3.3 Treatment: How Might the Client Be Helped?

Over the course of 10 months, Franco was treated for depression and related symptoms. He improved considerably during that time, as the following report describes:

During therapy, Franco’s debilitating depression relented. Increasingly, he came to appreciate that his mother’s accusations against him—

Franco also managed to straighten out his problems at work. He explained his recent difficulties to his immediate supervisor at the bank and committed himself to improving his recent performance. His supervisor, with whom he had been friendly before his recent struggles, said she was glad that he was communicating openly and emphasized that he would be given the opportunity to improve his performance. He was surprised to hear how highly he had been regarded over the years, although as she put it, “Why would you have been promoted otherwise?”

Over the course of therapy, Franco also forced himself to spend more time having fun with his friends. He found his mood on the upswing as a result of these reestablished relationships. In addition, he began dating a woman he met through Jesse. He often considered the lessons he learned in treatment, trying to handle this new relationship in ways different from the destructive patterns of his past.

Clearly, treatment helped Franco, and by its conclusion he was a happier, more functional person than the man who had first sought help 10 months earlier. But how did his therapist decide on the treatment program that proved to be so helpful?

Treatment Decisions

BETWEEN THE LINES

Famous Movie Clinicians

Dr. Benjamin (Still Alice, 2014)

Dr. Banks (Side Effects, 2013)

Dr. Patel (Silver Linings Playbook, 2012)

Dr. Cawley (Shutter Island, 2010)

Dr. Steele (Changeling, 2008)

Dr. Rosen (A Beautiful Mind, 2001)

Dr. Crowe (The Sixth Sense, 1999)

Dr. Maguire (Good Will Hunting, 1997)

Dr. Lecter (The Silence of the Lambs, 1991)

Dr. Marvin (What About Bob?, 1991)

Dr. Sayer (Awakenings, 1990)

Dr. Sobel (Analyze This, 1999)

Dr. Berger (Ordinary People, 1980)

Dr. Dysart (Equus, 1977)

Nurse Ratched (One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest, 1975)

Franco’s therapist began, like all therapists, with assessment information and diagnostic decisions. Knowing the specific details and background of Franco’s problem (idiographic data) and combining this individual information with broad information about the nature and treatment of depression, the clinician arrived at a treatment plan for him.

Yet therapists may be influenced by additional factors when they make treatment decisions. Their treatment plans typically reflect their theoretical orientations and how they have learned to conduct therapy (Sharf, 2015). As therapists apply a favored model in case after case, they become more and more familiar with its principles and treatment techniques and tend to use them in work with still other clients.

Current research may also play a role. Most clinicians say that they value research as a guide to practice (Beutler et al., 1995). However, not all of them actually read research articles, so they cannot be directly influenced by them (Rivett, 2011; Stewart & Chambless, 2007). In fact, according to surveys, therapists gather much of their information about the latest developments in the field from colleagues, professional newsletters, workshops, conferences, Web sites, books, and the like (Simon, 2011; Corrie & Callanan, 2001). Unfortunately, the accuracy and usefulness of these sources vary widely.

empirically supported treatment Therapy that has received clear research support for a particular disorder and has corresponding treatment guidelines. Also known as evidence-

To help clinicians become more familiar with and apply research findings, there is an ever-

The Effectiveness of Treatment

Altogether, more than 400 forms of therapy are currently practiced in the clinical field (Wedding & Corsini, 2014). Naturally, the most important question to ask about each of them is whether it does what it is supposed to do. Does a particular treatment really help people overcome their psychological problems? On the surface, the question may seem simple. In fact, it is one of the most difficult questions for clinical researchers to answer.

The first problem is how to define “success.” If, as Franco’s therapist implies, he still has much progress to make at the conclusion of therapy, should his recovery be considered successful? The second problem is how to measure improvement (Hunsley & Lee, 2014; Lambert, 2010). Should researchers give equal weight to the reports of clients, friends, relatives, therapists, and teachers? Should they use rating scales, inventories, therapy insights, observations, or some other measure?

Perhaps the biggest problem in determining the effectiveness of treatment is the variety and complexity of the treatments currently in use. People differ in their problems, personal styles, and motivations for therapy. Therapists differ in skill, experience, orientation, and personality. And therapies differ in theory, format, and setting. Because an individual’s progress is influenced by all these factors and more, the findings of a particular study will not always apply to other clients and therapists.

Proper research procedures address some of these problems. By using control groups, random assignment, matched research participants, and the like, clinicians can draw certain conclusions about various therapies. Even in studies that are well designed, however, the variety and complexity of treatment limit the conclusions that can be reached (Kazdin, 2015, 2013, 2006).

Despite these difficulties, the job of evaluating therapies must be done, and clinical researchers have plowed ahead with it. Investigators have, in fact, conducted thousands of therapy outcome studies, studies that measure the effects of various treatments. The studies typically ask one of three questions: (1) Is therapy in general effective? (2) Are particular therapies generally effective? (3) Are particular therapies effective for particular problems?

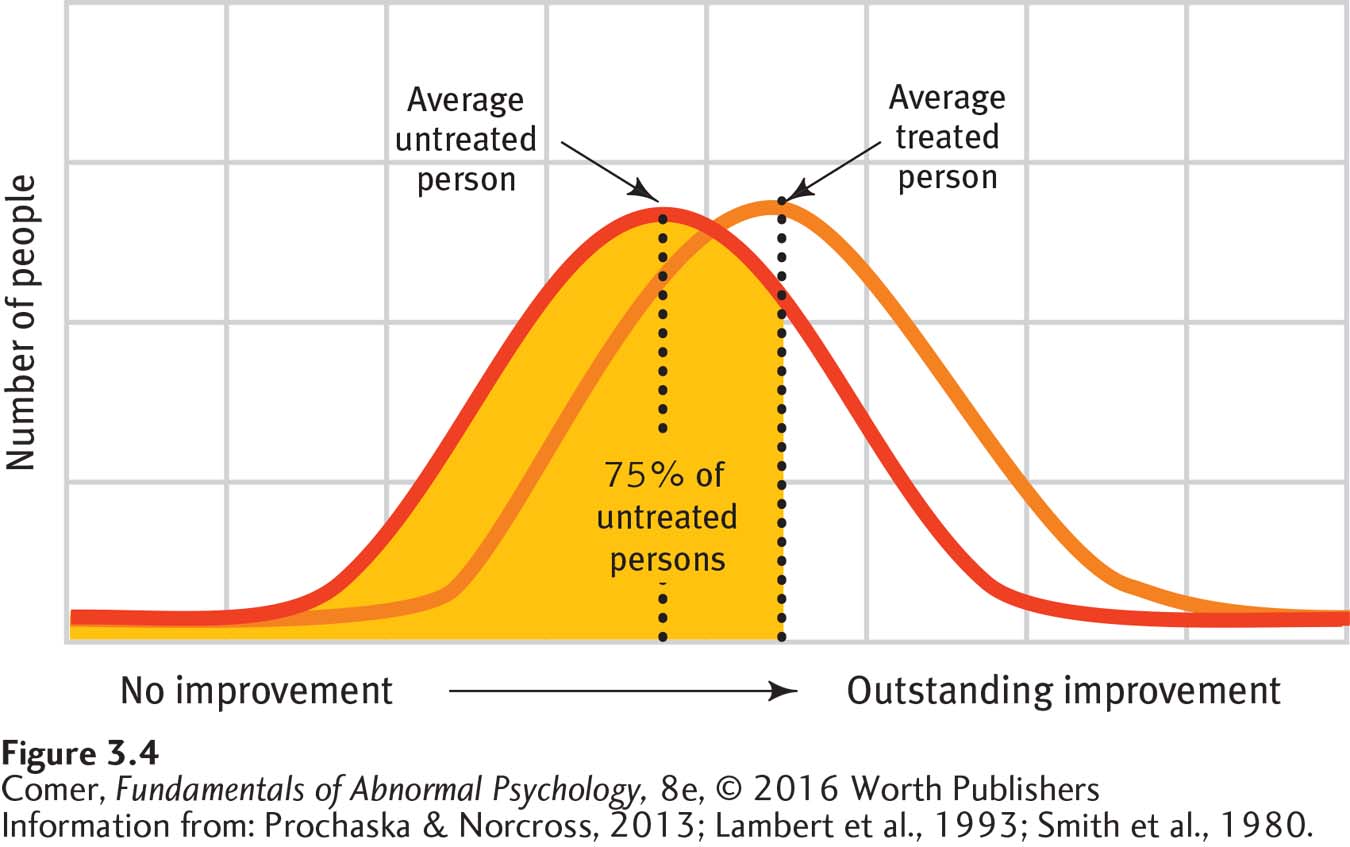

Is Therapy Generally Effective? Studies suggest that therapy often is more helpful than no treatment or than placebos. A pioneering review examined 375 controlled studies, covering a total of almost 25,000 people seen in a wide assortment of therapies (Smith, Glass, & Miller, 1980; Smith & Glass, 1977). The reviewers combined the findings of these studies by using a special statistical technique called meta-

Some clinicians have concerned themselves with an important related question: Can therapy be harmful? A number of studies suggest that 5 to 10 percent of patients actually seem to get worse because of therapy (Lambert, 2010). Their symptoms may become more intense, or they may develop new ones, such as a sense of failure, guilt, reduced self-

Are Particular Therapies Generally Effective? The studies you have read about so far have lumped all therapies together to consider their general effectiveness. Many researchers, however, consider it wrong to treat all therapies alike. Some critics suggest that these studies are operating under a uniformity myth—a false belief that all therapies are equivalent despite differences in the therapists’ training, experience, theoretical orientations, and personalities (Good & Brooks, 2005; Kiesler, 1995, 1966).

Thus, an alternative approach examines the effectiveness of particular therapies. Most research of this kind shows each of the major forms of therapy to be superior to no treatment or to placebo treatment (Prochaska & Norcross, 2013). A number of other studies have compared particular therapies with one another and found that no one form of therapy generally stands out over all others (Luborsky et al., 2006, 2002, 1975).

rapprochement movement A movement to identify a set of common factors, or common strategies, that run through all successful therapies.

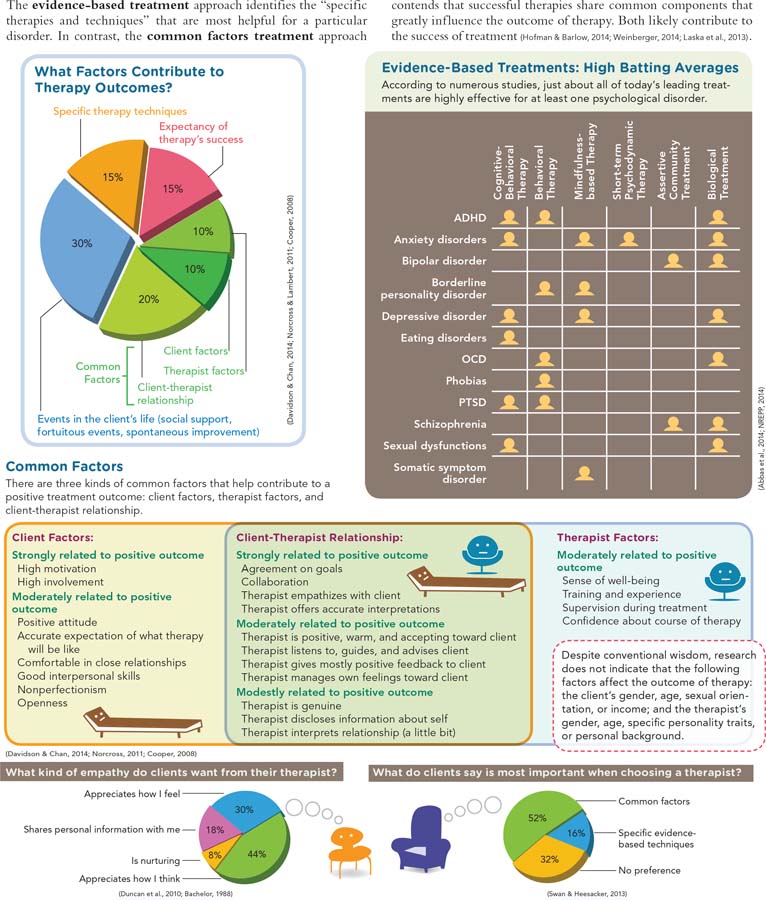

If different kinds of therapy have similar successes, might they have something in common? People in the rapprochement movement have tried to identify a set of common factors, or common strategies, that may run through all effective therapies, regardless of the clinicians’ particular orientations (Sharf, 2015) (see InfoCentral below). Surveys of highly successful therapists suggest, for example, that most give feedback to clients, help clients focus on their own thoughts and behavior, pay attention to the way they and their clients are interacting, and try to promote self-

Are Particular Therapies Effective for Particular Problems? People with different disorders may respond differently to the various forms of therapy (Norcross & Beutler, 2014; Beutler, 2011). In an oft-

BETWEEN THE LINES

Contradictory Trends

Since 1998, the number of patients receiving psychotherapy alone has fallen by 34 percent. The number receiving medication alone has increased by 23 percent.

However, today’s patients express a three times greater preference for psychotherapy over medications (Gaudiano, 2013).

psychopharmacologist A psychiatrist who primarily prescribes medications.

As you read previously, studies also show that some clinical problems may respond better to combined approaches (Norcross & Beutler, 2014; Valencia et al., 2013). Drug therapy is sometimes combined with certain forms of psychotherapy, for example, to treat depression. In fact, it is now common for clients to be seen by two therapists—

Obviously, knowledge of how particular therapies fare with particular disorders can help therapists and clients alike make better decisions about treatment (Holt et al., 2015; Beutler, 2011, 2002, 2000). We will keep returning to this issue as we examine the various disorders throughout the book.

Summing Up

TREATMENT The treatment decisions of therapists may be influenced by assessment information, the diagnosis, the clinician’s theoretical orientation and familiarity with research, and the state of knowledge in the field. Determining the effectiveness of treatment is difficult. Nevertheless, therapy outcome studies have led to three general conclusions: (1) people in therapy are usually better off than people with similar problems who receive no treatment; (2) the various therapies do not appear to differ dramatically in their general effectiveness; and (3) certain therapies or combinations of therapies do appear to be more effective than others for certain disorders. Some therapists currently advocate empirically supported treatment—

InfoCentral

COMMON FACTORS IN THERAPY