5.5 Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder

BETWEEN THE LINES

An Obsession That Changed the World

The experiments that led Louis Pasteur to the pasteurization process may have been driven in part by his obsession with contamination and infection. Apparently he would not shake hands and regularly wiped his glass and plate before dining (Asimov, 1997).

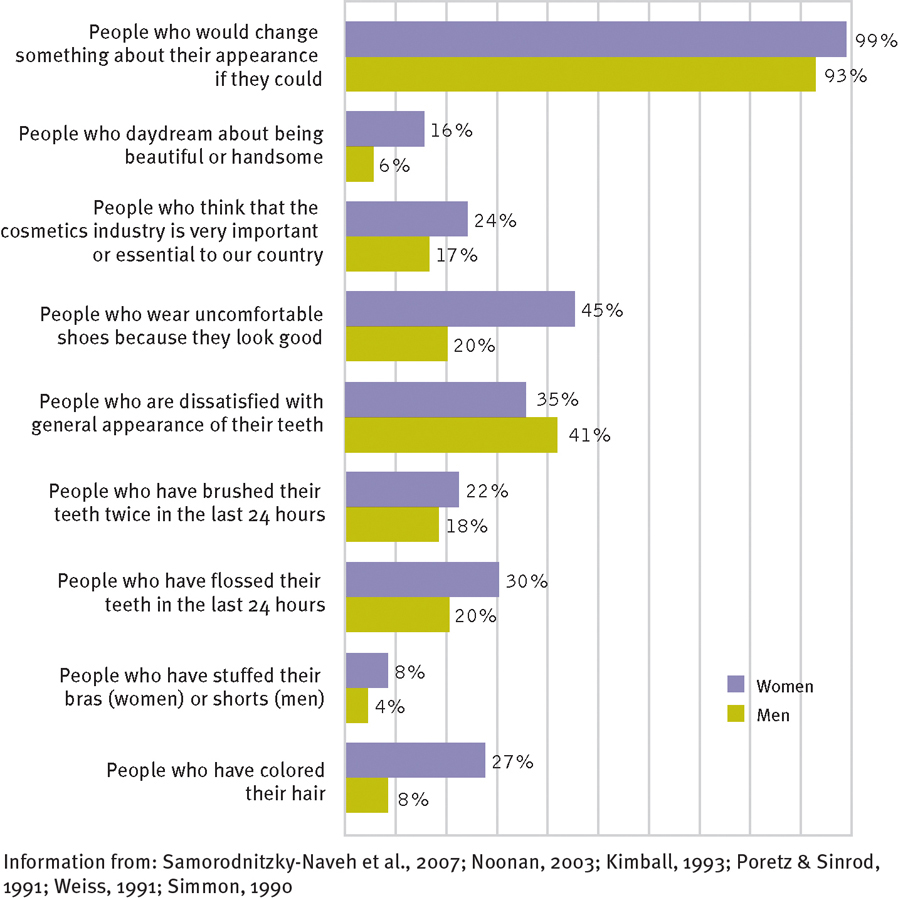

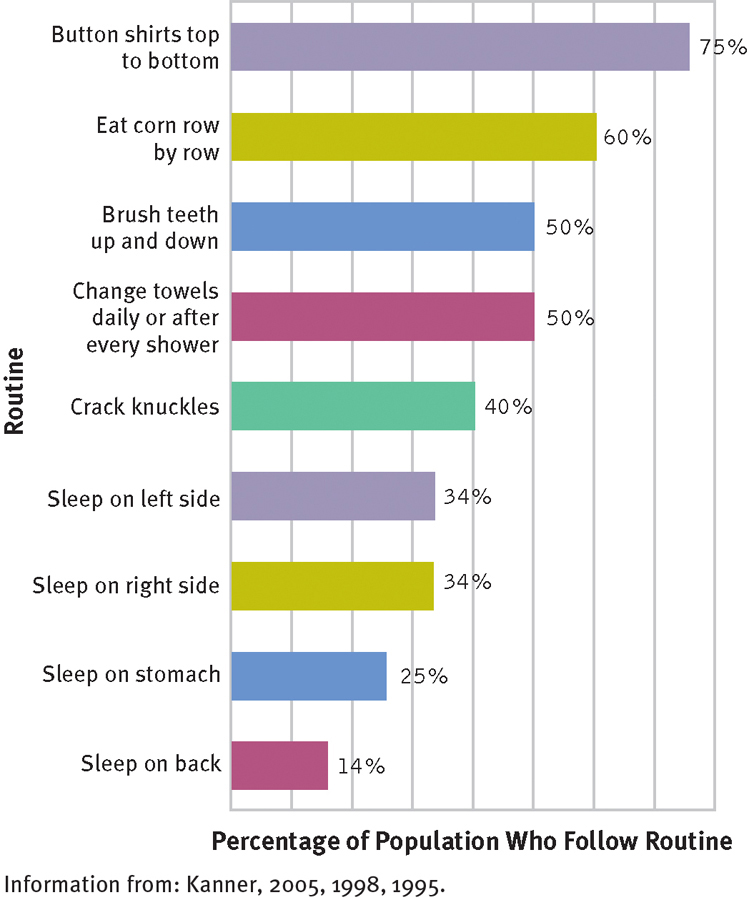

Obsessions are persistent thoughts, ideas, impulses, or images that seem to invade a person’s consciousness. Compulsions are repetitive and rigid behaviors or mental acts that people feel they must perform in order to prevent or reduce anxiety. As Figure 5-6 indicates, minor obsessions and compulsions are familiar to almost everyone. You may find yourself filled with thoughts about an upcoming performance or exam or keep wondering whether you forgot to turn off the stove or lock the door. You may feel better when you avoid stepping on cracks, turn away from black cats, or arrange your closet in a particular manner.

obsession A persistent thought, idea, impulse, or image that is experienced repeatedly, feels intrusive, and causes anxiety.

obsession A persistent thought, idea, impulse, or image that is experienced repeatedly, feels intrusive, and causes anxiety.

compulsion A repetitive and rigid behavior or mental act that a person feels driven to perform in order to prevent or reduce anxiety.

compulsion A repetitive and rigid behavior or mental act that a person feels driven to perform in order to prevent or reduce anxiety.

Figure 5.6: figure 5-6

Normal routines

Most people find it comforting to follow set routines when they carry out everyday activities, and, in fact, 40 percent become irritated if they must depart from their routines.

Page 162

Minor obsessions and compulsions can play a helpful role in life. Little rituals often calm us during times of stress. A person who repeatedly hums a tune or taps his or her fingers during a test may be releasing tension and thus improving performance. Many people find it comforting to repeat religious or cultural rituals, such as touching a mezuzah, sprinkling holy water, or fingering rosary beads.

According to DSM-5, a diagnosis of obsessive-compulsive disorder is called for when obsessions or compulsions feel excessive or unreasonable, cause great distress, take up much time, and interfere with daily functions (see Table 5-10). Although obsessive-compulsive disorder is not classified as an anxiety disorder in DSM-5, anxiety does play a major role in this pattern. The obsessions cause intense anxiety, while the compulsions are aimed at preventing or reducing anxiety. In addition, anxiety rises if a person tries to resist his or her obsessions or compulsions.

obsessive-compulsive disorder A disorder in which a person has recurrent and unwanted thoughts, a need to perform repetitive and rigid actions, or both.

obsessive-compulsive disorder A disorder in which a person has recurrent and unwanted thoughts, a need to perform repetitive and rigid actions, or both.

Table 5.10: table: 5-10Dx Checklist

Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder |

|

|

Occurrence of repeated obsessions, compulsions, or both. |

|

|

The obsessions or compulsions take up considerable time. |

|

|

Significant distress or impairment. |

Information from: APA, 2013. |

An individual with this disorder observed: “I can’t get to sleep unless I am sure everything in the house is in its proper place so that when I get up in the morning, the house is organized. I work like mad to set everything straight before I go to bed, but, when I get up in the morning, I can think of a thousand things that I ought to do…. I can’t stand to know something needs doing and I haven’t done it” (McNeil, 1967, pp. 26–28). Research indicates that several additional disorders are closely related to obsessive-compulsive disorder in their features, causes, and treatment responsiveness, and so, as you will soon see, DSM-5 has grouped them together with obsessive-compulsive disorder.

Between 1 and 2 percent of the people in the United States and other countries throughout the world suffer from obsessive-compulsive disorder in any given year (Kessler et al., 2012; Björgvinsson & Hart, 2008; Wetherell et al., 2006). As many as 3 percent develop the disorder at some point during their lives. It is equally common in men and women and among people of different races and ethnic groups (Matsunaga & Seedat, 2011). The disorder usually begins by young adulthood and typically persists for many years, although its symptoms and their severity may fluctuate over time (Angst et al., 2004). It is estimated that more than 40 percent of people with obsessive-compulsive disorder may seek treatment, many for an extended period (Patel et al., 2014; Kessler et al., 1999, 1994).

What Are the Features of Obsessions and Compulsions?

Obsessive thoughts feel both intrusive and foreign to the people who experience them. Attempts to ignore or resist these thoughts may arouse even more anxiety, and before long they come back more strongly than ever. People with obsessions typically are quite aware that their thoughts are excessive.

Obsessions often take the form of obsessive wishes (for example, repeated wishes that one’s spouse would die), impulses (repeated urges to yell out obscenities at work or in church), images (fleeting visions of forbidden sexual scenes), ideas (notions that germs are lurking everywhere), or doubts (concerns that one has made or will make a wrong decision). In the following excerpt, a clinician describes a 20-year-old college junior who was plagued by obsessive doubts.

Page 163

He now spent hours each night “rehashing” the day’s events, especially interactions with friends and teachers, endlessly making “right” in his mind any and all regrets. He likened the process to playing a videotape of each event over and over again in his mind, asking himself if he had behaved properly and telling himself that he had done his best, or had said the right thing every step of the way. He would do this while sitting at his desk, supposedly studying; and it was not unusual for him to look at the clock after such a period of rumination and note that, to his surprise, two or three hours had elapsed.

(Spitzer et al., 1981, pp. 20–21)

Certain basic themes run through the thoughts of most people troubled by obsessive thinking (Bokor & Anderson, 2014; Abramowitz, McKay, & Taylor, 2008). The most common theme appears to be dirt or contamination (Torres et al., 2013; Tolin & Meunier, 2008). Other common ones are violence and aggression, orderliness, religion, and sexuality. The prevalence of such themes may vary from culture to culture (Matsunaga & Seedat, 2011). Religious obsessions, for example, seem to be more common in cultures or countries with strict moral codes and religious values (Björgvinsson & Hart, 2008).

Compulsions are similar to obsessions in many ways. For example, although compulsive behaviors are technically under voluntary control, the people who feel they must do them have little sense of choice in the matter. Most of these individuals recognize that their behavior is unreasonable, but they believe at the same time something terrible will happen if they don’t perform the compulsions. After performing a compulsive act, they usually feel less anxious for a short while. For some people the compulsive acts develop into detailed rituals. They must go through the ritual in exactly the same way every time, according to certain rules.

Cultural rituals Rituals do not necessarily reflect compulsions. Indeed, cultural and religious rituals often give meaning and comfort to their practitioners. Here Buddhist monks splash water over themselves during their annual winter prayers at a temple in Tokyo. This cleansing ritual is performed to pray for good luck.

Like obsessions, compulsions take various forms. Cleaning compulsions are very common. People with these compulsions feel compelled to keep cleaning themselves, their clothing, or their homes. The cleaning may follow ritualistic rules and be repeated dozens or hundreds of times a day. People with checking compulsions check the same items over and over—door locks, gas taps, important papers—to make sure that all is as it should be (Coleman et al., 2011). Another common compulsion is the constant effort to seek order or balance (Coles & Pietrefesa, 2008). People with this compulsion keep placing certain items (clothing, books, foods) in perfect order in accordance with strict rules. Touching, verbal, and counting compulsions are also common.

Although some people with obsessive-compulsive disorder experience obsessions only or compulsions only, most experience both (Clark & Guyitt, 2008). In fact, compulsive acts are often a response to obsessive thoughts. One study found that in most cases, compulsions seemed to represent a yielding to obsessive doubts, ideas, or urges (Akhtar et al., 1975). A woman who keeps doubting that her house is secure may yield to that obsessive doubt by repeatedly checking locks and gas jets. Or a man who obsessively fears contamination may yield to that fear by performing cleaning rituals. The study also found that compulsions sometimes serve to help control obsessions. A teenager describes how she tried to control her obsessive fears of contamination by performing counting and verbal rituals:

Page 164

|

|

If I heard the word, like, something that had to do with germs or disease, it would be considered something bad, and so I had things that would go through my mind that were sort of like “cross that out and it’ll make it okay” to hear that word. |

|

|

|

|

|

Like numbers or words that seemed to be sort of like a protector. |

|

|

What numbers and what words were they? |

|

|

It started out to be the number 3 and multiples of 3 and then words like “soap and water,” something like that; and then the multiples of 3 got really high, and they’d end up to be 124 or something like that. It got real bad then. |

(Spitzer et al., 1981, p. 137) |

Many people with obsessive-compulsive disorder worry that they will act out their obsessions. A man with obsessive images of wounded loved ones may worry that he is but a step away from committing murder, or a woman with obsessive urges to yell out in church may worry that she will one day give in to them and embarrass herself. Most such concerns are unfounded. Although many obsessions lead to compulsive acts—particularly to cleaning and checking compulsions—they usually do not lead to violence or immoral conduct.

Obsessive-compulsive disorder was once among the least understood of the psychological disorders. In recent decades, however, researchers have begun to learn more about it. The most influential explanations and treatments come from the psychodynamic, behavioral, cognitive, and biological models.

The Psychodynamic Perspective

As you have seen, psychodynamic theorists believe that an anxiety disorder develops when children come to fear their own id impulses and use ego defense mechanisms to lessen the resulting anxiety. What distinguishes obsessive-compulsive disorder from other anxiety disorders, in their view, is that here the battle between anxiety-provoking id impulses and anxiety-reducing defense mechanisms is not buried in the unconscious but is played out in overt thoughts and actions. The id impulses usually take the form of obsessive thoughts, and the ego defenses appear as counterthoughts or compulsive actions. A woman who keeps imagining her mother lying broken and bleeding, for example, may counter those thoughts with repeated safety checks throughout the house.

According to psychodynamic theorists, three ego defense mechanisms are particularly common in obsessive-compulsive disorder: isolation, undoing, and reaction formation. People who resort to isolation simply disown their unwanted thoughts and experience them as foreign intrusions. People who engage in undoing perform acts that are meant to cancel out their undesirable impulses. Those who wash their hands repeatedly, for example, may be symbolically undoing their unacceptable id impulses. People who develop a reaction formation take on a lifestyle that directly opposes their unacceptable impulses. A person may live a life of compulsive kindness and devotion to others in order to counter unacceptable aggressive impulses.

isolation An ego defense mechanism in which people unconsciously isolate and disown undesirable and unwanted thoughts, experiencing them as foreign intrusions.

isolation An ego defense mechanism in which people unconsciously isolate and disown undesirable and unwanted thoughts, experiencing them as foreign intrusions.

undoing An ego defense mechanism whereby a person unconsciously cancels out an unacceptable desire or act by performing another act.

undoing An ego defense mechanism whereby a person unconsciously cancels out an unacceptable desire or act by performing another act.

reaction formation An ego defense mechanism whereby a person suppresses an unacceptable desire by taking on a lifestyle that expresses the opposite desire.

reaction formation An ego defense mechanism whereby a person suppresses an unacceptable desire by taking on a lifestyle that expresses the opposite desire.

Page 165

Sigmund Freud traced obsessive-compulsive disorder to the anal stage of development (occurring at about 2 years of age). He proposed that during this stage some children experience intense rage and shame as a result of negative toilet-training experiences. Other psychodynamic theorists have argued instead that such early rage reactions are rooted in feelings of insecurity (Erikson, 1963; Sullivan, 1953; Horney, 1937). Either way, these children repeatedly feel the need to express their strong aggressive id impulses while at the same time knowing they should try to restrain and control the impulses. If this conflict between the id and ego continues, it may eventually blossom into obsessive-compulsive disorder. Overall, research has not clearly supported the psychodynamic explanation (Busch et al., 2010; Fitz, 1990).

When treating patients with obsessive-compulsive disorder, psychodynamic therapists try to help the individuals uncover and overcome their underlying conflicts and defenses, using the customary techniques of free association and therapist interpretation. Research has offered little evidence, however, that a traditional psychodynamic approach is of much help (Bram & Björgvinsson, 2004). Thus some psychodynamic therapists now prefer to treat these patients with short-term psychodynamic therapies, which, as you saw in Chapter 3, are more direct and action-oriented than the classical techniques.

The Behavioral Perspective

Behaviorists have concentrated on explaining and treating compulsions rather than obsessions. They propose that people happen upon their compulsions quite randomly. In a fearful situation, they happen just coincidentally to wash their hands, say, or dress a certain way. When the threat lifts, they link the improvement to that particular action. After repeated accidental associations, they believe that the action is bringing them good luck or actually changing the situation, and so they perform the same actions again and again in similar situations. The act becomes a key method of avoiding or reducing anxiety (Grayson, 2014; Frost & Steketee, 2001).

Getting down and dirty In one exposure and response prevention assignment, clients with cleaning compulsions might be instructed to do heavy-duty gardening and then resist washing their hands or taking a shower. They may never go so far as to participate in and enjoy mud wrestling, like these delightfully filthy individuals at the annual Mud Day event in Westland, Michigan, but you get the point.

The famous clinical scientist Stanley Rachman and his associates have shown that compulsions do appear to be rewarded by a reduction in anxiety. In one of their experiments, for example, 12 research participants with compulsive hand-washing rituals were placed in contact with objects that they considered contaminated (Hodgson & Rachman, 1972). As behaviorists would predict, the hand-washing rituals of these participants seemed to lower their anxiety.

If people keep performing compulsive behaviors in order to prevent bad outcomes and ensure positive outcomes, can’t they be taught that such behaviors are not really serving this purpose? In a behavioral treatment called exposure and response prevention (or exposure and ritual prevention), first developed by psychiatrist Victor Meyer (1966), clients are repeatedly exposed to objects or situations that produce anxiety, obsessive fears, and compulsive behaviors, but they are told to resist performing the behaviors they feel so bound to perform. Because people find it very difficult to resist such behaviors, therapists may set an example first.

exposure and response prevention A behavioral treatment for obsessive-compulsive disorder that exposes a client to anxiety-arousing thoughts or situations and then prevents the client from performing his or her compulsive acts. Also called exposure and ritual prevention.

exposure and response prevention A behavioral treatment for obsessive-compulsive disorder that exposes a client to anxiety-arousing thoughts or situations and then prevents the client from performing his or her compulsive acts. Also called exposure and ritual prevention.

Have you ever tried an informal version of exposure and response prevention in order to stop behaving in certain ways?

Many behavioral therapists now use exposure and response prevention in both individual and group therapy formats. Some of them also have people carry out self-help procedures at home (Franklin & Foa, 2014; Abramowitz et al., 2011; Simpson et al., 2011). That is, they assign homework in exposure and response prevention, such as these assignments given to a woman with a cleaning compulsion:

Page 166

Do not mop the floor of your bathroom for a week. After this, clean it within three minutes, using an ordinary mop. Use this mop for other chores as well without cleaning it.

Buy a fluffy mohair sweater and wear it for a week. When taking it off at night do not remove the bits of fluff. Do not clean your house for a week.

You, your husband, and children all have to keep shoes on. Do not clean the house for a week.

Drop a cookie on the contaminated floor, pick the cookie up and eat it.

Leave the sheets and blankets on the floor and then put them on the beds. Do not change these for a week.

(Emmelkamp, 1982, pp. 299–300)

BETWEEN THE LINES

People who try to avoid all contamination and rid themselves and their world of all germs are fighting a losing battle. While talking, the average person sprays 300 microscopic saliva droplets per minute, or 2.5 per word.

Eventually this woman was able to set up a reasonable routine for cleaning herself and her home.

Between 55 and 85 percent of clients with obsessive-compulsive disorder have been found to improve considerably with exposure and response prevention, improvements that often continue indefinitely (Abramowitz et al., 2011, 2008; McKay, Taylor, & Abramowitz, 2010). The effectiveness of this approach suggests that people with this disorder are like the superstitious man in the old joke who keeps snapping his fingers to keep elephants away. When someone points out, “But there aren’t any elephants around here,” the man replies, “See? It works!” One review concludes, “With hindsight, it is possible to see that the [obsessive-compulsive] individual has been snapping his fingers, and unless he stops (response prevention) and takes a look around at the same time (exposure), he isn’t going to learn much of value about elephants” (Berk & Efran, 1983, p. 546).

At the same time, research has revealed key limitations in exposure and response prevention. Few clients who receive the treatment overcome all their symptoms, and as many as one-quarter fail to improve at all (Franklin & Foa, 2014; Frost & Steketee, 2001). Also, the approach is of limited help to those who have obsessions but no compulsions (Hohagen et al., 1998).

The Cognitive Perspective

Cognitive theorists begin their explanation of obsessive-compulsive disorder by pointing out that everyone has repetitive, unwanted, and intrusive thoughts. Anyone might have thoughts of harming others or being contaminated by germs, for example, but most people dismiss or ignore them with ease. Those who develop this disorder, however, typically blame themselves for such thoughts and expect that somehow terrible things will happen (Grayson, 2014; Shafran, 2005; Salkovskis, 1999, 1985). To avoid such negative outcomes, they try to neutralize the thoughts—thinking or behaving in ways meant to put matters right or to make amends (Jacob, Larson, & Storch, 2014; Salkovskis et al., 2003).

neutralizing A person’s attempt to eliminate unwanted thoughts by thinking or behaving in ways that put matters right internally, making up for the unacceptable thoughts.

neutralizing A person’s attempt to eliminate unwanted thoughts by thinking or behaving in ways that put matters right internally, making up for the unacceptable thoughts.

BETWEEN THE LINES

Your mind wanders almost one-half of the time on average (Killingsworth & Gilbert, 2010).

Neutralizing acts might include requesting special reassurance from others, deliberately thinking “good” thoughts, washing one’s hands, or checking for possible sources of danger. When a neutralizing effort brings about a temporary reduction in discomfort, it is reinforced and will likely be repeated. Eventually the neutralizing thought or act is used so often that it becomes, by definition, an obsession or compulsion. At the same time, the individual becomes more and more convinced that his or her unpleasant intrusive thoughts are dangerous. As the person’s fear of such thoughts increases, the thoughts begin to occur more frequently and they, too, become obsessions.

Page 167

In support of this explanation, studies have found that people with obsessive-compulsive disorder have intrusive thoughts more often than other people, resort to more elaborate neutralizing strategies, and experience reductions in anxiety after using neutralizing techniques (Jacob et al, 2014; Shafran, 2005; Salkovskis et al., 2003).

Personal knowledge The HBO hit series Girls follows the struggles of Hannah Horvath and her friends as they navigate their twenties, “one mistake at a time.” The show’s creator and star, Lena Dunham, says that Hannah’s difficulties often are inspired by her own real-life experiences, including her childhood battle with OCD and anxiety.

Although everyone sometimes has undesired thoughts, only some people develop obsessive-compulsive disorder. Why do these individuals find such normal thoughts so disturbing to begin with? Researchers have found that this population tends (1) to be more depressed than other people (Klenfeldt et al., 2014; Hong et al., 2004), (2) to have exceptionally high standards of conduct and morality (Whitton, Henry, & Grisham, 2014; Rachman, 1993), (3) to have an inflated sense of responsibility in life and believe that their intrusive negative thoughts are equivalent to actions and capable of causing harm (Lawrence & Williams, 2011; Steketee et al., 2003), and (4) generally to believe that they should have perfect control over all of their thoughts and behaviors (Gelfand & Radomsky, 2013; Coles et al., 2005).

Cognitive therapists help clients focus on the cognitive processes involved in their obsessive-compulsive disorder. Initially, they educate the clients, pointing out how misinterpretations of unwanted thoughts, an excessive sense of responsibility, and neutralizing acts help produce and maintain their symptoms. The therapists then guide the clients to identify, challenge, and change their distorted cognitions. It appears that cognitive techniques of this kind often help reduce the number and impact of obsessions and compulsions (Franklin & Foa, 2014; Rufer et al., 2005).

While the behavioral approach (exposure and response prevention) and the cognitive approach have each been of help to clients with obsessive-compulsive disorder, some research suggests that a combination of the two approaches is often more effective than either intervention alone (Grayson, 2014; McKay et al., 2010; Sookman & Steketee, 2010). In such cognitive-behavioral treatments, clients are first taught to view their obsessive thoughts as inaccurate occurrences rather than as valid and dangerous cognitions for which they are responsible and upon which they must act. As they become better able to identify and recognize the thoughts for what they are, they also become less inclined to act on them, more willing to subject themselves to the rigors of exposure and response prevention, and more likely to make gains using that behavioral technique.

The Biological Perspective

Family pedigree studies provided the earliest clues that obsessive-compulsive disorder may be linked in part to biological factors (Lambert & Kinsley, 2010). Studies of twins found that if one identical twin has this disorder, the other twin also develops it in 53 percent of cases. In contrast, among fraternal twins (twins who share half rather than all of their genes), both twins display the disorder in only 23 percent of the cases. In short, the more similar the gene composition of two individuals, the more likely both are to experience obsessive-compulsive disorder, if indeed one of them displays the disorder.

In recent years, two lines of research have uncovered more direct evidence that biological factors play a key role in obsessive-compulsive disorder, and promising biological treatments for the disorder have been developed as well. This research points to (1) abnormally low activity of the neurotransmitter serotonin (2) abnormal functioning in key regions of the brain.

Abnormal Serotonin ActivitySerotonin, like GABA and norepinephrine, is a brain chemical that carries messages from neuron to neuron. The first clue to its role in obsessive-compulsive disorder was, once again, a surprising finding by clinical researchers—this time that two antidepressant drugs, clomipramine and fluoxetine (Anafranil and Prozac), reduce obsessive and compulsive symptoms (Bokor & Anderson, 2014; Stein & Fineberg, 2007). Since these particular drugs increase serotonin activity, some researchers concluded that the disorder might be caused by low serotonin activity. In fact, only those antidepressant drugs that increase serotonin activity help in cases of obsessive-compulsive disorder; antidepressants that mainly affect other neurotransmitters typically have little or no effect on it (Jenike, 1992).

serotonin A neurotransmitter whose abnormal activity is linked to depression, obsessive-compulsive disorder, and eating disorders.

serotonin A neurotransmitter whose abnormal activity is linked to depression, obsessive-compulsive disorder, and eating disorders.

Page 168

Although serotonin is the neurotransmitter most often cited in explanations of obsessive-compulsive disorder, recent studies have suggested that other neurotransmitters, particularly glutamate, GABA, and dopamine, may also play important roles in the development of the disorder (Bokor & Anderson, 2014; Spooren et al., 2010). Some researchers even argue that, with regard to obsessive-compulsive disorder, serotonin may act largely as a neuromodulator, a chemical whose primary function is to increase or decrease the activity of other key neurotransmitters.

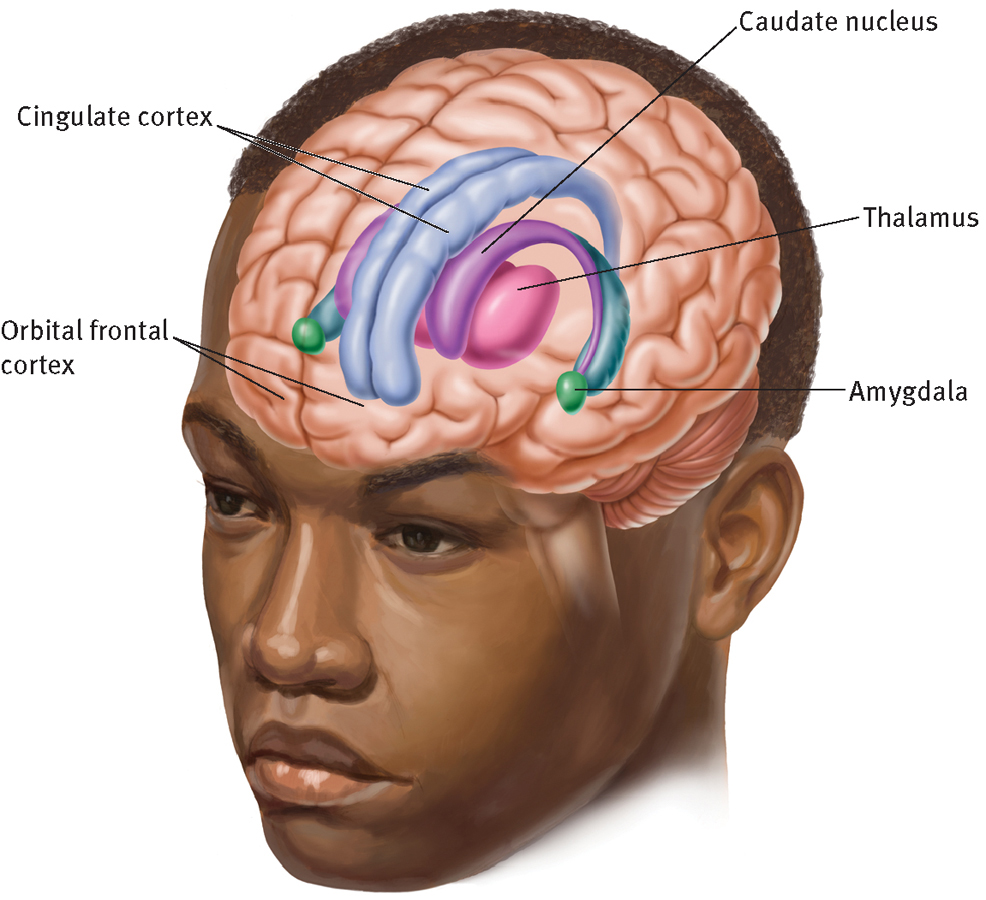

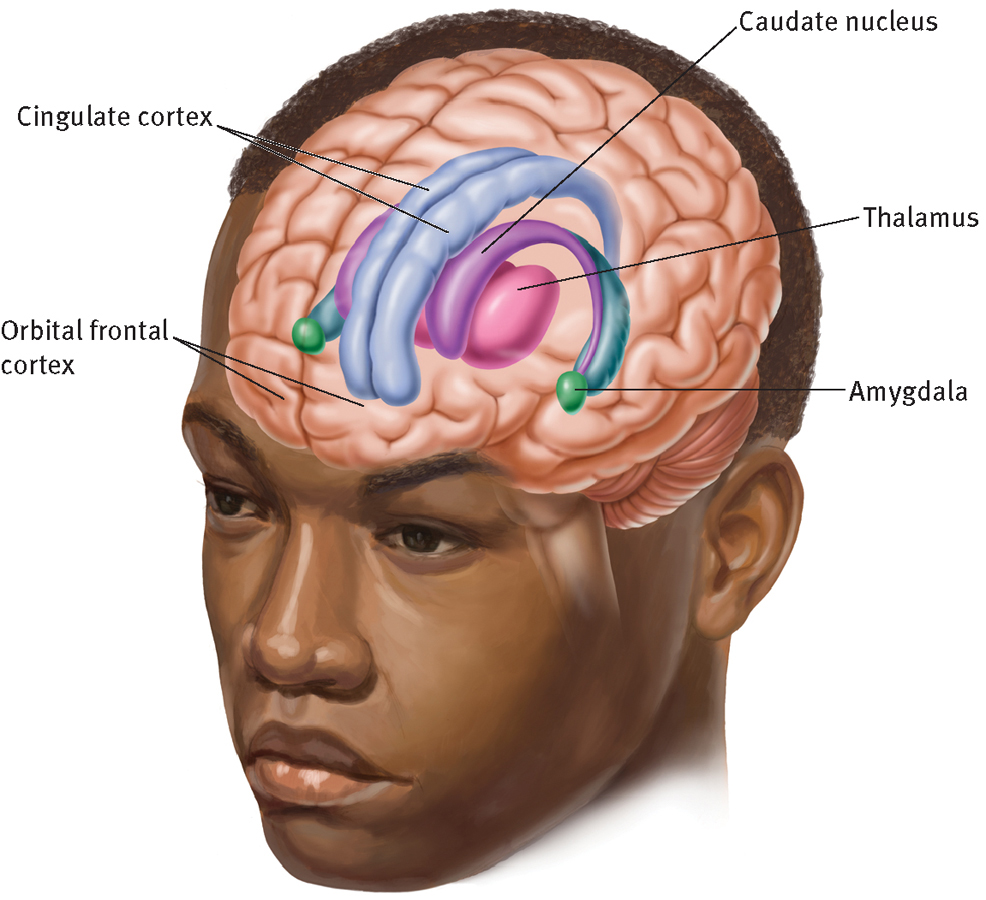

Abnormal Brain Structure and FunctioningAnother line of research has linked obsessive-compulsive disorder to the abnormal functioning of specific regions of the brain, particularly the orbitofrontal cortex (just above each eye) and the caudate nuclei (structures located within the brain region known as the basal ganglia). These regions are part of a brain circuit that usually converts sensory information into thoughts and actions (Craig & Chamberlain, 2010; Stein & Fineberg, 2007). The circuit begins in the orbitofrontal cortex, where sexual, violent, and other primitive impulses normally arise. These impulses next move on to the caudate nuclei, which act as filters that send only the most powerful impulses on to the thalamus, the next stop on the circuit (see Figure 5-7). If impulses reach the thalamus, the person is driven to think further about them and perhaps to act. Many theorists now believe that either the orbitofrontal cortex or the caudate nuclei of some people are too active, leading to a constant eruption of troublesome thoughts and actions (Endrass et al., 2011; Lambert & Kinsley, 2010). Additional parts of this brain circuit have also been identified in recent years, including the cingulate cortex and, yet again, the amygdala (Via et al., 2014; Stein & Fineberg, 2007). It may turn out that these regions also play key roles in obsessive-compulsive disorder.

orbitofrontal cortex A region of the brain in which impulses involving excretion, sexuality, violence, and other primitive activities normally arise.

orbitofrontal cortex A region of the brain in which impulses involving excretion, sexuality, violence, and other primitive activities normally arise.

caudate nuclei Structures in the brain, within the region known as the basal ganglia, that help convert sensory information into thoughts and actions.

caudate nuclei Structures in the brain, within the region known as the basal ganglia, that help convert sensory information into thoughts and actions.

Figure 5.7: figure 5-7

The biology of obsessive-compulsive disorder

Brain structures that have been linked to obsessive-compulsive disorder include the orbitofrontal cortex, caudate nucleus, thalamus, amygdala, and cingulate cortex. The structures may be too active in people with the disorder.

In support of this brain circuit explanation, medical scientists have observed for years that obsessive-compulsive symptoms do sometimes arise or subside after the orbitofrontal cortex, caudate nuclei, or other regions in the circuit are damaged by accident or illness (Hofer et al., 2013; Coetzer, 2004). Similarly, brain scan studies have shown that the caudate nuclei and the orbitofrontal cortex of research participants with obsessive-compulsive disorder are more active than those of control participants (Marsh et al., 2014; Baxter et al., 2001, 1990). Some research further suggests that the serotonin and brain circuit abnormalities that characterize obsessive-compulsive disorder are at least partly the result of genetic inheritance (Nicolini et al., 2011).

The serotonin and brain circuit explanations may themselves be linked. It turns out that serotonin—along with the neurotransmitters glutamate, GABA, and dopamine—plays a key role in the operation of the orbitofrontal cortex, caudate nuclei, and other parts of the brain circuit; certainly abnormal activity by one or more of these neurotransmitters could be contributing to the improper functioning of the circuit.

Page 169

BETWEEN THE LINES

Beethoven is said to have habitually dipped his head in cold water before trying to compose music.

According to surveys, almost half of adults double back after leaving home to make sure they have turned off an appliance.

More than half of all people who use an alarm clock check it repeatedly to be sure they’ve set it.

Biological TherapiesEver since researchers first discovered that particular antidepressant drugs help to reduce obsessions and compulsions, these drugs have been used to treat obsessive-compulsive disorder (Bokor & Anderson, 2014; Simpson, 2010). We now know that the drugs not only increase brain serotonin activity but also help produce more normal activity in the orbitofrontal cortex and caudate nuclei (McCabe & Mishor, 2011; Stein & Fineberg, 2007). Studies have found that clomipramine (Anafranil), fluoxetine (Prozac), fluvoxamine (Luvox), and similar antidepressant drugs bring improvement to between 50 and 80 percent of those with obsessive-compulsive disorder (Bareggi et al., 2004). The obsessions and compulsions do not usually disappear totally, but on average they are cut almost in half within 8 weeks of treatment (DeVeaugh-Geiss et al., 1992). People who are treated with such drugs alone, however, tend to relapse if their medication is stopped. Thus, more and more individuals with obsessive-compulsive disorder are now being treated by a combination of behavioral, cognitive, and drug therapies. According to research, such combinations often yield higher levels of symptom reduction and bring relief to more clients than do each of the approaches alone—improvements that may continue for years (Romanelli et al., 2014; Simpson et al., 2013).

Obviously, the treatment picture for obsessive-compulsive disorder has improved greatly over the past 15 years, and indeed, this disorder is now helped by several forms of treatment, often used in combination. In fact, some studies suggest that the behavioral, cognitive, and biological approaches may ultimately have the same effect on the brain. In these investigations, both participants who responded to cognitive-behavioral treatments and those who responded to antidepressant drugs showed marked reductions in activity in the caudate nuclei and other parts of the obsessive-compulsive brain circuit (Jabr, 2013; Freyer et al., 2011; Baxter et al., 2000, 1992).

Obsessive-Compulsive-Related Disorders: Finding a Diagnostic Home

Many people perform particular patterns of repetitive and excessive behavior that greatly disrupt their lives. Among the most common such patterns are excessive appearance-checking, hoarding, hair-pulling, skin-picking, shopping, exercising, video game–playing, and sex. Over the years, clinicians have tried to figure out how to best think about and classify these patterns. At various times, the disorders have been called “excessive behaviors,” “repetitive behaviors,” “habit disorders,” “addictions,” and “impulse-control disorders.” In recent years, however, a growing number of clinical researchers have linked the patterns to obsessive-compulsive disorder, based on the driven nature of the behaviors and the obsessive-like concerns that typically trigger the behaviors. They have used the term “obsessive-compulsive spectrum disorders” to describe such patterns (Hollander et al., 2011).

A messy aftermath This man prepares to clean out his mother’s home after her death. This is not an easy task—emotionally or physically—under the best of circumstances, but it is particularly difficult in this instance: his mother had suffered from hoarding disorder.

Following the lead of these researchers, DSM-5 has created the group name obsessive-compulsive-related disorders and assigned four of these patterns to that group: hoarding disorder, trichotillomania (hair-pulling disorder), excoriation (skin-picking) disorder, and body dysmorphic disorder. Collectively, these four disorders are displayed by at least 5 percent of all people (Frost et al., 2012; Keuthen et al., 2012, 2010; Wolrich, 2011; Duke et al., 2009).

obsessive-compulsive-related disorders Disorders in which obsessive-like concerns drive people to repeatedly and excessively perform certain patterns of behavior that greatly disrupt their lives.

obsessive-compulsive-related disorders Disorders in which obsessive-like concerns drive people to repeatedly and excessively perform certain patterns of behavior that greatly disrupt their lives.

Page 170

People who display hoarding disorder feel that they must save items, and they become very distressed if they try to discard them (APA, 2013). These feelings make it difficult for them to part with possessions, resulting in an extraordinary accumulation of items that clutters their lives and living areas (see Table 5-11). This pattern causes the individuals significant distress and may greatly impair their personal, social, or occupational functioning (Jabr, 2013; Frost et al., 2012; Mataix-Cols & Pertusa, 2012). It is common for them to wind up with numerous useless and valueless items, from junk mail to broken objects to unused clothes. Parts of their homes may become inaccessible because of the clutter. For example, sofas, kitchen appliances, or beds may be unusable. In addition, the pattern often results in fire hazards, unhealthful sanitation conditions, or other dangers.

hoarding disorder A disorder in which individuals feel compelled to save items and become very distressed if they try to discard them, resulting in an excessive accumulation of items.

hoarding disorder A disorder in which individuals feel compelled to save items and become very distressed if they try to discard them, resulting in an excessive accumulation of items.

People with trichotillomania, also known as hair-pulling disorder, repeatedly pull out hair from their scalp, eyebrows, eyelashes, or other parts of the body (see again Table 5-11) (APA, 2013). The disorder usually centers on just one or two of these body sites, most often the scalp. Typically, those with the disorder pull one hair at a time. It is common for anxiety or stress to trigger or accompany the hair-pulling behavior. Some sufferers follow specific rituals as they pull their hair, including pulling until the hair feels “just right” and selecting certain types of hairs for pulling (Keuthen et al., 2012; Mansueto & Rogers, 2012). Because of the distress, impairment, or embarrassment caused by this behavior, the individuals often try to reduce or stop the hair-pulling. The term “trichotillomania” is derived from the Greek for “frenzied hair-pulling.”

trichotillomania A disorder in which people repeatedly pull out hair from their scalp, eyebrows, eyelashes, or other parts of the body. Also called hair-pulling disorder.

trichotillomania A disorder in which people repeatedly pull out hair from their scalp, eyebrows, eyelashes, or other parts of the body. Also called hair-pulling disorder.

People with excoriation (skin-picking) disorder keep picking at their skin, resulting in significant sores or wounds (APA, 2013). Like those with hair-pulling disorder, they often try to reduce or stop the behavior. Most sufferers pick with their fingers and center their picking on one area, most often the face (Grant et al., 2012; Odlaug & Grant, 2012). Other common areas of focus include the arms, legs, lips, scalp, chest, and extremities such as fingernails and cuticles. The behavior is typically triggered or accompanied by anxiety or stress.

excortiation disorder A disorder in which people repeatedly pick at their skin, resulting in significant sores or wounds. Also called skin-picking disorder.

excortiation disorder A disorder in which people repeatedly pick at their skin, resulting in significant sores or wounds. Also called skin-picking disorder.

People with body dysmorphic disorder become preoccupied with the belief that they have a particular defect or flaw in their physical appearance (see again Table 5-11). Actually, the perceived defect or flaw is imagined or greatly exaggerated in the person’s mind (APA, 2013). Such beliefs drive the individuals to repeatedly check themselves in the mirror, groom themselves, pick at the perceived flaw, compare themselves with others, seek reassurance, or perform other, similar behaviors. Here too, those with the problem experience significant distress or impairment.

body dysmorphic disorder A disorder in which individuals become preoccupied with the belief that they have certain defects or flaws in their physical appearance. Such defects or flaws are imagined or greatly exaggerated.

body dysmorphic disorder A disorder in which individuals become preoccupied with the belief that they have certain defects or flaws in their physical appearance. Such defects or flaws are imagined or greatly exaggerated.

Table 5.11: table: 5-11Dx Checklist

|

|

|

|

Persons are repeatedly unable to give up or throw out their possessions, even worthless ones, because they feel a need to save them and want to avoid the discomfort of disposal. |

|

|

Persons accumulate an extra ordinary number of possessions that severely clutter and crowd their homes. |

|

|

Significant distress or impairment. |

Trichotillomania (Hair-Pulling Disorder) |

|

|

Individuals repeatedly pull out their hair. |

|

|

Despite attempts to stop, individuals are unable to stop this practice. |

|

|

Significant distress or impairment. |

|

|

|

|

Persons are preoccupied with having defect(s) or flaw(s) in their appearance that seem at most trivial to others. |

|

|

In response to their concerns, the persons repeatedly perform certain behaviors (e.g., check their appearance in mirrors) or mental acts (e.g., compare their appearance with that of others). |

|

|

Significant distress or impairment. |

Information from: APA, 2013. |

BETWEEN THE LINES

Surgeons report a 31% increase in plastic surgery requests as a result of patients wanting to look good on social media.

Cosmetic surgery now accounts for 73% of all plastic surgery operations, a rise from 62% a year ago.

Body dysmorphic disorder is the obsessive-compulsive-related disorder that has received the most study to date. Researchers have found that, most often, individuals with this problem focus on wrinkles; spots on the skin; excessive facial hair; swelling of the face; or a misshapen nose, mouth, jaw, or eyebrow (Week et al., 2012; Marques et al., 2011). Some worry about the appearance of their feet, hands, breasts, penis, or other body parts (see PsychWatch on page 173). Still others, like the woman described here, are concerned about bad odors coming from sweat, breath, genitals, or the rectum (Rocca et al., 2010).

Page 171

A woman of 35 had for 16 years been worried that her sweat smelled terrible…. For fear that she smelled, for 5 years she had not gone out anywhere except when accompanied by her husband or mother. She had not spoken to her neighbors for 3 years…. She avoided cinemas, dances, shops, cafes, and private homes…. Her husband was not allowed to invite any friends home; she constantly sought reassurance from him about her smell…. Her husband bought all her new clothes as she was afraid to try on clothes in front of shop assistants. She used vast quantities of deodorant and always bathed and changed her clothes before going out, up to 4 times daily.

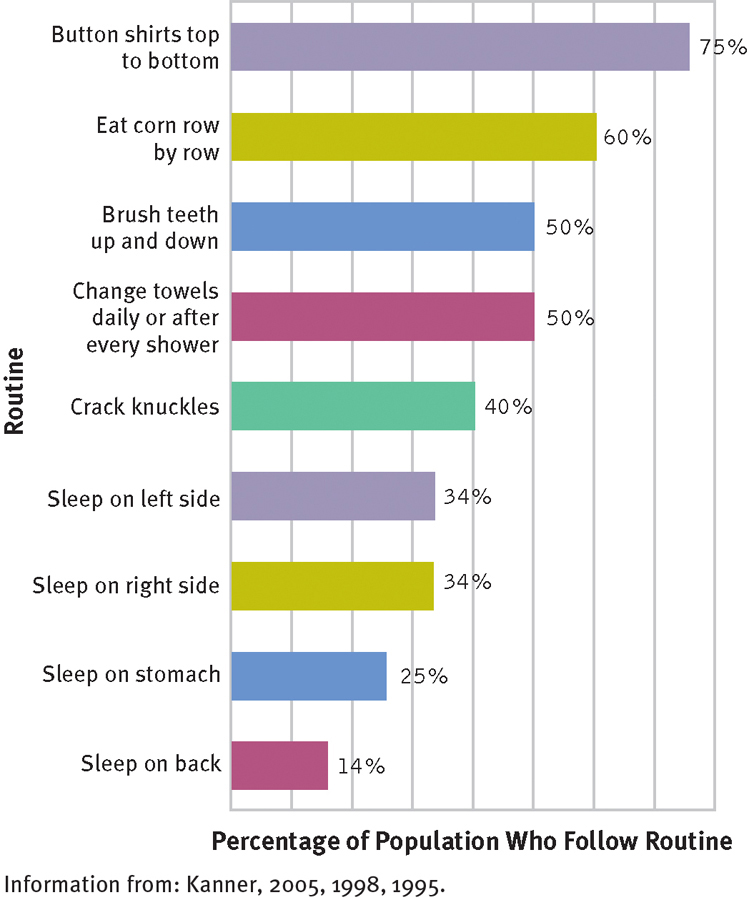

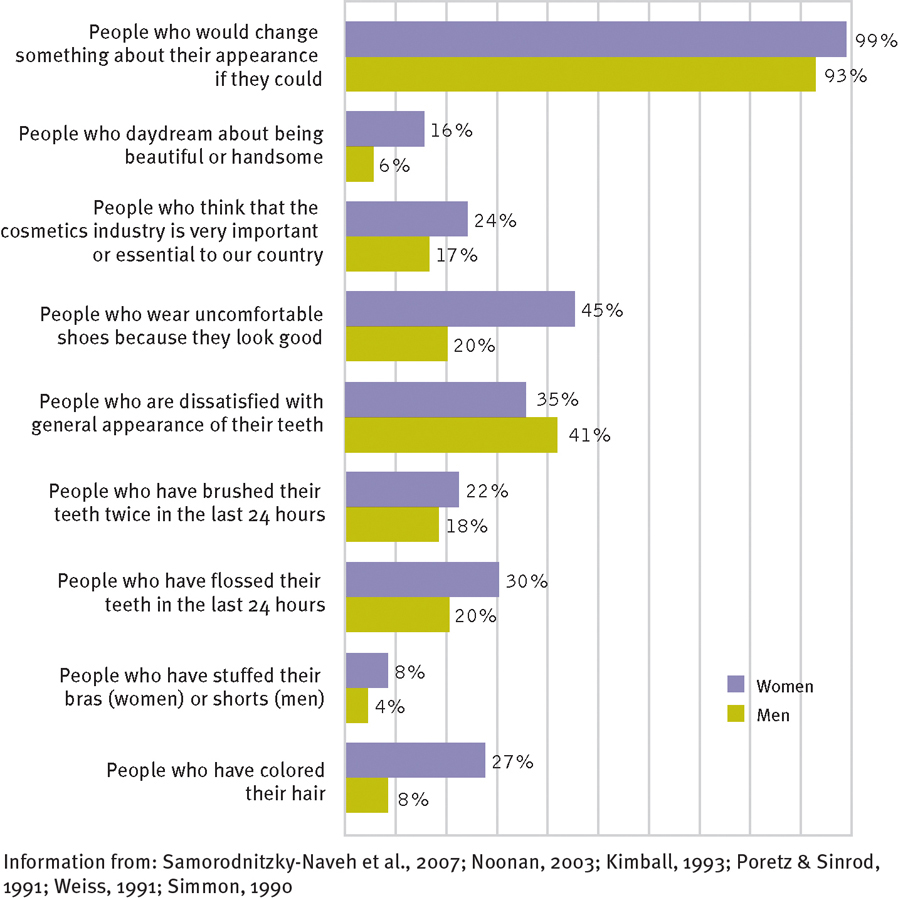

Of course, it is common in our society to worry about appearance (see Figure 5-8). Many teenagers and young adults worry about acne, for instance. The concerns of people with body dysmorphic disorder, however, are extreme. Sufferers may severely limit contact with other people, be unable to look others in the eye, or go to great lengths to conceal their “defects”—say, always wearing sunglasses to cover their supposedly misshapen eyes (Didie et al., 2010; Phillips, 2005). As many as half of people with the disorder seek plastic surgery or dermatology treatment, and often they feel worse rather than better afterward (McKay et al., 2008). A large number are housebound, and more than 10 percent may attempt suicide (Buhlmann et al., 2010; Phillips et al., 1993).

Figure 5.8: figure 5-8

“Mirror, mirror, on the wall …”

People with body dysmorphic disorder are not the only ones who have concerns about their appearance. Surveys find that in our appearance-conscious society, large percentages of people regularly think about and try to change the way they look.

Page 172

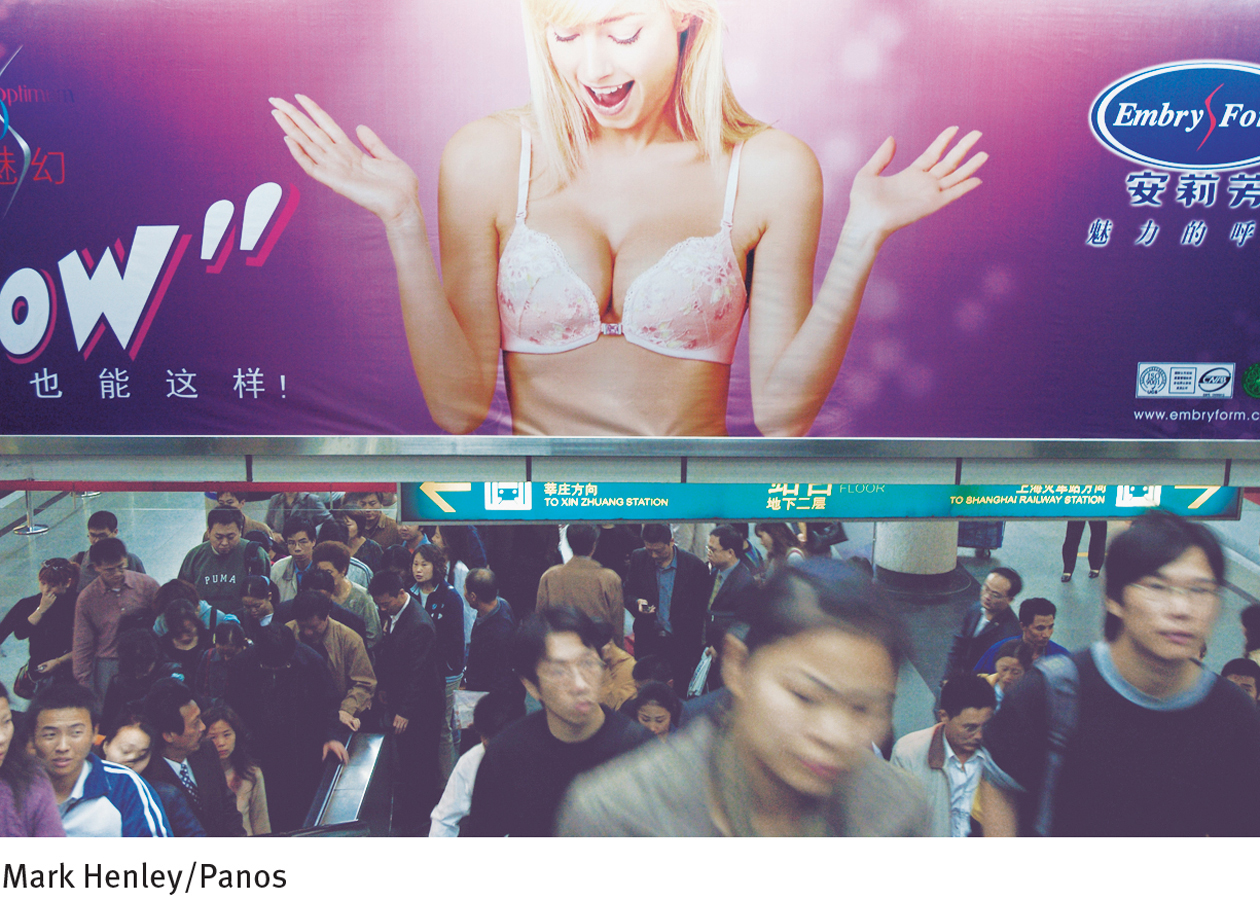

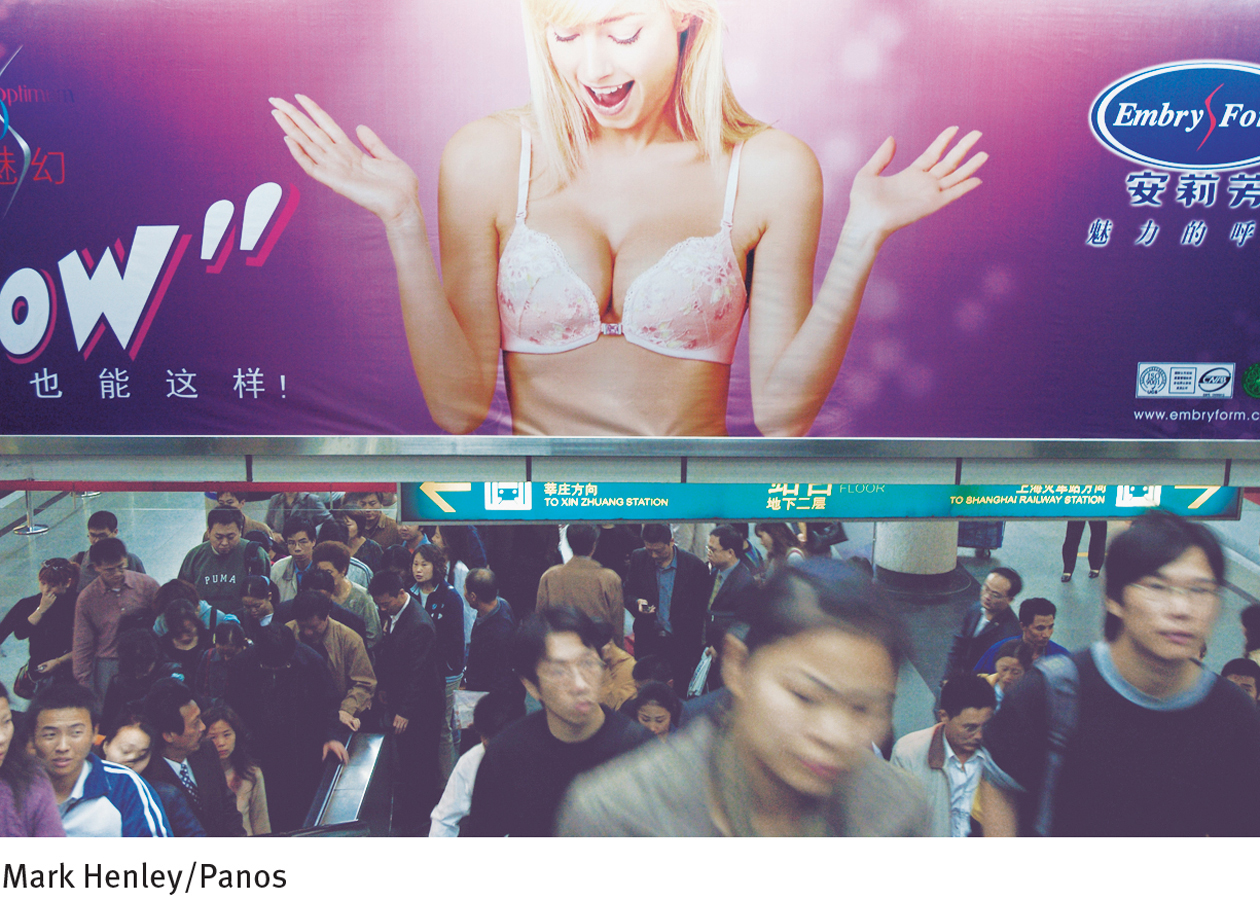

Worldwide influence A lingerie ad in a subway station in Shanghai, China, displays a woman in a push-up bra. As West meets East, Asian women have been bombarded by ads encouraging them to make Western-like changes to their various body parts. Perhaps not so coincidentally, cases of body dysmorphic disorder among Asians are becoming more and more similar to those among Westerners.

As with the other obsessive-compulsive-related disorders, theorists typically account for body dysmorphic disorder by using the same kinds of explanations, both psychological and biological, that have been applied to obsessive-compulsive disorder (Witthöft & Hiller, 2010). Similarly, clinicians typically treat clients with this disorder by applying the kinds of treatment used with obsessive-compulsive disorder, particularly antidepressant drugs, exposure and response prevention, and cognitive therapy (Krebs et al., 2012; Phillips & Rogers, 2011).

In one study, for example, 17 clients with this disorder were treated with exposure and response prevention. Over the course of 4 weeks, the clients were repeatedly reminded of their perceived physical defects and, at the same time, prevented from doing anything to help reduce their discomfort (such as checking their appearance) (Neziroglu et al., 2004, 1996). By the end of treatment, these individuals were less concerned with their “defects” and spent less time checking their body parts and avoiding social interactions.

Now that the body dysmorphic, hoarding, hair-pulling, and excoriation disorders are being grouped together in DSM-5 along with obsessive-compulsive disorder, it is hoped that they will be better researched, understood, and treated (Snowdon etal., 2012). The DSM-5 task force determined that the other excessive patterns (for example, shopping or sexual activity) need further study before a decision can be made about their inclusion in this same group.

obsession A persistent thought, idea, impulse, or image that is experienced repeatedly, feels intrusive, and causes anxiety.

obsession A persistent thought, idea, impulse, or image that is experienced repeatedly, feels intrusive, and causes anxiety. compulsion A repetitive and rigid behavior or mental act that a person feels driven to perform in order to prevent or reduce anxiety.

compulsion A repetitive and rigid behavior or mental act that a person feels driven to perform in order to prevent or reduce anxiety.

obsessive-compulsive disorder A disorder in which a person has recurrent and unwanted thoughts, a need to perform repetitive and rigid actions, or both.

obsessive-compulsive disorder A disorder in which a person has recurrent and unwanted thoughts, a need to perform repetitive and rigid actions, or both.

isolation An ego defense mechanism in which people unconsciously isolate and disown undesirable and unwanted thoughts, experiencing them as foreign intrusions.

isolation An ego defense mechanism in which people unconsciously isolate and disown undesirable and unwanted thoughts, experiencing them as foreign intrusions. undoing An ego defense mechanism whereby a person unconsciously cancels out an unacceptable desire or act by performing another act.

undoing An ego defense mechanism whereby a person unconsciously cancels out an unacceptable desire or act by performing another act. reaction formation An ego defense mechanism whereby a person suppresses an unacceptable desire by taking on a lifestyle that expresses the opposite desire.

reaction formation An ego defense mechanism whereby a person suppresses an unacceptable desire by taking on a lifestyle that expresses the opposite desire.

exposure and response prevention A behavioral treatment for obsessive-

exposure and response prevention A behavioral treatment for obsessive- neutralizing A person’s attempt to eliminate unwanted thoughts by thinking or behaving in ways that put matters right internally, making up for the unacceptable thoughts.

neutralizing A person’s attempt to eliminate unwanted thoughts by thinking or behaving in ways that put matters right internally, making up for the unacceptable thoughts.

serotonin A neurotransmitter whose abnormal activity is linked to depression, obsessive-

serotonin A neurotransmitter whose abnormal activity is linked to depression, obsessive- orbitofrontal cortex A region of the brain in which impulses involving excretion, sexuality, violence, and other primitive activities normally arise.

orbitofrontal cortex A region of the brain in which impulses involving excretion, sexuality, violence, and other primitive activities normally arise. caudate nuclei Structures in the brain, within the region known as the basal ganglia, that help convert sensory information into thoughts and actions.

caudate nuclei Structures in the brain, within the region known as the basal ganglia, that help convert sensory information into thoughts and actions.

obsessive-

obsessive- hoarding disorder A disorder in which individuals feel compelled to save items and become very distressed if they try to discard them, resulting in an excessive accumulation of items.

hoarding disorder A disorder in which individuals feel compelled to save items and become very distressed if they try to discard them, resulting in an excessive accumulation of items. trichotillomania A disorder in which people repeatedly pull out hair from their scalp, eyebrows, eyelashes, or other parts of the body. Also called hair-

trichotillomania A disorder in which people repeatedly pull out hair from their scalp, eyebrows, eyelashes, or other parts of the body. Also called hair- excortiation disorder A disorder in which people repeatedly pick at their skin, resulting in significant sores or wounds. Also called skin-

excortiation disorder A disorder in which people repeatedly pick at their skin, resulting in significant sores or wounds. Also called skin- body dysmorphic disorder A disorder in which individuals become preoccupied with the belief that they have certain defects or flaws in their physical appearance. Such defects or flaws are imagined or greatly exaggerated.

body dysmorphic disorder A disorder in which individuals become preoccupied with the belief that they have certain defects or flaws in their physical appearance. Such defects or flaws are imagined or greatly exaggerated.