7.4 Is Suicide Linked to Age?

BETWEEN THE LINES

Additional Punishment

Up through the nineteenth century, the bodies of suicide victims in France and England were sometimes dragged through the streets on a frame, head downward, the way criminals were dragged to their executions.

In the United States, the last prosecution for attempted suicide occurred in 1961; the prosecution was not successful.

(Wertheimer, 2001; Fay, 1995)

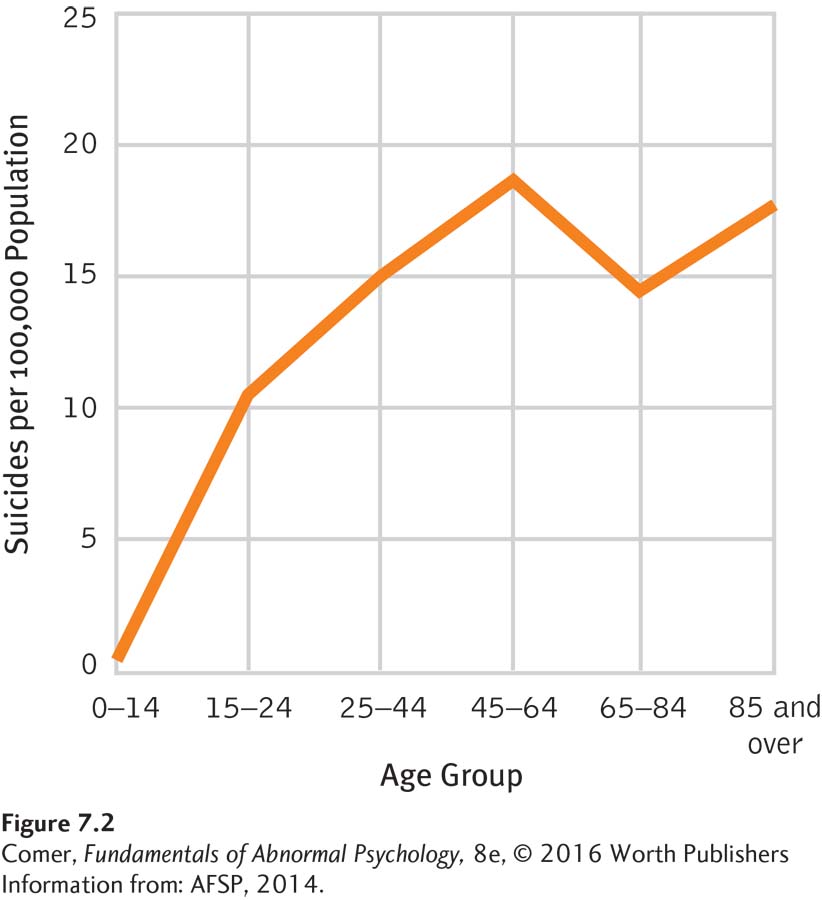

Although people of all ages may try to kill themselves, the likelihood of committing suicide steadily increases with age up through middle age, then decreases during the early stages of old age, and then increases again beginning at age 85 (see Figure 7.2 below). Currently, 1 of every 100,000 people under 15 years of age in the United States kills himself or herself each year, compared with 11 of every 100,000 people between 15 and 24 years old, 19 of every 100,000 between 45 and 64 years old, 15 of every 100,000 between 65 and 84, and 18 of every 100,000 people over age 85 (AFSP, 2014; CDC, 2013). The exceptional rate of suicide among those who are middle-

Clinicians have paid particular attention to self-

Children

Although suicide is infrequent among children, it has been increasing over the past several decades (Dervic et al., 2008). Indeed, more than 6 percent of all deaths among children between the ages of 10 and 14 years are caused by suicide (Arias et al., 2003). Boys outnumber girls by as much as 5 to 1. In addition, it has been estimated that 1 of every 100 children tries to harm himself or herself, and many thousands of children are hospitalized each year for deliberately self-

Researchers have found that suicide attempts by the very young are commonly preceded by such behavioral patterns as running away from home; accident-

Most people find it hard to believe that children fully comprehend the meaning of a suicidal act. They argue that because a child’s thinking is so limited, children who attempt suicide fall into Shneidman’s category of “death ignorers,” like Demaine, who sought to join his mother in heaven. Many child suicides, however, appear to be based on a clear understanding of death and on a clear wish to die (Pfeffer, 2003). In addition, suicidal thinking among even normal children is apparently more common than most people once believed. Clinical interviews with schoolchildren have revealed that between 6 and 33 percent have thought about suicide (Riesch et al., 2008; Culp et al., 1995). Small wonder that many of today’s elementary schools have tried to develop tools and procedures for better identifying and assessing suicide risk among their students (Miller, 2011; Whitney et al., 2011).

Adolescents

Dear Mom, Dad, and everyone else,

I’m sorry for what I’ve done, but I loved you all and I always will, for eternity. Please, please, please don’t blame it on yourselves. It was all my fault and not yours or anyone else’s. If I didn’t do this now, I would have done it later anyway. We all die some day, I just died sooner.

Love,

John

(Berman, 1986)

The suicide of John, age 17, was not an unusual occurrence. Suicidal actions become much more common after the age of 13 than at any earlier age. According to official records, approximately 1,400 teenagers (age 13 to 18), or 7 of every 100,000, commit suicide in the United States each year (Nock et al., 2013). In addition, at least 12 percent of teenagers have persistent suicidal thoughts and 4 percent make suicide attempts (Nock et al., 2013). Because fatal illnesses are uncommon among the young, suicide has become the third leading cause of death in this age group, after accidents and homicides (CDC, 2015). Around 10 percent of all adolescent deaths are the result of suicide.

BETWEEN THE LINES

Therapeutic Failure

More than 55% of suicidal teens actually started therapy before the onset of their suicidal behaviors, but it failed to prevent their actions (Nock et al., 2013).

More than half of teenage suicides have been tied to clinical depression (see PsychWatch on page 238), low self-

Teenagers who consider or attempt suicide are often under great stress. They may be dealing with long-

Some theorists believe that the period of adolescence itself produces a stressful climate in which suicidal actions are more likely. Adolescence is often marked by conflicts, depressed feelings, tensions, and difficulties at home and school. Adolescents tend to react to events more sensitively, angrily, dramatically, and impulsively than individuals in other age groups; thus the likelihood of their engaging in suicidal acts during times of stress is higher (Greening et al., 2008). Finally, the eagerness of adolescents to imitate others, including others who attempt suicide, may set the stage for suicidal action (Apter & Wasserman, 2007). One pioneering study found that 93 percent of adolescent suicide attempters had known someone who had attempted suicide (Conrad, 1992).

Teen Suicides: Attempts Versus Completions Far more teenagers attempt suicide than actually kill themselves—

Why is the rate of suicide attempts so high among teenagers (as well as among young adults)? Several explanations, most pointing to societal factors, have been proposed. First, as the number and proportion of teenagers and young adults in the general population have risen, the competition for jobs, college positions, and academic and athletic honors has intensified for them, leading increasingly to shattered dreams and ambitions (Holinger & Offer, 1993, 1991, 1982). Other explanations point to weakening ties in the family (which may produce feelings of alienation and rejection in many of today’s young people) and to the easy availability of alcohol and other drugs and the pressure to use them among teenagers and young adults (Brent, 2001; Cutler et al., 2001).

The mass media coverage of suicides by teenagers and young adults may also contribute to the high rate of suicide attempts among the young (Gerard et al., 2012). The detailed descriptions of teenage suicide that the media and the arts often offer may serve as models for young people who are contemplating suicide (Cheng et al., 2007). In one of the most famous examples of this phenomenon, just days after the highly publicized suicides of four adolescents in a New Jersey town in 1987, dozens of teenagers across the United States took similar actions (at least 12 of them fatal)—two in the same garage just one week later.

It is worth noting here that a number of pro-

PsychWatch

The Black Box Controversy: Do Antidepressants Cause Suicide?

A major controversy in the clinical field is whether antidepressant drugs are highly dangerous for depressed children and teenagers. Throughout the 1990s, most psychiatrists believed that antidepressants—

Although many clinicians have been pleased by the FDA order, others worry that it may be ill-

The critics of the black box warnings also point to the initial effect that the warnings had on prescription patterns and teenage suicide rates in the United States and other countries. Some studies suggest that during the first two years following the institution of the black box warnings, the number of antidepressant prescriptions fell 22 percent in the United States and the Netherlands, while the rate of teenage suicides rose 14 percent in the United States, the largest suicide rate increase since 1979 (Fawcett, 2007). Although other studies challenge these numbers (Wheeler et al., 2008), it is certainly possible that black box warnings were indirectly depriving many young patients of a medication that they truly needed to help fight depression and head off suicide. Antidepressant prescriptions for depressed teenagers now seem to be rising again, and the effect of this trend reversal on teenage suicide rates certainly awaits careful scrutiny.

A major outgrowth and benefit of the black box controversy is that the FDA recently has expanded its interest in suicidal side effects to drugs other than antidepressants. It now requires pharmaceutical companies to test for suicidal side effects in certain newly developed drugs, such as those for obesity and epilepsy, before such drugs receive FDA approval (Carey, 2008; Harris, 2008). In the past, lethal effects of this kind never came to light until well after drugs had been approved and used by millions of patients.

Teen Suicides: Multicultural Issues Teenage suicide rates vary by ethnicity in the United States. Around 7.5 of every 100,000 white American teenagers commit suicide each year, compared with 5 of every 100,000 African American teens and 5 of every 100,000 Hispanic American teens (Goldston et al., 2008; NAHIC, 2006). Although these numbers certainly indicate that white American teens are more prone to suicide, the rates of the three groups are in fact becoming closer (Baca-

The highest teenage suicide rate of all is displayed by American Indians. Currently, more than 15 of every 100,000 American Indian teenagers commit suicide each year, double the rate of white American teenagers and triple that of other minority teenagers. Clinical theorists attribute this extraordinarily high rate to factors such as the extreme poverty faced by most American Indian teens, their limited educational and employment opportunities, their particularly high rate of alcohol abuse, and the geographical isolation of those who live on reservations (Alcántara & Gone, 2008; Goldston et al., 2008). In addition, it appears that certain American Indian reservations have extreme suicide rates—

The Elderly

Why do people often view the suicides of elderly or chronically sick people as less tragic than that of young or healthy people?

More than 15 of every 100,000 people over the age of 65 in the United States commit suicide, a rate that rises to 18 per 100,000 among the very elderly, as you read earlier (AFSD, 2014). Elderly people commit over 19 percent of all suicides in the United States, yet they account for only 14 percent of the total population (U.S. Census Bureau, 2014).

Many factors contribute to this high suicide rate. As people grow older, all too often they become ill, lose close friends and relatives, lose control over their lives, and lose status in our society (Draper, 2014; O’Riley et al., 2014). Such experiences may result in feelings of hopelessness, loneliness, depression, “burdensomeness,” or inevitability among aged persons and so increase the likelihood that they will attempt suicide (Kim et al., 2014; Cukrowicz et al., 2011). One study found that two-

BETWEEN THE LINES

In Their Words

“What an amount of good nature and humor it takes to endure the gruesome business of growing old.”

Sigmund Freud, 1937

Elderly people are typically more determined than younger people in their decision to die and give fewer warnings, so their success rate is much higher (Dennis & Brown, 2011). An estimated one of every four elderly persons who attempts suicide succeeds (AFSD, 2014). Given the determination of aged persons and their physical decline, some people argue that older persons who want to die are clear in their thinking and should be allowed to carry out their wishes (see InfoCentral below). However, clinical depression appears to play an important role in as many as 60 percent of suicides by the elderly, suggesting that more elderly people who are suicidal should be receiving treatment for their depressive disorders (Levy et al., 2011). In fact, research suggests that treating depression in older persons helps reduce their risk of suicide markedly (Draper, 2014).

InfoCentral

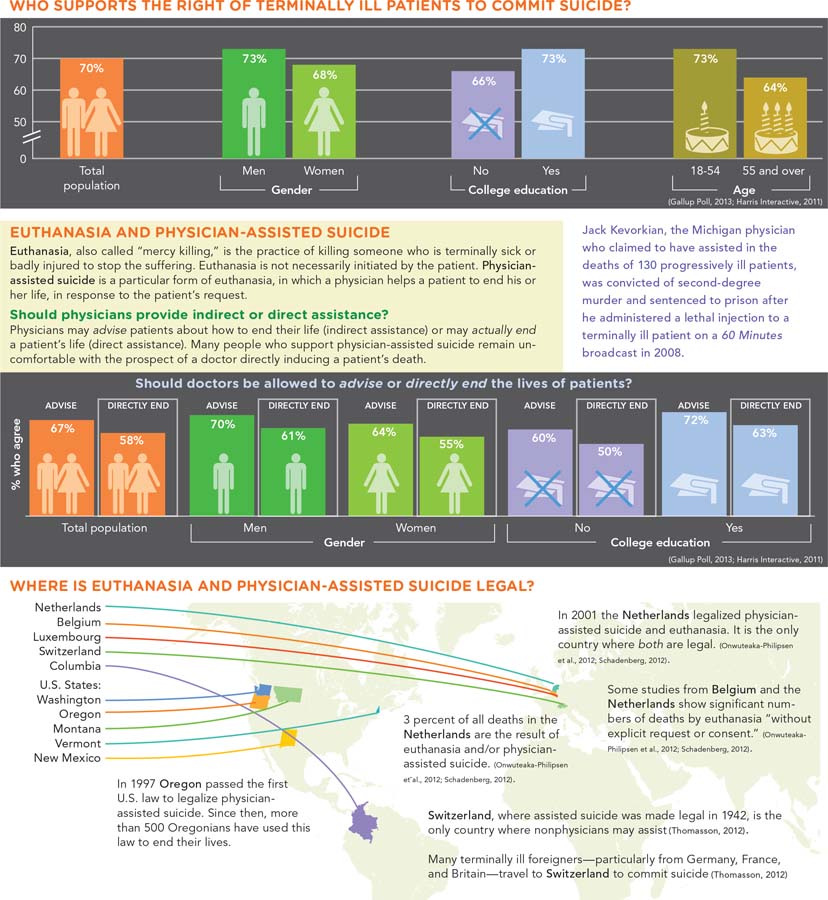

THE RIGHT TO COMMIT SUICIDE

In ancient Greece, citizens with a grave illness or mental anguish could obtain official permission from the Senate to take their own lives (Humphry & Wickett, 1986). In contrast, most Western countries have traditionally discouraged suicide, based on their belief in the “sanctity of life” (Dickens et al., 2008). Today, however, a person’s “right to commit suicide” is receiving more and more support from the public, particularly in connection with ending great pain and terminal illness (Breitbart et al., 2011; Werth, 2004, 2000).

BETWEEN THE LINES

Attitudes Toward Suicide

Hispanic and African Americans have certain beliefs that may make them less likely to attempt suicide. Both groups hold stronger moral objections to suicide than other groups do. In addition, Hispanic Americans have firmer beliefs about the need to cope and survive and feel more responsibility to their families (Oquendo et al., 2005). And African Americans have higher degrees of orthodox religious belief and personal devotion and express more concern about giving others the power to end one’s life (MacDonald, 1998; Neeleman et al., 1998).

The suicide rate among the elderly in the United States is lower in some minority groups (Joe et al., 2014; Alcántara & Gone, 2008). Although American Indians have the highest overall suicide rate, for example, the rate among elderly American Indians is relatively low. The aged are held in high esteem by American Indians and are looked to for the wisdom and experience they have acquired over the years, and this may help account for their low suicide rate. Such high regard is in sharp contrast to the loss of status often experienced by elderly white Americans.

Similarly, the suicide rate is only one-

Summing Up

IS SUICIDE LINKED TO AGE? The likelihood of suicide varies with age. It is uncommon among children, although it has been increasing in that group during the past several decades. Suicide by adolescents is more common than suicide by children, but the numbers have been decreasing over the past decade. Adolescent suicide has been linked to clinical depression, anger, impulsiveness, major stress, and adolescent life itself. Suicide attempts by this age group are numerous. The high attempt rate among adolescents and young adults may be related to the growing number and proportion of young people in the general population, the weakening of family ties, the increased availability and use of drugs among young people, and the broad media coverage of suicide attempts by the young. The rate of suicide among American Indian teens is twice as high as that among white American teens and three times as high as those of African, Hispanic, and Asian American teens.

In Western societies, the elderly are more likely to commit suicide than people in most other age groups. The loss of health, friends, control, and status may produce feelings of hopelessness, loneliness, depression, or inevitability in this age group.