6.2 Bipolar Disorders

BETWEEN THE LINES

Clinical Oversight

Around 70 percent of people with a bipolar disorder are misdiagnosed at least once (Statistic Brain, 2012).

People with a bipolar disorder experience both the lows of depression and the highs of mania. Many describe their life as an emotional roller coaster, as they shift back and forth between extreme moods. A number of sufferers eventually become suicidal. Their roller coaster ride also has a dramatic impact on relatives and friends (Barron et al., 2014).

What Are the Symptoms of Mania?

Unlike people sunk in the gloom of depression, those in a state of mania typically experience dramatic and inappropriate rises in mood. The symptoms of mania span the same areas of functioning—

A person in the throes of mania has powerful emotions in search of an outlet. The mood of euphoric joy and well-

In the motivational realm, people with mania seem to want constant excitement, involvement, and companionship. They enthusiastically seek out new friends and old, new interests and old, and have little awareness that their social style is overwhelming, domineering, and excessive.

The behavior of people with mania is usually very active. They move quickly, as though there were not enough time to do everything they want to do. They may talk rapidly and loudly, their conversations filled with jokes and efforts to be clever or, conversely, with complaints and verbal outbursts. Flamboyance is not uncommon: dressing in flashy clothes, giving large sums of money to strangers, or even getting involved in dangerous activities.

In the cognitive realm, people with mania usually show poor judgment and planning, as if they feel too good or move too fast to consider possible pitfalls. Filled with optimism, they rarely listen when others try to slow them down. They may also hold an inflated opinion of themselves, and sometimes their self-

Finally, in the physical realm, people with mania feel remarkably energetic. They typically get little sleep yet feel and act wide awake (Armitage & Arnedt, 2011). Even if they miss a night or two of sleep, their energy level may remain high.

Diagnosing Bipolar Disorders

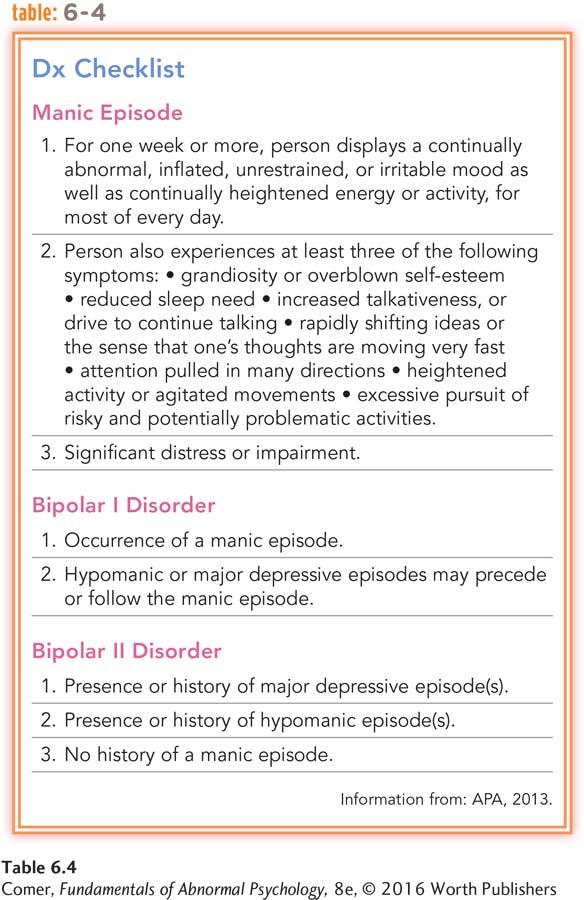

People are considered to be in a full manic episode when for at least one week they display an abnormally high or irritable mood, increased activity or energy, and at least three other symptoms of mania (see Table 6.4). The episode may even include psychotic features such as delusions or hallucinations. When the symptoms of mania are less severe (causing little impairment), the person is said to be having a hypomanic episode (APA, 2013).

bipolar I disorder A type of bipolar disorder marked by full manic and major depressive episodes.

bipolar II disorder A type of bipolar disorder marked by mildly manic (hypomanic) episodes and major depressive episodes.

DSM-

Without treatment, the mood episodes tend to recur for people with either type of bipolar disorder. If a person has four or more episodes within a one-

My mood may swing from one part of the day to another. I may wake up low at 10 am, but be high and excitable by 3 pm. I may not sleep for more than 2 hours one night, being full of creative energy, but by midday be so fatigued it is an effort to breathe.

If my elevated states last more than a few days, my spending can become uncontrollable…. I will sometimes drive faster than usual, need less sleep and can concentrate well, making quick and accurate decisions. At these times I can also be sociable, talkative and fun, focused at times, distracted at others. If this state of elevation continues I often find that feelings of violence and irritability towards those I love will start to creep in….

My thoughts speed up…. I frequently want to be able to achieve several tasks at the same moment…. Physically my energy levels can seem limitless. The body moves smoothly, there is little or no fatigue. I can go mountain biking all day when I feel like this and if my mood stays elevated not a muscle is sore or stiff the next day. But it doesn’t last, my elevated phases are short…. [T]he shift into severe depression or a mixed mood state occurs sometimes within minutes or hours, often within days and will last weeks often without a period of normality….

Initially my thoughts become disjointed and start slithering all over the place…. I start to believe that others are commenting adversely on my appearance or behaviour…. My sleep will be poor and interrupted by bad dreams…. The world appears bleak…. I become repelled by the proximity of people…. I will be overwhelmed by the slightest tasks, even imagined tasks…. Physically there is immense fatigue: my muscles scream with pain…. . Food becomes totally uninteresting….

I start to feel trapped, that the only escape is death…. I become passionate about one subject only at these times of deep and intense fear, despair and rage: suicide…. I have made close attempts on my life ….ver the last few years….

Then inexplicably, my mood will shift again. The fatigue drops from my limbs like shedding a dead weight, my thinking returns to normal, the light takes on an intense clarity, flowers smell sweet and my mouth curves to smile at my children, my husband and I am laughing again. Sometimes it’s for only a day but I am myself again, the person that I was a frightening memory. I have survived another bout of this dreaded disorder….

(Anonymous, 2006)

Surveys from around the world indicate that between 1 and 2.6 percent of all adults are suffering from a bipolar disorder at any given time (Kessler et al., 2012; Merikangas et al., 2011). As many as 4 percent experience one of the bipolar disorders at some time in their life. The bipolar disorders are equally common in women and men, but they are more common among people with low incomes than those with higher incomes (Sareen et al., 2011). Onset usually occurs between the ages of 15 and 44 years. In most untreated cases, the manic and depressive episodes eventually subside, only to recur at a later time.

cyclothymic disorder A disorder marked by numerous periods of hypomanic symptoms and mild depressive symptoms.

Some people have numerous periods of hypomanic symptoms and mild depressive symptoms, a pattern that is called cyclothymic disorder in DSM-

What Causes Bipolar Disorders?

Throughout the first half of the twentieth century, the search for the causes of bipolar disorders made little progress. More recently, biological research has produced some promising clues. The biological insights have come from research into neurotransmitter activity, ion activity, brain structure, and genetic factors.

Neurotransmitters Could overactivity of norepinephrine be related to mania? This was the expectation of clinicians back in the 1960s after investigators first found a relationship between low norepinephrine activity and unipolar depression. Indeed, some research did find the norepinephrine activity of people with mania to be higher than that of control participants (Post et al., 1980, 1978; Schildkraut, 1965).

Because serotonin activity often parallels norepinephrine activity in unipolar depression, theorists at first expected that mania would also be related to high serotonin activity, but no such relationship has been found. Instead, research suggests that mania, like depression, may be linked to low serotonin activity (Hsu et al., 2014; Nugent et al., 2013). Perhaps low activity of serotonin opens the door to a mood disorder and permits the activity of norepinephrine (or perhaps other neurotransmitters) to define the particular form the disorder will take. That is, low serotonin activity accompanied by low norepinephrine activity may lead to depression; low serotonin activity accompanied by high norepinephrine activity may lead to mania.

PsychWatch

Abnormality and Creativity: A Delicate Balance

The ancient Greeks believed that various forms of “divine madness” inspired creative acts, from poetry to performance (Ludwig, 1995). Even today many people expect “creative geniuses” to be psychologically disturbed. A popular image of the artist includes a glass of liquor, a cigarette, and a tormented expression. Classic examples include writer William Faulkner, who suffered from alcoholism and received electroconvulsive therapy for depression; poet Sylvia Plath, who was depressed for most of her life and eventually committed suicide at age 31; and dancer Vaslav Nijinsky, who suffered from schizophrenia and spent many years in institutions. In fact, a number of studies indicate that artists and writers are somewhat more likely than others to suffer from certain mental disorders, particularly bipolar disorders (Kyaga et al., 2013, 2011; Galvez et al., 2011; Sample, 2005).

Why might creative people be prone to such psychological disorders? Some may be predisposed to such disorders long before they begin their artistic careers (Simonton, 2010; Ludwig, 1995). Indeed, creative people often have a family history of psychological problems (Kyaga et al., 2013, 2011). A number also have experienced intense psychological trauma during childhood. English writer Virginia Woolf, for example, endured sexual abuse as a child.

A second explanation for the link between creativity and psychological disorders is that the creative professions offer a welcome climate for those with psychological disturbances. In the worlds of poetry, painting, and acting, for example, emotional expression, unusual thinking, and/or personal turmoil are valued as sources of inspiration and success (Galvez et al., 2011; Sample, 2005).

Much remains to be learned about the relationship between emotional turmoil and creativity, but work in this area has already clarified two important points. First, psychological disturbance is hardly a requirement for creativity. Most “creative geniuses” are, in fact, psychologically stable and happy throughout their entire lives (Kaufman, 2013). Second, mild psychological disturbances relate to creative achievement much more strongly than severe disturbances do (Galvez et al., 2011). For example, nineteenth-

Some artists worry that their creativity would disappear if their psychological suffering were to stop. In fact, however, research suggests that successful treatment for severe psychological disorders more often than not improves the creative process (Jamison, 1995; Ludwig, 1995). Romantic notions aside, severe mental dysfunctioning has little redeeming value, in the arts or anywhere else.

Ion Activity While neurotransmitters play a significant role in the communication between neurons, electrically charged ions seem to play a critical role in relaying messages within a neuron. When a neuron receives an incoming message, its sodium ions (Na+) and potassium ions (K+) flow back and forth between the outside and inside of the neuron’s membrane, producing a wave of electrical activity that travels down the length of the neuron (the axon) and results in its “firing.”

If messages are to travel effectively down the axon, the ions must be able to move easily between the outside and the inside of the neural membrane. Some studies suggest that, among bipolar individuals, irregularities in the transport of these ions may cause neurons to fire too easily (resulting in mania) or to stubbornly resist firing (resulting in depression) (Manji & Zarate, 2011; Li & El-

Brain Structure Brain imaging and postmortem studies have identified a number of abnormal brain structures in people with bipolar disorders (Eker et al., 2014; Chen et al., 2011; Savitz & Drevets, 2011). For example, the basal ganglia and cerebellum of these people tend to be smaller than those of other people, and their dorsal raphe nucleus, striatum, amygdala, hippocampus, and prefrontal cortex each have structural abnormalities. It is not clear what role such structural abnormalities play in bipolar disorders.

Genetic Factors Many theorists believe that people inherit a biological predisposition to develop bipolar disorders (Wiste et al., 2014; Gershon & Nurnberger, 1995). Family pedigree studies support this idea. Identical twins of those with a bipolar disorder have a 40 percent likelihood of developing the same disorder, and fraternal twins, siblings, and other close relatives of such persons have a 5 to 10 percent likelihood, compared with the 1 to 2.6 percent prevalence rate in the general population.

Researchers have also used techniques from molecular biology to more directly examine possible genetic factors. These various undertakings have linked bipolar disorders to genes on chromosomes 1, 4, 6, 10, 11, 12, 13, 15, 18, 20, 21, and 22 (Sinkus et al., 2015; Green et al., 2013; Bigdeli et al., 2013). Such wide-

What Are the Treatments for Bipolar Disorders?

Until the latter part of the twentieth century, people with bipolar disorders were destined to spend their lives on an emotional roller coaster. Psychotherapists reported almost no success, and antidepressant drugs were of limited help. In fact, the drugs sometimes triggered a manic episode (Courtet et al., 2011; Post, 2011, 2005).

lithium A metallic element that occurs in nature as a mineral salt and is an effective treatment for bipolar disorders.

mood stabilizing drugs Psychotropic drugs that help stabilize the moods of people suffering from bipolar disorder. Also known as antibipolar drugs.

Lithium and Other Mood Stabilizers This gloomy picture changed dramatically in 1970 when the FDA approved the use of lithium, a silvery-

Nevertheless, it was lithium that first brought hope to those suffering from bipolar disorders. In her widely read memoir, An Unquiet Mind, psychiatric researcher Kay Redfield Jamison describes how lithium, combined with psychotherapy, enabled her to overcome her bipolar disorder:

I took [lithium] faithfully and found that life was a much stabler and more predictable place than I had ever reckoned. My moods were still intense and my temperament rather quick to the boil, but I could make plans with far more certainty and the periods of absolute blackness were fewer and less extreme….

At this point in my existence, I cannot imagine leading a normal life without both taking lithium and having had the benefits of psychotherapy. Lithium prevents my seductive but disastrous highs, diminishes my depressions, clears out the wool and webbing from my disordered thinking, slows me down, gentles me out, keeps me from ruining my career and relationships, keeps me out of a hospital, alive, and makes psychotherapy possible. [At the same time], ineffably, psychotherapy heals. It makes some sense of the confusion, reins in the terrifying thoughts and feelings, returns some control and hope and possibility of learning from it all…. No pill can help me deal with the problem of not wanting to take pills; likewise, no amount of psychotherapy alone can prevent my manias and depressions. I need both….

(Jamison, 1995)

All manner of research has attested to the effectiveness of lithium and other mood stabilizers in treating manic episodes (Galling et al., 2015; Geddes & Miklowitz, 2013). More than 60 percent of patients with mania improve on these medications. In addition, most such patients have fewer new episodes as long as they continue taking the medications (Malhi et al., 2013). One study found that the risk of relapse is 28 times higher if patients stop taking a mood stabilizer (Suppes et al., 1991). Thus, today’s clinicians usually continue patients on some level of a mood stabilizing drug even after their manic episodes subside (Gao et al., 2010).

In the limited body of research that has been done on this subject, the mood stabilizers also seem to help those with bipolar disorder overcome their depressive episodes, though to a lesser degree than they help with their manic episodes (Malhi et al., 2013; Post, 2011). Given the drugs’ less powerful impact on depressive episodes, many clinicians use a combination of mood stabilizers and antidepressant drugs to treat bipolar depression (Nivoli et al., 2011).

second messengers Chemical changes within a neuron just after the neuron receives a neurotransmitter message and just before it responds.

Researchers do not fully understand how mood stabilizing drugs operate (Malhi et al., 2013; Aiken, 2010). They suspect that the drugs change synaptic activity in neurons, but in a way different from that of antidepressant drugs. The firing of a neuron actually consists of several phases that ensue at lightning speed. When the neurotransmitter binds to a receptor on the receiving neuron, a series of changes occur within the receiving neuron to set the stage for firing. The substances in the neuron that carry out those changes are often called second messengers because they relay the original message from the receptor site to the firing mechanism of the neuron. (The neurotransmitter itself is considered the first messenger.) Whereas antidepressant drugs affect a neuron’s initial reception of neurotransmitters, mood stabilizers appear to affect a neuron’s second messengers.

In a similar vein, it has been found that lithium and other mood stabilizing drugs also increase the production of neuroprotective proteins—key proteins within certain neurons whose job is to prevent cell death. The drugs may increase the health and functioning of those cells and thus reduce bipolar symptoms (Malhi et al., 2013; Gray et al., 2003).

Adjunctive Psychotherapy As Jamison stated in her memoir, psychotherapy alone is rarely helpful for persons with bipolar disorders. At the same time, clinicians have learned that mood stabilizing drugs alone are not always sufficient either. Thirty percent or more of patients with these disorders may not respond to lithium or a related drug, may not receive the proper dose, or may relapse while taking it. In addition, a number of patients stop taking mood stabilizers on their own (Advokat et al., 2014).

BETWEEN THE LINES

Frenzied Masterpiece

George Frideric Handel wrote his Messiah in less than a month during a manic episode (Roesch, 1991).

In view of these problems, many clinicians now use individual, group, or family therapy as an adjunct to mood stabilizing drugs (Reinares et al., 2014; Geddes & Miklowitz, 2013). Most often, therapists use these formats to emphasize the importance of continuing to take medications; to improve social skills and relationships that may be affected by bipolar episodes; to educate patients and families about bipolar disorders; to help patients solve the family, school, and occupational problems caused by their disorder; and to help prevent patients from attempting suicide (Hollon & Ponniah, 2010). Few controlled studies have tested the effectiveness of such adjunctive therapy, but those that have been done, along with numerous clinical reports, suggest that it helps reduce hospitalization, improves social functioning, and increases patients’ ability to obtain and hold a job (Culver & Pratchett, 2010).

Summing Up

BIPOLAR DISORDERS In bipolar disorders, episodes of mania alternate or intermix with episodes of depression. These disorders are much less common than unipolar depression. They may take the form of bipolar I, bipolar II, or cyclothymic disorder.

Mania may be related to high norepinephrine activity along with a low level of serotonin activity. Some researchers have also linked bipolar disorders to improper transport of ions back and forth between the outside and the inside of a neuron’s membrane, others have focused on deficiencies of key proteins and other chemicals within certain neurons, and still others have uncovered abnormalities in key brain structures. Genetic studies suggest that people may inherit a predisposition to these biological abnormalities.

Lithium and other mood stabilizing drugs have proved to be very effective in reducing and preventing the manic and the depressive episodes of bipolar disorders. These drugs may reduce bipolar symptoms by affecting the activity of second messengers or key proteins or other chemicals within certain neurons throughout the brain. Patients tend to fare better when mood stabilizing and/or other psychotropic drugs are combined with adjunctive psychotherapy.