3.4 The Cognitive Model

Philip Berman, like the rest of us, has cognitive abilities—

In the early 1960s two clinicians, Albert Ellis (1962) and Aaron Beck (1967), proposed that cognitive processes are at the center of behaviors, thoughts, and emotions and that we can best understand abnormal functioning by looking to cognition—

How Do Cognitive Theorists Explain Abnormal Functioning?

According to cognitive theorists, abnormal functioning can result from several kinds of cognitive problems. Some people may make assumptions and adopt attitudes that are disturbing and inaccurate (Beck & Weishaar, 2014; Ellis, 2014). Philip Berman, for example, often seems to assume that his past history has locked him in his present situation. He believes that he was victimized by his parents and that he is now forever doomed by his past. He seems to approach all new experiences and relationships with expectations of failure and disaster.

BETWEEN THE LINES

In Their Words

“I am so clever that sometimes I don’t understand a single word of what I am saying.”

Oscar Wilde, The Happy Prince and Other Stories

Illogical thinking processes are another source of abnormal functioning, according to cognitive theorists. Beck, for example, has found that some people consistently think in illogical ways and keep arriving at self-

Cognitive Therapies

According to cognitive therapists, people with psychological disorders can overcome their problems by developing new, more functional ways of thinking. Because different forms of abnormality may involve different kinds of cognitive dysfunctioning, cognitive therapists have developed a number of strategies. Beck, for example, has developed an approach that is widely used, particularly in cases of depression (Beck & Weishaar, 2014).

In Beck’s approach, called simply cognitive therapy, therapists help clients recognize the negative thoughts, biased interpretations, and errors in logic that dominate their thinking and, according to Beck, cause them to feel depressed. Therapists also guide clients to challenge their dysfunctional thoughts, try out new interpretations, and ultimately apply the new ways of thinking in their daily lives. As you will see in Chapter 8, people with depression who are treated with Beck’s approach improve much more than those who receive no treatment.

cognitive therapy A therapy developed by Aaron Beck that helps people recognize and change their faulty thinking processes.

cognitive therapy A therapy developed by Aaron Beck that helps people recognize and change their faulty thinking processes.

How might your efforts to reason with a depressed friend differ from Beck’s cognitive therapy strategies for people with depression?

In the excerpt that follows, a cognitive therapist guides a depressed 26-

|

Therapist: |

How do you understand it? |

|

Patient: |

I get depressed when things go wrong. Like when I fail a test. |

|

Therapist: |

How can failing a test make you depressed? |

|

Patient: |

Well, if I fail I’ll never get into law school. |

|

Therapist: |

So failing the test means a lot to you. But if failing a test could drive people into clinical depression, wouldn’t you expect everyone who failed the test to have a depression? … Did everyone who failed get depressed enough to require treatment? |

|

Patient: |

No, but it depends on how important the test was to the person. |

|

Therapist: |

Right, and who decides the importance? |

|

Patient: |

I do. |

|

Therapist: |

And so, what we have to examine is your way of viewing the test (or the way that you think about the test) and how it affects your chances of getting into law school. Do you agree? |

|

Patient: |

Right…. |

|

Therapist: |

Now what did failing mean? |

|

Patient: |

(Tearful) That I couldn’t get into law school. |

|

Therapist: |

And what does that mean to you? |

|

Patient: |

That I’m just not smart enough. |

|

Therapist: |

Anything else? |

|

Patient: |

That I can never be happy. |

|

Therapist: |

And how do these thoughts make you feel? |

|

Patient: |

Very unhappy. |

|

Therapist: |

So it is the meaning of failing a test that makes you very unhappy. In fact, believing that you can never be happy is a powerful factor in producing unhappiness. So, you get yourself into a trap— |

|

(Beck et al., 1979, pp. 145– |

|

Assessing the Cognitive Model

The cognitive model has had very broad appeal. In addition to a large number of cognitive-

BETWEEN THE LINES

In Their Words

“The greatest discovery of my generation is that human beings can alter their lives by altering their attitudes of mind.”

William James (1842–

The cognitive model is popular for several reasons. First, it focuses on a process unique to human beings—

Cognitive theories also lend themselves to research. Investigators have found that people with psychological disorders often make the kinds of assumptions and errors in thinking the theorists claim (Ingram et al., 2007). Yet another reason for the popularity of this model is the impressive performance of cognitive and cognitive-

Nevertheless, the cognitive model, too, has its drawbacks. First, although disturbed cognitive processes are found in many forms of abnormality, their precise role has yet to be determined. The cognitions seen in psychologically troubled people could well be a result rather than a cause of their difficulties. Second, although cognitive and cognitive-

In response to such limitations, a new group of cognitive and cognitive-

As you will see in Chapter 5, ACT and other new-

A final drawback of the cognitive model is that, like the other models you have read about, it is narrow in certain ways. Although cognition is a very special human dimension, it is still only one part of human functioning. Aren’t human beings more than the sum of their thoughts, emotions, and behaviors? Shouldn’t explanations of human functioning also consider broader issues, such as how people approach life, what value they extract from it, and how they deal with the question of life’s meaning? This is the position of the humanistic-

PsychWatch

Cybertherapy: Surfing for Help

As you read in Chapter 1, computer-

The clinical field’s first journey into the digital world took the form of computer software therapy programs (Harklute, 2010; Tantam, 2006). These programs, which continue to be popular, are designed to reduce emotional distress through typed conversations between human “clients” and their computers. The software programmers try to apply the basic principles of actual therapy. One program, for example, helps people state their problems in “if-

Advocates of software therapy programs argue that many people find it easier to disclose sensitive personal information to a computer than to a therapist, and indeed research indicates that some of the programs are helpful to a degree (Emmelkamp, 2011; Harklute, 2010). Computer experts currently are working to develop software programs for recognizing clients’ faces and emotions. This development will likely increase the versatility and appeal of software therapy programs.

Another form of cybertherapy, e-

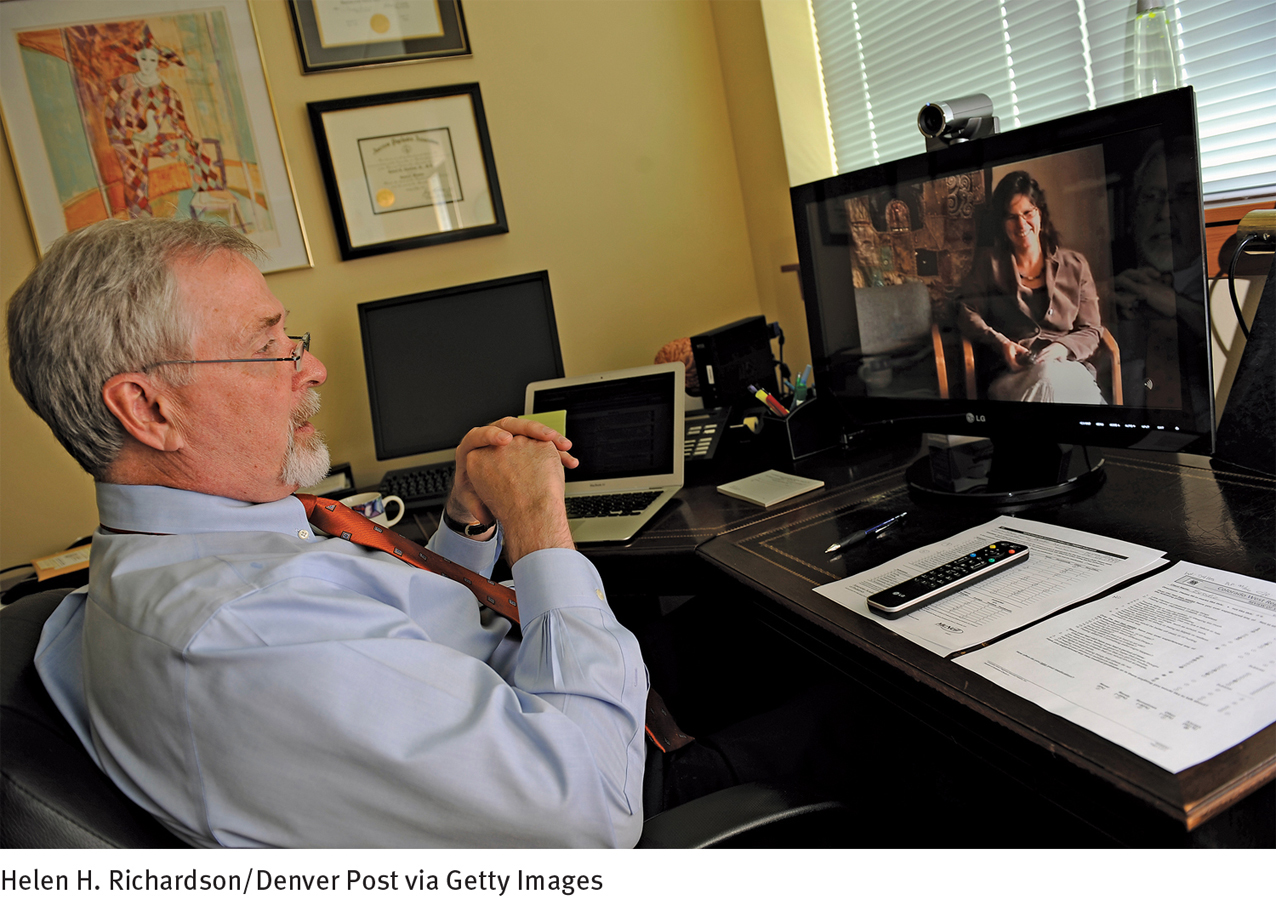

Also on the rise is visual e-

Still more common than either e-

Cybertherapy is still being developed and researched, and its actual effectiveness has yet to be determined. At the same time, the rapid growth of this approach serves as a reminder that digital technology’s impact on the mental health field is as powerful and potentially useful as its impact on most other fields in our society.