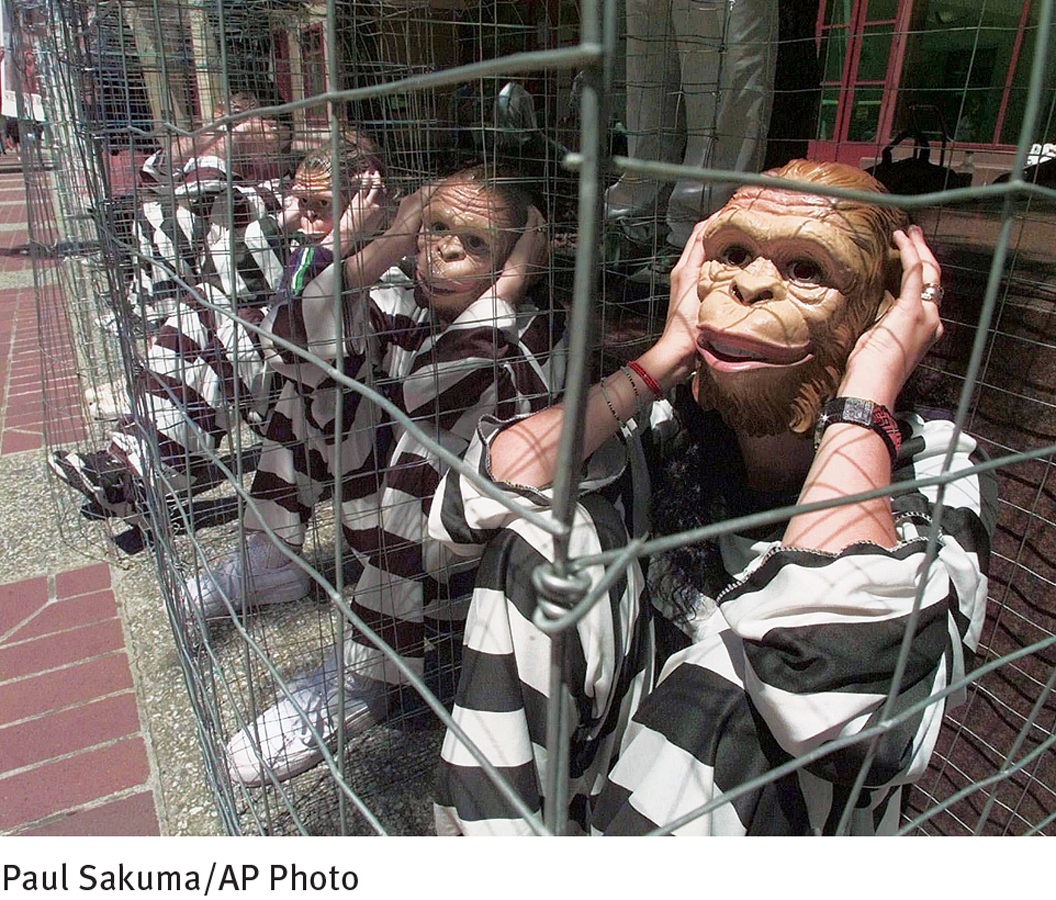

Animals Have Rights

For years, researchers have learned much about abnormal human behavior from experiments with animals (Hawkes, 2013). Animals have been shocked, prematurely separated from their parents, and starved. They have had their brains surgically changed and have even been killed, or “sacrificed,” so that researchers could autopsy them. It is estimated that medical animal research (for example, cardiovascular research) has helped increase the life expectancy of humans by almost 24 years. Similarly, animal research has been key to the development of many medications for psychological disorders, leading to a savings of hundreds of billions of dollars every year in the United States alone (Henderson et al., 2013; Shields, 2010; Lasker Foundation, 2000). Nevertheless, concerns remain: Are such actions always ethically acceptable?

Animal rights activists say no (Grimm, 2013; McCance, 2011; Fellenz, 2007). They have called such undertakings cruel and unnecessary and have fought many forms of animal research with legal protests and demonstrations. Some have even harassed scientists and vandalized their labs (Conn & Rantin, 2010). In turn, some researchers have accused activists of caring more about animals than about human beings. In response to this controversy, a number of state courts, government agencies, and the American Psychological Association have issued rules and guidelines for animal research. But the battle still goes on.

Where does the public stand on this issue (Hobson-

Such questions cannot be answered by logic alone because scientists, like all human beings, frequently make errors in thinking. Thus, clinical researchers must depend mainly on three methods of investigation: the case study, which typically is focused on one individual, and the correlational method and experimental method, approaches that are usually used to gather information about many individuals. Each is best suited to certain kinds of circumstances and questions. As a group, these methods enable scientists to form and test hypotheses, or hunches, that certain variables are related in certain ways—

hypothesis A hunch or prediction that certain variables are related in certain ways.

hypothesis A hunch or prediction that certain variables are related in certain ways.