3.2 The Psychodynamic Model

The psychodynamic model is the oldest and most famous of the modern psychological models. Psychodynamic theorists believe that a person’s behavior, whether normal or abnormal, is determined largely by underlying psychological forces of which he or she is not consciously aware. These internal forces are described as dynamic—that is, they interact with one another—

Psychodynamic theorists would view Philip Berman as a person in conflict. They would want to explore his past experiences because, in their view, psychological conflicts are tied to early relationships and to traumatic experiences that occurred during childhood. Psychodynamic theories rest on the deterministic assumption that no symptom or behavior is “accidental”: All behavior is determined by past experiences. Thus Philip’s hatred for his mother, his memories of her as cruel and overbearing, the weakness of his father, and the birth of a younger brother when Philip was 10 may all be important to the understanding of his current problems.

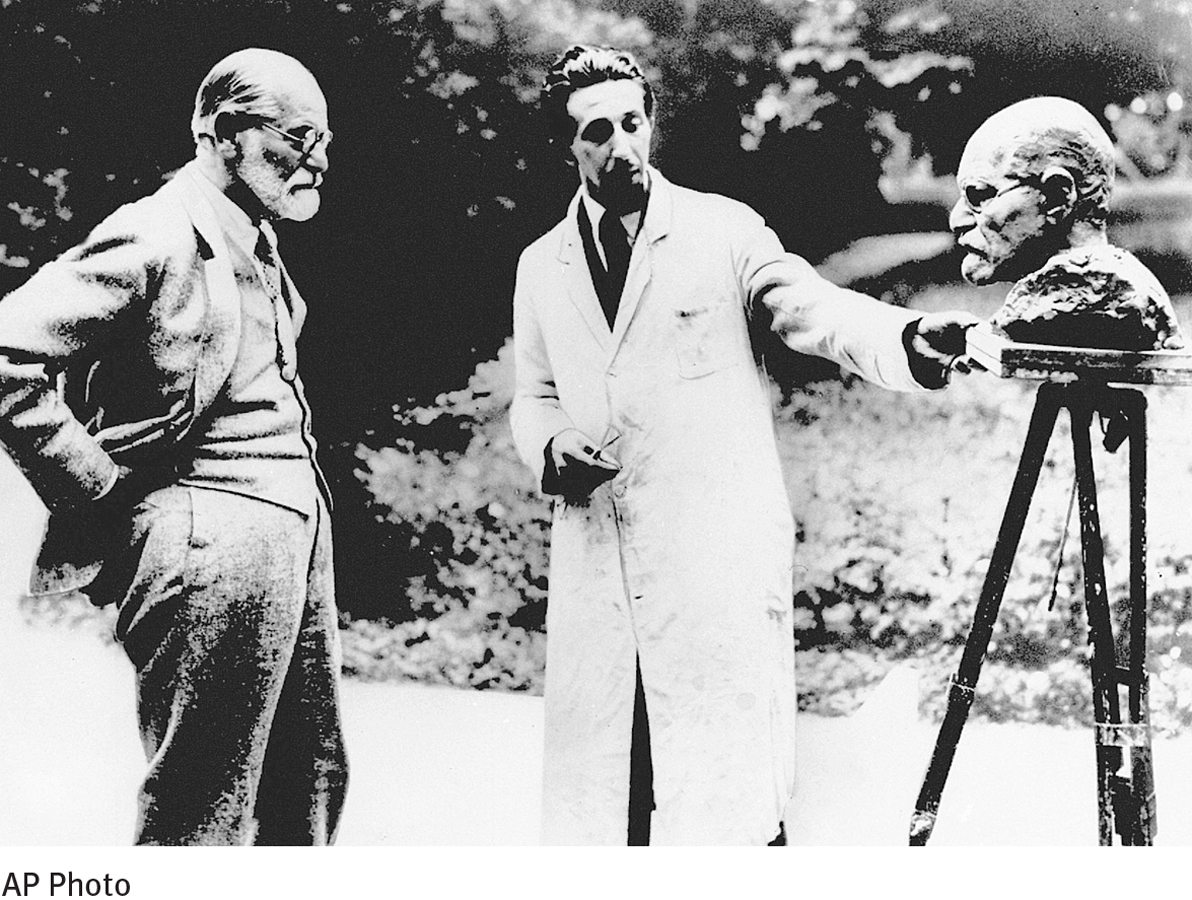

The psychodynamic model was first formulated by Viennese neurologist Sigmund Freud (1856–

Building on this early work, Freud developed the theory of psychoanalysis to explain both normal and abnormal psychological functioning as well as a corresponding method of treatment, a conversational approach also called psychoanalysis. During the early 1900s, Freud and several of his colleagues in the Vienna Psychoanalytic Society—

How Did Freud Explain Normal and Abnormal Functioning?

BETWEEN THE LINES

In Their Words

“Mental illness is so much more complicated than any pill that any mortal could invent.”

Elizabeth Wurtzel, Prozac Nation

Freud believed that three central forces shape the personality—

The IdFreud used the term id to denote instinctual needs, drives, and impulses. The id operates in accordance with the pleasure principle; that is, it always seeks gratification. Freud also believed that all id instincts tend to be sexual, noting that from the very earliest stages of life a child’s pleasure is obtained from nursing, defecating, masturbating, or engaging in other activities that he considered to have sexual ties. He further suggested that a person’s libido, or sexual energy, fuels the id.

id According to Freud, the psychological force that produces instinctual needs, drives, and impulses.

id According to Freud, the psychological force that produces instinctual needs, drives, and impulses.

The EgoDuring our early years we come to recognize that our environment will not meet every instinctual need. Our mother, for example, is not always available to do our bidding. A part of the id separates off and becomes the ego. Like the id, the ego unconsciously seeks gratification, but it does so in accordance with the reality principle, the knowledge we acquire through experience that it can be unacceptable to express our id impulses outright. The ego, employing reason, guides us to know when we can and cannot express those impulses.

ego According to Freud, the psychological force that employs reason and operates in accordance with the reality principle.

ego According to Freud, the psychological force that employs reason and operates in accordance with the reality principle.

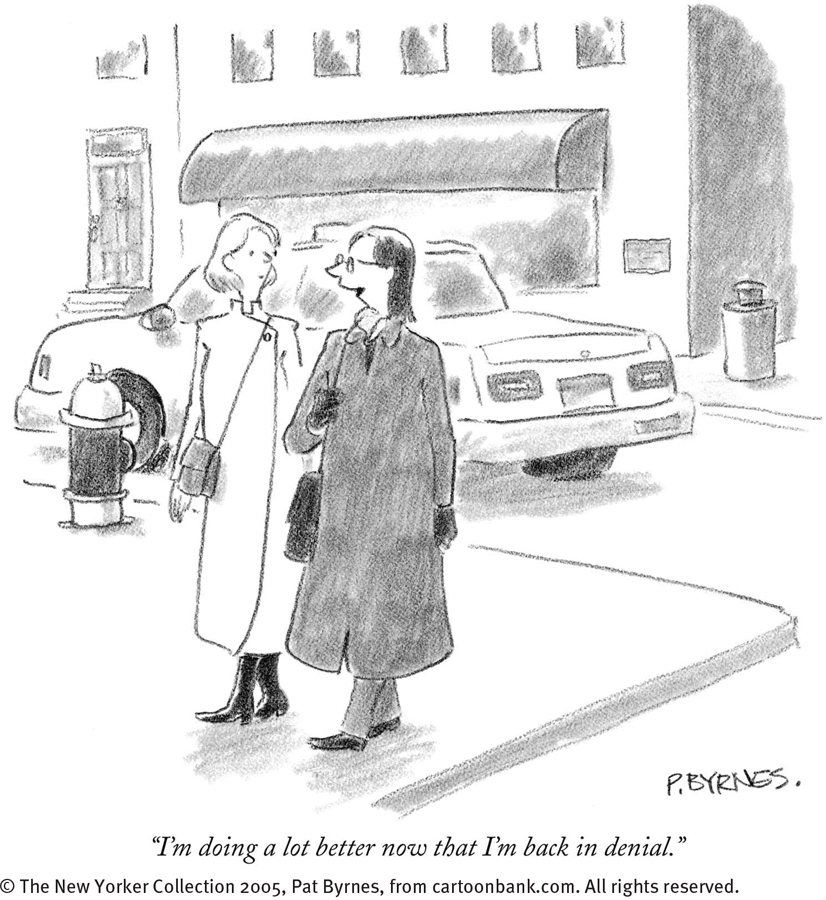

The ego develops basic strategies, called ego defense mechanisms, to control unacceptable id impulses and avoid or reduce the anxiety they arouse. The most basic defense mechanism, repression, prevents unacceptable impulses from ever reaching consciousness. There are many other ego defense mechanisms, and each of us tends to favor some over others (see Table 3-1).

ego defense mechanisms According to psychoanalytic theory, strategies developed by the ego to control unacceptable id impulses and to avoid or reduce the anxiety they arouse.

ego defense mechanisms According to psychoanalytic theory, strategies developed by the ego to control unacceptable id impulses and to avoid or reduce the anxiety they arouse.

|

Defense |

Operation |

Example |

|---|---|---|

|

Repression |

Person avoids anxiety by simply not allowing painful or dangerous thoughts to become conscious. |

An executive’s desire to run amok and attack his boss and colleagues at a board meeting is denied access to his awareness. |

|

Denial |

Person simply refuses to acknowledge the existence of an external source of anxiety. |

You are not prepared for tomorrow’s final exam, but you tell yourself that it’s not actually an important exam and that there’s no good reason not to go to a movie tonight. |

|

Projection |

Person attributes own unacceptable impulses, motives, or desires to other individuals. |

The executive who repressed his destructive desires may project his anger onto his boss and claim that it is actually the boss who is hostile. |

|

Rationalization |

Person creates a socially acceptable reason for an action that actually reflects unacceptable motives. |

A student explains away poor grades by citing the importance of the “total experience” of going to college and claiming that too much emphasis on grades would actually interfere with a well- |

|

Displacement |

Person displaces hostility away from a dangerous object and onto a safer substitute. |

After a perfect parking spot is taken by a person who cuts in front of your car, you release your pent- |

|

Intellectualization |

Person represses emotional reactions in favor of overly logical response to a problem. |

A woman who has been beaten and raped gives a detached, methodical description of the effects that such attacks may have on victims. |

|

Regression |

Person retreats from an upsetting conflict to an early developmental stage at which no one is expected to behave maturely or responsibly. |

A boy who cannot cope with the anger he feels toward his rejecting mother regresses to infantile behavior, soiling his clothes and no longer taking care of his basic needs. |

The SuperegoThe superego grows from the ego, just as the ego grows out of the id. This personality force operates by the morality principle, a sense of what is right and what is wrong. As we learn from our parents that many of our id impulses are unacceptable, we unconsciously adopt our parents’ values. Judging ourselves by their standards, we feel good when we uphold their values; conversely, when we go against them, we feel guilty. In short, we develop a conscience.

superego According to Freud, the psychological force that represents a person’s values and ideals.

superego According to Freud, the psychological force that represents a person’s values and ideals.

According to Freud, these three parts of the personality—

Freudians would therefore view Philip Berman as someone whose personality forces have a poor working relationship. His ego and superego are unable to control his id impulses, which lead him repeatedly to act in impulsive and often dangerous ways—

Developmental StagesFreud proposed that at each stage of development, from infancy to maturity, new events challenge individuals and require adjustments in their id, ego, and superego. If the adjustments are successful, they lead to personal growth. If not, the person may become fixated, or stuck, at an early stage of development. Then all subsequent development suffers, and the individual may well be headed for abnormal functioning in the future. Because parents are the key figures during the early years of life, they are often seen as the cause of improper development.

fixation According to Freud, a condition in which the id, ego, and superego do not mature properly and are frozen at an early stage of development.

fixation According to Freud, a condition in which the id, ego, and superego do not mature properly and are frozen at an early stage of development.

Freud named each stage of development after the body area that he considered most important to the child at that time. For example, he referred to the first 18 months of life as the oral stage. During this stage, children fear that the mother who feeds and comforts them will disappear. Children whose mothers consistently fail to gratify their oral needs may become fixated at the oral stage and display an “oral character” throughout their lives, one marked by extreme dependence or extreme mistrust. Such persons are particularly prone to develop depression. As you will see in later chapters, Freud linked fixations at the other stages of development—

How Do Other Psychodynamic Explanations Differ from Freud’s?

Personal and professional differences between Freud and his colleagues led to a split in the Vienna Psychoanalytic Society early in the twentieth century. Carl Jung, Alfred Adler, and others developed new theories. Although the new theories departed from Freud’s ideas in important ways, each held on to Freud’s belief that human functioning is shaped by dynamic (interacting) psychological forces. Thus all such theories, including Freud’s, are referred to as psychodynamic.

Three of today’s most influential psychodynamic theories are ego theory, self theory, and object relations theory. Ego theorists emphasize the role of the ego and consider it a more independent and powerful force than Freud did (Sharf, 2012). Self theorists, in contrast, give the greatest attention to the role of the self—the unified personality. They believe that the basic human motive is to strengthen the wholeness of the self (Dunn, 2013; Kohut, 2001, 1977). Object relations theorists propose that people are motivated mainly by a need to have relationships with others and that severe problems in the relationships between children and their caregivers may lead to abnormal development (Yun et al., 2013; Kernberg, 2005, 2001, 1997).

ego theory The psychodynamic theory that emphasizes the role of the ego and considers it an independent force.

ego theory The psychodynamic theory that emphasizes the role of the ego and considers it an independent force.

self theory The psychodynamic theory that emphasizes the role of the self—

self theory The psychodynamic theory that emphasizes the role of the self—

object relations theory The psycho-

object relations theory The psycho-

Psychodynamic Therapies

Psychodynamic therapies range from Freudian psychoanalysis to modern therapies based on self theory or object relations theory. Psychodynamic therapists seek to uncover past traumas and the inner conflicts that have resulted from them. They try to help clients resolve, or settle, those conflicts and to resume personal development.

According to most psychodynamic therapists, therapists must subtly guide therapy discussions so that the patients discover their underlying problems for themselves. To aid in the process, the therapists rely on such techniques as free association, therapist interpretation, catharsis, and working through.

Free AssociationIn psychodynamic therapies, the patient is responsible for starting and leading each discussion. The therapist tells the patient to describe any thought, feeling, or image that comes to mind, even if it seems unimportant. This practice is known as free association. The therapist expects that the patient’s associations will eventually uncover unconscious events. In the following excerpts from a famous psychodynamic case, notice how free association helps a woman to discover threatening impulses and conflicts within herself:

free association A psychodynamic technique in which the patient describes any thought, feeling, or image that comes to mind, even if it seems unimportant.

free association A psychodynamic technique in which the patient describes any thought, feeling, or image that comes to mind, even if it seems unimportant.

|

Patient: |

So I started walking, and walking, and decided to go behind the museum and walk through [New York’s] Central Park. So I walked and went through a back field and felt very excited and wonderful. I saw a park bench next to a clump of bushes and sat down. There was a rustle behind me and I got frightened. I thought of men concealing themselves in the bushes. I thought of the sex perverts I read about in Central Park. I wondered if there was someone behind me exposing himself. The idea is repulsive, but exciting too. I think of father now and feel excited. I think of an erect penis. This is connected with my father. There is something about this pushing in my mind. I don’t know what it is, like on the border of my memory. (Pause) |

|

Therapist: |

Mm- |

|

Patient: |

(The patient breathes rapidly and seems to be under great tension.) As a little girl, I slept with my father. I get a funny feeling. I get a funny feeling over my skin, tingly- |

|

(Wolberg, 2005, 1967, p. 662) |

|

BETWEEN THE LINES

In Their Words

“Fortunately, analysis is not the only way to resolve inner conflicts. Life itself still remains a very effective therapist.”

Karen Horney, Our Inner Conflicts, 1945

Therapist InterpretationPsychodynamic therapists listen carefully as patients talk, looking for clues, drawing tentative conclusions, and sharing interpretations when they think the patient is ready to hear them. Interpretations of three phenomena are particularly important—

Patients are showing resistance, an unconscious refusal to participate fully in therapy, when they suddenly cannot free associate or when they change a subject to avoid a painful discussion. They demonstrate transference when they act and feel toward the therapist as they did or do toward important persons in their lives, especially their parents, siblings, and spouses. Consider again the woman who walked in Central Park. As she continues talking, the therapist helps her to explore her transference:

resistance An unconscious refusal to participate fully in therapy.

resistance An unconscious refusal to participate fully in therapy.

transference According to psycho-

transference According to psycho-

|

Patient: |

I get so excited by what is happening here. I feel I’m being held back by needing to be nice. I’d like to blast loose sometimes, but I don’t dare. |

|

Therapist: |

Because you fear my reaction? |

|

Patient: |

The worst thing would be that you wouldn’t like me. You wouldn’t speak to me friendly; you wouldn’t smile; you’d feel you can’t treat me and discharge me from treatment. But I know this isn’t so, I know it. |

|

Therapist: |

Where do you think these attitudes come from? |

|

Patient: |

When I was nine years old, I read a lot about great men in history. I’d quote them and be dramatic. I’d want a sword at my side; I’d dress like an Indian. Mother would scold me. Don’t frown, don’t talk so much. Sit on your hands, over and over again. I did all kinds of things. I was a naughty child. She told me I’d be hurt. Then at fourteen I fell off a horse and broke my back. I had to be in bed. Mother told me on the day I went riding not to, that I’d get hurt because the ground was frozen. I was a stubborn, self- |

|

(Wolberg, 2005, 1967, p. 662) |

|

Why do you think most people try to interpret and make sense of their own dreams? Are such interpretations of value?

Finally, many psychodynamic therapists try to help patients interpret their dreams (Russo, 2014) (see Table 3-2). Freud (1924) called dreams the “royal road to the unconscious.”He believed that repression and other defense mechanisms operate less completely during sleep and that dreams, if correctly interpreted, can reveal unconscious instincts, needs, and wishes. Freud identified two kinds of dream content—

dream A series of ideas and images that form during sleep.

dream A series of ideas and images that form during sleep.

|

|

Men |

Women |

|---|---|---|

|

Being chased or pursued, not injured |

78% |

83% |

|

Sexual experiences |

85 |

73 |

|

Falling |

73 |

74 |

|

School, teachers, studying |

57 |

71 |

|

Arriving too late, e.g., for a train |

55 |

62 |

|

On the verge of falling |

53 |

60 |

|

Trying to do something repeatedly |

55 |

53 |

|

A person living as dead |

43 |

59 |

|

Flying or soaring through the air |

58 |

44 |

|

Sensing a presence vividly |

44 |

50 |

|

Failing an examination |

37 |

48 |

|

Being physically attacked |

40 |

44 |

|

Being frozen with fright |

32 |

44 |

|

A person now dead as living |

37 |

39 |

|

Being a child again |

33 |

38 |

|

Information from: Robert & Zadra, 2014; Copley, 2008; Kantrowitz & Springen, 2004. |

||

CatharsisInsight must be an emotional as well as an intellectual process. Psychodynamic therapists believe that patients must experience catharsis, a reliving of past repressed feelings, if they are to settle internal conflicts and overcome their problems.

catharsis The reliving of past repressed feelings in order to settle internal conflicts and overcome problems.

catharsis The reliving of past repressed feelings in order to settle internal conflicts and overcome problems.

Working ThroughA single episode of interpretation and catharsis will not change the way a person functions. The patient and therapist must examine the same issues over and over in the course of many sessions, each time with greater clarity. This process, called working through, usually takes a long time, often years.

working through The psychoanalytic process of facing conflicts, reinterpreting feelings, and overcoming one’s problems.

working through The psychoanalytic process of facing conflicts, reinterpreting feelings, and overcoming one’s problems.

Current Trends in Psychodynamic TherapyThe past 40 years have witnessed significant changes in the way many psychodynamic therapists conduct sessions. An increased demand for focused, time-

SHORT-

RELATIONAL PSYCHOANALYTIC THERAPYWhereas Freud believed that psychodynamic therapists should take on the role of a neutral, distant expert during a treatment session, a contemporary school of psychodynamic therapy referred to as relational psychoanalytic therapy argues that therapists are key figures in the lives of patients—

relational psychoanalytic therapy A form of psychodynamic therapy that believes the reactions and beliefs of therapists should be openly included in the therapy process.

relational psychoanalytic therapy A form of psychodynamic therapy that believes the reactions and beliefs of therapists should be openly included in the therapy process.

Assessing the Psychodynamic Model

Freud and his followers have helped change the way abnormal functioning is understood. Largely because of their work, a wide range of theorists today look for answers outside of biological processes. Psychodynamic theorists have also helped us to understand that abnormal functioning may be rooted in the same processes as normal functioning (see PsychWatch below). Psychological conflict is a common experience; it leads to abnormal functioning only if the conflict becomes excessive.

Freud and his many followers have also had a monumental impact on treatment. They were the first to apply theory systematically to treatment. They were also the first to demonstrate the potential of psychological, as opposed to biological, treatment, and their ideas have served as starting points for many other psychological treatments.

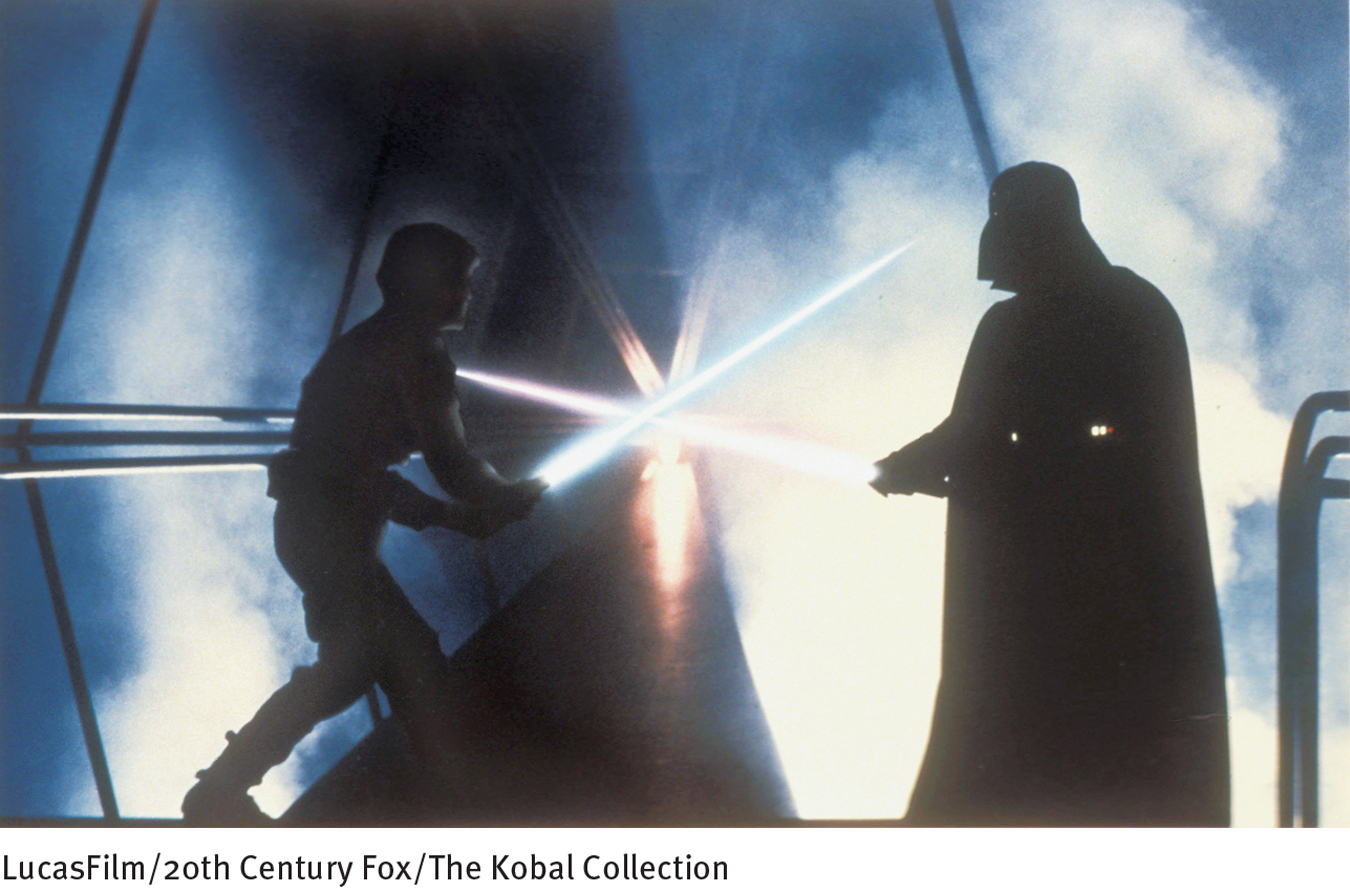

What are some of the ways that Freud’s theories have affected literature, film and television, philosophy, child rearing, and education in Western society?

At the same time, the psychodynamic model has its shortcomings. Its concepts are hard to research (Prochaska & Norcross, 2013; Levy et al., 2012). Because processes such as id drives, ego defenses, and fixation are abstract and supposedly operate at an unconscious level, there is no way of knowing for certain if they are occurring. Not surprisingly, then, psychodynamic explanations and treatments have received limited research support over the years, and psychodynamic theorists rely largely on evidence provided by individual case studies. Nevertheless, recent research evidence suggests that long-

PsychWatch

Maternal Instincts

On an August day in 1996, a 3-

When Binti was herself an infant, she had been removed from her mother, Lulu, who did not have enough milk. To make up for this loss, keepers at the zoo worked around the clock to nurture Binti; she was always being held in someone’s arms. When Binti became pregnant at age 6, trainers were afraid that the early separation from her mother would leave her ill prepared to raise an infant of her own. So they gave her mothering lessons and taught her to nurse and carry around a stuffed doll.

After the incident at the zoo, clinical theorists had a field day interpreting the gorilla’s gentle and nurturing care for the child, each within his or her preferred theory. Many evolutionary theorists, for example, viewed the behavior as an expression of the maternal instincts that have helped the gorilla species to survive and evolve. Some psychodynamic theorists suggested that the gorilla was expressing feelings of attachment and bonding, which she had already felt with her own 17-