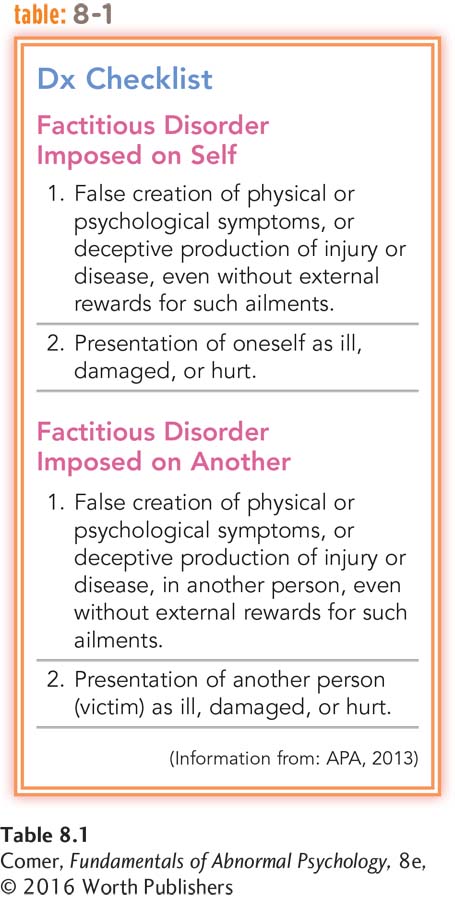

8.1 Factitious Disorder

Like Jarell, people who become physically sick usually go to a physician. Sometimes, however, the physician cannot find a medical cause for the problem and may suspect that other factors are involved. Perhaps the patient is malingering—intentionally feigning illness to achieve some external gain, such as financial compensation or deferment from military service (Crighton et al., 2014).

factitious disorder A disorder in which a person feigns or induces physical symptoms, typically for the purpose of assuming the role of a sick person.

Alternatively, a patient may intentionally produce or feign physical symptoms from a wish to be a patient; that is, the motivation for assuming the sick role may be the role itself (Baig et al., 2015). Physicians would then decide that the patient is manifesting factitious disorder (see Table 8.1). Consider, for example, the symptoms of this lab technician:

A 29-

(Spitzer et al., 1981, p. 33)

Factitious disorder is known popularly as Munchausen syndrome, a label derived from the exploits of Baron von Münchhausen, an eighteenth-

BETWEEN THE LINES

In Their Words

“I would rather have anything wrong with my body than something wrong with my head.”

Sylvia Plath, The Bell Jar

People with factitious disorder often research their supposed ailments and are impressively knowledgeable about medicine (Miner & Feldman, 1998). Many eagerly undergo painful testing or treatment, even surgery (McDermott et al., 2012). When confronted with evidence that their symptoms are factitious, they typically deny the charges and leave the hospital; they may enter another hospital the same day.

Clinical researchers have had a hard time determining the prevalence of factitious disorder, since patients with the disorder hide the true nature of their problem (Kenedi, Sames, & Paice, 2013). Overall, the pattern appears to be more common in women than men. Men, however, may more often have severe cases. The disorder usually begins during early adulthood.

Factitious disorder seems to be particularly common among people who (1) received extensive treatment for a medical problem as children, (2) carry a grudge against the medical profession, or (3) have worked as a nurse, laboratory technician, or medical aide. A number have poor social support, few enduring social relationships, and little family life (McDermott et al., 2012; Feldman et al., 1994).

The precise causes of factitious disorder are not understood (Lawlor & Kirakowski, 2014), although clinical reports have pointed to factors such as depression, unsupportive parental relationships during childhood, and an extreme need for social support that is not otherwise available (McDermott et al., 2012; Ozden & Canat, 1999; Feldman et al., 1995, 1994). Nor have clinicians been able to develop dependably effective treatments for this disorder.

Psychotherapists and medical practitioners often report feelings of annoyance or anger toward people with factitious disorder, feeling that these people are, at the very least, wasting their time. Yet people with the disorder feel they have no control over the problem, and they often experience great distress.

Should society treat or punish those parents who produce Munchausen syndrome by proxy in their children?

In a related pattern, factitious disorder imposed on another, known popularly as Munchausen syndrome by proxy, parents or caretakers make up or produce physical illnesses in their children, leading in some cases to repeated painful diagnostic tests, medication, and surgery (Koetting, 2015; Ayoub, 2010). If the children are removed from their parents and placed in the care of others, their symptoms disappear (see PsychWatch).

Summing Up

FACTITIOUS DISORDER People with factitious disorder feign or induce physical disorders, typically for the purpose of assuming the role of a sick person. The disorder is neither well understood nor well treated. In a related pattern, factitious disorder imposed on another, a parent fabricates or induces a physical illness in his or her child.

PsychWatch

Munchausen Syndrome by Proxy

Tanya, a mere 8 years old, had been hospitalized 127 times over the past five years and undergone 28 different medical procedures—

Cases like Tanya’s have horrified the public and called attention to Munchausen syndrome by proxy. This form of factitious disorder is caused by a caregiver who uses various techniques to induce symptoms in a child—

Between 6 and 30 percent of the victims of Munchausen syndrome by proxy die as a result of their symptoms, and 8 percent of those who survive are permanently disfigured or physically impaired (Flaherty & Macmillan, 2013; Ayoub, 2006). Psychological, educational, and physical development are also affected (Bass & Glaser, 2014; Schreier et al., 2010).

The syndrome is very hard to diagnose and may be more common than clinicians once thought (Ashraf & Thevasagayam, 2014; Feldman, 2004). The parent (usually the mother) seems to be so devoted and caring that others sympathize with and admire her. Yet the physical problems disappear when the child and parent are separated (Koetting, 2015; Scheuerman et al., 2013). In many cases, siblings of the sick child are also victimized (Ayoub, 2010, 2006).

What kind of parent carefully inflicts pain and illness on her own child? The typical Munchausen mother is emotionally needy: she craves the attention and praise she receives for her devoted care of her sick child (Asraf & Thevasagayam, 2014; Noeker, 2004). She may have little social support outside the medical system. Often the mothers have a medical background of some kind—

Law enforcement authorities approach Munchausen syndrome by proxy as a crime—