2.2 The Case Study

A case study is a detailed description of a person’s life and psychological problems. It describes the person’s history, present circumstances, and symptoms. It may also include speculation about why the problems developed, and it may describe the person’s treatment (Yin, 2013; Lee, Mishna, & Brennenstuhl, 2010).

case study A detailed account of a person’s life and psychological problems.

case study A detailed account of a person’s life and psychological problems.

In his famous case study of Little Hans (1909), Sigmund Freud discusses a 4-

BETWEEN THE LINES

All About Freud

Freud’s parents often favored Sigmund over his siblings.

Freud’s fee for one session of therapy was $20.

For almost 40 years, Freud treated patients 10 hours per day, 5 or 6 days per week.

Freud’s four sisters died in Nazi concentration camps.

Freud was nominated for the Nobel Prize in 12 different years, but never won.

In 1929, the Nobel Committee for Medicine hired a consultant who concluded that Freud’s work was of no scientific value.

(Nobel Media, 2014; Cherry, 2010; Hess, 2009; Gay, 2006, 1999; Jacobs, 2003)

One day while Hans was in the street he was seized with an attack of morbid anxiety…. [Hans’s father wrote:] “He began to cry and asked to be taken home…. In the evening he grew visibly frightened; he cried and could not be separated from his mother…. [When taken for a walk the next day] again he began to cry, did not want to start, and was frightened…. On the way back from Schönbrunn he said to his mother, after much internal struggling: ‘I was afraid a horse would bite me.’ … In the evening he … had another attack similar to that of the previous evening….”

But the beginnings of this psychological situation go back further still…. The first reports of Hans date from a period when he was not quite three years old. At that time, by means of various remarks and questions, he was showing a quite peculiarly lively interest in that portion of his body which he used to describe as his “widdler” [his word for penis]….

When he was three and a half his mother found him with his hand to his penis. She threatened him in these words: “If you do that, I shall send for Dr. A. to cut off your widdler. And then what’ll you widdle with?” … This was the occasion of his acquiring [a] “castration complex.” …

[At the age of four, Hans entered] a state of intensified sexual excitement, the object of which was his mother. The intensity of this excitement was shown by … two attempts at seducing his mother. [One such attempt, occurring just before the outbreak of his anxiety, was described by his father:] “This morning Hans was given his usual daily bath by his mother and afterwards dried and powdered. As his mother was powdering round his penis and taking care not to touch it, Hans said: ‘Why don’t you put your finger there?’ … “

… The father and son visited me during my consulting hours…. Certain details which I now learnt—

By enlightening Hans on this subject I had cleared away his most powerful resistance…. [T]he little patient summoned up courage to describe the details of his phobia, and soon began to take an active share in the conduct of the analysis.

… It was only then that we learnt [that Hans] was not only afraid of horses biting him—

It was at this stage of the analysis that he recalled the event, insignificant in itself, which immediately preceded the outbreak of the illness and may no doubt be regarded as the exciting cause of the outbreak. He went for a walk with his mother, and saw a bus-

It is especially interesting … to observe the way in which the transformation of Hans’s libido into anxiety was projected on to the principal object of his phobia, on to horses. Horses interested him the most of all the large animals; playing at horses was his favorite game with the older children. I had a suspicion—

[Hans later reported] two concluding phantasies, with which his recovery was rounded off. One of them, that of [a] plumber giving him a new and … bigger widdler, was … a triumphant wish-

(Freud, 1909)

Most clinicians take notes and keep records in the course of treating their patients, and some, like Freud, further organize such notes into a formal case study to be shared with other professionals. The clues offered by a case study may help a clinician better understand or treat the person under discussion (Yin, 2013; Stricker & Trierweiler, 1995). In addition, case studies may play nomothetic roles that go far beyond the individual clinical case.

How Are Case Studies Helpful?

Case studies can be a source of new ideas about behavior and “open the way for discoveries” (Bolgar, 1965). Freud’s theory of psychoanalysis was based mainly on the patients he saw in private practice. He pored over their case studies, such as the one he wrote about Little Hans, to find what he believed to be broad psychological processes and principles of development. In addition, a case study may offer tentative support for a theory. Freud used case studies in this way as well, regarding them as evidence for the accuracy of his ideas. Conversely, case studies may serve to challenge a theory’s assumptions (Yin, 2013; Elms, 2007).

Case studies may also show the value of new therapeutic techniques or unique applications of existing techniques. The psychoanalytic principle that says patients may benefit from discussing their problems and discovering underlying psychological causes, for example, has roots in the famous case study of Anna O., presented by Freud’s collaborator Josef Breuer, a case you will read about in Chapter 3. Similarly, Freud believed that the case study of Little Hans demonstrated the therapeutic potential of a verbal approach for children as well as for adults.

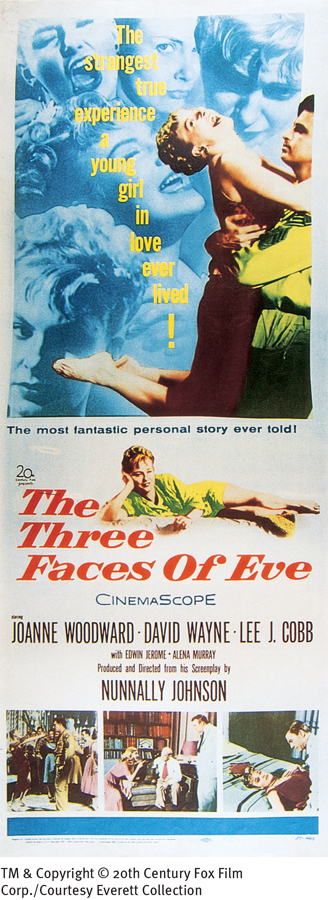

Finally, case studies may offer opportunities to study unusual problems that do not occur often enough to permit a large number of observations (Goodwin & Goodwin, 2012). For years, information about dissociative identity disorder (previously called multiple personality disorder) was based almost exclusively on case studies, such as a famous case popularly referred to as The Three Faces of Eve, a clinical account of Chris Sizemore, a woman who displayed three alternating personalities, each having a separate set of memories, preferences, and personal habits (Thigpen & Cleckley, 1957).

What Are the Limitations of Case Studies?

Case studies also have limitations (Yin, 2013; Girden & Kabacoff, 2011). First, they are reported by biased observers, that is, by therapists who have a personal stake in seeing their treatments succeed. These therapists must choose what to include in a case study, and their choices may at times be self-

Why do case studies and other anecdotal offerings influence people so much, often more than systematic research does?

internal validity The accuracy with which a study can pinpoint one factor as the cause of a phenomenon.

internal validity The accuracy with which a study can pinpoint one factor as the cause of a phenomenon.

Another problem with case studies is that they provide little basis for generalization. Even if we agree that Little Hans developed a dread of horses because he was terrified of castration and feared his father, how can we be confident that other people’s phobias are rooted in the same kinds of causes? Events or treatments that seem important in one case may be of no help at all in efforts to understand or treat others. When the findings of an investigation can be generalized beyond the immediate study, the investigation is said to have external accuracy, or external validity (Jackson, 2012). Case studies rate low on external validity, too (Goodwin & Goodwin, 2012).

external validity The degree to which the results of a study may be generalized beyond that study.

external validity The degree to which the results of a study may be generalized beyond that study.

The limitations of the case study are largely addressed by two other methods of investigation: the correlational method and the experimental method. These methods do not offer the rich detail that makes case studies so interesting, but they do help investigators draw broad conclusions about abnormality in the population at large. Thus they are now the preferred methods of clinical investigation.

Three features of the correlational and experimental methods enable clinical investigators to gain general, or nomothetic, insights: (1) The researchers typically observe many individuals (see MindTech below). That way, they can collect enough information, or data, to support a conclusion. (2) The researchers apply procedures uniformly. Other researchers can thus repeat, or replicate, a particular study to see whether it consistently gives the same findings. (3) The researchers use statistical tests to analyze the results of a study. These tests can help indicate whether broad conclusions are justified.

MindTech

A Researcher’s Paradise?

Two of the biggest problems for researchers are finding enough participants for their studies and obtaining a sufficient range of participants. Until recent years, undergraduates were the most common participants in behavioral research—

On the downside, undergraduates are a pretty homogeneous group whose behaviors and emotions do not always generalize to other groups in society (Phillips, 2011). Thus, it is probably good that the face of research recruitment is now changing. More and more researchers are turning to social networking sites—

One recent study demonstrates the power and potential of social media participant pools (Kosinski et al., 2013). In this investigation, 58,000 Facebook subscribers allowed the researchers access to their list of “likes,” and the subscribers further filled out online personality tests. The study found that information about a participant’s likes could predict with considerable accuracy his or her personality traits, level of happiness, use of addictive substances, and level of intelligence, among other variables. Similarly, other social media site studies have tested various psychological theories “about relationships, identity, self-

What a great resource, right? Not so fast. The studies above asked social media users whether they were willing to participate, but in a number of other studies, the users do not know that their posted information is being examined and tested. Inasmuch as posted information is publicly available, some researchers believe it is ethical to study that information without informing users that they are indeed being studied.

Can an argument be made that ethical standards regarding Internet use should be different from those applied in other areas of life?

Facebook and most other social media sites do not have policies prohibiting scholars from studying user profiles without permission (Rosenbloom, 2007). In contrast, the Institutional Review Boards at many research institutes have concluded that postings on social networking sites should be considered private, and they require researchers at their institutions to obtain explicit permission from social media users when network information is being examined. While this technology-![]()