9.1 What Is Suicide?

Not every self-

suicide A self-

suicide A self-

Intentioned deaths may take various forms. Consider the following examples. All three of these people intended to die, but their motives, concerns, and actions differed greatly:

Dave was a successful man. By the age of 50 he had risen to the vice presidency of a small but profitable investment firm. He had a caring wife and two teenage sons who respected him. They lived in an upper-

In August of his fiftieth year, everything changed. Dave was fired. Just like that. The economy had gone bad once again, the firm’s profits were down, and the president wanted to try new, fresher investment strategies and marketing approaches. Dave had been “old school.” He didn’t fully understand today’s investors—

The experience of failure, loss, and emptiness was overwhelming for Dave. He looked for another position, but found only low-

Six months after losing his job, Dave began to consider ending his life. The pain was too great, the humiliation unending. He hated the present and dreaded the future. Throughout February he went back and forth. On some days he was sure he wanted to die. On other days, an enjoyable evening or uplifting conversation might change his mind temporarily. On a Monday late in February he heard about a job possibility, and the anticipation of the next day’s interview seemed to lift his spirits. But Tuesday’s interview did not go well. He knew there’d be no job offer. He went home, took a recently purchased gun from his locked desk drawer, and shot himself.

BETWEEN THE LINES

Shocking Comparison

Each year, more deaths in the United States result from suicide (38,364) than from motor vehicle crashes (33,687) (CDC, 2013).

Demaine never truly recovered from his mother’s death. He was only seven years old and unprepared for such a loss. His father sent him to live with his grandparents for a time, to a new school with new kids and a new way of life. In Demaine’s mind, all these changes were for the worse. He missed the joy and laughter of the past. He missed his home, his father, and his friends. Most of all he missed his mother.

He did not really understand her death. His father said that she was in heaven now, at peace, happy. Demaine’s unhappiness and loneliness continued day after day and he began to put things together in his own way. He believed he would be happy again if he could join his mother. He felt she was waiting for him, waiting for him to come to her. The thoughts seemed so right to him; they brought him comfort and hope. One evening, shortly after saying good night to his grandparents, Demaine climbed out of bed, went up the stairs to the roof of their apartment house, and jumped to his death. In his mind he was joining his mother in heaven.

BETWEEN THE LINES

Additional Punishment

Up through the nineteenth century, the bodies of suicide victims in France and England were sometimes dragged through the streets on a frame, head downward, the way criminals were dragged to their executions.

By the early nineteenth century, most legal punishments for people who committed suicide (for example, confiscating their estates) were abolished across Europe and America.

In the United States, the last prosecution for attempted suicide occurred in 1961; the prosecution was not successful.

(Wertheimer, 2001; Fay, 1995)

Tya and Noah had met on a speed date. On a lark, Tya and a friend had registered at the speed date event, figuring, “What’s the worst thing that can happen?” On the night of the big event, Tya talked to dozens of guys, none of whom appealed to her—

It was Tya’s first serious relationship; it became her whole life. Thus she was truly shocked and devastated when, on the one-

As the weeks went by, Tya was filled with two competing feelings—

Tya’s friends became more and more worried about her. At first they sympathized with her pain, assuming it would soon lift. But as time went on, her depression and anger worsened, and Tya began to act strangely. Always a bit of a drinker, she started to drink heavily and to mix her drinks with various kinds of drugs.

One night Tya went into her bathroom, reached for a bottle of sleeping pills, and swallowed a handful of them. She wanted to make her pain go away, and she wanted Noah to know just how much pain he had caused her. She continued swallowing pill after pill, crying and swearing as she gulped them down. When she began to feel drowsy, she decided to call her close friend Dedra. She was not sure why she was calling, perhaps to say good-

While Tya seemed to have mixed feelings about her death, Dave was clear in his wish to die. Whereas Demaine viewed death as a trip to heaven, Dave saw it as an end to his existence. Such differences can be important in efforts to understand and treat suicidal persons. Accordingly, Shneidman distinguished four kinds of people who intentionally end their lives: the death seeker, death initiator, death ignorer, and death darer.

How should clinicians decide whether to hospitalize a person who is considering suicide or even one who has made an attempt?

Death seekers clearly intend to end their lives at the time they attempt suicide. This singleness of purpose may last only a short time. It can change to confusion the very next hour or day, and then return again in short order. Dave, the middle-

death seeker A person who clearly intends to end his or her life at the time of a suicide attempt.

death seeker A person who clearly intends to end his or her life at the time of a suicide attempt.

Death initiators also clearly intend to end their lives, but they act out of a belief that the process of death is already under way and that they are simply hastening the process. Some expect that they will die in a matter of days or weeks. Many suicides among the elderly and very sick fall into this category. Robust novelist Ernest Hemingway was profoundly concerned about his failing body as he approached his sixty-

death initiator A person who attempts suicide believing that the process of death is already under way and that he or she is simply hastening the process.

death initiator A person who attempts suicide believing that the process of death is already under way and that he or she is simply hastening the process.

Death ignorers do not believe that their self-

death ignorer A person who attempts suicide without recognizing the finality of death.

death ignorer A person who attempts suicide without recognizing the finality of death.

Death darers experience mixed feelings, or ambivalence, about their intent to die, even at the moment of their attempt, and they show this ambivalence in the act itself. Although to some degree they wish to die, and they often do die, their risk-

death darer A person who is ambivalent about the wish to die even as he or she attempts suicide.

death darer A person who is ambivalent about the wish to die even as he or she attempts suicide.

When people play indirect, covert, partial, or unconscious roles in their own deaths, Shneidman (2001, 1993, 1981) classified them in a suicide-

subintentional death A death in which the victim plays an indirect, hidden, partial, or unconscious role.

subintentional death A death in which the victim plays an indirect, hidden, partial, or unconscious role.

In recent years, another behavioral pattern, self-

Self-

How Is Suicide Studied?

Suicide researchers face a major obstacle: the people they study are no longer alive. How can investigators draw accurate conclusions about the intentions, feelings, and circumstances of those who can no longer explain their actions? Two research methods attempt to deal with this problem, each with only partial success.

One strategy is retrospective analysis, a kind of psychological autopsy in which clinicians and researchers piece together data from the suicide victim’s past (Schwartz, 2011; Wetzel & Murphy, 2005). Relatives, friends, therapists, or physicians may remember past statements, conversations, and behaviors that shed light on a suicide. Retrospective information may also be provided by the suicide notes that some victims leave behind (Wong et al., 2009).

retrospective analysis A psychological autopsy in which clinicians piece together information about a person’s suicide from the person’s past.

retrospective analysis A psychological autopsy in which clinicians piece together information about a person’s suicide from the person’s past.

However, such sources of information are not always available or reliable. Around half of all suicide victims have never been in psychotherapy (Stolberg et al., 2002), and less than one-

Because of these limitations, many researchers also use a second strategy—

MediaSpeak

Videos of Self-

By Roni Caryn Rabin, The New York Times

YouTube videos are spreading word of a self-

As many as one in five young men and women are believed to have engaged at least once in what psychologists call nonsuicidal self-

Some of the videos weave text, music and photography together, which may glamorize self-

And the videos are popular. Many viewers rated the videos positively, selecting them as favorites more than 12,000 times, according to the new study, … whose authors reviewed the 100 most-

Why do you think certain individuals decide to display their acts of self-

Stephen P. Lewis, assistant professor of psychology at the University of Guelph in Ontario and the paper’s lead author, calls the YouTube depictions of self-

“The risk is that these videos normalize self-

Only about one in four of the 100 most-

About a quarter of the videos conveyed a mixed message about self-

February 22, 2011 “VITAL SIGNS; Behavior: Videos of Self-

Patterns and Statistics

Suicide happens within a larger social setting, and researchers have gathered many statistics regarding the social contexts in which such deaths take place. They have found, for example, that suicide rates vary from country to country (Kirkcaldy et al., 2010). South Korea, Russia, Hungary, Germany, Austria, Finland, Denmark, China, and Japan have very high rates—

Religious affiliation and beliefs may help account for these national differences (Foo et al., 2014). For example, countries that are largely Catholic, Jewish, or Muslim tend to have low suicide rates. Perhaps in these countries, strict prohibitions against suicide or a strong religious tradition deter many people from committing suicide (Stack & Kposowa, 2008). Yet there are exceptions to this tentative rule. Austria, a largely Roman Catholic country, has one of the highest suicide rates in the world.

What factors besides religious affiliation and beliefs might help account for national variations in suicide rates?

Research is beginning to suggest that religious doctrine may not help prevent suicide as much as the degree of an individual’s devoutness. Regardless of their particular persuasion, very religious people seem less likely to commit suicide (Cook, 2014; Güngörmüş, Tanriverdi, & Gündoğan, 2014; Stack & Kposowa, 2008). Similarly, it seems that people who have a greater reverence for life are less prone to consider or attempt self-

BETWEEN THE LINES

Deal Breaker

If clients state an intention to commit suicide, therapists may break the doctor–

The suicide rates of men and women also differ. Three times as many women attempt suicide as men, yet men succeed at more than four times the rate of women (AFSP, 2014; CDC, 2013). Around the world 19 of every 100,000 men kill themselves each year; the suicide rate for women is 4 per 100,000 (Levi et al., 2003).

Although various explanations have been proposed for this gender difference (Fiori et al., 2011), a popular one points to the different methods used by men and women (Stack & Wasserman, 2009). Men tend to use more violent methods, such as shooting, stabbing, or hanging themselves, whereas women use less violent methods, such as drug overdose. Guns are used in 56 percent of the male suicides in the United States, compared with 31 percent of the female suicides (CDC, 2014).

Suicide is also related to social environment and marital status (You, Van Orden, & Conner, 2011). In one study, around half of the individuals who had committed suicide were found to have no close personal friends (Maris, 2001), although they may be active on Internet and social networks. Fewer still had close relationships with parents and other family members. In a related vein, research has revealed that divorced persons have a higher suicide rate than married or cohabitating individuals (Roskar et al., 2011; Stolberg et al., 2002).

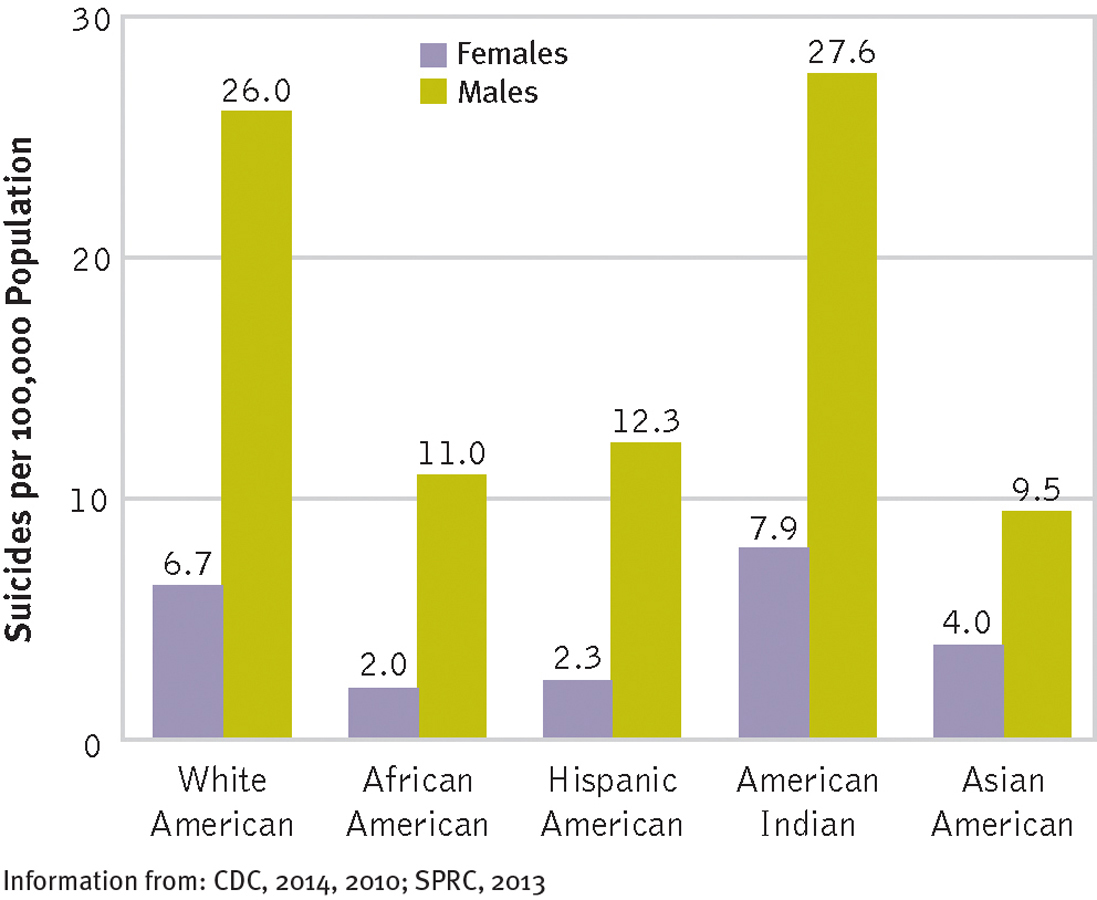

Finally, in the United States at least, suicide rates seem to vary according to race (see Figure 9-1). The overall suicide rate of white Americans is more than twice as high as that of African Americans, Hispanic Americans, and Asian Americans (AFSP, 2014; CDC, 2013). A major exception to this pattern is the very high suicide rate of American Indians, which is at least 20 percent higher than that of white Americans (Herne et al., 2014; SPRC, 2013; CDC, 2010). Although the extreme poverty of many American Indians may partly explain their high suicide rate, studies show that factors such as alcohol use, modeling, and the availability of guns may also play a role (Lanier, 2010). In addition to differences across racial groups, researchers have found that suicide rates sometimes differ within groups. Among Hispanic Americans, for example, Puerto Ricans are significantly more likely to attempt suicide than any other Hispanic American group (Baca-

Suicide, race, and gender

In the United States, American Indians have the highest suicide rates among both males and females.

Some of these statistics on suicide have been questioned. Analyses suggest, for example, that the actual rate of suicide may be 15 percent higher for African Americans and 6 percent higher for women than usually reported (Barnes, 2010; Phillips & Ruth, 1993). People in these groups are more likely than others to use methods of suicide that can be mistaken for causes of accidental death, such as poisoning, drug overdose, single-