5.1 Stress and Arousal: The Fight-or-Flight Response

autonomic nervous system (ANS) The network of nerve fibers that connect the central nervous system to all the other organs of the body.

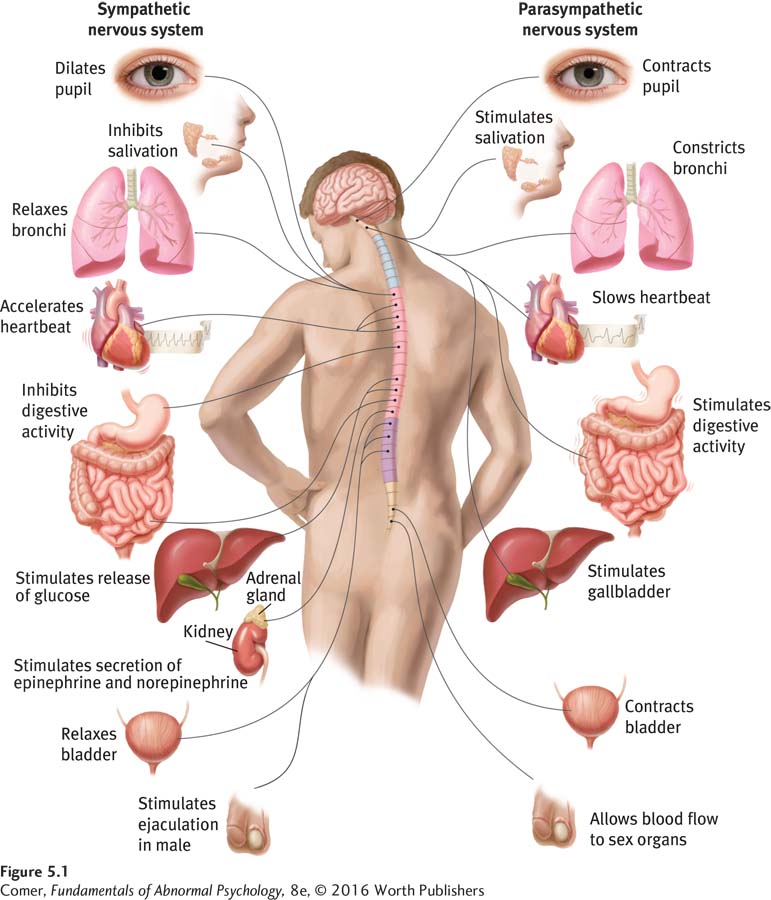

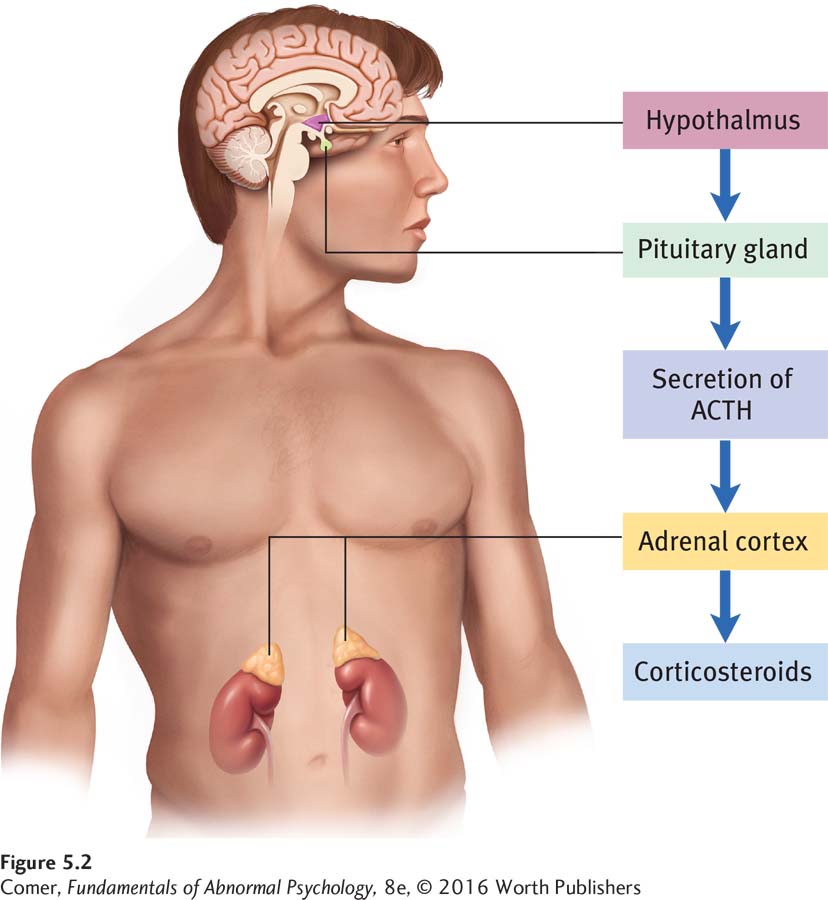

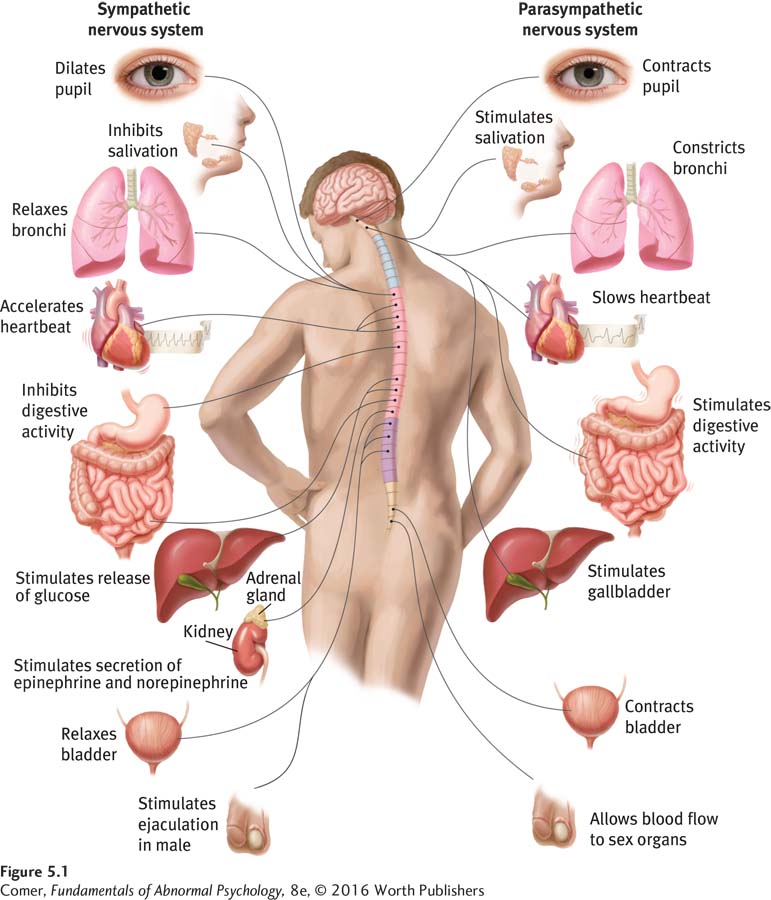

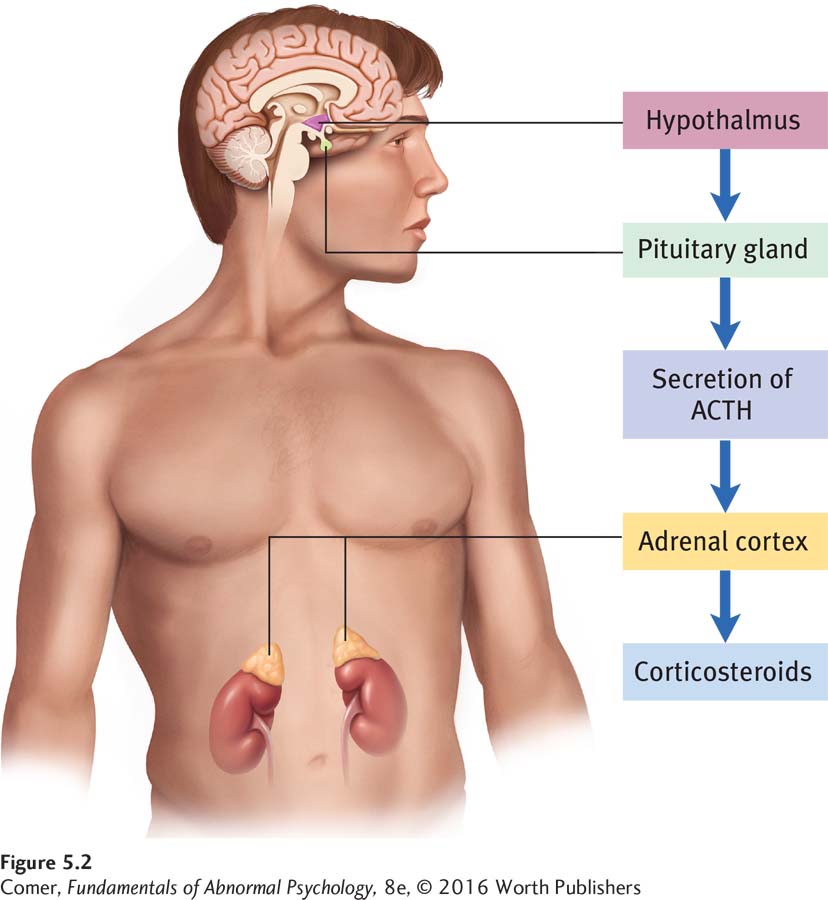

endocrine system The system of glands located throughout the body that help control important activities such as growth and sexual activity.

The features of arousal and fear are set in motion by the brain area called the hypothalamus. When our brain interprets a situation as dangerous, neurotransmitters in the hypothalamus are released, triggering the firing of neurons throughout the brain and the release of chemicals throughout the body. Actually, the hypothalamus activates two important systems—the autonomic nervous system and the endocrine system (Biran et al., 2015). The autonomic nervous system (ANS) is the extensive network of nerve fibers that connect the central nervous system (the brain and spinal cord) to all the other organs of the body. These fibers help control the involuntary activities of the organs—breathing, heartbeat, blood pressure, perspiration, and the like (see Figure 5.1). The endocrine system is the network of glands located throughout the body. (As you read in Chapter 2, glands release hormones into the bloodstream and on to the various body organs.) The ANS and the endocrine system often overlap in their responsibilities. There are two pathways, or routes, by which these systems produce arousal and fear reactions—the sympathetic nervous system pathway and the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal pathway.

Figure 5.1: figure 5.1The autonomic nervous system (ANS) When the sympathetic division of the ANS is activated, it stimulates some organs and inhibits others. The result is a state of general arousal. In contrast, activation of the parasympathetic division leads to an overall calming effect.

sympathetic nervous system The nerve fibers of the autonomic nervous system that quicken the heartbeat and produce other changes experienced as arousal and fear.

When we face a dangerous situation, the hypothalamus first excites the sympathetic nervous system, a group of ANS fibers that work to quicken our heartbeat and produce the other changes that we experience as fear or anxiety. These nerves may stimulate the organs of the body directly—for example, they may directly stimulate the heart and increase heart rate. The nerves may also influence the organs indirectly, by stimulating the adrenal glands (glands located on top of the kidneys), particularly an area of these glands called the adrenal medulla. When the adrenal medulla is stimulated, the chemicals epinephrine (adrenaline) and norepinephrine (noradrenaline) are released. You have already seen that these chemicals are important neurotransmitters when they operate in the brain (see pages 133–134). When released from the adrenal medulla, however, they act as hormones and travel through the bloodstream to various organs and muscles, further producing arousal and fear.

Page 152

parasympathetic nervous system The nerve fibers of the autonomic nervous system that help return bodily processes to normal.

When the perceived danger passes, a second group of autonomic nervous system fibers, called the parasympathetic nervous system, helps return our heartbeat and other body processes to normal. Together the sympathetic and parasympathetic nervous systems help control our arousal and fear reactions.

hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) pathway One route by which the brain and body produce arousal and fear.

corticosteroids A group of hormones, including cortisol, released by the adrenal glands at times of stress.

Figure 5.2: figure 5.2 The endocrine system: The HPA pathway When a person perceives a stressor, the hypothalamus activates the pituitary gland to secrete the adrenocorticotropic hormone, or ACTH, which stimulates the adrenal cortex. The adrenal cortex releases stress hormones called corticosteroids that act on other body organs to trigger arousal and fear reactions.

The second pathway by which arousal and fear reactions are produced is the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) pathway (see Figure 5.2). When we are faced by stressors, the hypothalamus also signals the pituitary gland, which lies nearby, to secrete the adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH), sometimes called the body’s “major stress hormone.” ACTH, in turn, stimulates the outer layer of the adrenal glands, an area called the adrenal cortex, triggering the release of a group of stress hormones called corticosteroids, including the hormone cortisol. These corticosteroids travel to various body organs, where they further produce arousal and fear reactions (Seaward, 2013).

The reactions on display in these two pathways are collectively referred to as the fight-or-flight response, precisely because they arouse our body and prepare us for a response to danger. Each person has a particular pattern of autonomic and endocrine functioning and so a particular way of experiencing arousal and fear. Some people are almost always relaxed, while others typically feel tension, even when no threat is apparent. A person’s general level of arousal and anxiety is sometimes called trait anxiety because it seems to be a general trait that each of us brings to the events in our lives (Tolmunen et al., 2014; Spielberger, 1985, 1972, 1966). Psychologists have found that differences in trait anxiety appear soon after birth (Schwartz et al., 2015; Kagan, 2003).

People also differ in their sense of which situations are threatening (Moore et al., 2014). Walking through a forest may be fearsome for one person but relaxing for another. Flying in an airplane may arouse terror in some people and boredom in others. Such variations are called differences in situation, or state, anxiety.