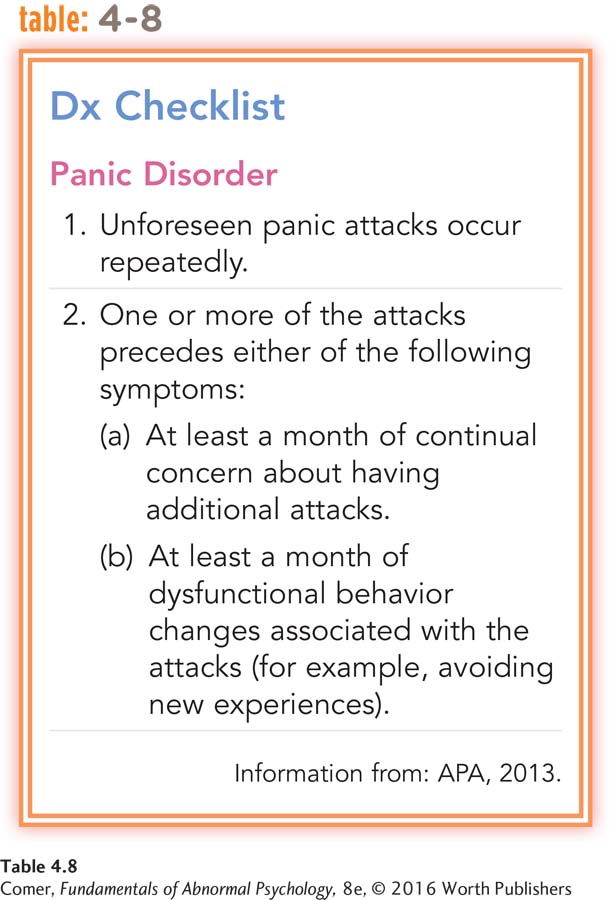

4.4 Panic Disorder

panic attacks Periodic, short bouts of panic that occur suddenly, reach a peak within minutes, and gradually pass.

Sometimes an anxiety reaction takes the form of a smothering, nightmarish panic in which people lose control of their behavior and, in fact, are practically unaware of what they are doing. Anyone can react with panic when a real threat looms up suddenly. Some people, however, experience panic attacks—periodic, short bouts of panic that occur suddenly, reach a peak within minutes, and gradually pass (APA, 2013).

The attacks feature at least four of the following symptoms of panic: palpitations of the heart, tingling in the hands or feet, shortness of breath, sweating, hot and cold flashes, trembling, chest pains, choking sensations, faintness, dizziness, and a feeling of unreality (APA, 2013). Small wonder that during a panic attack many people fear they will die, go crazy, or lose control.

My first panic attack happened when I was traveling for spring break with my mom…. [W]hile I was driving …. a random thought entered my head, ….nd BOOM—

(LeCroy & Holschuh, 2012)

panic disorder An anxiety disorder marked by recurrent and unpredictable panic attacks.

More than one-

Around 2.4 percent of all people in the United States suffer from panic disorder in a given year; more than 5 percent develop it at some point in their lives (Kessler et al., 2012). The disorder tends to develop in late adolescence or early adulthood and is at least twice as common among women as among men. Poor people are 50 percent more likely than wealthier people to experience panic disorder (Sareen et al., 2011).

For reasons that are not understood, the prevalence of this disorder is somewhat higher among white Americans than among minority groups in the United States (Levine et al., 2013). In addition, the features of panic attacks seem to differ somewhat from group to group (Barrera et al., 2010). For example, Asian Americans appear more likely than white Americans to experience dizziness, unsteadiness, and choking, while African Americans seem less likely than white Americans to have those particular symptoms. Surveys indicate that at least one-

As you read earlier, panic disorder is often accompanied by agoraphobia, the broad phobia in which people are afraid to travel to public places where escape might be difficult should they have panic symptoms or become incapacitated. In such cases, the panic disorder typically sets the stage for the development of agoraphobia. That is, after experiencing multiple unpredictable panic attacks, a person becomes increasingly fearful of having new attacks in public places.

The Biological Perspective

In the 1960s, clinicians made the surprising discovery that panic disorder was helped more by certain antidepressant drugs, drugs that are usually used to reduce the symptoms of depression, than by most of the benzodiazepine drugs, the drugs useful in treating generalized anxiety disorder (Klein, 1964; Klein & Fink, 1962). This observation led to the first biological explanations and treatments for panic disorder.

norepinephrine A neurotransmitter whose abnormal activity is linked to panic disorder and depression.

What Biological Factors Contribute to Panic Disorder? To understand the biology of panic disorder, researchers worked backward from their understanding of the antidepressant drugs that seemed to control it. They knew that these particular antidepressant drugs operate in the brain primarily by changing the activity of norepinephrine, yet another one of the neurotransmitters that carries messages between neurons. Given that the drugs were so helpful in eliminating panic attacks, researchers began to suspect that panic disorder might be caused in the first place by abnormal norepinephrine activity.

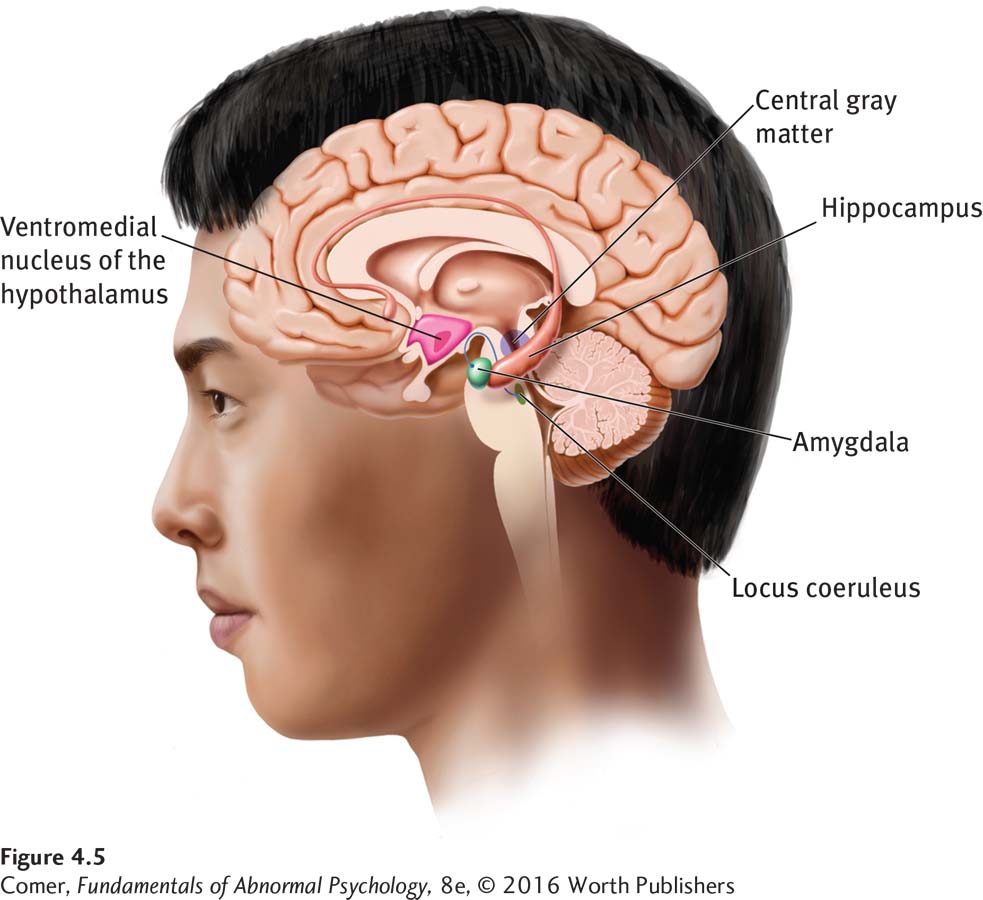

locus coeruleus A small area of the brain that seems to be active in the regulation of emotions. Many of its neurons use norepinephrine.

Several studies produced evidence that norepinephrine activity is indeed irregular in people who suffer from panic attacks. For example, the locus coeruleus is a brain area rich in neurons that use norepinephrine, and it serves as a kind of “on–

These findings strongly tied norepinephrine and the locus coeruleus to panic attacks. However, research conducted in recent years suggests that the root of panic attacks is probably more complicated than a single neurotransmitter or a single brain area. It turns out that panic reactions are produced in part by a brain circuit consisting of areas such as the amygdala, hippocampus, ventromedial nucleus of the hypothalamus, central gray matter, and locus coeruleus (Henn, 2013; Etkin, 2010) (see Figure 4.5). When a person confronts a frightening object or situation, the amygdala is stimulated. In turn, the amygdala stimulates the other brain areas in the circuit, temporarily setting into motion an “alarm and escape” response (increased heart rate, respiration, blood pressure, and the like) that is very similar to a panic reaction (Gray & McNaughton, 1996). Most of today’s researchers believe that this brain circuit—

Note that the brain circuit responsible for panic reactions appears to be different from the one responsible for broad and worry-

Why might some people have abnormalities in norepinephrine activity, locus coeruleus functioning, and other parts of the panic brain circuit? One possibility is that a predisposition to develop such abnormalities is inherited (Gloster et al., 2015; Torgersen, 1990, 1983). Once again, if a genetic factor is at work, close relatives should have higher rates of panic disorder than more distant relatives. Studies do find that among identical twins (twins who share all of their genes), if one twin has panic disorder, the other twin has the same disorder in as many as 31 percent of cases (Tsuang et al., 2004). Among fraternal twins (who share only some of their genes), if one twin has panic disorder, the other twin has the same disorder in only 11 percent of cases (Kendler et al., 1995, 1993).

BETWEEN THE LINES

In Their Words

“Neither a man nor a crowd nor a nation can be trusted to act humanely or to think sanely under the influence of a great fear.”

Bertrand Russell

Drug Therapies As you have just read, researchers discovered in 1962 that certain antidepressant drugs could prevent panic attacks or reduce their frequency. Since the time of this surprising finding, studies across the world have repeatedly confirmed the initial observation (Cuijpers et al., 2014; Stein et al., 2010).

It appears that all antidepressant drugs that restore proper activity of norepinephrine in the locus coeruleus and other parts of the panic brain circuit are able to help prevent or reduce panic symptoms (Pollack, 2005; Redmond, 1985). Such drugs bring at least some improvement to 80 percent of patients who have panic disorder, and the improvement can last indefinitely, as long as the drugs are continued. In addition, alprazolam (Xanax) and other powerful benzodiazepine drugs have also proved effective in the treatment of panic disorder (NIMH, 2013; Bandelow & Baldwin, 2010). Apparently, the benzodiazepines help individuals with this disorder by indirectly affecting the activity of norepinephrine throughout the brain. Clinicians also have found the same antidepressant drugs and powerful benzodiazepines to be helpful in cases of panic disorder accompanied by agoraphobia.

The Cognitive Perspective

Cognitive theorists have come to recognize that biological factors are only part of the cause of panic attacks. In their view, full panic reactions are experienced only by people who further misinterpret the physiological events that are taking place within their bodies. Cognitive treatments are aimed at correcting such misinterpretations.

The Cognitive Explanation: Misinterpreting Bodily Sensations Cognitive theorists believe that panic-

biological challenge test A procedure used to produce panic in participants or clients by having them exercise vigorously or perform some other potentially panic-

In biological challenge tests, researchers produce hyperventilation or other biological sensations by administering drugs or by instructing clinical research participants to breathe, exercise, or simply think in certain ways. As you might expect, participants with panic disorder experience greater upset during these tests than participants without the disorder, particularly when they believe that their bodily sensations are dangerous or out of control (Bunaciu et al., 2012).

Why might some people be prone to such misinterpretations? One possibility is that panic-

anxiety sensitivity A tendency to focus on one’s bodily sensations, assess them illogically, and interpret them as harmful.

Whatever the precise causes of such misinterpretations may be, research suggests that panic-

Cognitive Therapy Cognitive therapists try to correct people’s misinterpretations of their bodily sensations (Craske & Barlow, 2014; Clark & Beck, 2012, 2010). The first step is to educate clients about the general nature of panic attacks, the actual causes of bodily sensations, and the tendency of clients to misinterpret their sensations. The next step is to teach clients to apply more accurate interpretations during stressful situations, thus short-

In addition, cognitive therapists may use biological challenge procedures to induce panic sensations, so that clients can apply their new skills under watchful supervision (Gloster et al., 2014). Individuals whose attacks typically are triggered by a rapid heart rate, for example, may be told to jump up and down for several minutes or to run up a flight of stairs. They can then practice interpreting the resulting sensations appropriately, without dwelling on them.

According to research, cognitive treatments often help people with panic disorder (Wesner et al., 2015; Craske & Barlow, 2014). In studies across the world, around 80 percent of participants given these treatments have become free of panic, compared with only 13 percent of control participants. Cognitive therapy has proved to be at least as helpful as antidepressant drugs or alprazolam in the treatment of panic disorder, sometimes even more so (Bandelow et al., 2015; Baker, 2011). In view of the effectiveness of both cognitive and drug treatments, many clinicians have tried, with some success, to combine them (Cuijpers et al., 2014). For individuals who display both panic disorder and agoraphobia, research suggests that it is most helpful to combine behavioral exposure techniques with cognitive treatments and/or drug therapy (Gloster et al., 2014, 2011).

Summing Up

PANIC DISORDER Panic attacks are periodic, discrete bouts of panic that occur suddenly. Sufferers of panic disorder experience panic attacks repeatedly and unexpectedly and without apparent reason. Panic disorder may be accompanied by agoraphobia in some cases, leading to two diagnoses.

Some biological theorists believe that abnormal norepinephrine activity in the brain’s locus coeruleus may be central to panic disorder. Others believe that related neurotransmitters or a panic brain circuit may also play key roles. Biological therapists use certain antidepressant drugs or powerful benzodiazepines to treat people with this disorder.

Cognitive theorists suggest that panic-