2.6 Protecting Human Participants

Like the animal subjects that you read about earlier (see pages 31 and 47–48), human research participants have needs and rights that must be respected. In fact, researchers’ primary obligation is to avoid harming the human participants in their studies—physically or psychologically.

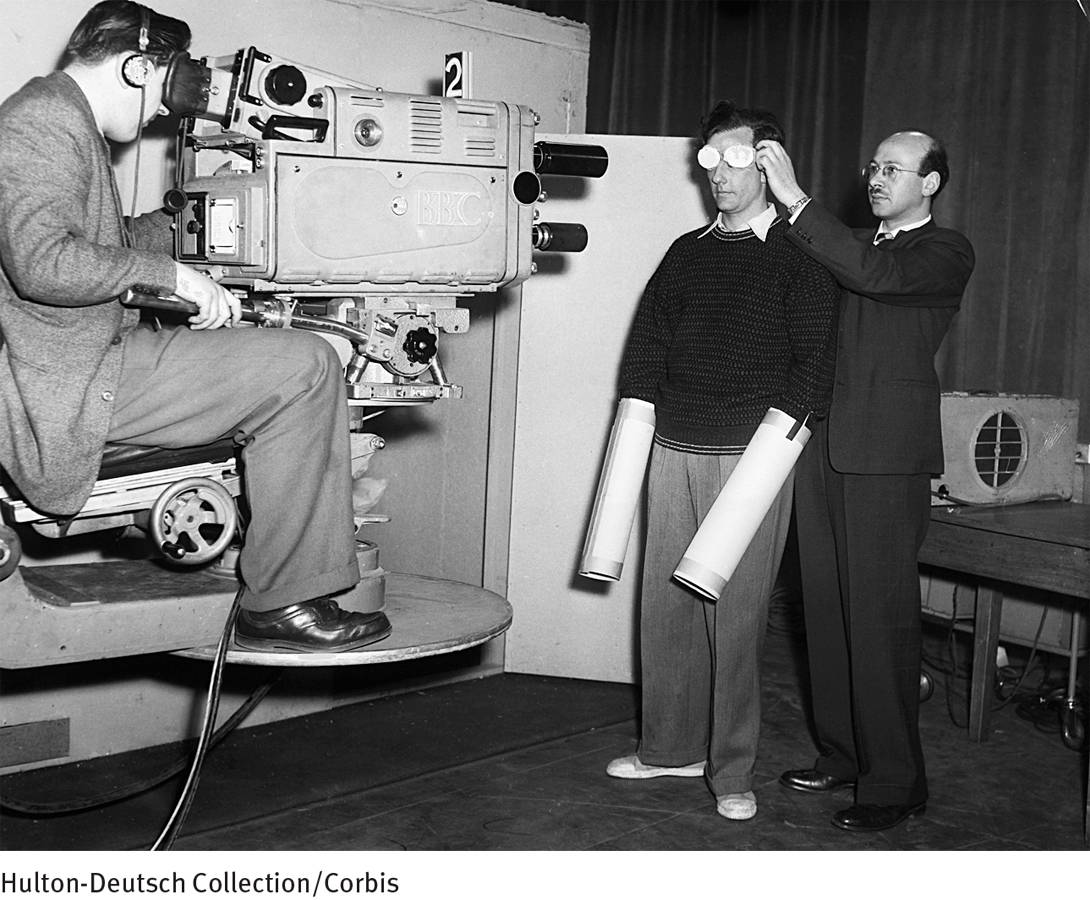

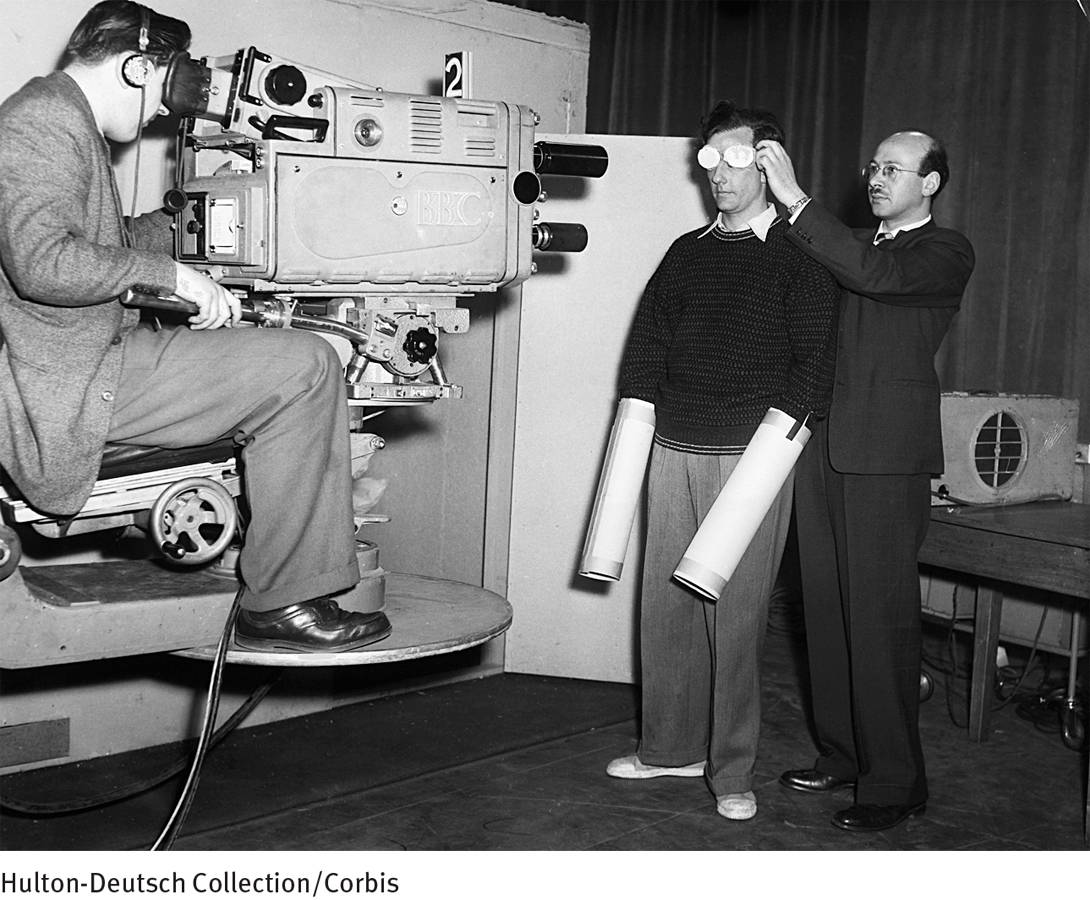

How times have changed In a 1957 study of the psychological effects of complete isolation, participants were placed in a soundproof box, wearing dark goggles, gloves, and cardboard tubes over their hands to deprive them of hearing, sight, and touch. The 25-hour study was actually televised live throughout England, an event that probably would not be permitted today, given current human research safeguards, such as participant confidentiality, informed consent, and IRB approval.

The vast majority of researchers are conscientious about fulfilling this obligation. They try to conduct studies that test their hypotheses and further scientific knowledge in a safe and respectful way. But there have been some notable exceptions to this over the years, particularly three infamous studies conducted in the mid-1900s, as you’ll see in PsychWatch below. Partly because of such exceptions, the government and the institutions in which research is conducted now take careful measures to ensure that the safety and rights of human research participants are properly protected.

Who, beyond researchers themselves, might directly watch over the rights and safety of human participants? For the past few decades, that responsibility has been given to Institutional Review Boards, or IRBs. Each research facility has an IRB—a committee of five or more members who review and monitor every study conducted at that institution, starting when the studies are first proposed. The institution may be a university, medical school, psychiatric or medical hospital, private research facility, mental health center, or the like. If research is conducted there, the institution must have an IRB, and that IRB has the responsibility and power to require changes in a proposed study as a condition of approval. If acceptable changes are not made by the researcher, then the IRB can disapprove the study altogether. Similarly, if over the course of the study, the safety or rights of the participants are placed in jeopardy, the IRB must intervene and can even stop the study if necessary. These powers are granted to IRBs (or similar ethics committees) by nations around the world. In the United States, for example, IRBs are empowered by two agencies of the federal government—the Office for Human Research Protections and the Food and Drug Administration.

Institutional Review Board (IRB) An ethics committee in a research facility that is empowered to protect the rights and safety of human research participants.

Institutional Review Board (IRB) An ethics committee in a research facility that is empowered to protect the rights and safety of human research participants.

Page 50

PsychWatch

A national disgrace In a 1997 White House ceremony, President Bill Clinton offers an official apology to 94-year-old Herman Shaw and other African American men whose syphilis went untreated by government doctors and researchers in the Tuskegee Syphilis Study.

From 1932 to 1972, the U.S. Public Health Department conducted an infamous study at the Tuskegee Institute in Alabama. The researchers wanted to follow the natural progression of untreated syphilis in impoverished African American men. The study’s participants, 399 of whom had syphilis, were given free general medical care and meals and were told they were being treated for “bad blood.” However, they were not specifically told that they had syphilis, nor were they actually treated for syphilis even after it became known in the 1940s that penicillin is an effective treatment for this disease.

From 1953 to 1963, in collaboration with the CIA, Army researchers conducted another infamous study called Project MK-ULTRA in which they gave unknowing human participants (usually soldiers) repeated doses of LSD. The goal of this study was to determine the psychological effects of LSD, but at what cost? Participants were uninformed and endangered throughout the project (Sontag, 2012; Goodwin, 2011).

And, in yet another long-term study, carried out from 1956 to 1970, medical researchers deliberately infected with hepatitis 1 of every 10 children admitted to the Willowbrook State School in New York City, an institution for persons with intellectual disability. The goal of the study was to develop a hepatitis vaccine, but again at what cost? The children were uninformed and endangered throughout the project, their parents were pressured into giving consent, and the goals of the study were not even related directly to the children’s disorders (Sontag, 2012; Goodwin, 2011; Streatfeild, 2007).

Soon after these and several other scandalous studies came to light in the 1970s, federal regulations were established to ensure that the rights of human participants, particularly those with psychological disorders, are protected in research. As a result of such regulations, every research institute in the United States now has an Institutional Review Board (IRB) that observes and protects the well-being and rights of participants in their studies (Sontag, 2012; Goldman et al., 2010; Bankert & Madur, 2006).

BETWEEN THE LINES

Today’s Most Ethically Challenged Research Designs

New Drug Studies When clinical patients are administered experimental drugs in new drug studies, they may be helped, unaffected, or damaged by the drugs.

Placebo Studies When a new drug is being tested, control participants—often people with severe disorders—may receive only a placebo drug.

Symptom-Exacerbation Studies In some studies, patients are given drugs designed to intensify their symptoms so that researchers may learn more about the biology of their disorder.

Medication-Withdrawal Studies In some studies, researchers prematurely stop medications for patients who have been symptom-free for awhile, in order to learn more about when patients can be taken off particular medications.

It turns out that protecting the rights and safety of human research participants is a complex undertaking. Thus, IRBs often are forced to conduct a kind of risk-benefit analysis in their reviews. They may, for example, approve a study that poses minimal or slight risks to participants if that “acceptable” level of risk is offset by the study’s potential benefits to society. In general, IRBs try to ensure that each study grants the following rights to its participants (NIJ, 2010):

The participants enlist voluntarily.

Before enlisting, the participants are adequately informed about what the study entails (“informed consent”).

The participants can end their participation in the study at any time.

The benefits of the study outweigh its costs/risks.

The participants are protected from physical and psychological harm.

The participants have access to information about the study.

The participants’ privacy is protected by principles such as confidentiality or anonymity.

Unfortunately, even with IRBs on the job, these rights can be in jeopardy. Consider, for example, the right of informed consent. To help ensure that participants understand what they are getting into when they enlist for a study, IRBs typically require that the individuals read and sign an “informed consent form” which spells out everything they need to know. But how clear are such forms? Not very, according to some investigations (Albala, Doyle, & Appelbaum, 2010; Mathew & McGrath, 2002; Uretsky, 1999).

Page 51

It turns out that most such forms—the very forms deemed acceptable by IRBs—are written at an advanced college level, making them incomprehensible to a large percentage of participants. In fact, fewer than half of all participants may fully understand the informed consent forms they are signing. Still other investigations indicate that only around 10 percent of human participants carefully read the informed consent forms before signing them, and only 30 percent ask questions of the researchers during the informed consent phase of their studies (CISCRP, 2013).

In short, the IRB system is flawed, much like the research undertakings it oversees. There are various reasons for this. One is that ethical principles are subtle and elusive notions that do not always translate into simple regulations and guidelines. Another reason is that ethical decisions—whether by IRB members or by researchers—are subject to differences in perspective, interpretation, decision-making style, and the like. Despite such problems and limitations, most observers agree that the creation and work of IRBs have helped improve the rights and safety of human research participants over the years. The boards may reflect an imperfect system, but they play a necessary and important role in monitoring the quality and appropriateness of research undertakings.

Institutional Review Board (IRB) An ethics committee in a research facility that is empowered to protect the rights and safety of human research participants.

Institutional Review Board (IRB) An ethics committee in a research facility that is empowered to protect the rights and safety of human research participants.