6.3 Dissociative Disorders

As you have just read, people with acute and posttraumatic stress disorders may have symptoms of dissociation along with their other symptoms. They may, for example, feel dazed, have trouble remembering things, or have a sense of derealization. Symptoms of this kind are also on display in dissociative disorders, another group of disorders triggered by traumatic events (Armour et al., 2014). In fact, the memory difficulties and other dissociative symptoms found in these disorders are particularly intense, extensive, and disruptive. Moreover, in such disorders, dissociative reactions are the main or only symptoms. People with dissociative disorders do not typically have the significant arousal, negative emotions, sleep difficulties, and other problems that characterize acute and posttraumatic stress disorders. Nor are there clear physical factors at work in dissociative disorders.

dissociative disorders Disorders marked by major changes in memory that do not have clear physical causes.

dissociative disorders Disorders marked by major changes in memory that do not have clear physical causes.

Most of us experience a sense of wholeness and continuity as we interact with the world. We perceive ourselves as being more than a collection of isolated sensory experiences, feelings, and behaviors. In other words, we have an identity, a sense of who we are and where we fit in our environment. Memory is a key to this sense of identity, the link between our past, present, and future. Without a memory, we would always be starting over; with it, our life and our identity move forward. In dissociative disorders, one part of a person’s memory or identity becomes dissociated, or separated, from other parts of his or her memory or identity.

memory The faculty for recalling past events and past learning.

memory The faculty for recalling past events and past learning.

There are several kinds of dissociative disorders. People with dissociative amnesia are unable to recall important personal events and information. People with dissociative identity disorder, once known as multiple personality disorder, have two or more separate identities that may not always be aware of each other’s memories, thoughts, feelings, and behavior. And people with depersonalization-

Several famous books and movies have portrayed dissociative disorders. Two classics are The Three Faces of Eve and Sybil, each about a woman who developed multiple personalities after having been subject to traumatic events in childhood. The topic is so fascinating that most television drama series seem to include at least one case of dissociation every season, creating the impression that the disorders are very common. Many clinicians, however, believe that they are rare.

Dissociative Amnesia

People with dissociative amnesia are unable to recall important information, usually of a stressful nature, about their lives (APA, 2013). The loss of memory is much more extensive than normal forgetting and is not caused by physical factors such as a blow to the head (see Table 6-3). Typically, an episode of amnesia is directly triggered by a traumatic or upsetting event (Kikuchi et al., 2010).

dissociative amnesia A disorder marked by an inability to recall important personal events and information.

dissociative amnesia A disorder marked by an inability to recall important personal events and information.

Dissociative amnesia may be localized, selective, generalized, or continuous. In localized amnesia, the most common type of dissociative amnesia, a person loses all memory of events that took place within a limited period of time, almost always beginning with some very disturbing occurrence. A soldier, for example, may awaken a week after a horrific combat battle and be unable to recall the battle or any of the events surrounding it. She may remember everything that happened up to the battle, and may recall everything that has occurred over the past several days, but the events in between remain a total blank. The forgotten period is called the amnestic episode. During an amnestic episode, people may appear confused; in some cases they wander about aimlessly. They are already experiencing memory difficulties but seem unaware of them.

Why do many people question the authenticity of people who seem to lose their memories at times of severe stress?

People with selective amnesia, the second most common form of dissociative amnesia, remember some, but not all, events that took place during a period of time. If the combat soldier mentioned in the previous paragraph had selective amnesia, she might remember certain interactions or conversations that occurred during the battle, but not more disturbing events such as the death of a friend or the screams of enemy soldiers.

|

Dissociative Amnesia |

|

|---|---|

|

1. |

Person cannot recall important life- |

|

2. |

Significant distress or impairment. |

|

3. |

The symptoms are not caused by a substance or medical condition. |

|

Dissociative Identity Disorder |

|

|

1. |

Person experiences a disruption to his or her identity, as reflected by at least two separate personality states or experiences of possession. |

|

2. |

Person repeatedly experiences memory gaps regarding daily events, key personal information, or traumatic events, beyond ordinary forgetting. |

|

3. |

Significant distress or impairment. |

|

4. |

The symptoms are not caused by a substance or medical condition. |

|

Information from: APA, 2013. |

|

In some cases the loss of memory extends back to times long before the upsetting period. In addition to forgetting battle-

In the forms of dissociative amnesia just discussed, the period affected by the amnesia has an end. In continuous amnesia, however, forgetting continues into the present. The soldier might forget new and ongoing experiences as well as what happened before and during the battle.

These various forms of dissociative amnesia are similar in that the amnesia interferes mostly with a person’s memory of personal material. Memory for abstract or encyclopedic information usually remains. People with dissociative amnesia are as likely as anyone else to know the name of the president of the United States and how to read or drive a car.

Clinicians do not know how common dissociative amnesia is (Pope et al., 2007), but they do know that many cases seem to begin during serious threats to health and safety, as in wartime and natural disasters. Like the soldier in the earlier examples, combat veterans often report memory gaps of hours or days, and some forget personal information, such as their name and address (Bremner, 2002).

Childhood abuse, particularly child sexual abuse, can also trigger dissociative amnesia; indeed, in the 1990s there were many reports in which adults claimed to recall long-

PsychWatch

Repressed Childhood Memories or False Memory Syndrome?

Throughout the 1990s, reports of repressed childhood memory of abuse attracted much public attention. Adults with this type of dissociative amnesia seemed to recover buried memories of sexual and physical abuse from their childhood. A woman might claim, for example, that her father had sexually molested her repeatedly between the ages of 5 and 7. Or a young man might remember that a family friend had made sexual advances on several occasions when he was very young. Often the repressed memories surfaced during therapy for another problem.

Although the number of such claims has declined in recent years, experts remain split on this issue (Wolf & Nochajski, 2013; Birrell, 2011; Haaken & Reavey, 2010). Some believe that recovered memories are just what they appear to be—

If the alleged recovery of childhood memories is not what it appears to be, what is it? According to opponents of the concept, it may be a powerful case of suggestibility (Loftus & Cahill, 2007; Loftus, 2003, 2001). These theorists hold that the attention paid to the phenomenon by both clinicians and the public has led some therapists to make the diagnosis without sufficient evidence (Haaken & Reavey, 2010). The therapists may actively search for signs of early abuse in clients and even encourage clients to produce repressed memories (McNally & Garaerts, 2009). Certain therapists in fact use special memory recovery techniques, including hypnosis, regression therapy, journal writing, dream interpretation, and interpretation of bodily symptoms. Perhaps some clients respond to the techniques by unknowingly forming false memories of abuse. The apparent memories may then become increasingly familiar to them as a result of repeated therapy discussions of the alleged incidents.

Of course, repressed memories of childhood sexual abuse do not emerge only in clinical settings. Many individuals come forward on their own. Opponents of the repressed memory concept explain these cases by pointing to various books, articles, Web sites, and television shows that seem to validate repressed memories of childhood abuse (Haaken & Reavey, 2010; Loftus, 1993). Still other opponents of the repressed memory concept believe that, for biological or other reasons, some individuals are more prone than others to experience false memories—

It is important to recognize that the experts who question the recovery of repressed childhood memories do not in any way deny the problem of child sexual abuse. In fact, proponents and opponents alike are greatly concerned that the public may take this debate to mean that clinicians have doubts about the scope of the problem of child sexual abuse. Whatever may be the final outcome of the repressed memory debate, the problem of childhood sexual abuse is all too real and all too common.

The personal impact of dissociative amnesia depends on how much is forgotten. Obviously, an amnestic episode of two years is more of a problem than one of two hours. Similarly, an amnestic episode during which a person’s life changes in major ways causes more difficulties than one that is quiet.

An extreme version of dissociative amnesia is called dissociative fugue. Here persons not only forget their personal identities and details of their past lives but also flee to an entirely different location. Some people travel a short distance and make few social contacts in the new setting (APA, 2013). Their fugue may be brief—

dissociative fugue A form of dissociative amnesia in which a person travels to a new location and may assume a new identity, simultaneously forgetting his or her past.

dissociative fugue A form of dissociative amnesia in which a person travels to a new location and may assume a new identity, simultaneously forgetting his or her past.

On January 17, 1887, [the Reverend Ansel Bourne, of Greene, R.I.] drew 551 dollars from a bank in Providence with which to pay for a certain lot of land in Greene, paid certain bills, and got into a Pawtucket horsecar. This is the last incident which he remembers. He did not return home that day, and nothing was heard of him for two months. He was published in the papers as missing, and foul play being suspected, the police sought in vain his whereabouts. On the morning of March 14th, however, at Norristown, Pennsylvania, a man calling himself A. I. Brown who had rented a small shop six weeks previously, stocked it with stationery, confectionery, fruit and small articles, and carried on his quiet trade without seeming to any one unnatural or eccentric, woke up in a fright and called in the people of the house to tell him where he was. He said that his name was Ansel Bourne, that he was entirely ignorant of Norristown, that he knew nothing of shop keeping, and that the last thing he remembered—

(James, 1890, pp. 391–

Fugues tend to end abruptly. In some cases, as with Reverend Bourne, the person “awakens” in a strange place, surrounded by unfamiliar faces, and wonders how he or she got there. In other cases, the lack of personal history may arouse suspicion. Perhaps a traffic accident or legal problem leads police to discover the false identity; at other times friends search for and find the missing person. When people are found before their state of fugue has ended, therapists may find it necessary to ask them many questions about the details of their lives, repeatedly remind them who they are, and even begin psychotherapy before they recover their memories (Igwe, 2013; Mamarde et al., 2013). As these people recover their past, some forget the events of the fugue period.

The majority of people who go through a dissociative fugue regain most or all of their memories and never have a recurrence. Since fugues are usually brief and totally reversible, those who have experienced them tend to have few aftereffects. People who have been away for months or years, however, often do have trouble adjusting to the changes that took place during their flight. In addition, some people commit illegal or violent acts in their fugue state and later must face the consequences.

Dissociative Identity Disorder

Dissociative identity disorder is both dramatic and disabling, as we see in the case of Luisa:

Luisa was first brought in for treatment after she was found walking in circles by the side of the road in a suburban neighborhood near Denver. Agitated, malnourished, and dirty, this 30-

Once it became apparent that she fully believed what she was saying, the woman, who carried no identification of any kind, was transferred to a psychiatric hospital for observation. By the time she met with a therapist, she was no longer a young child speaking rapidly about a terrible family situation. She was now calling herself Luisa, and she spoke in slow, measured, and sad tones—

Luisa described how she had been sexually abused for years by her stepfather, starting when she was six. She said she had run away from home at the age of 15 and had not spoken since to either her mother or stepfather. She claimed that, although she had spent considerable time living on the streets over the years, she was currently living with her boyfriend, Tim, in a small apartment. However, when pressed, she was unable to say what Tim did for a living, nor could she provide his address or last name. Thus she remained in treatment.

Over the course of treatment, as her therapist continued to probe for details of her unhappy childhood and sexual abuse, Luisa became more and more agitated, until finally, she actually transformed back into 15-

Over the following several sessions, Luisa’s therapist wound up meeting still other personalities. One was Miss Johnson, a strict school principal who claimed to have taught Luisa when she was younger. Another was Roger—

BETWEEN THE LINES

In Their Words

“Be yourself; everyone else is already taken.”

Oscar Wilde

“There are lots of people who mistake their imagination for their memory.”

Josh Billings

A person with dissociative identity disorder, known in the past as multiple personality disorder, develops two or more distinct personalities, often called subpersonalities, or alternate personalities, each with a unique set of memories, behaviors, thoughts, and emotions (see again Table 6-3). At any given time, one of the subpersonalities takes center stage and dominates the person’s functioning. Usually one sub-

dissociative identity disorder A dissociative disorder in which a person develops two or more distinct personalities. Also known as multiple personality disorder.

dissociative identity disorder A dissociative disorder in which a person develops two or more distinct personalities. Also known as multiple personality disorder.

subpersonalities The two or more distinct personalities found in individuals suffering with dissociative identity disorder. Also known as alternate personalities.

subpersonalities The two or more distinct personalities found in individuals suffering with dissociative identity disorder. Also known as alternate personalities.

The transition from one subpersonality to another, called switching, is usually sudden and may be dramatic (Barlow & Chu, 2014). Luisa, for example, twisted her face and hunched her shoulders and body forward violently. Switching is usually triggered by a stressful event, although clinicians can also bring about the change with hypnotic suggestion.

Why might women be much more likely than men to receive a diagnosis of dissociative identity disorder?

Cases of dissociative identity disorder were first reported almost three centuries ago (Rieber, 2006, 2002). Many clinicians consider the disorder to be rare, but some reports suggest that it may be more common than was once thought (Dorahy et al., 2014). Most cases are first diagnosed in late adolescence or early adulthood, but more often than not, the symptoms actually began in early childhood after episodes of trauma or abuse (often sexual abuse) (Sar et al., 2014; Steele, 2011; Ross & Ness, 2010). Women receive this diagnosis at least three times as often as men.

BETWEEN THE LINES

More to the Story?

Recent reports, including claims by several colleagues who worked closely with the author of Sybil and with Sybil’s real-

How Do Subpersonalities Interact?How subpersonalities relate to or recall one another varies from case to case (Barlow & Chu, 2014). Generally, however, there are three kinds of relationships. In mutually amnesic relationships, the subpersonalities have no awareness of one another (Ellenberger, 1970). Conversely, in mutually cognizant patterns, each subpersonality is well aware of the rest. They may hear one another’s voices and even talk among themselves. Some are on good terms, while others do not get along at all.

In one-

Investigators used to believe that most cases of dissociative identity disorder involved two or three subpersonalities. Studies now suggest, however, that the average number of subpersonalities per patient is much higher—

In the case of “Eve White,” made famous in the book and movie The Three Faces of Eve, a woman had three subpersonalities—

The book was mistaken, however; this was not to be the end of Eve’s dissociation. In an autobiography 20 years later, she revealed that altogether 22 subpersonalities had come forth during her life, including 9 subpersonalities after Evelyn. Usually they appeared in groups of three, and so the authors of The Three Faces of Eve apparently never knew about her previous or subsequent subpersonalities. She has now overcome her disorder, achieving a single, stable identity, and has been known as Chris Sizemore for more than 35 years (Ramsland & Kuter, 2011; Sizemore, 1991).

How Do Subpersonalities Differ?As in Chris Sizemore’s case, subpersonalities often exhibit dramatically different characteristics. They may also have their own names and different identifying features, abilities and preferences, and even physiological responses.

IDENTIFYING FEATURESThe subpersonalities may differ in features as basic as age, gender, race, and family history, as in the case of Sybil Dorsett, whose disorder is described in the famous novel Sybil (Schreiber, 1973). According to the novel, Sybil displayed 17 subpersonalities, all with different identifying features. They included adults, a teenager, and even a baby. One subpersonality, Vicky, saw herself as attractive and blonde, while another, Peggy Lou, believed herself to be “a pixie with a pug nose.” Yet another, Mary, was plump with dark hair, and Vanessa was a tall, thin redhead. (It is worth noting that the accuracy of the real-

ABILITIES AND PREFERENCESAlthough memories of abstract or encyclopedic information are not usually affected in dissociative amnesia, they are often disturbed in dissociative identity disorder. It is not uncommon for the different subpersonalities to have different abilities: one may be able to drive, speak a foreign language, or play a musical instrument, while the others cannot (Coons & Bowman, 2001). Their handwriting can also differ. In addition, the subpersonalities usually have different tastes in food, friends, music, and literature. Chris Sizemore (“Eve”) later pointed out, “If I had learned to sew as one personality and then tried to sew as another, I couldn’t do it. Driving a car was the same. Some of my personalities couldn’t drive” (Sizemore & Pitillo, 1977, p. 4).

PHYSIOLOGICAL RESPONSESResearchers have discovered that subpersonalities may have physiological differences, such as differences in blood pressure levels and allergies (Spiegel, 2009; Putnam et al., 1990). A pioneering study looked at the brain activities of different subpersonalities by measuring their evoked potentials—that is, brain-

The evoked potential study also used control participants who pretended to have different subpersonalities. These normal individuals were instructed to create and rehearse alternate personalities. The brain-

BETWEEN THE LINES

Cultural Ties

Some clinical theorists argue that dissociative identity disorder is culture-

How Common Is Dissociative Identity Disorder?As you have seen, dissociative identity disorder has traditionally been thought of as rare. Some researchers even argue that many or all cases are iatrogenic—that is, unintentionally produced by practitioners (Lynn & Deming, 2010; Piper & Merskey, 2005, 2004). They believe that therapists create this disorder by subtly suggesting the existence of other personalities during therapy or by explicitly asking a patient to produce different personalities while under hypnosis. In addition, they believe, a therapist who is looking for multiple personalities may reinforce these patterns by displaying greater interest when a patient displays symptoms of dissociation.

These arguments seem to be supported by the fact that many cases of dissociative identity disorder first come to attention while the person is already in treatment for a less serious problem. But such is not true of all cases; many people seek treatment because they have noticed time lapses throughout their lives or because relatives and friends have observed their subpersonalities (Putnam, 2006, 2000).

The number of people diagnosed with dissociative identity disorder increased dramatically in the 1980s and 1990s, only to decrease again over the past 15 years (Paris, 2012). Not withstanding this decline, thousands of cases have now been diagnosed in the United States and Canada alone and some clinical theorists estimate that as much as 1 percent of the population in the United States and other Western countries displays the disorder (Dorahy et al, 2014).

What verdict is appropriate for accused criminals who experience dissociative identity disorder and whose crimes are committed by one of their subpersonalities?

For much of the twentieth century, cases of dissociative identity disorder may have been confused with cases of schizophrenia. Throughout that century, diagnoses of schizophrenia were applied, often incorrectly, to a wide range of unusual behavioral patterns, perhaps including dissociative identity disorder (Tschöke & Steinert, 2010). Under the stricter criteria of recent editions of the DSM, clinicians have been more accurate in diagnosing schizophrenia, allowing more cases of dissociative identity disorder to be recognized (Welburn et al., 2003). In addition, several diagnostic tests and structured interviews have been developed to help detect dissociative identity disorder (Dorahy et al, 2014; Sar et al., 2013). Despite such changes, however, many clinicians continue to question the legitimacy of this category.

How Do Theorists Explain Dissociative Amnesia and Dissociative Identity Disorder?

A variety of theories have been proposed to explain dissociative amnesia and dissociative identity disorder. Older explanations, such as those offered by psychodynamic and behavioral theorists, have not received much investigation (Merenda, 2008). However, newer viewpoints, which combine cognitive-

The Psychodynamic ViewPsychodynamic theorists believe that these dissociative disorders are caused by repression, the most basic ego defense mechanism: people fight off anxiety by unconsciously preventing painful memories, thoughts, or impulses from reaching awareness. Everyone uses repression to a degree, but people with dissociative amnesia and dissociative identity disorder are thought to repress their memories excessively (Henderson, 2010; Fayek, 2002).

In the psychodynamic view, dissociative amnesia is a single episode of massive repression. A person unconsciously blocks the memory of an extremely upsetting event to avoid the pain of facing it (Kikuchi et al., 2010). Repressing may be his or her only protection from overwhelming anxiety.

BETWEEN THE LINES

Most Commonly Forgotten Matters

|

Online passwords |

|

Where cell phone was left |

|

Where keys were left |

|

Where remote control was left |

|

Phone numbers |

|

Names |

|

Dream content |

|

Birthdays/anniversaries |

In contrast, dissociative identity disorder is thought to result from a lifetime of excessive repression (Howell, 2011; Wang & Jiang, 2007). Psychodynamic theorists believe that this continuous use of repression is motivated by traumatic childhood events, particularly abusive parenting (Baker, 2010; Ross & Ness, 2010). The novel Sybil, for example, describes young Sybil’s abuse at the hands of her disturbed mother, Hattie:

A favorite ritual … was to separate Sybil’s legs with a long wooden spoon, tie her feet to the spoon with dish towels, and then string her to the end of a light bulb cord, suspended from the ceiling. The child was left to swing in space while the mother proceeded to the water faucet to wait for the water to get cold. After muttering, “Well, it’s not going to get any colder,” she would fill the adult-

(Schreiber, 1973, p. 160)

According to psychodynamic theorists, children who experience such traumas may come to fear the dangerous world they live in and take flight from it by pretending to be another person who is looking on safely from afar. Abused children may also come to fear the impulses that they believe are the reasons for their excessive punishments. Whenever they experience “bad” thoughts or impulses, they unconsciously try to disown and deny them by assigning them to other personalities.

Most of the support for the psychodynamic explanation of dissociative identity disorder is drawn from case histories, which report such brutal childhood experiences as beatings, cuttings, burnings with cigarettes, imprisonment in closets, rape, and extensive verbal abuse (Ross & Ness, 2010). Yet some individuals with this disorder do not seem to have experiences of abuse in their background (Ross & Ness, 2010; Bliss, 1980). For example, Chris Sizemore, the subject of The Three Faces of Eve, has reported that her disorder first emerged during her preschool years after she witnessed two deaths and a horrifying accident within a three-

The Behavioral ViewBehaviorists believe that dissociation grows from normal memory processes such as drifting of the mind or forgetting (see PsychWatch on page 206). Specifically, they hold that dissociation is a response learned through operant conditioning (Casey, 2001). People who experience a horrifying event may later find temporary relief when their mind drifts to other subjects. For some, this momentary forgetting, leading to a drop in anxiety, increases the likelihood of future forgetting. In short, they are reinforced for the act of forgetting and learn—

State-

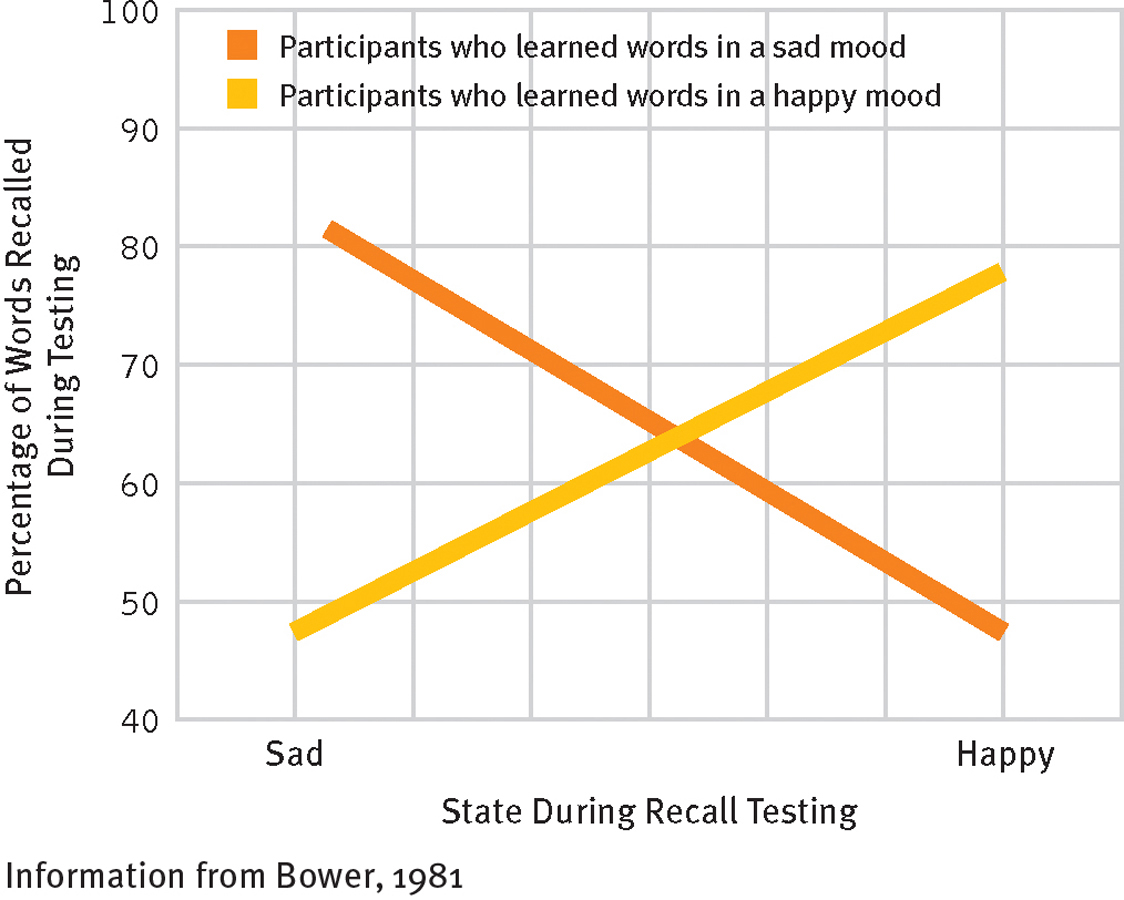

This link between state and recall is called state-dependent learning. It was initially observed in animals who learned things during experiments while under the influence of certain drugs (Ardjmand et al., 2011; Overton, 1966, 1964). Research with human participants later showed that state-

state-dependent learning Learning that becomes associated with the conditions under which it occurred, so that it is best remembered under the same conditions.

state-dependent learning Learning that becomes associated with the conditions under which it occurred, so that it is best remembered under the same conditions.

State-dependent learning

In one study, participants who learned a list of words while in a hypnotically induced happy state remembered the words better if they were in a happy mood when tested later than if they were in a sad mood. Conversely, participants who learned the words when in a sad mood recalled them better if they were sad during testing than if they were happy.

Might it be possible to use the principles of state-

What causes state-

Although people may remember certain events better in some arousal states than in others, most can recall events under a variety of states. However, perhaps people who are prone to develop dissociative disorders have state-

Self-

The parallels between hypnotic amnesia and the dissociative disorders we have been examining are striking (van der Kruijs et al., 2014; Terhune et al., 2011). Both are conditions in which people forget certain material for a period of time yet later remember it. And in both, the people forget without any insight into why they are forgetting or any awareness that something is being forgotten. These parallels have led some theorists to conclude that dissociative disorders may be a form of self-hypnosis in which people hypnotize themselves to forget unpleasant events (Dell, 2010). Dissociative amnesia may develop, for example, in people who, consciously or unconsciously, hypnotize themselves into forgetting horrifying experiences that have recently taken place in their lives. If the self-

self-hypnosis The process of hypnotizing oneself, sometimes for the purpose of forgetting unpleasant events.

self-hypnosis The process of hypnotizing oneself, sometimes for the purpose of forgetting unpleasant events.

PsychWatch

Peculiarities of Memory

Usually memory problems must interfere greatly with a person’s functioning before they are considered a sign of a disorder. Peculiarities of memory, on the other hand, fill our daily lives. Memory investigators have identified a number of these peculiarities—

Absentmindedness Often we fail to register information because our thoughts are focusing on other things. If we haven’t absorbed the information in the first place, it is no surprise that later we can’t recall it.

Déjà vu Almost all of us have at some time had the strange sensation of recognizing a scene that we happen upon for the first time. We feel sure we have been there before.

Jamais vu Sometimes we have the opposite experience: a situation or scene that is part of our daily life seems suddenly unfamiliar. “I knew it was my car, but I felt as if I’d never seen it before.”

The tip-

of- To have something on the tip of the tongue is an acute “feeling of knowing”: we are unable to recall some piece of information, but we know that we know it.the- tongue phenomenon Eidetic images Some people have such vivid visual afterimages that they can describe a picture in detail after looking at it just once. The images may be memories of pictures, events, fantasies, or dreams.

Memory while under anesthesia As many as 2 of every 1,000 anesthetized patients process enough of what is said in their presence during surgery to affect their recovery. In many such cases, the ability to understand language has continued under anesthesia, even though the patient cannot explicitly recall it.

Memory for music Even as a small child, Mozart could memorize and reproduce a piece of music after having heard it only once. While no one yet has matched the genius of Mozart, many musicians can mentally hear whole pieces of music, so that they can rehearse anywhere, far from their instruments.

Visual memory Most people recall visual information better than other kinds of information: they easily can bring to their mind the appearance of places, objects, faces, or the pages of a book. They almost never forget a face, yet they may well forget the name attached to it. Other people have stronger verbal memories: they remember sounds or words particularly well, and the memories that come to their minds are often puns or rhymes.

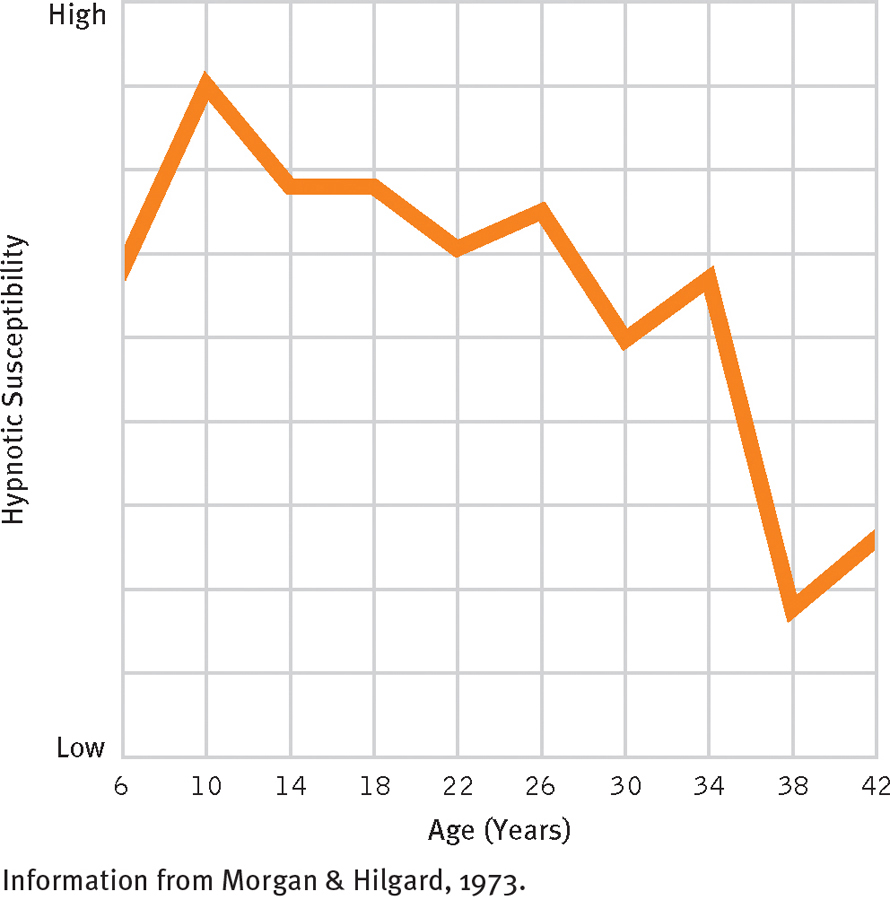

The self-

Hypnotic susceptibility and age

A person’s hypnotic susceptibility increases until just before adolescence, then generally declines.

There are different schools of thought about the nature of hypnosis (van der Kruijs et al., 2014; Dell, 2010; Lynn, Rhue, & Kirsch, 2010; Spanos & Coe, 1992). Some theorists see hypnosis as a special process, an out-

How Are Dissociative Amnesia and Dissociative Identity Disorder Treated?

As you have seen, people with dissociative amnesia often recover on their own. Only sometimes do their memory problems linger and require treatment. In contrast, people with dissociative identity disorder usually require treatment to regain their lost memories and develop an integrated personality. Treatments for dissociative amnesia tend to be more successful than those for dissociative identity disorder, probably because the former pattern is less complex.

How Do Therapists Help People with Dissociative Amnesia?The leading treatments for dissociative amnesia are psychodynamic therapy, hypnotic therapy, and drug therapy, although support for these interventions comes largely from case studies rather than controlled investigations (Gentile, Dillon, & Gillig, 2013; Maldonado & Spiegel, 2007, 2003). Psychodynamic therapists guide patients to search their unconscious in the hope of bringing forgotten experiences back to consciousness (Howell, 2011; Bartholomew, 2000). The focus of psychodynamic therapy seems particularly well suited to the needs of people with dissociative amnesia. After all, the patients need to recover lost memories, and the general approach of psychodynamic therapists is to try to uncover memories—

Another common treatment for dissociative amnesia is hypnotic therapy, or hypnotherapy (see Table 6-4). Therapists hypnotize patients and then guide them to recall their forgotten events (Degun-

hypnotic therapy A treatment in which the patient undergoes hypnosis and is then guided to recall forgotten events or perform other therapeutic activities. Also known as hypnotherapy.

hypnotic therapy A treatment in which the patient undergoes hypnosis and is then guided to recall forgotten events or perform other therapeutic activities. Also known as hypnotherapy.

|

Myth |

Reality |

|---|---|

|

Hypnosis relies on having a good imagination. |

Vivid imaginations are unrelated to hypnotizability. |

|

Hypnosis is dangerous. |

Hypnosis is no more distressing than a lecture. |

|

Hypnosis has something to do with a sleeplike state. |

Hypnotized people are fully awake. |

|

Hypnotized people lose control of themselves. |

Hypnotized people are perfectly capable of saying no. |

|

People remember more accurately under hypnosis. |

Hypnosis can help create false memories. |

|

Hypnotized people can be led to do immoral acts. |

Hypnotized people fully adhere to their usual values. |

|

Information from: Nash & Barnier, 2008; Nash, 2006, 2005, 2004, 2001. |

|

Sometimes injections of barbiturates such as sodium amobarbital (Amytal) or sodium pentobarbital (Pentothal) have been used to help patients with dissociative amnesia regain their lost memories. These drugs are often called “truth serums,” but actually their effect is to calm people and free their inhibitions, thus helping them to recall anxiety-

How Do Therapists Help People with Dissociative Identity Disorder?Unlike victims of dissociative amnesia, people with dissociative identity disorder do not typically recover without treatment. Treatment for this pattern is complex and difficult, much like the disorder itself. Therapists usually try to help the clients (1) recognize fully the nature of their disorder, (2) recover the gaps in their memory, and (3) integrate their subpersonalities into one functional personality (Gentile et al., 2013; Howell, 2011; North & Yutzy, 2005).

RECOGNIZING THE DISORDEROnce a diagnosis of dissociative identity disorder is made, therapists typically try to bond with the primary personality and with each of the subpersonalities (Howell, 2011). As bonds are formed, therapists try to educate patients and help them to recognize fully the nature of their disorder (Krakauer, 2001). Some therapists actually introduce the subpersonalities to one another, by hypnosis, for example, or by having patients look at videos of their other personalities (Howell, 2011; Ross & Gahan, 1988). A number of therapists have also found that group therapy helps to educate patients (Fine & Madden, 2000). In addition, family therapy may be used to help educate spouses and children about the disorder and to gather helpful information about the patient (Kluft, 2001, 2000).

RECOVERING MEMORIESTo help patients recover the missing pieces of their past, therapists typically use the same approaches applied in dissociative amnesia, including psychodynamic therapy, hypnotherapy, and drug treatment (Howell, 2011; Kluft, 2001, 1991, 1985). These techniques work slowly for patients with dissociative identity disorder, however, as some subpersonalities may keep denying experiences that the others recall. One of the subpersonalities may even assume a “protector” role to prevent the primary personality from suffering the pain of recollecting traumatic experiences.

INTEGRATING THE SUBPERSONALITIESThe final goal of therapy is to merge the different subpersonalities into a single, integrated identity. Integration is a continuous process that occurs throughout treatment until patients “own” all of their behaviors, emotions, sensations, and knowledge. Fusion is the final merging of two or more subpersonalities. Many patients distrust this final treatment goal, and their subpersonalities may see integration as a form of death (Howell, 2011; Kluft, 2001, 1999, 1991). Therapists have used a range of approaches to help merge subpersonalities, including psychodynamic, supportive, cognitive, and drug therapies (Cronin et al., 2014; Baker, 2010; Goldman, 1995).

fusion The final merging of two or more subpersonalities in dissociative identity disorder.

fusion The final merging of two or more subpersonalities in dissociative identity disorder.

Once the subpersonalities are integrated, further therapy is typically needed to maintain the complete personality and to teach social and coping skills that may help prevent later dissociations. In case reports, some therapists note high success rates (Dorahy et al., 2014: Howell, 2011), but others find that patients continue to resist full integration. A few therapists have in fact questioned the need for full integration.

Depersonalization-Derealization Disorder

As you read earlier, DSM-

depersonalization-derealization disorder A dissociative disorder marked by the presence of persistent and recurrent episodes of depersonalization, derealization, or both.

depersonalization-derealization disorder A dissociative disorder marked by the presence of persistent and recurrent episodes of depersonalization, derealization, or both.

BETWEEN THE LINES

In Their Words

“I was trying to daydream, but my mind kept wandering.”

Steven Wright, comedian

A 24-

[By] his second session, he … had begun to perceive [his girlfriend] in a distorted manner. He … hesitated before returning, because he wondered whether his therapist was really alive.

(Kluft, 1988, p. 580)

Like this graduate student, people experiencing depersonalization feel as though they have become separated from their body and are observing themselves from outside. Occasionally their mind seems to be floating a few feet above them—

BETWEEN THE LINES

In Their Words

“Reality is the leading cause of stress among those in touch with it.”

Lily Tomlin

In contrast to depersonalization, derealization is characterized by feeling that the external world is unreal and strange. Objects may seem to change shape or size; other people may seem removed, mechanical, or even dead. The graduate student, for example, saw other people as robots, perceived his girlfriend in a distorted manner, and hesitated to return for a second session of therapy because he wondered whether his therapist was really alive.

Depersonalization and derealization experiences by themselves do not indicate a depersonalization-

If you have ever experienced feelings of depersonalization or derealization, how did you explain them at the time?

The symptoms of depersonalization-