Chapter 2 PUTTING IT…together

Integration of the Models

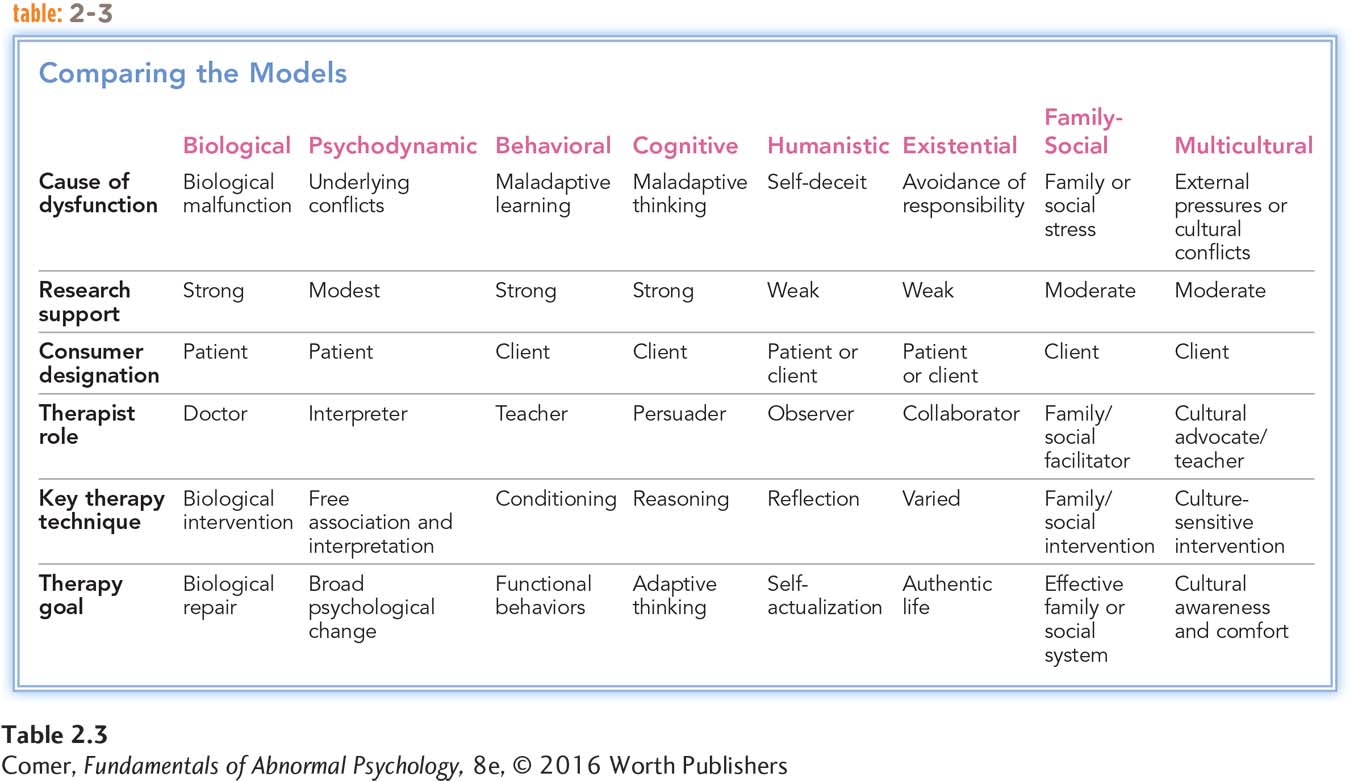

Today’s leading models vary widely (see Table 2.3), and none of the models has proved consistently superior. Each helps us appreciate a key aspect of human functioning, and each has important strengths as well as serious limitations.

BETWEEN THE LINES

In Their Words

“Help! I’m being held prisoner by my heredity and environment.”

Dennis Allen

With all their differences, the conclusions and techniques of the various models are often compatible. Certainly our understanding and treatment of abnormal behavior are more complete if we appreciate the biological, psychological, and sociocultural aspects of a person’s problem rather than only one of them. Not surprisingly, a growing number of clinicians favor explanations of abnormal behavior that consider more than one kind of cause at a time. These explanations, sometimes called biopsychosocial theories, state that abnormality results from the interaction of genetic, biological, developmental, emotional, behavioral, cognitive, social, cultural, and societal influences (Calkins & Dollar, 2014). A case of depression, for example, might best be explained by pointing collectively to an individual’s inheritance of unfavorable genes, traumatic losses during childhood, negative ways of thinking, and social isolation.

Some biopsychosocial theorists favor a diathesis-

In a similar quest for integration, many therapists are now combining treatment techniques from several models (Norcross & Beutler, 2014). In fact, 22 percent of today’s clinical psychologists, 34 percent of counseling psychologists, and 26 percent of social workers describe their approach as “eclectic” or “integrative” (Prochaska & Norcross, 2013). Studies confirm that clinical problems often respond better to combined approaches than to any one therapy alone. For example, as you will see, drug therapy combined with cognitive therapy is sometimes the most effective treatment for depression.

Given the recent rise in biopsychosocial theories and combination treatments, our examinations of abnormal behavior throughout this book will take two directions. As different disorders are presented, we will look at how today’s models explain each disorder, how clinicians who endorse each model treat people with the disorder, and how well these explanations and treatments are supported by research. Just as important, however, we will also be observing how the explanations and treatments may build upon and strengthen one another, and we will examine current efforts toward integration of the models.