3.3 The Behavioral Model

Like psychodynamic theorists, behavioral theorists believe that our actions are determined largely by our experiences in life. However, the behavioral model concentrates on behaviors, the responses an organism makes to its environment. Behaviors can be external (going to work, say) or internal (having a feeling or thought). In turn, behavioral theorists base their explanations and treatments on principles of learning, the processes by which these behaviors change in response to the environment.

Many learned behaviors help people to cope with daily challenges and to lead happy, productive lives. However, abnormal behaviors also can be learned. Behaviorists who try to explain Philip Berman’s problems might view him as a man who has received improper training: He has learned behaviors that offend others and repeatedly work against him.

Whereas the psychodynamic model had its beginnings in the clinical work of physicians, the behavioral model began in laboratories where psychologists were running experiments on conditioning, simple forms of learning. The researchers manipulated stimuli and rewards, then observed how their manipulations affected the responses of their research participants.

conditioning A simple form of learning.

conditioning A simple form of learning.

During the 1950s, many clinicians became frustrated with what they viewed as the vagueness and slowness of the psychodynamic model. Some of them began to apply the principles of learning to the study and treatment of psychological problems. Their efforts gave rise to the behavioral model of abnormality.

How Do Behaviorists Explain Abnormal Functioning?

Learning theorists have identified several forms of conditioning, and each may produce abnormal behavior as well as normal behavior. In operant conditioning, for example, humans and animals learn to behave in certain ways as a result of receiving rewards—consequences of one kind or another—

operant conditioning A process of learning in which behavior that leads to satisfying consequences is likely to be repeated.

operant conditioning A process of learning in which behavior that leads to satisfying consequences is likely to be repeated.

modeling A process of learning in which an individual acquires responses by observing and imitating others.

modeling A process of learning in which an individual acquires responses by observing and imitating others.

Working for Pavlov

In Ivan Pavlov’s experimental device, the dog’s saliva was collected in a tube as it was secreted, and the amount was recorded on a revolving cylinder. The experimenter observed the dog through a one-

In a third form of conditioning, classical conditioning, learning occurs by temporal association. When two events repeatedly occur close together in time, they become fused in a person’s mind, and before long the person responds in the same way to both events. If one event produces a response of joy, the other brings joy as well; if one event brings feelings of relief, so does the other. A closer look at this form of conditioning illustrates how the behavioral model can account for abnormal functioning.

classical conditioning A process of learning by temporal association in which two events that repeatedly occur close together in time become fused in a person’s mind and produce the same response.

classical conditioning A process of learning by temporal association in which two events that repeatedly occur close together in time become fused in a person’s mind and produce the same response.

Ivan Pavlov (1849–

In the vocabulary of classical conditioning, the meat in this demonstration is an unconditioned stimulus (US). It elicits the unconditioned response (UR) of salivation, that is, a natural response with which the dog is born. The sound of the bell is a conditioned stimulus (CS), a previously neutral stimulus that comes to be linked with meat in the dog’s mind. As such, it too produces a salivation response. When the salivation response is produced by the conditioned stimulus rather than by the unconditioned stimulus, it is called a conditioned response (CR).

|

Before Conditioning |

After Conditioning |

|---|---|

|

CS: Tone → No response |

CS: Tone → CR: Salivation |

|

US: Meat → UR: Salivation |

US: Meat → UR: Salivation |

Classical conditioning explains many familiar behaviors. The romantic feelings a young man experiences when he smells his girlfriend’s perfume, say, may represent a conditioned response. Initially, this perfume may have had little emotional effect on him, but because the fragrance was present during several romantic encounters, it came to elicit a romantic response.

Abnormal behaviors, too, can be acquired by classical conditioning. Consider a young boy who is repeatedly frightened by a neighbor’s large German shepherd dog. Whenever the child walks past the neighbor’s front yard, the dog barks loudly and lunges at him, stopped only by a rope tied to the porch. In this unfortunate situation, the boy’s parents are not surprised to discover that he develops a fear of dogs. They are stumped, however, by another intense fear the child displays, a fear of sand. They cannot understand why he cries whenever they take him to the beach and screams in fear if sand even touches his skin.

Where did this fear of sand come from? Classical conditioning. It turns out that a big sandbox is set up in the neighbor’s front yard for the dog to play in. Every time the dog barks and lunges at the boy, the sandbox is there too. After repeated pairings of this kind, the child comes to fear sand as much as he fears the dog.

Behavioral Therapies

Behavioral therapists aim to identify the behaviors that are causing a person’s problems and then try to replace them with more appropriate ones by applying the principles of classical conditioning, operant conditioning, or modeling (Antony, 2014). The therapist’s attitude toward the client is that of teacher rather than healer.

Classical conditioning treatments, for example, may be used to change abnormal reactions to particular stimuli. Systematic desensitization is one such method, often applied in cases of phobia—a specific and unreasonable fear. In this step-

systematic desensitization A behavioral treatment in which clients with phobias learn to react calmly instead of with intense fear to the objects or situations they dread.

systematic desensitization A behavioral treatment in which clients with phobias learn to react calmly instead of with intense fear to the objects or situations they dread.

Read the word “dog” in a book.

Hear a neighbor’s barking dog.

See photos of small dogs.

Page 71See photos of large dogs.

See a movie in which a dog is prominently featured.

Be in the same room with a quiet, small dog.

Pet a small, cuddly dog.

Be in the same room with a large dog.

Pet a big, frisky dog.

Play roughhouse with a dog.

Desensitization therapists next have their clients either imagine or actually confront each item on the hierarchy while in a state of relaxation. In step-

Assessing the Behavioral Model

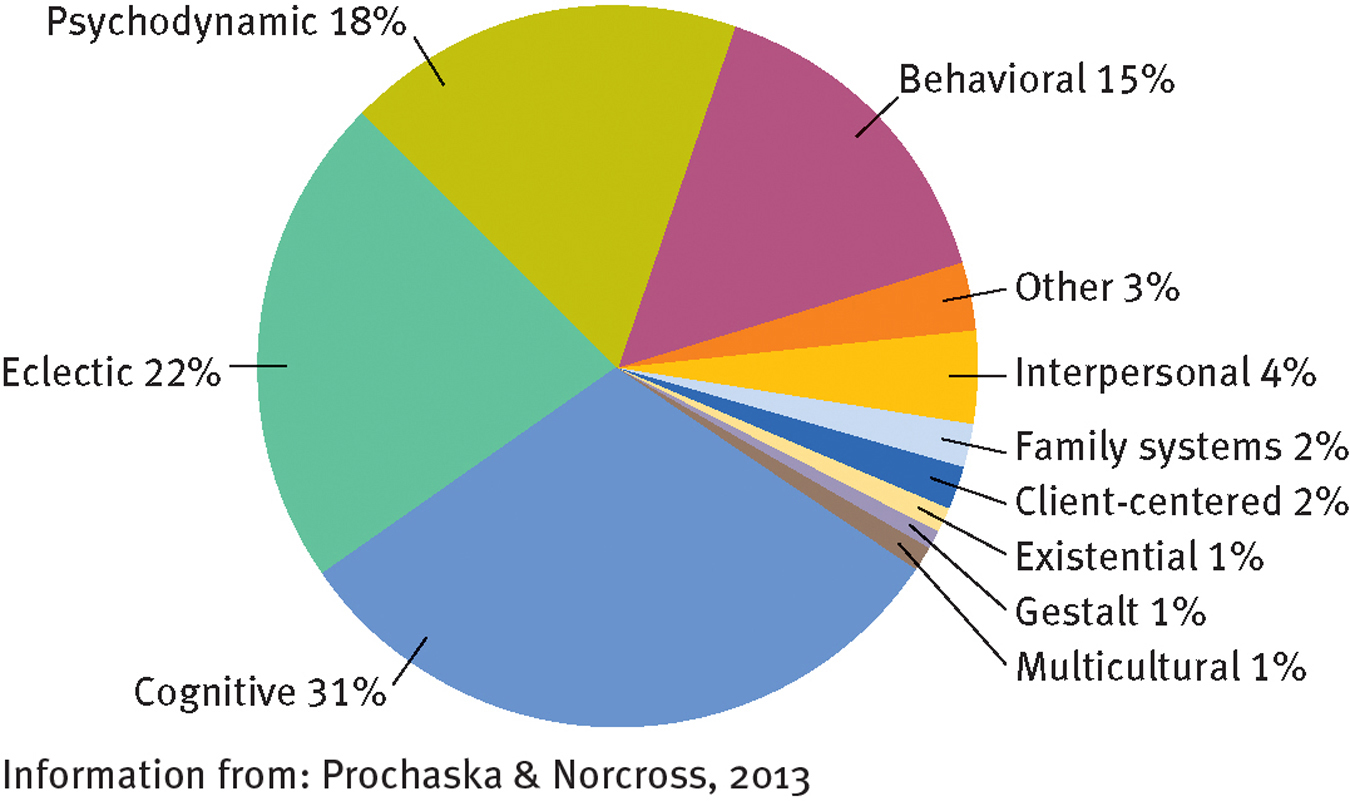

The behavioral model has become a powerful force in the clinical field. Various behavioral theories have been proposed over the years, and many treatment techniques have been developed. As you can see in Figure 3-4 below, approximately 15 percent of today’s clinical psychologists report that their approach is mainly behavioral (Prochaska & Norcross, 2013).

Theoretical orientations of today’s clinical psychologists

In one survey, 22 percent of clinical psychologists labeled their approach as “eclectic,” 31 percent considered their model “cognitive,” and 18 percent called their orientation “psychodynamic”.

Perhaps the greatest appeal of the behavioral model is that it can be tested in the laboratory, whereas psychodynamic theories generally cannot. The behaviorists’ basic concepts—

At the same time, research has also revealed weaknesses in the model. Certainly behavioral researchers have produced specific symptoms in participants. But are these symptoms ordinarily acquired in this way? There is still no indisputable evidence that most people with psychological disorders are victims of improper conditioning. Similarly, behavioral therapies have limitations. The improvements noted in the therapist’s office do not always extend to real life. Nor do they necessarily last without continued therapy.

Finally, some critics hold that the behavioral view is too simplistic, that its concepts fail to account for the complexity of behavior. In 1977 Albert Bandura, a leading behaviorist, argued that in order to feel happy and function effectively people must develop a positive sense of self-efficacy. That is, they must know that they can master and perform needed behaviors whenever necessary. Other behaviorists of the 1960s and 1970s similarly recognized that human beings engage in cognitive behaviors, such as anticipating or interpreting—

self-efficacy The belief that one can master and perform needed behaviors whenever necessary.

self-efficacy The belief that one can master and perform needed behaviors whenever necessary.

cognitive-behavioral therapies Therapy approaches that seek to help clients change both counterproductive behaviors and dysfunctional ways of thinking.

cognitive-behavioral therapies Therapy approaches that seek to help clients change both counterproductive behaviors and dysfunctional ways of thinking.