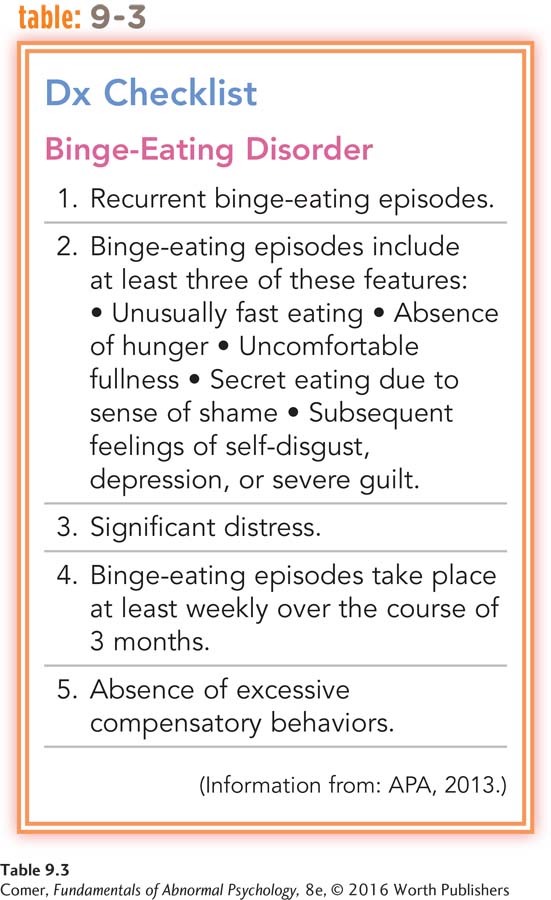

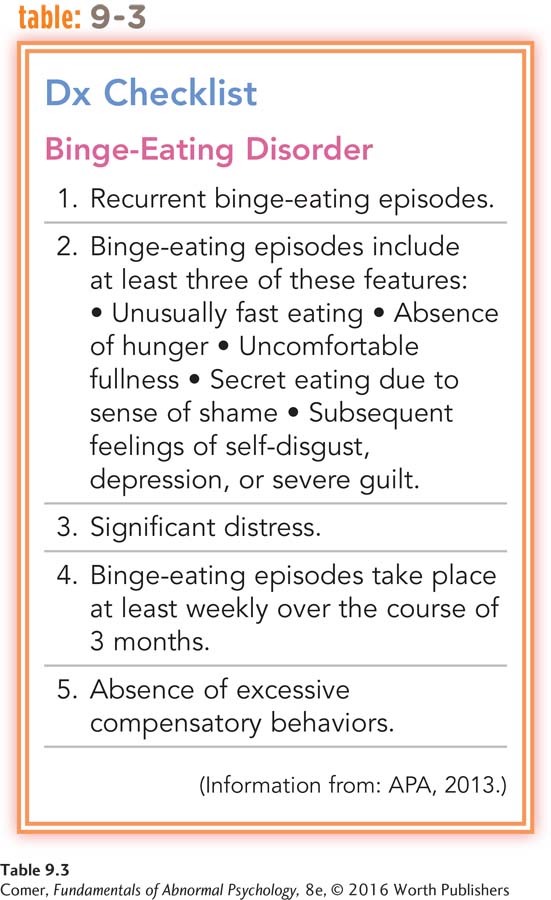

Like those with bulimia nervosa, people with binge-eating disorder engage in repeated eating binges during which they feel no control over their eating (APA, 2013). However, they do not perform inappropriate compensatory behavior (see Table 9.3). As a result of their frequent binges, around two-thirds of people with binge-eating disorder become overweight or even obese (Brauhardt et al., 2014).

Binge-eating disorder was first identified more than 50 years ago as a pattern common among many overweight people (Stunkard, 1959). It is important to recognize, however, that most overweight people do not engage in repeated binges; their weight results from frequent overeating and/or a combination of biological, psychological, and sociocultural factors (ANAD, 2014).

Between 2 and 7 percent of the population have binge-eating disorder (Brownley et al., 2015; Smink et al., 2013). The binges that characterize this pattern are similar to those seen in bulimia nervosa, particularly the amount of food eaten and the sense of loss of control experienced during the binge. Moreover, like people with bulimia nervosa or anorexia nervosa, those with binge-eating disorder typically are preoccupied with food, weight, and appearance; base their evaluation of themselves largely on their weight and shape; misperceive their body size and are extremely dissatisfied with their body; struggle with feelings of depression, anxiety, and perfectionism; may abuse substances; and typically first develop the disorder in adolescence or young adulthood (Brauhardt et al., 2014; Pearl et al., 2014). On the other hand, although they aspire to limit their eating, people with binge-eating disorder are not as driven to thinness as those with anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa. Also, unlike the other eating disorders, binge-eating disorder does not necessarily begin with efforts at extreme dieting, nor are there large gender differences in the prevalence of binge-eating disorder (Davis, 2015; Grucza et al., 2007).