1.5 What Do Clinical Researchers Do?

Research is the key to accuracy in all fields of study; it is particularly important in abnormal psychology because a wrong belief in this field can lead to great suffering. At the same time, clinical researchers, also called clinical scientists, face certain challenges that make their work very difficult. They must, for example, figure out how to measure such elusive concepts as private thoughts, mood changes, and human potential. They must consider the different cultural backgrounds, races, and genders of the people they choose to study. And they must always ensure that the rights of their research participants, both human and animal, are not violated. Let us examine the leading methods used by today’s researchers.

scientific method The process of systematically gathering and evaluating information through careful observations to understand a phenomenon.

Clinical researchers try to discover broad laws, or principles, of abnormal psychological functioning. They search for a general, or nomothetic, understanding of the nature, causes, and treatments of abnormality. They do not typically assess, diagnose, or treat individual clients; that is the job of clinical practitioners. To gain a broad insight, clinical researchers, like scientists in other fields, use the scientific method—that is, they collect and evaluate information through careful observations. These observations in turn enable them to pinpoint and explain relationships between variables.

Simply stated, a variable is any characteristic or event that can vary, whether from time to time, from place to place, or from person to person. Age, sex, and race are human variables. So are eye color, occupation, and social status. Clinical researchers are interested in variables such as childhood upsets, present life experiences, moods, social functioning, and responses to treatment. They try to determine whether two or more such variables change together and whether a change in one variable causes a change in another. Will the death of a parent cause a child to become depressed? If so, will a given treatment reduce that depression?

hypothesis A hunch or prediction that certain variables are related in certain ways.

Such questions cannot be answered by logic alone because scientists, like all human beings, frequently make errors in thinking. Thus, clinical researchers must depend mainly on three methods of investigation: the case study, which typically is focused on one individual, and the correlational method and experimental method, approaches that are usually used to gather information about many individuals. Each is best suited to certain kinds of circumstances and questions. As a group, these methods enable scientists to form and test hypotheses, or hunches, that certain variables are related in certain ways—

The Case Study

case study A detailed account of a person’s life and psychological problems.

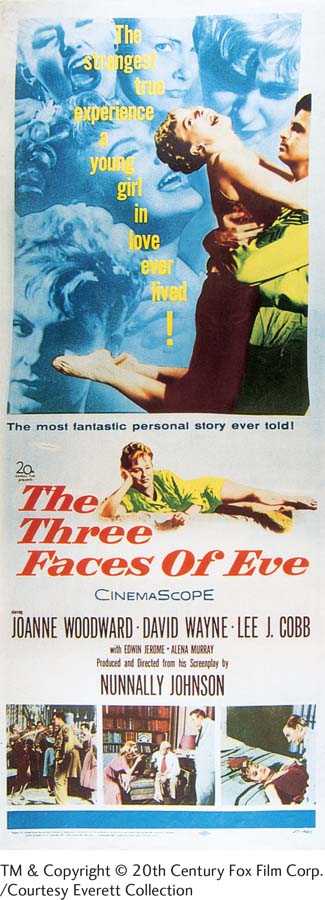

A case study is a detailed description of a person’s life and psychological problems. It describes the person’s history, present circumstances, and symptoms. It may also include speculation about why the problems developed, and it may describe the person’s treatment (Yin, 2013). As you will see in Chapter 5, one of the field’s best-

Most clinicians take notes and keep records in the course of treating their patients, and some further organize such notes into a formal case study to be shared with other professionals. The clues offered by a case study may help a clinician better understand or treat the person under discussion (Yin, 2013). In addition, case studies may play nomothetic roles that go far beyond the individual clinical case.

How Are Case Studies Helpful? Case studies can be a source of new ideas about behavior and “open the way for discoveries” (Bolgar, 1965). Freud’s theory of psychoanalysis was based mainly on the patients he saw in private practice. In addition, a case study may offer tentative support for a theory. Freud used case studies in this way as well, regarding them as evidence for the accuracy of his ideas. Conversely, case studies may serve to challenge a theory’s assumptions (Yin, 2013).

Case studies may also show the value of new therapeutic techniques. And finally, case studies may offer opportunities to study unusual problems that do not occur often enough to permit a large number of observations (Goodwin & Goodwin, 2012). Investigators of problems such as personality disorder once relied entirely on case studies for information.

What Are the Limitations of Case Studies? Case studies also have limitations (Yin, 2013). First, they are reported by biased observers, that is, by therapists who have a personal stake in seeing their treatments succeed. These therapists must choose what to include in a case study, and their choices may at times be self-

Why do case studies and other anecdotal offerings influence people so much, often more than systematic research does?

The limitations of the case study are largely addressed by two other methods of investigation: the correlational method and the experimental method. These methods do not offer the rich details that make case studies so interesting, but they do help investigators draw broad conclusions about abnormality in the population at large. Thus they are now the preferred methods of clinical investigation.

Three features of the correlational and experimental methods enable clinical investigators to gain general insights: (1) The researchers typically observe many individuals (see MindTech below). (2) The researchers apply procedures uniformly and can thus repeat, or replicate, their investigations. And (3) the researchers use statistical tests to analyze the results of a study.

The Correlational Method

correlation The degree to which events or characteristics vary along with each other.

correlational method A research procedure used to determine how much events or characteristics vary along with each other.

Correlation is the degree to which events or characteristics vary with each other. The correlational method is a research procedure used to determine this “co-

To test this question, researchers have collected life stress scores (for example, the number of threatening events experienced during a certain period of time) and depression scores (for example, scores on a depression survey) from individuals and have correlated these scores. The people who are chosen for a study are its subjects, or participants, the term preferred by today’s investigators. Typically, investigators have found that life stress and depression variables do indeed increase or decrease together (Monroe et al., 2014). That is, the greater someone’s life stress score, the higher his or her score on the depression scale. When variables change the same way, their correlation is said to have a positive direction and is referred to as a positive correlation. Alternatively, correlations can have a negative rather than a positive direction. In a negative correlation, the value of one variable increases as the value of the other variable decreases. Researchers have found, for example, a negative correlation between depression and activity level. The greater one’s depression, the lower the number of one’s activities.

MindTech

A Researcher’s Paradise?

A Researcher’s Paradise?

Two of the biggest problems for researchers are finding enough participants for their studies and obtaining a sufficient range of participants. Until recent years, undergraduates were the most common participants in behavioral research—

On the downside, undergraduates are a pretty homogeneous group whose behaviors and emotions do not always generalize to other groups in society (Phillips, 2011). Thus, it is probably good that the face of research recruitment is now changing. More and more researchers are turning to social networking sites—

One recent study demonstrates the power and potential of social media participant pools (Kosinski et al., 2013). In this investigation, 58,000 Facebook subscribers allowed the researchers access to their list of “likes,” and the subscribers further filled out online personality tests. The study found that information about a participant’s likes could predict with considerable accuracy his or her personality traits, level of happiness, use of addictive substances, and level of intelligence, among other variables. Similarly, other social media site studies have tested various psychological theories “about relationships, identity, self-

What a great resource, right? Not so fast. The studies above asked social media users whether they were willing to participate, but in a number of other studies, the users do not know that their posted information is being examined and tested. Inasmuch as posted information is publicly available, some researchers believe it is ethical to study that information without informing users that they are indeed being studied.

Facebook and most other social media sites do not have policies prohibiting scholars from studying user profiles without permission (Rosenbloom, 2007). In contrast, many research institutes have concluded that postings on social networking sites should be considered private, and they require their researchers at their institutions to obtain explicit permission from social media users when network information is being examined. While this technology-

BETWEEN THE LINES

People Who Purchased This Participant Also Purchased …

Leave it to Amazon. More and more researchers are now finding study participants on Amazon Mechanical Turk, an Amazon site that helps investigators and prospective participants find each other. Researchers post their studies on this Internet marketplace, and participants choose which ones to sign up for. Upon completion of the online study, participants receive payment via an Amazon.com gift certificate, and Amazon receives 10 percent of their reimbursement.

There is yet a third possible outcome for a correlational study. The variables under study may be unrelated, meaning that there is no consistent relationship between them. As the measures of one variable increase, those of the other variable sometimes increase and sometimes decrease. Studies have found that depression and intelligence are unrelated, for example.

In addition to knowing the direction of a correlation, researchers need to know its magnitude, or strength. That is, how closely do the two variables correspond? Does one always vary along with the other, or is their relationship less exact? When two variables are found to vary together very closely in person after person, the correlation is said to be high, or strong.

The direction and magnitude of a correlation are often calculated numerically and expressed by a statistical term called the correlation coefficient. The correlation coefficient can vary from +1.00, which indicates a perfect positive correlation between two variables, down to –1.00, which represents a perfect negative correlation. The sign of the coefficient (+ or –) signifies the direction of the correlation; the number represents its magnitude. The closer the correlation is to .00, the weaker, or lower in magnitude, it is. Thus correlations of +.75 and –.75 are of equal magnitude and equally strong, whereas a correlation of +.25 is weaker than either.

Everyone’s behavior is changeable, and many human responses can be measured only approximately. Most correlations found in psychological research, therefore, fall short of perfect positive or negative correlation. For example, one early study of life stress and depression, with a sample of 68 adults, found a correlation of +.53 (Miller, Ingham, & Davidson, 1976). Although hardly perfect, a correlation of this magnitude is considered large in psychological research.

When Can Correlations Be Trusted? Scientists must decide whether the correlation they find in a given sample of participants accurately reflects a real correlation in the general population. Could the observed correlation have occurred by mere chance? They can test their conclusions with a statistical analysis of their data, using principles of probability. In essence, they ask how likely it is that the study’s particular findings have occurred by chance. If the statistical analysis indicates that chance is unlikely to account for the correlation they found, researchers may conclude that their findings reflect a real correlation in the general population.

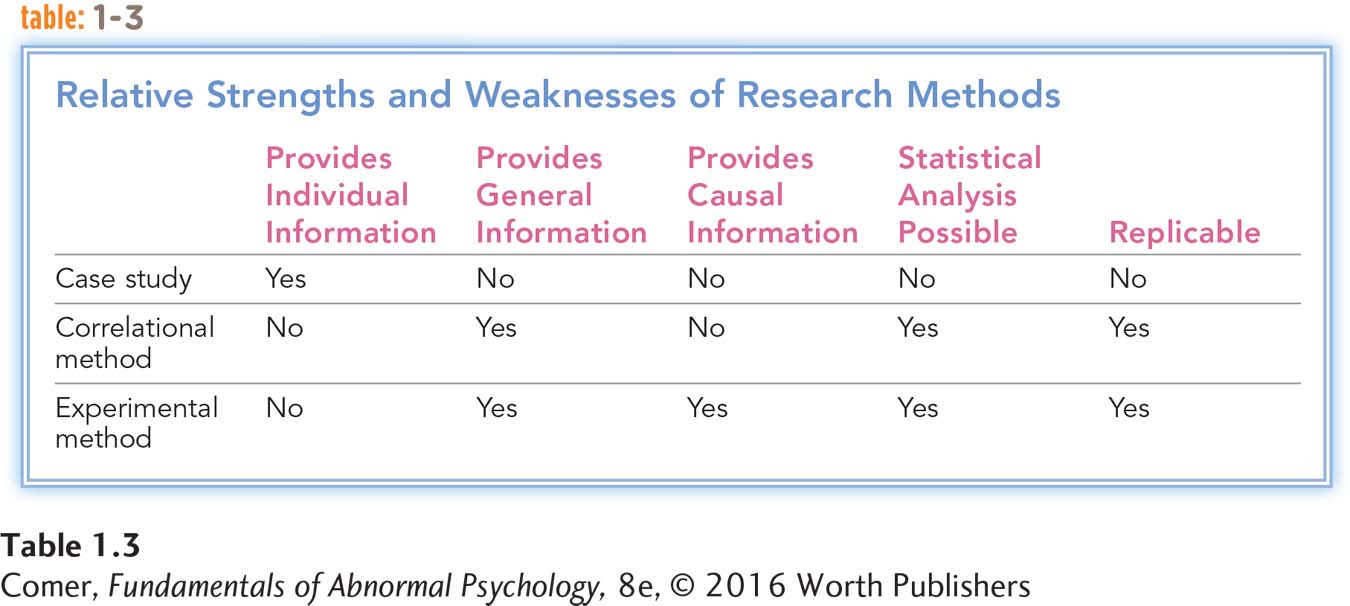

What Are the Merits of the Correlational Method? The correlational method has certain advantages over the case study (see Table 1.3). Because researchers measure their variables, observe many participants, and apply statistical analyses, they are in a better position to generalize their correlations to people beyond the ones they have studied. Furthermore, researchers can easily repeat correlational studies using new samples of participants to check the results of earlier studies.

Can you think of other correlations in life that are interpreted mistakenly as causal?

Although correlations allow researchers to describe the relationship between two variables, they do not explain the relationship (Jackson, 2012). When we look at the positive correlation found in many life stress studies, we may be tempted to conclude that increases in recent life stress cause people to feel more depressed. In fact, however, the two variables may be correlated for any one of three reasons: (1) Life stress may cause depression. (2) Depression may cause people to experience more life stress (for example, a depressive approach to life may cause people to perform poorly at work or may interfere with social relationships). (3) Depression and life stress may each be caused by a third variable, such as financial problems (Gutman & Nemeroff, 2011).

Although correlations say nothing about causation, they can still be of great use to clinicians. Clinicians know, for example, that suicide attempts increase as people become more depressed. Thus, when they work with severely depressed clients, they stay on the lookout for signs of suicidal thinking. Perhaps depression directly causes suicidal behavior, or perhaps a third variable, such as a sense of hopelessness, causes both depression and suicidal thoughts. Whatever the cause, just knowing that there is a correlation may enable clinicians to take measures (such as hospitalization) to help save lives.

epidemiological study A study that measures the incidence and prevalence of a disorder in a given population.

Special Forms of Correlational Research Epidemiological studies and longitudinal studies are two kinds of correlational research used widely by clinical investigators. Epidemiological studies reveal the incidence and prevalence of a disorder in a particular population. Incidence is the number of new cases that emerge during a given period of time. Prevalence is the total number of cases in the population during a given period; prevalence includes both existing and new cases.

Over the past 40 years, clinical researchers throughout the United States have worked on one of the largest epidemiological studies of mental disorders ever conducted, called the Epidemiologic Catchment Area Study (Ramsey et al., 2013). They have interviewed more than 20,000 people in five cities to determine the prevalence of many psychological disorders and the treatment programs used. Two other large-

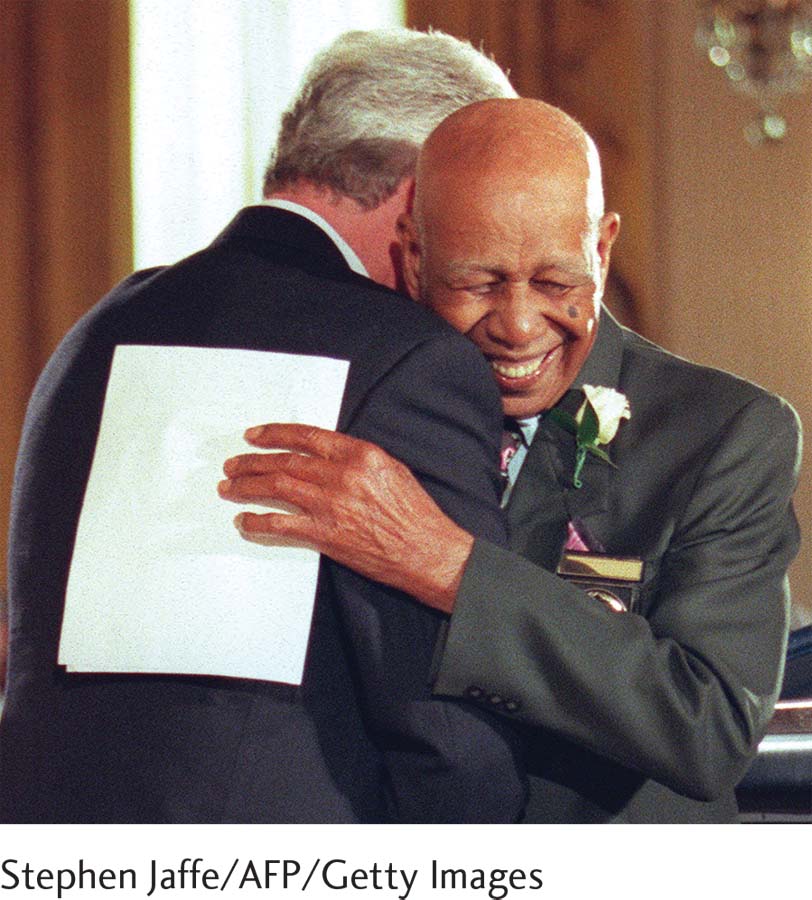

Such epidemiological studies have helped researchers identify groups at risk for particular disorders. Women, it turns out, have a higher rate of anxiety disorders and depression than men, while men have a higher rate of alcoholism than women. Elderly people have a higher rate of suicide than young people. Hispanic Americans experience posttraumatic stress disorder more than other racial and ethnic groups in the United States. And persons in some countries have higher rates of certain mental disorders than those in other countries. Eating disorders such as anorexia nervosa, for example, appear to be more common in Western countries than in non-

longitudinal study A study that observes the same participants on many occasions over a long period of time.

In longitudinal studies, correlational studies of another kind, researchers observe the same individuals on many occasions over a long period of time. In several such studies, investigators have observed the progress over the years of normally functioning children whose mothers or fathers suffered from schizophrenia (Rasic et al., 2014; Mednick, 1971). The researchers have found, among other things, that the children of the parents with the most severe cases of schizophrenia were particularly likely to develop a psychological disorder and to commit crimes at later points in their development.

The Experimental Method

experiment A research procedure in which a variable is manipulated and the effect of the manipulation is observed.

independent variable The variable in an experiment that is manipulated to determine whether it has an effect on another variable.

dependent variable The variable in an experiment expected to change as the independent variable is manipulated.

An experiment is a research procedure in which a variable is manipulated and the manipulation’s effect on another variable is observed. The manipulated variable is called the independent variable and the variable being observed is called the dependent variable.

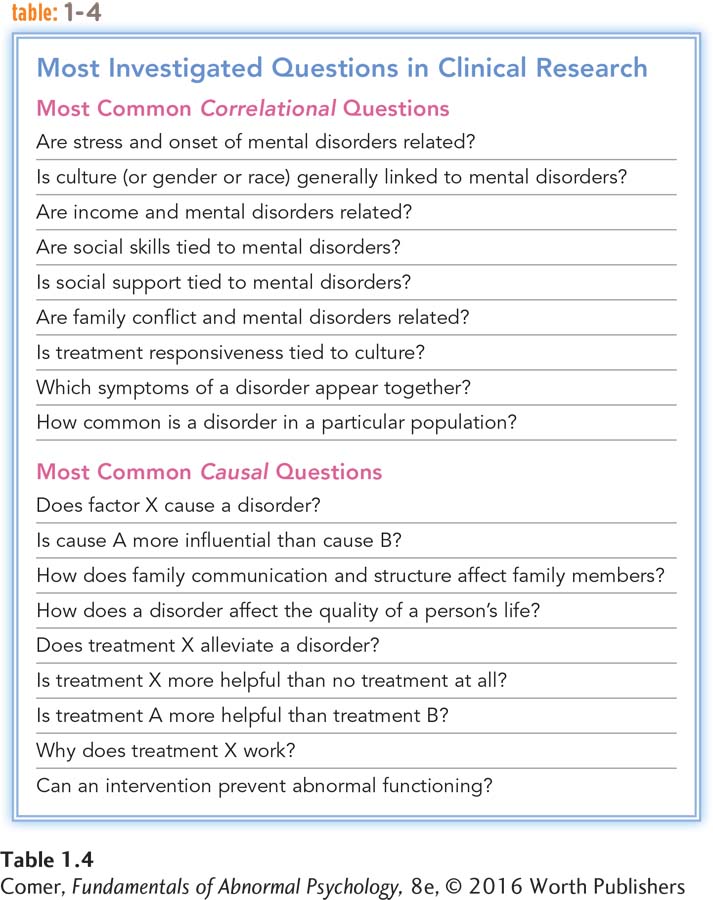

To examine the experimental method more fully, let’s consider a question that is often asked by clinicians (Toth et al., 2014): “Does a particular therapy relieve the symptoms of a particular disorder?” Because this question is about a causal relationship, it can be answered only by an experiment (see Table 1.4). That is, experimenters must give the therapy in question to people who are suffering from a disorder and then observe whether they improve. Here the therapy is the independent variable, and psychological improvement is the dependent variable.

As with correlational studies, investigators who conduct experiments must do a statistical analysis on their data and find out how likely it is that the observed improvement is due to chance. Again, if that likelihood is very low, the improvement is considered to be statistically significant, and the experimenter may conclude with some confidence that it is due to the independent variable.

confound In an experiment, a variable other than the independent variable that is also acting on the dependent variable.

If the true cause of changes in the dependent variable cannot be separated from other possible causes, then an experiment gives very little information. Thus, experimenters must try to eliminate all confounds from their studies—

For example, situational variables, such as the location of the therapy office (say, a quiet country setting) or soothing background music in the office, may have a therapeutic effect on participants in a therapy study. Or perhaps the participants are unusually motivated or have high expectations that the therapy will work, factors that thus account for their improvement. To guard against confounds, researchers should include three important features in their experiments—

control group In an experiment, a group of participants who are not exposed to the independent variable.

The Control Group A control group is a group of research participants who are not exposed to the independent variable under investigation but whose experience is similar to that of the experimental group, the participants who are exposed to the independent variable. By comparing the two groups, an experimenter can better determine the effect of the independent variable.

experimental group In an experiment, the participants who are exposed to the independent variable under investigation.

To study the effectiveness of a particular therapy, for example, experimenters typically divide participants into two groups. The experimental group may come into an office and receive the therapy for an hour, while the control group may simply come into the office for an hour. If the experimenters find later that the people in the experimental group improve more than the people in the control group, they may conclude that the therapy was effective, above and beyond the effects of time, the office setting, and any other confounds. To guard against confounds, experimenters try to provide all participants, both control and experimental, with experiences that are identical in every way—

MediaSpeak

Flawed Study, Gigantic Impact

By David DiSalvo, Forbes, May 19, 2012

In 2001, Dr. Robert L. Spitzer, psychiatrist and professor emeritus of Columbia University, presented a paper at a meeting of the American Psychiatric Association about something called “reparative therapy” [also known as “conversion therapy”] for gay men and women. By undergoing reparative therapy, the paper claimed, gay men and women could change their sexual orientation. Spitzer had interviewed 200 allegedly former-

Spitzer, now 79 years old, was no stranger to the controversy surrounding his chosen subject. Thirty years earlier, he had played a leading role in removing homosexuality from the list of mental disorders in the association’s diagnostic manual [DSM-

Fast forward to 2012, and Spitzer is of quite a different mind. Last month he told a reporter with The American Prospect that he regretted the 2001 study and the effect it had on the gay community, and that he owed the community an apology. And this month he sent a letter to the Archives of Sexual Behavior, which published his work in 2003, asking that the journal retract his paper.

Spitzer’s mission to clean the slate is commendable, but the effects of his work have been coursing through the homosexual community like acid since it made headlines a decade ago. His study was seized upon by anti-

Spitzer didn’t invent reparative therapy, and he isn’t the only researcher to have conducted studies claiming that it works, but as an influential psychiatrist from a prestigious university, his words carried a lot of weight.

In his recantation of the study, he says that it contained at least two fatal flaws: the self reports from those he surveyed were not verifiable, and he didn’t include a control group of men and women who didn’t undergo the therapy for comparison. Self reports are notoriously unreliable…. Lacking a control group is a fundamental no-

The object lesson worth drawing from this story is that just one instance of bad science given the blessing of recognized experts can lead to years of damaging lies that snowball out of control. Spitzer cannot be held solely responsible for what happened after his paper was published, but he’d probably agree now that the study should never have been presented in the first place. At the very least, his example may help prevent future episodes of the same.

May 19, 2012, “How One Flawed Study Spawned a Decade of Lies” by David DiSalvo. From Forbes, 5/19/2012 © 2012 Forbes LLC. All rights reserved. Used by permission and protected by the copyright laws of the United States. The printing, copying, redistribution, or retransmission of this content without express written permission is prohibited.

random assignment A selection procedure that ensures that participants are randomly placed either in the control group or in the experimental group.

Random Assignment Researchers must also watch out for differences in the makeup of the experimental and control groups since those differences may also confound a study’s results. In a therapy study, for example, the experimenter may unintentionally put wealthier participants in the experimental group and poorer ones in the control group. This difference, rather than their therapy, may be the cause of the greater improvement later found among the experimental participants. To reduce the effects of preexisting differences, experimenters typically use random assignment. This is the general term for any selection procedure that ensures that every participant in the experiment is as likely to be placed in one group as the other. Researchers might, for example, assign people to groups by flipping a coin or picking names out of a hat.

Blind Design A final confound problem is bias. Participants may bias an experiment’s results by trying to please or help the experimenter. In a therapy experiment, for example, if those participants who receive the treatment know the purpose of the study and which group they are in, they might actually work harder to feel better or fulfill the experimenter’s expectations. If so, subject, or participant, bias rather than therapy could be causing their improvement.

Why might sugar pills or other kinds of placebo treatments help some people feel better?

blind design An experiment in which participants do not know whether they are in the experimental or the control condition.

To avoid this bias, experimenters can prevent participants from finding out which group they are in. This experimental strategy is called a blind design because the individuals are blind as to their assigned group. In a therapy study, for example, control participants could be given a placebo (Latin for “I shall please”), something that looks or tastes like real therapy but has none of its key ingredients. This “imitation” therapy is called placebo therapy. If the experimental (true therapy) participants improve more than the control (placebo therapy) participants, experimenters have more confidence that the true therapy has caused their improvement.

BETWEEN THE LINES

Animal Research

Approximately 101 million animals are used in biomedical research each year. Fewer than 1 percent of them are dogs, cats, or primates.

(U.S. Department of Agriculture, 2014; Speaking of Research, 2011)

An experiment may also be confounded by experimenter bias—that is, experimenters may have expectations that they unintentionally transmit to the participants in their studies. In a drug therapy study, for example, the experimenter might smile and act confident while providing real medications to the experimental participants but frown and appear hesitant while offering placebo drugs to the control participants. This kind of bias is sometimes referred to as the Rosenthal effect, after the psychologist who first identified it (Rosenthal, 1966). Experimenters can eliminate their own bias by arranging to be blind themselves. In a drug therapy study, for example, an aide could make sure that the real medication and the placebo drug look identical. The experimenter could then administer treatment without knowing which participants were receiving true medications and which were receiving false medications. While either the participants or the experimenter may be kept blind in an experiment, it is best that both be blind—

Alternative Experimental Designs Clinical researchers must often settle for experimental designs that are less than ideal (Manton et al., 2014). The most common such variations are the quasi-

quasi-

In quasi-

natural experiment An experiment in which nature, rather than an experimenter, manipulates an independent variable.

In natural experiments, nature itself manipulates the independent variable, and the experimenter observes the effects. Natural experiments must be used for studying the psychological effects of unusual and unpredictable events, such as floods, earthquakes, plane crashes, and fires. Because the participants in these studies are selected by an accident of fate rather than by the investigators’ design, natural experiments are actually a kind of quasi-

On December 26, 2004, an earthquake occurred beneath the Indian Ocean off the coast of Sumatra, Indonesia. The earthquake triggered a series of massive tsunamis that flooded the ocean’s coastal communities, killed more than 225,000 people, and injured and left millions of survivors homeless, particularly in Indonesia, Sri Lanka, India, and Thailand. Within months of this disaster, researchers conducted natural experiments in which they collected data from hundreds of survivors and from control groups of people who lived in areas not directly affected by the tsunamis. The disaster survivors scored significantly higher on anxiety and depression measures (dependent variables) than the controls did. The survivors also experienced more sleep problems, feelings of detachment, arousal, difficulties concentrating, startle responses, and guilt feelings than the controls did (Musa et al., 2014; Heir et al., 2010). Over the past several years, other natural experiments have focused on survivors of the 2010 Haitian earthquake, the massive earthquake and tsunami in Japan in 2011, the Northeast’s Superstorm Sandy in 2012, and the unprecedented Oklahoma tornados in 2013. These studies have also revealed lingering psychological symptoms among survivors of those disasters (Iwadare et al., 2013).

analogue experiment A research method in which the experimenter produces abnormal-

Experimenters often run analogue experiments. Here they induce laboratory participants to behave in ways that seem to resemble real-

single-

Finally, scientists sometimes do not have the luxury of experimenting on many participants. They may, for example, be investigating a disorder so rare that few participants are available. Experimentation is still possible, however, with a single-

For example, using a particular kind of single-

What Are the Limits of Clinical Investigations?

We began this section by noting that clinical scientists look for general laws that will help them understand, treat, and prevent psychological disorders. As we have seen, however, circumstances can interfere with their progress.

Each method of investigation that we have observed addresses some of the problems involved in studying human behavior, but no one approach overcomes them all. Thus it is best to view each research method as part of a team of approaches that together may shed light on abnormal human functioning. When more than one method has been used to investigate a disorder, it is important to ask whether all the results seem to point in the same direction. If they do, clinical scientists are probably making progress toward understanding and treating that disorder. Conversely, if the various methods seem to produce conflicting results, the scientists must admit that knowledge in that particular area is still limited.

Protecting Human Participants

Human research participants have needs and rights that must be respected. In fact, researchers’ primary obligation is to avoid harming the human participants in their studies—

The vast majority of researchers are conscientious about fulfilling this obligation. They try to conduct studies that test their hypotheses and further scientific knowledge in a safe and respectful way. But there have been some notable exceptions to this over the years, particularly several infamous studies conducted in the mid-

Do outside restrictions on research—

Institutional Review Board (IRB) An ethics committee in a research facility that is empowered to protect the rights and safety of human research participants.

Who, beyond researchers themselves, might directly watch over the rights and safety of human participants? For the past few decades, that responsibility has been given to Institutional Review Boards, or IRBs. Each research facility has an IRB—

It turns out that protecting the rights and safety of human research participants is a complex undertaking. Thus, IRBs often are forced to conduct a kind of risk-

The participants enlist voluntarily.

Before enlisting, the participants are adequately informed about what the study entails (“informed consent”).

The participants can end their participation in the study at any time.

The benefits of the study outweigh its costs/risks.

The participants are protected from physical and psychological harm.

Page 33The participants have access to information about the study.

The participants’ privacy is protected by principles such as confidentiality or anonymity.

Unfortunately, even with IRBs on the job, these rights can be in jeopardy. Consider, for example, the right of informed consent. To help ensure that participants understand what they are getting into when they enlist for a study, IRBs typically require that the individuals read and sign an “informed consent form” that spells out everything they need to know. But how clear are such forms? Not very, according to some investigations (Albala, Doyle, & Appelbaum, 2010; Mathew & McGrath, 2002).

It turns out that most such forms—

In short, the IRB system is flawed, much like the research undertakings it oversees. There are various reasons for this. One is that ethical principles are subtle and elusive notions that do not always translate into simple regulations and guidelines. Another reason is that ethical decisions—

BETWEEN THE LINES

Predictions Made Without Research

“Websites will never replace newspapers.”

Newsweek, 1995

“Next Christmas, the iPod will be dead.”

Amstrad (electronics company), 2005

“Guitar music is on the way out.”

Decca Records Company, 1964

“The cloning of mammals … is biologically impossible.”

James McGrath and Davor Solter, genetic researchers, 1984

“The ‘telephone’ has too many shortcomings to be seriously considered as a means of communication.”

Western Union, 1876

Summing Up

WHAT DO CLINICAL RESEARCHERS DO? Researchers use the scientific method to uncover nomothetic principles of abnormal psychological functioning. They attempt to identify and examine relationships between variables and depend primarily on three methods of investigation: the case study, the correlational method, and the experimental method.

A case study is a detailed account of a person’s life and psychological problems.

Correlational studies are used to systematically observe the degree to which events or characteristics vary together. This method allows researchers to draw broad conclusions about abnormality in the population at large. Two widely used forms of the correlational method are epidemiological studies and longitudinal studies.

In experiments, researchers manipulate suspected causes to see whether expected effects will result. This method allows researchers to determine the causes of various conditions or events. Clinical experimenters must often settle for experimental designs that are less than ideal, including the quasi-

Each research facility has an Institutional Review Board (IRB) that has the power and responsibility to protect the rights and safety of human participants in all studies conducted at that facility. Members of the IRB review each study during the planning stages and can require changes in the proposed study before granting approval for the undertaking. If the required changes are not made, the IRB has the authority to disapprove the study. Among the important participant rights that the IRB protects is the right of informed consent, an acceptable risk/benefit balance, and privacy (confidentiality or anonymity).