8.1 Treatments for Unipolar Depression

In the United States, around half of those with unipolar depression receive treatment from a mental health professional each year. Access to such treatment differs among ethnic and racial groups. As you read in the previous chapter, only 34 percent of depressed Hispanic Americans and 40 percent of depressed African Americans receive treatment, compared with 54 percent of depressed white Americans (González et al., 2010).

In addition, many people in therapy experience depressed feelings as part of another disorder, such as an eating disorder, or in association with changes or general problems that they are encountering in life. Thus much of the therapy being done today includes a focus on unipolar depression.

A variety of treatment approaches are currently in widespread use for unipolar depression. In this chapter, we first look at the psychological approaches, focusing on the psychodynamic, behavioral, and cognitive therapies. We then explore the socio-

Psychological Approaches

The psychological treatments used most often to combat unipolar depression come from the psychodynamic, behavioral, and cognitive schools of thought. Psycho-

What kinds of transference issues might psychodynamic therapists expect to see in treatment with depressed clients?

Psychodynamic TherapyBelieving that unipolar depression results from unconscious grief over real or imagined losses, compounded by excessive dependence on other people, psychodynamic therapists seek to help clients bring these underlying issues to consciousness and work them through. Using the arsenal of basic psychodynamic procedures, they encourage the depressed client to associate freely during therapy; suggest interpretations of the client’s associations, dreams, and displays of resistance and transference; and help the person review past events and feelings (Busch et al., 2004). Free association, for example, helped one man recall the early experiences of loss that, according to his therapist, had set the stage for his depression:

Among his earliest memories, possibly the earliest of all, was the recollection of being wheeled in his baby cart under the elevated train structure and left there alone. Another memory that recurred vividly during the analysis was of an operation around the age of five. He was anesthetized and his mother left him with the doctor. He recalled how he had kicked and screamed, raging at her for leaving him.

(Lorand, 1968, pp. 325–

BETWEEN THE LINES

In Their Words

“Given the choice between the experience of pain and nothing, I would choose pain.”

William Faulkner

Psychodynamic therapists expect that in the course of treatment depressed clients will eventually gain awareness of the losses in their lives, become less dependent on others, cope with losses more effectively, and make corresponding changes in their functioning. The transition of a therapeutic insight into a real-

The patient’s father was still living and in a nursing home, where the patient visited him regularly. On one occasion, he went to see his father full of high expectations, as he had concluded a very successful business transaction. As he began to describe his accomplishments to his father, however, the latter completely ignored his son’s remarks and viciously berated him for wearing a pink shirt, which he considered unprofessional. Such a response from the father was not unusual, but this time, as a result of the work that had been accomplished in therapy, the patient could objectively analyze his initial sense of disappointment and deep feeling of failure for not pleasing the older man. Although this experience led to a transient state of depression, it also revealed to the patient his whole dependent lifestyle—

(Bemporad, 1992, p. 291)

Despite successful case reports such as this, researchers have found that long-

Behavioral TherapyBehaviorists, whose theories of depression tie mood to the rewards in a person’s life, have developed corresponding treatments for unipolar depression. Most such treatments are modeled after the intervention proposed by Peter Lewinsohn, the behavioral theorist whose theory of depression was described in Chapter 7 (see pages 229, 231). In a typical behavioral approach, therapists (1) reintroduce depressed clients to pleasurable events and activities, (2) appropriately reward nondepressive behaviors and withhold rewards for depressive behaviors, and (3) help clients improve their social skills (Dimidjian et al., 2014).

First, the therapist selects activities that the client considers pleasurable, such as going shopping or taking photos, and encourages the person to set up a weekly schedule for engaging in them. Studies have shown that adding positive activities to a person’s life—

[Alicia] had never noticed a connection between her activities and her mood before. The depression had just felt like something that loomed over her, coloring everything. Worry and tension also seemed like constant companions. She now recognized that there were many subtle shifts in her mood, including some moments in which she experienced relief from the depression and accompanying worry. She felt content when she worked in her garden. After many weeks of avoiding friends, she felt relief when she had dinner with her friend Ellen…. As Alicia reviewed these activities with [her therapist], she also began to identify activities that she could increase during the upcoming week following their therapy session. Alicia thought that getting in touch with more friends could be helpful for her mood…. [She] decided that seeing Ellen again for coffee would be the most logical place to start…. Ellen’s social personality might … help Alicia reconnect with some of her other old friends over time. She planned to set up a coffee date with Ellen either on Wednesday after work or on the following Saturday morning. Alicia also enjoyed the contentment she usually felt when she worked in her pea patch. [The therapist] asked what she might do the next week in her garden. Alicia realized that she needed to get some mulch, so they wrote down a plan for that activity as well…. She agreed that she would report back to [the therapist] about how she felt during these activities in the next session.

(Martell et al., 2010)

While reintroducing pleasurable events into a client’s life, the therapist makes sure that the person’s various behaviors are reinforced correctly. Behaviorists argue that when people become depressed, their negative behaviors—

BETWEEN THE LINES

Self-

In 1991 the Gloucester branch of Depressives Anonymous ejected several members because they were too cheerful. Said the group chairperson, “Those with sensitive tender feelings have been put off by more robust members who have not always been depressives” (Shaw, 2004).

Finally, behavioral therapists may train clients in effective social skills (Thase, 2012; Hersen et al., 1984). In group therapy programs, for example, members may work together to improve eye contact, facial expression, posture, and other behaviors that send social messages.

These behavioral techniques seem to be of only limited help when just one of them is applied. In one classic study, for example, depressed people who were instructed to increase their pleasant activities showed no more improvement than those in a control group who were told simply to keep track of their activities (Hammen & Glass, 1975). However, when two or more behavioral techniques are combined, behavioral treatment does appear to reduce depressive symptoms, particularly if the depression is mild (Dimidjian et al, 2014; Martell et al., 2010; Jacobson et al., 2001, 1996). It is worth noting that Lewinsohn himself has combined behavioral techniques with cognitive strategies in recent years, in an approach similar to the cognitive-

Cognitive TherapyIn Chapter 7 you saw that Aaron Beck viewed unipolar depression as resulting from a pattern of negative thinking that may be triggered by current upsetting situations. Maladaptive attitudes lead people repeatedly to view themselves, their world, and their future in negative ways—

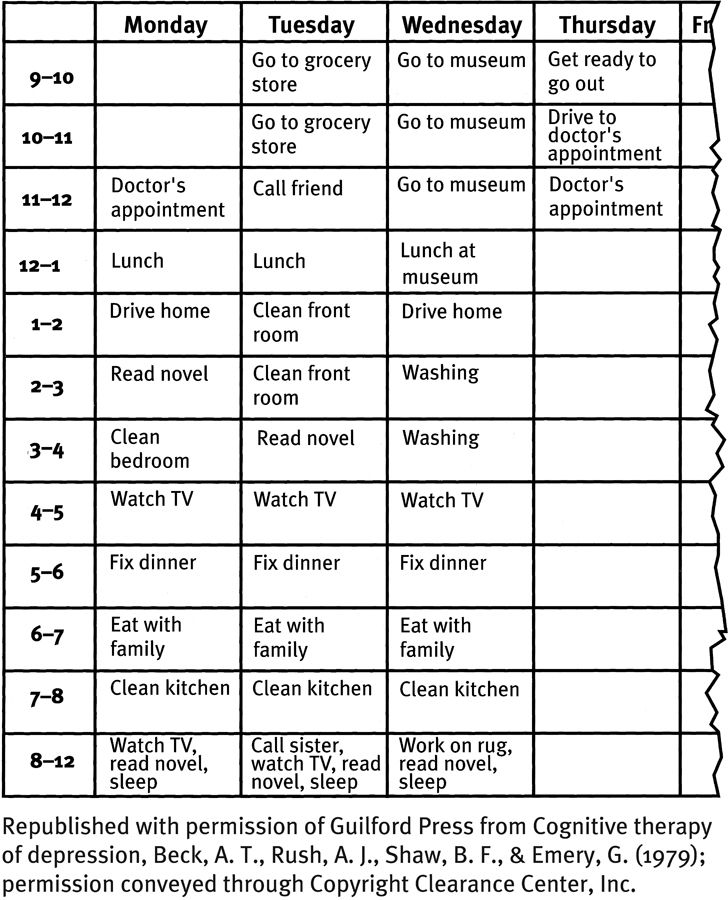

To help clients overcome this negative thinking, Beck has developed a treatment approach that he calls cognitive therapy. He uses this label because the approach is designed primarily to help clients recognize and change their negative cognitive processes and thus to improve their mood (Beck & Weishaar, 2014; Young et al., 2014). However, as you will see, the approach also includes a number of behavioral techniques (Figure 8-2), particularly as therapists try to get clients moving again and encourage them to try out new behaviors. Thus, many theorists consider this approach a cognitive-

cognitive therapy A therapy developed by Aaron Beck that helps people identify and change the maladaptive assumptions and ways of thinking that help cause their psychological disorders.

cognitive therapy A therapy developed by Aaron Beck that helps people identify and change the maladaptive assumptions and ways of thinking that help cause their psychological disorders.

Increasing activity

In the early stages of cognitive therapy for depression, the client and therapist prepare an activity schedule such as this. Activities as simple as watching television and calling a friend are specified.

|

Disorder |

Treatment |

Average Duration of Treatment |

Percent Improved by Treatment |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Major depressive disorder |

Cognitive/Cognitive- |

20 sessions |

60 |

|

|

Interpersonal psychotherapy |

20 sessions |

60 |

|

|

Antidepressant drugs |

Indefinite |

60 |

|

|

ECT |

9 sessions |

60 |

|

|

Vagus nerve stimulation |

1 session (plus follow- |

60 |

|

|

Transcranial magnetic stimulation |

25 sessions 60 |

60 |

|

Bipolar disorder |

Psychotropic drugs: Mood stabilizers, antipsychotics, and antidepressants |

Indefinite |

60 |

PHASE 1: INCREASING ACTIVITIES AND ELEVATING MOODUsing behavioral techniques to set the stage for cognitive treatment, therapists first encourage clients to become more active and confident. Clients spend time during each session preparing a detailed schedule of hourly activities for the coming week. As they become more active from week to week, their mood is expected to improve.

PHASE 2: CHALLENGING AUTOMATIC THOUGHTSOnce people are more active and feeling some emotional relief, cognitive therapists begin to educate them about their negative automatic thoughts. The individuals are instructed to recognize and record automatic thoughts as they occur and to bring their lists to each session. Therapist and client then test the reality behind the thoughts, often concluding that they are groundless. Beck offers the following exchange as an example of this sort of review:

|

Therapist: |

Why do you think you won’t be able to get into the university of your choice? |

|

Patient: |

Because my grades were really not so hot. |

|

Therapist: |

Well, what was your grade average? |

|

Patient: |

Well, pretty good up until the last semester in high school. |

|

Therapist: |

What was your grade average in general? |

|

Patient: |

A’s and B’s. |

|

Therapist: |

Well, how many of each? |

|

Patient: |

Well, I guess, almost all of my grades were A’s but I got terrible grades my last semester. |

|

Therapist: |

What were your grades then? |

|

Patient: |

I got two A’s and two B’s. |

|

Therapist: |

Since your grade average would seem to me to come out to almost all A’s, why do you think you won’t be able to get into the university? |

|

Patient: |

Because of competition being so tough. |

|

Therapist: |

Have you found out what the average grades are for admission to the college? |

|

Patient: |

Well, somebody told me that a B+ average would suffice. |

|

Therapist: |

Isn’t your average better than that? |

|

Patient: |

I guess so. |

|

(Beck et al., 1979, p. 153) |

|

PHASE 3: IDENTIFYING NEGATIVE THINKING AND BIASESAs people begin to recognize the flaws in their automatic thoughts, cognitive therapists show them how illogical thinking processes are contributing to these thoughts. The depressed student, for example, was using dichotomous (all-

PHASE 4: CHANGING PRIMARY ATTITUDESTherapists help clients change the maladaptive attitudes that set the stage for their depression in the first place. As part of the process, therapists often encourage clients to test their attitudes, as in the following therapy discussion:

|

Therapist: |

On what do you base this belief that you can’t be happy without a man? |

|

Patient: |

I was really depressed for a year and a half when I didn’t have a man. |

|

Therapist: |

Is there another reason why you were depressed? |

|

Patient: |

As we discussed, I was looking at everything in a distorted way. But I still don’t know if I could be happy if no one was interested in me. |

|

Therapist: |

I don’t know either. Is there a way we could find out? |

|

Patient: |

Well, as an experiment, I could not go out on dates for a while and see how I feel. |

|

Therapist: |

I think that’s a good idea. Although it has its flaws, the experimental method is still the best way currently available to discover the facts. You’re fortunate in being able to run this type of experiment. Now, for the first time in your adult life you aren’t attached to a man. If you find you can be happy without a man, this will greatly strengthen you and also make your future relationships all the better. |

|

(Beck et al., 1979, pp. 253– |

|

Over the past several decades, hundreds of studies have shown that Beck’s therapy and similar cognitive and cognitive-

MindTech

Mood Tracking

Cognitive-

But accurately tracking information of this kind is easier said than done. It is hard for people to recall numerous mood changes throughout the day and week. And it is clumsy to keep taking out a diary and write down notes about one’s moods. Fortunately, such difficulties in tracking one’s moods are becoming a thing of the past. Using new texting programs and related smartphone apps—

There are many advantages to recording mood information in these new ways. Because the data is electronically stored and sorted, clients and their therapists can easily track subtle fluctuations and patterns in mood—

One such program, Mood 24/7, texts clients periodically, and the clients reply with numerical scores and accompanying descriptions of how they have been feeling. Its creator compares the process with the daily glucose monitoring successfully used by diabetes patients (Kaplan, 2013).

One of the pioneering mood-

Can you think of other uses, advantages, and disadvantages that might result from the growing use of mood-

Another mood-

It is not yet clear whether these or other such apps will eventually become a staple for the treatment of depression. But it is already clear that if used selectively and carefully, such tools are able to provide a level of detail and accuracy that clinical practitioners of the past could only dream about. ![]()

BETWEEN THE LINES

Popular Search

|

19 |

Percentage of Internet health care searches that seek information on “depression” |

|

14 |

Percentage of Internet health care searches that seek information on “bipolar disorders” |

|

(Fu et al., 2010; harris poll, 2007, 2004) |

|

It is worth noting that a growing number of today’s cognitive-

Sociocultural Approaches

As you read in Chapter 7, sociocultural theorists trace the causes of unipolar depression to the broader social structure in which people live and the roles they are required to play. Two groups of sociocultural treatments are now widely applied in cases of unipolar depression—

Multicultural TreatmentsIn Chapter 3, you read that culture-

Do you think culture-

In the treatment of unipolar depression, culture-

It also appears that the medication needs of many depressed minority clients, especially those who are poor, are inadequately addressed. As you will see later in this chapter, for example, minority clients are less likely than white American clients to receive the most helpful antidepressant medications.

Family-

INTERPERSONAL PSYCHOTHERAPYDeveloped by clinical researchers Gerald Klerman and Myrna Weissman, interpersonal psychotherapy (IPT) holds that any of four interpersonal problem areas may lead to depression and must be addressed: interpersonal loss, interpersonal role dispute, interpersonal role transition, and interpersonal deficits (Bleiberg & Markowitz, 2014; Verdeli, 2014). Over the course of around 16 sessions, IPT therapists address these areas.

interpersonal psychotherapy (IPT) A treatment for unipolar depression that is based on the belief that clarifying and changing one’s interpersonal problems helps lead to recovery.

interpersonal psychotherapy (IPT) A treatment for unipolar depression that is based on the belief that clarifying and changing one’s interpersonal problems helps lead to recovery.

First, depressed people may, as psychodynamic theorists suggest, be having a grief reaction over an important interpersonal loss, the loss of a loved one. In such cases, IPT therapists encourage clients to explore their relationship with the lost person and express any feelings of anger they may discover. Eventually clients develop new ways of remembering the lost person and also look for new relationships.

Second, depressed people may find themselves in the midst of an interpersonal role dispute. Role disputes occur when two people have different expectations of their relationship and of the role each should play. IPT therapists help clients examine whatever role disputes they may be involved in and then develop ways of resolving them.

Depressed people may also be going through an interpersonal role transition, brought about by major life changes such as divorce or the birth of a child. They may feel overwhelmed by the role changes that accompany the life change. In such cases, IPT therapists help them develop the social supports and skills the new roles require.

Finally, some depressed people display interpersonal deficits, such as extreme shyness or social awkwardness, that prevent them from having intimate relationships. IPT therapists may help such clients recognize their deficits and teach them social skills and assertiveness in order to improve their social effectiveness. In the following discussion, the therapist encourages a depressed man to recognize the effect his behavior has on others:

|

Client: |

(After a long pause with eyes downcast, a sad facial expression, and slumped posture) People always make fun of me. I guess I’m just the type of guy who really was meant to be a loner, damn it. (Deep sigh) |

|

Therapist: |

Could you do that again for me? |

|

Client: |

What? |

|

Therapist: |

The sigh, only a bit deeper. |

|

Client: |

Why? (Pause) Okay, but I don’t see what … okay. (Client sighs again and smiles) |

|

Therapist: |

Well, that time you smiled, but mostly when you sigh and look so sad I get the feeling that I better leave you alone in your misery, that I should walk on eggshells and not get too chummy or I might hurt you even more. |

|

Client: |

(A bit of anger in his voice) Well, excuse me! I was only trying to tell you how I felt. |

|

Therapist: |

I know you felt miserable, but I also got the message that you wanted to keep me at a distance, that I had no way to reach you. |

|

Client: |

(Slowly) I feel like a loner, I feel that even you don’t care about me— |

|

Therapist: |

I wonder if other folks need to pass this test, too? |

|

(Beier & Young, 1984, p. 270) |

|

Studies suggest that IPT and related interpersonal treatments for depression have a success rate similar to that of cognitive and cognitive-

COUPLE THERAPYAs you have read, depression can result from marital discord, and recovery from depression is often slower for people who do not receive support from their spouse (Whisman & Beach, 2012; Whisman & Schonbrun, 2010). In fact, as many as half of all depressed clients may be in a dysfunctional relationship. Thus it is not surprising that many cases of depression have been treated by couple therapy, the approach in which a therapist works with two people who share a long-

couple therapy A therapy format in which the therapist works with two people who share a long-

couple therapy A therapy format in which the therapist works with two people who share a long-

Therapists who offer integrative behavioral couples therapy teach specific communication and problem-

Biological Approaches

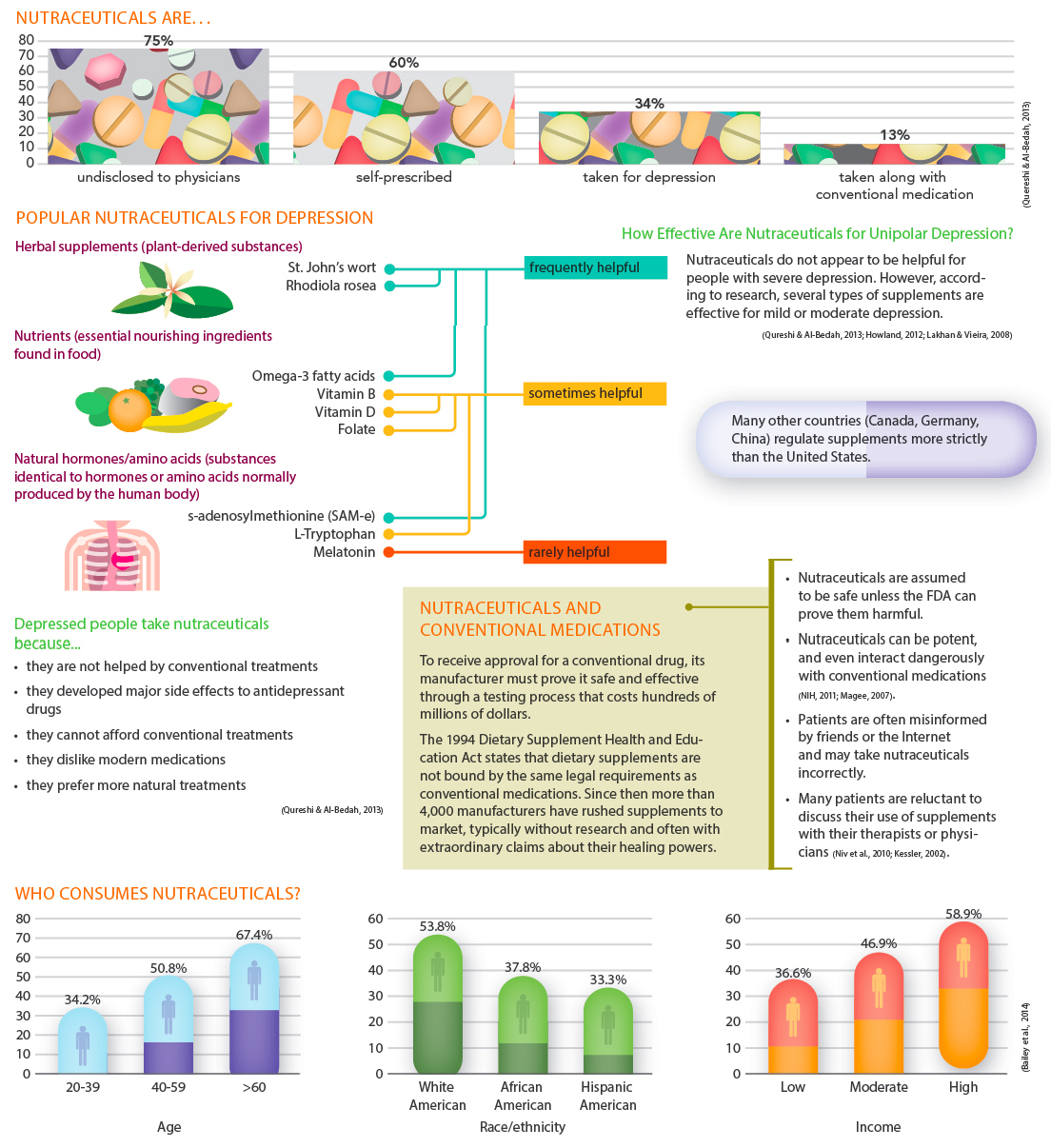

Like several of the psychological and sociocultural therapies, biological treatments can bring significant relief to people with unipolar depression. Usually biological treatment means antidepressant drugs or popular herbal supplements (see InfoCentral below), but for severely depressed people who do not respond to other forms of treatment, it sometimes means electroconvulsive therapy, an approach that has been around for more than 70 years, or brain stimulation, a relatively new group of approaches.

Electroconvulsive TherapyOne of the most controversial forms of treatment for depression is electroconvulsive therapy (ECT). Clinicians and patients alike vary greatly in their opinions of this procedure. Some consider it a safe biological approach with minimal risks; others believe it to be an extreme measure that can cause troublesome memory loss and even neurological damage. Despite the heat of this controversy, ECT is used frequently, largely because it is an effective and fast-

electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) A treatment for depression in which electrodes attached to a patient’s head send an electrical current through the brain, causing a convulsion.

electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) A treatment for depression in which electrodes attached to a patient’s head send an electrical current through the brain, causing a convulsion.

THE TREATMENT PROCEDUREIn an ECT procedure, two electrodes are attached to the patient’s head, and 65 to 140 volts of electricity are passed through the brain for half a second or less. This results in a brain seizure that lasts from 25 seconds to a few minutes. After 6 to 12 such treatments, spaced over 2 to 4 weeks, most patients feel less depressed (Fink, 2014, 2007, 2001). In bilateral ECT, one electrode is applied to each side of the forehead, and a current passes through both sides of the brain. In unilateral ECT, the electrodes are placed so that the current passes through only one side.

THE ORIGINS OF ECTThe discovery that electric shock can be therapeutic was made by accident. In the 1930s, clinical researchers mistakenly came to believe that brain seizures, or the convulsions (severe body spasms) that accompany them, could cure schizophrenia and other psychotic disorders. They observed that people with psychosis rarely suffered from epilepsy (brain seizure disorder) and that people with epilepsy rarely were psychotic, and so concluded that brain seizures or convulsions somehow prevented psychosis. We now know that the observed correlation between seizures and lack of psychotic symptoms does not necessarily imply that one causes the other. Nevertheless, swayed by faulty logic, clinicians in the 1930s searched for ways to induce seizures as a treatment for patients with psychosis.

InfoCentral

DIETARY SUPPLEMENTS: AN ALTERNATIVE TREATMENT

Dietary supplements, also known as nutraceuticals, are nonpharmaceutical and nonfood substances that people may take to supplement their diets, often to help prevent or treat psychological or physical ailments. Depression is the psychological problem for which nutraceuticals are used most often.

A Hungarian physician named Joseph von Meduna gave the drug metrazol to patients suffering from psychosis, and a Viennese physician named Manfred Sakel gave them large doses of insulin (insulin coma therapy). These procedures produced the desired brain seizures, but each was quite dangerous and sometimes even caused death. Finally, an Italian psychiatrist named Ugo Cerletti discovered that he could produce seizures more safely by applying electric currents to a patient’s head, and he and his colleague Lucio Bini soon developed ECT as a treatment for psychosis (Cerletti & Bini, 1938). As you might expect, much uncertainty and confusion accompanied their first clinical application of ECT. Did experimenters have the right to impose such an untested treatment against a patient’s will?

The schizophrenic arrived by train from Milan without a ticket or any means of identification. Physically healthy, he was bedraggled and alternately was mute or expressed himself in incomprehensible gibberish made up of odd neologisms. The patient was brought in but despite their vast animal experience there was great apprehension and fear that the patient might be damaged, and so the shock was cautiously set at 70 volts for one-

(Brandon, 1981, pp. 8-

BETWEEN THE LINES

Source of Inspiration

Prior to developing ECT, Ugo Cerletti visited a slaughterhouse. He observed that before slaughtering hogs with a knife, butchers clamped the animals’ heads with metallic tongs and applied an electric current. The hogs fell unconscious and had convulsions, but they did not die from the current itself. Said Cerletti: “At this point I felt we could venture to experiment on man.”

ECT soon became popular and was tried out on a wide range of psychological problems, as new techniques so often are. Its effectiveness with severe depression in particular became apparent. Ironically, however, doubts were soon raised concerning its usefulness for psychosis, and many researchers have since judged it ineffective for psychotic disorders, except for cases that also include severe depressive symptoms (Freudenreich & Goff, 2011; Taube-

CHANGES IN ECT PROCEDURESAlthough Cerletti gained international fame for his procedure, eventually he abandoned ECT and spent his later years seeking other treatments for mental disorders (Karon, 1985). The reason: he abhorred the broken bones and dislocations of the jaw or shoulders that sometimes resulted from ECT’s severe convulsions, as well as the memory loss, confusion, and brain damage that the seizures could cause. Other clinicians have stayed with the procedure, however, and have changed it over the years to reduce its undesirable consequences. Today’s practitioners give patients strong muscle relaxants to minimize convulsions, thus eliminating the danger of fractures or dislocations. They also use anesthetics (barbiturates) to put patients to sleep during the procedure, reducing their terror. With these precautions, ECT is medically more complex than it used to be, but also less dangerous and somewhat less disturbing (Lihua et al., 2014; Pfeiffer et al., 2011).

Patients who receive ECT, particularly bilateral ECT, typically have difficulty remembering some events, most often events that took place immediately before and after their treatments (Merkl et al., 2011). In most cases, this memory loss clears up within a few months, but some patients are left with gaps in more distant memory, and this form of amnesia can be permanent (Hanna et al., 2009; Wang, 2007; Squire, 1977). Understandably, these patients may become embittered about the procedure.

EFFECTIVENESS OF ECTECT is clearly effective in treating unipolar depression. Studies find that between 60 and 80 percent of ECT patients improve (Perugi et al., 2011; Loo, 2010). The approach is particularly effective when patients follow up the initial cluster of sessions with continuation therapy—either ongoing antidepressant medications or periodic ECT sessions (Fink et al., 2014). The procedure seems to be particularly effective in severe cases of depression that include delusions (Rothschild, 2010). It has been difficult, however, to determine why ECT works so well (Baldinger et al., 2014; Cassidy et al., 2010). After all, this procedure delivers a broad insult to the brain that activates a number of brain areas, causes neurons all over the brain to fire, and leads to the release of all kinds of neurotransmitters, and it affects many other systems throughout the body as well.

Although ECT is effective and ECT techniques have improved, its use has generally declined since the 1950s. Two reasons for this decline are the memory loss caused by ECT and the frightening nature of the procedure (Fink, Kellner, & McCall, 2014). Another is the emergence of effective antidepressant drugs.

Antidepressant DrugsTwo kinds of drugs discovered in the 1950s reduce the symptoms of depression: monoamine oxidase (MAO) inhibitors and tricyclics. These drugs have now been joined by a third group, the so-

| Class/Generic Name | Trade Name |

|---|---|

| Monoamine oxidase inhibitors | |

| Isocarboxazid | Marplan |

| Phenelzine | Nardil |

| Tranylcypromine | Parnate |

| Selegiline | Eldepryl |

| Tricyclics | |

| Imipramine | Tofranil |

| Amitriptyline | Elavil |

| Doxepin | Sinequan; Silenor |

| Trimipramine | Surmontil |

| Desipramine | Norpramin |

| Nortriptyline | Aventil; Pamelor |

| Protriptyline | Vivactil |

| Clomipramine | Anafranil |

| Second- |

|

| Vilazodone | Viibryd |

| Maprotiline | Ludiomil |

| Amoxapine | Asendin |

| Trazodone | Desyrel |

| Fluoxetine | Prozac |

| Sertraline | Zoloft |

| Paroxetine | Paxil |

| Venlafaxine | Effexor |

| Fluvoxamine | Luvox |

| Nefazodone | Serzone |

| Bupropion | Wellbutrin, Aplenzin |

| Mirtazapine | Remeron |

| Citalopram | Celexa |

| Escitalopram | Lexapro |

| Duloxetine | Cymbalta |

| Viloxazine | Vivalan |

| Desvenlafaxine | Pristiq |

| (Information from: Advokat, et al., 2014) | |

MAO INHIBITORSThe effectiveness of MAO inhibitors as a treatment for unipolar depression was discovered accidentally. Physicians noted that iproniazid, a drug being tested on patients with tuberculosis, had an interesting effect: it seemed to make the patients happier (Sandler, 1990). It was found to have the same effect on depressed patients (Kline, 1958; Loomer, Saunders, & Kline, 1957). What this and several related drugs had in common biochemically was that they slowed the body’s production of the enzyme monoamine oxidase (MAO). Thus they were called MAO inhibitors.

MAO inhibitor An antidepressant drug that prevents the action of the enzyme monoamine oxidase.

MAO inhibitor An antidepressant drug that prevents the action of the enzyme monoamine oxidase.

Normally, brain supplies of the enzyme MAO break down, or degrade, the neurotransmitter norepinephrine. MAO inhibitors block MAO from carrying out this activity and thereby stop the destruction of norepinephrine. The result is a rise in norepinephrine activity and, in turn, a reduction of depressive symptoms. Approximately half of depressed patients who take MAO inhibitors are helped by them (Ciraulo, Shader, & Greenblatt, 2011; Thase, Trivedi, & Rush, 1995). There is, however, a potential danger with regard to these drugs. When people who take MAO inhibitors eat foods containing the chemical tyramine—including such common foods as cheeses, bananas, and certain wines—

TRICYCLICSThe discovery of tricyclics in the 1950s was also accidental. Researchers who were looking for a new drug to combat schizophrenia ran some tests on a drug called imipramine (Kuhn, 1958). They discovered that imipramine was of no help in cases of schizophrenia, but it did relieve unipolar depression in many people. The new drug (trade name Tofranil) and related ones became known as tricyclic antidepressants because they all share a three-

tricyclic An antidepressant drug such as imipramine that has three rings in its molecular structure.

tricyclic An antidepressant drug such as imipramine that has three rings in its molecular structure.

In hundreds of studies, depressed patients taking tricyclics have improved much more than similar patients taking placebos, although the drugs must be taken for at least 10 days before such improvements take hold (Advokat et al., 2014). About 65 percent of patients who take tricyclics are helped by them (FDA, 2014).

If depressed people stop taking tricyclics immediately after obtaining relief, they run a high risk of relapsing within a year. If, however, they continue taking the drugs for five months or more after being free of depressive symptoms—

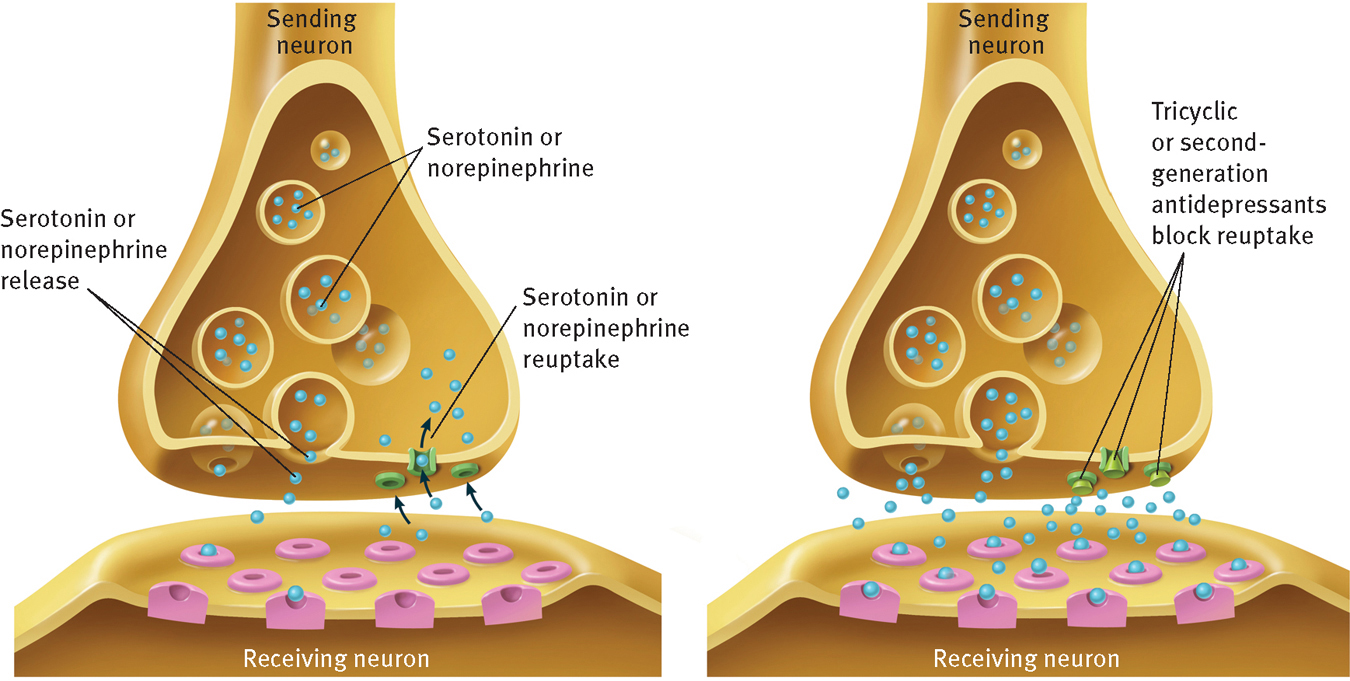

Most researchers have concluded that tricyclics reduce depression by acting on neurotransmitter “reuptake” mechanisms (Ciraulo et al., 2011). Remember from Chapter 3 that messages are carried from the “sending” neuron across the synaptic space to a receiving neuron by a neurotransmitter, a chemical released from the axon ending of the sending neuron. However, there is a complication in this process. While the sending neuron releases the neurotransmitter, a pumplike mechanism in the neuron’s ending immediately starts to reabsorb it in a process called reuptake. The purpose of this reuptake process is to control how long the neurotransmitter remains in the synaptic space and to prevent it from overstimulating the receiving neuron. Unfortunately, reuptake does not always progress properly. The reuptake mechanism may be too efficient in some people—

Reuptake and anti depressants

(Left) Soon after a neuron releases neurotransmitters such as norepinephrine or serotonin into its synaptic space, it activates a pumplike reuptake mechanism to reabsorb excess neurotransmitters. In depression, however, this reuptake process is too active, removing too many neuro trans mitters before they can bind to a receiving neuron. (Right) Tricyclic and most second-

If tricyclics act immediately to increase norepinephrine and serotonin activity, why do the symptoms of depression continue for 10 or more days after drug therapy begins? Growing evidence suggests that when tricyclics are ingested, they initially slow down the activity of the neurons that use norepinephrine and serotonin (Ciraulo et al., 2011; Lambert & Kinsley, 2010). Granted, the reuptake mechanisms of these cells are immediately corrected, thus allowing more efficient transmission of the neurotransmitters, but the neurons themselves respond to the change by releasing smaller amounts of the neurotransmitters. After a week or two, the neurons finally adapt to the tricyclic drugs and go back to releasing normal amounts of the neurotransmitters. Now the corrections in the reuptake mechanisms begin to have the desired effect: the neurotransmitters reach the receiving neurons in greater numbers, hence triggering more neural firing and producing a decrease in depression.

If antidepressant drugs are effective, why do many people seek out herbal supplements, such as Saint-

Soon after tricyclics were discovered, they started being prescribed more often than MAO inhibitors. Tricyclics did not require dietary restrictions as MAO inhibitors did, and people taking them typically showed higher rates of improvement than those taking MAO inhibitors. On the other hand, some people respond better to MAO inhibitors than to either tricyclics or the new antidepressants described next, and such people continue to be given MAO inhibitors (Advokat et al., 2014; Thase, 2006).

SECOND-

selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) A group of second-

selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) A group of second-

In effectiveness and speed of action, the second-

PsychWatch

First Dibs on Antidepressant Drugs?

In our society, the likelihood of being treated for depression and the types of treatment received by clients often differ greatly from ethnic group to ethnic group. In revealing studies, researchers have examined the antidepressant prescriptions written for depressed people, particularly Medicaid recipients with depression (Kirby et al., 2010; Stagnitti, 2005; Strothers et al., 2005; Melfi et al., 2000). The following patterns have emerged:

Almost 40 percent of depressed Medicaid recipients are seen by mental health providers irrespective of gender, race, or ethnic group.

White Americans are twice as likely as Hispanic Americans and more than five times as likely as African Americans to be prescribed antidepressant medications during the early stages of treatment.

Although African Americans are less likely to receive antidepressant drugs, some (but not all) clinical trials suggest that they may be more likely than white Americans to respond to proper antidepressant medications.

African Americans and Hispanic Americans also receive fewer prescriptions than white Americans for most nonpsychiatric disorders.

Among those individuals prescribed antidepressant drugs, African Americans are significantly more likely than white Americans to receive older antidepressant drugs, while white Americans are more likely than African Americans to receive newly marketed second-

generation antidepressant drugs. The older drugs tend to be less expensive for insurance providers.

People who have been helped by the antidepressants readily sing their praises. Consider, for example, the following comments, offered in a recent survey of antidepressant users:

“Going on Prozac was literally going from black and white to color.”

“The psychiatrist put me on an SSRI. And it really helped. Within a couple weeks I felt like I was me again, and I hadn’t been me for a long time.”

“[Zoloft] helps me not feel despair. I guess that’s kind of vague, but when despair actually feels tangible, then there’s nothing vague about it.”

“Within a few weeks [of starting Prozac], I felt a really big difference. You know, life was still filled with problems. But suddenly it was just, they were problems, not this overbearing force.”

“I started taking [Lexapro], and within a week, I felt like a human being again. I could feel something changing inside of me. I could feel this different kind of light, this support, this capability that I didn’t have before. It was very supportive. It was kind of like someone was holding my hand the entire time.”

(Sharpe, 2012)

As popular as the antidepressants are, it is important to recognize that they do not work for everyone. In fact, as you have read, even the most successful of them fails to help at least 35 percent of clients with depression. In fact, some recent reviews have raised the possibility that the failure rate is higher still, especially for people with mild or modest levels of depression (Hegerl et al., 2012; Isacsson & Alder, 2012). How are clients who do not respond to antidepressant drugs treated currently? Researchers have noted that, all too often, their psychiatrists or family physicians simply prescribe alternative antidepressants or antidepressant mixtures—

[S]he spoke, in a wistful manner, of how she wished her treatment could have been different. “I do wonder what might have happened if [at age 16] I could have just talked to someone, and they could have helped me learn about what I could do on my own to be a healthy person. I never had a role model for that. They could have helped me with my eating problems, and my diet and exercise, and helped me learn how to take care of myself. Instead, it was you have this problem with your neurotransmitters, and so here, take this pill Zoloft, and when that didn’t work, it was take this pill Prozac, and when that didn’t work, it was take this pill Effexor, and then when I started having trouble sleeping, it was take this sleeping pill,” she says, her voice sounding more wistful than ever. “I am so tired of the pills.”

(Whitaker, 2010)

Brain StimulationIn recent years, three additional biological approaches have been developed for the treatment of depressive disorders—

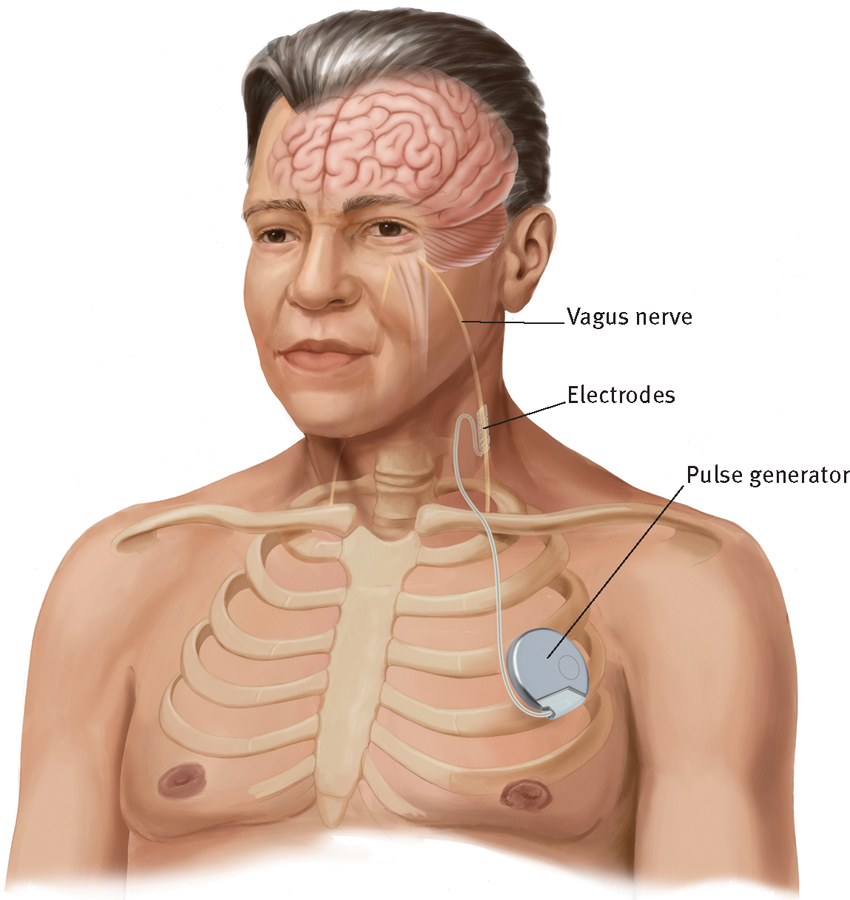

VAGUS NERVE STIMULATIONThe vagus nerve, the longest nerve in the human body, runs from the brain stem through the neck down the chest and on to the abdomen, serving as a primary channel of communication between the brain and major organs such as the heart, lungs, and intestines.

A number of years ago, a group of depression researchers surmised that they might be able to stimulate the brain by electrically stimulating the vagus nerve. They were hoping to mimic the positive effects of ECT without producing the undesired effects or trauma associated with ECT. Their efforts gave birth to a new treatment for depression—

vagus nerve stimulation A treatment procedure for depression in which an implanted pulse generator sends regular electrical signals to a person’s vagus nerve; the nerve then stimulates the brain.

vagus nerve stimulation A treatment procedure for depression in which an implanted pulse generator sends regular electrical signals to a person’s vagus nerve; the nerve then stimulates the brain.

In this procedure, a surgeon implants a small device called a pulse generator under the skin of the chest. The surgeon then guides a wire, which extends from the pulse generator, up to the neck and attaches it to the vagus nerve (see Figure 8-4). Electrical signals travel from the pulse generator through the wire to the vagus nerve. The stimulated vagus nerve then delivers electrical signals to the brain. The pulse generator, which runs on battery power, is typically programmed to stimulate the vagus nerve (and, in turn, the brain) every five minutes for a period of 30 seconds.

Vagus nerve stimulation

In the procedure called vagus nerve stimulation, an implanted pulse generator sends electrical signals to the vagus nerve, which then delivers electrical signals to the brain. This stimulation of the brain helps reduce depression in many patients.

In 2005, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved vagus nerve stimulation for long-

As with ECT, researchers do not yet know precisely why vagus nerve stimulation reduces depression. After all, like ECT, the procedure activates neurotransmitters and areas all over the brain. This includes, but is not limited to, serotonin and norepinephrine and the brain areas that have been implicated in depression (Kosel et al., 2011).

TRANSCRANIAL MAGNETIC STIMULATIONTranscranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) is another technique that is being used to try to stimulate the brain without subjecting depressed patients to the undesired effects or trauma of ECT. In this procedure, first developed in 1985, the clinician places an electromagnetic coil on or above the patient’s head. The coil sends a current into the prefrontal cortex. As you’ll remember from the previous chapter, at least some parts of the prefrontal cortex of depressed people are underactive; TMS appears to increase neuron activity in those regions.

transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) A treatment procedure for depression in which an electromagnetic coil, which is placed on or above a patient’s head, sends a current into the individual’s brain.

transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) A treatment procedure for depression in which an electromagnetic coil, which is placed on or above a patient’s head, sends a current into the individual’s brain.

TMS has been tested by researchers on a range of disorders, including depression. A number of studies have found that the procedure reduces depression when it is administered daily for two to four weeks (Fitzgerald & Daskalakis, 2012; Fox et al., 2012; Rosenberg et al., 2011). Moreover, according to a few investigations, TMS may be just as helpful as ECT when it is administered to severely depressed people who have been unresponsive to other forms of treatment (Mantovani et al., 2012; Rasmussen, 2011). In 2008, TMS was approved by the FDA as a treatment for major depressive disorder.

DEEP BRAIN STIMULATIONAs you read in the previous chapter, researchers have recently linked depression to high activity in Brodmann Area 25, a brain area located just below the cingulate cortex, and some suspect that this area may be a kind of “depression switch.” This finding led neurologist Helen Mayberg and her colleagues (2005) to administer an experimental treatment called deep brain stimulation (DBS) to six severely depressed patients who had previously been unresponsive to all other forms of treatment, including electroconvulsive therapy.

deep brain stimulation (DBS) A treatment procedure for depression in which a pacemaker powers electrodes that have been implanted in Brodmann Area 25, thus stimulating that brain area.

deep brain stimulation (DBS) A treatment procedure for depression in which a pacemaker powers electrodes that have been implanted in Brodmann Area 25, thus stimulating that brain area.

Mayberg’s approach was modeled after deep brain stimulation techniques that had been used successfully in cases of brain seizure disorder and Parkinson’s disease, both of which are related to overly active brain areas. For depression, the Mayberg team drilled two tiny holes into the patient’s skull and implanted electrodes in Area 25. The electrodes were connected to a battery, or “pacemaker,” that was implanted in the patient’s chest (for men) or stomach (for women). The pacemaker powered the electrodes, sending a steady stream of low-

In the initial study of DBS, four of the six severely depressed patients became almost depression-

Understandably, all of this has produced considerable enthusiasm in the clinical field. Nevertheless, it is important to recognize that research on DBS is in its earliest stages. Investigators have yet to run properly controlled studies of the procedure using larger numbers of research participants, to determine its long-

How Do the Treatments for Unipolar Depression Compare?

For most kinds of psychological disorders, no more than one or two treatments or combinations of treatments, if any, emerge as highly successful. Unipolar depression seems to be an exception. One of the most treatable of all abnormal patterns, it may respond to any of several approaches. During the past 20 years, researchers have conducted a number of treatment outcome studies, which have revealed some important trends:

Cognitive, cognitive-

behavioral, interpersonal, and biological therapies are all highly effective treatments for unipolar depression, from mild to severe (Mrazek et al., 2014; Hollon & Ponniah, 2010; Rehm, 2010). In most head- to- head comparisons, they seem to be equally effective at reducing depressive symptoms; however, there are indications that some populations of depressed patients respond better to one therapy than to another. In a pioneering 6-

year study of this issue, experimenters separated 239 moderately and severely depressed people into four treatment groups (Elkin, 1994; Elkin et al., 1989, 1985). One group was treated with 16 weeks of Beck’s cognitive therapy, another with 16 weeks of interpersonal psychotherapy, and a third with the tricyclic drug imipramine. The fourth group received a placebo. A total of 28 therapists conducted these treatments. Using a depression assessment instrument called the Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression, the investigators found that each of the three therapies almost completely eliminated depressive symptoms in 50 to 60 percent of the participants who completed treatment. Only 29 percent of those who received the placebo showed such improvement. This trend also held, although somewhat less powerfully, when other assessment measures were used. These findings are consistent with those of most other comparative outcome studies.

Page 273The study found that drug therapy reduced depressive symptoms more quickly than the cognitive and interpersonal therapies did, but these psychotherapies had matched the drugs in effectiveness by the final 4 weeks of treatment. In addition, more recent studies suggest that cognitive and cognitive-

behavioral therapy may be more effective than drug therapy at preventing recurrences of depression except when drug therapy is continued for an extended period of time (Hollon & Ponniah, 2010). Despite the comparable or even superior showing of cognitive and cognitive- behavioral therapies, in the past few decades there has been a significant increase in the number of prescriptions written for antidepressants: from 2.5 million in 1980 to 4.7 million in 1990 to 254 million today (NIMH, 2011; Horwitz & Wakefield, 2007; Koerner, 2007).  Is laughter the best medicine? A man laughs during a 2013 session of laughter therapy in a public plaza in Caracas, Venezuela. He is one of many who attended this open session of laughter therapy, a relatively new group treatment being offered around the world, based on the belief that laughing at least 15 minutes each day drives away depression and other ills.

Is laughter the best medicine? A man laughs during a 2013 session of laughter therapy in a public plaza in Caracas, Venezuela. He is one of many who attended this open session of laughter therapy, a relatively new group treatment being offered around the world, based on the belief that laughing at least 15 minutes each day drives away depression and other ills.Although the cognitive, cognitive-

behavioral, and interpersonal therapies may lower the likelihood of relapse, they are hardly relapse- proof. Some studies suggest that as many as 30 percent of the depressed patients who respond to these approaches may, in fact, relapse within a few years after the completion of treatment. In an effort to head off relapse, some of today’s cognitive, cognitive- behavioral, and interpersonal therapists continue to offer treatment, perhaps on a less frequent basis and sometimes in group or classroom formats, after the depression lifts— an approach similar to the “continuation” or “maintenance” approaches used with ECT and antidepressant drugs. Early indications are that treatment extensions of this kind do in fact reduce the rate of relapse among successfully treated patients (Bockting, Spinhoven, & Huibers, 2010; Hollon & Ponniah, 2010). In fact, some research suggests that people who have recovered from depression are less likely to relapse if they receive continuation or maintenance therapy in either drug or psychotherapy form, irrespective of which kind of therapy they originally received (Flynn & Himle, 2011). When people with unipolar depression have significant discord in their marital relationships, couple therapy tends to be as helpful as cognitive, cognitive-

behavioral, interpersonal, or drug therapy (Lebow et al., 2012, 2010; Whisman & Schonbrun, 2010). In head-

to- head comparisons, depressed people who receive strictly behavioral therapy have shown less improvement than those who receive cognitive, cognitive- behavioral, interpersonal, or biological therapy. Behavioral therapy has, however, proved more effective than placebo treatments or no attention at all (Hollon & Ponniah, 2010; Farmer & Chapman, 2008). Also, as you have seen, behavioral therapy is of less help to people who are severely depressed than to those with mild or moderate depression. BETWEEN THE LINES

Dropping a Name

One study found that 55 percent of people who posed as patients with a few depressive symptoms were given prescriptions for the antidepressant Paxil when they told their doctor that they had seen it advertised, compared with only 10 percent of pseudopatients who did not mention an ad (Kravitz et al., 2005).

Most studies suggest that traditional—

long- term— psychodynamic therapies are less effective than these other therapies in treating all levels of unipolar depression (Hollon & Ponniah, 2010; Svartberg & Stiles, 1991). Many psychodynamic clinicians argue, however, that this system of therapy simply does not lend itself to empirical research, and its effectiveness should be judged more by therapists’ reports of individual recovery and progress (Busch et al., 2004). Page 274Studies have found that a combination of psychotherapy (usually cognitive, cognitive-

behavioral, or interpersonal) and drug therapy is modestly more helpful to depressed people than either treatment alone (Ballas et al., 2010; Rehm, 2010). As you will see in Chapter 17, these various trends do not always carry over to the treatment of depressed children and adolescents. For example, a broad 6-

year project called the Treatment for Adolescents with Depression Study (TADS) indicates that a combination of cognitive and drug therapy may be much more helpful to depressed teenagers than either treatment alone (NIMH, 2010; TADS, 2007). Among biological treatments, ECT appears to be somewhat more effective than antidepressant drugs for reducing depression. ECT also acts more quickly. Half of patients treated by either intervention, however, relapse within a year unless the initial treatment is followed up by continuing drug treatment or by psychotherapy (Fink, 2014, 2007, 2001; Trevino et al., 2010). In addition, the new brain stimulation treatments seem helpful for some severely depressed people who have been repeatedly unresponsive to drug therapy, ECT, or psychotherapy.

When clinicians today choose a biological treatment for mild to severe unipolar depression, they most often prescribe one of the antidepressant drugs. In some cases, clients may actually request specific ones based on recommendations from friends or on ads they have seen (see PsychWatch below). Clinicians are not likely to refer patients for ECT unless the depression is severe and has been unresponsive to drug therapy and psychotherapy (Kellner et al., 2012). ECT appears to be helpful for 50 to 80 percent of the severely depressed patients who do not respond to other interventions (Perugi et al., 2011; APA, 1993). If a depressed person seems to be at high risk for suicide, the person’s clinician sometimes makes the referral for ECT treatment more readily (Fink et al., 2014; Kobeissi et al., 2011; Fink, 2007, 2001). Although ECT clearly has a beneficial effect on suicidal behavior in the short run, studies do not clearly indicate that it has a long-

term effect on suicide rates.

PsychWatch

“Ask Your Doctor If This Medication Is Right for You”

“Maybe you are suffering from depression.” “Ask your doctor about Cymbalta.” “There is no need to suffer any longer.” Anyone who watches television or surfs the Internet is familiar with phrases such as these. They are at the heart of direct-

Antidepressants are among the leading drugs to receive DTC television advertising, along with oral antihistamines, cholesterol reducers, and anti-

How did we get here? Where did this tidal wave of advertising come from? And what’s with those endless “side effects” that are recited so rapidly at the end of each and every commercial? It’s a long story, but here are some of the key plot twists that helped set the stage for the emergence of DTC television drug advertising.

1938: Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act

Congress passed the Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act, which gave the FDA jurisdiction over the labels on prescriptions and over-

1962: Kefauver-

In the spirit of consumer protection, Congress passed a law requiring that all pharmaceutical drugs be proved safe and effective. The law also transferred still more authority for prescription drug ads from the Federal Trade Commission (which regulates most other kinds of advertising) to the FDA (Wilkes et al., 2000). Perhaps most important, the law set up rules that companies were required to follow in their drug advertisements, including a detailed summary of the drug’s contraindications, side effects, and effectiveness, and a “fair balance” coverage of risks and benefits.

1962–

For the next two decades, pharmaceutical companies targeted their ads to the physicians who were writing the prescriptions. As more and more psychotropic drugs were developed, psychiatrists were included among those targeted.

1981: First Pitch

The pharmaceutical drug industry proposed shifting the advertising of drugs directly to consumers. The argument was based on the notion that such advertising would protect consumers by directly educating them about those drugs that were available.

1983: First DTC Drug Ad

The first direct-

1985: Lifting the Ban

The FDA lifted the moratorium and allowed DTC drug ads as long as the ads adhered to the physician-

1997: FDA Makes Television-

Recognizing that its previous guidelines could not readily be applied to brief TV ads, which may run for only 30 seconds, the FDA changed its guidelines for DTC television drug ads. It ruled that DTC television advertisements must simply mention a drug’s important risks and must indicate where consumers can get further information about the drug—

2004: FDA relaxes some DTC regulations

In 2004, the FDA eliminated the requirement that drug manufacturers must reprint entire prescription information in their ads. Instead a “simplified brief summary” of prescribing practices is sufficient.

Today

Currently, most of the DTC advertising continues to appear on traditional offline media such as television, radio, newspapers, and magazines. There are some DTC ads on digital outlets such as product Web sites and in social media; however, online efforts by pharmaceutical companies are unfolding slowly, largely because FDA guidelines for online DTC advertising are relatively unclear (Ventola, 2011; Donohue et al., 2007). In 2009, the FDA wrote a revision of its DTC regulations, but the revision remains in draft form.