14.3 Childhood Depressive and Bipolar Disorders

Like Billy, the boy you read about at the beginning of this chapter, around 2 percent of children and 8 percent of adolescents currently experience a major depressive disorder (Mash & Wolfe, 2015). As many as 20 percent of adolescents experience at least one depressive episode during their teen years. In addition, many clinicians believe that children may experience bipolar disorder.

Major Depressive Disorder

Very young children lack some of the cognitive skills—

Clinical depression is much more common among teenagers than among young children. Adolescence is, under the best of circumstances, a difficult and confusing time, marked by angst, hormonal and bodily changes, mood changes, complex relationships, and new explorations (see MindTech below). For some teens, these “normal” upsets of adolescence cross the line into clinical depression. As you read in Chapter 7, suicidal thoughts and attempts are particularly common among adolescents—

Interestingly, while there is no difference between the rates of depression in boys and girls before the age of 13, girls are twice as likely as boys to be depressed by the age of 16 (Frost et al., 2015; Merikangas et al., 2010). Why this gender shift? Several factors have been suggested, including hormonal changes and the fact that females increasingly experience more stressors than males. One explanation also focuses on teenage girls’ growing dissatisfaction with their bodies. Whereas boys tend to like the increase in muscle mass and other body changes that accompany puberty, girls often detest the increases in body fat and weight gain that they experience during puberty and beyond. Raised in a society that values extreme thinness as the aesthetic female ideal, many adolescent girls feel imprisoned by their own bodies, have low self-

For years, it was generally believed that childhood and teenage depression would respond well to the same treatments that have been of help to depressed adults—

MindTech

Parent Worries on the Rise

Parent Worries on the Rise

Parents have always worried about their children—

What exactly do parents worry about when their children go online, and who is worrying the most? Researchers Danah Boyd and Eszter Hargittai (2013) surveyed more than 1,000 parents across the United States and found that safety is at the heart of parents’ anxiety. Almost two-

These areas of anxiety were not distributed evenly among parents. African American, Hispanic American, and Asian American parents were much more likely than white American parents to have these concerns. Urban parents were more fearful than suburban and rural parents. Lower-

What can today’s parents do to address their concerns about their children’s online experiences and behaviors?

Mothers expressed more fear than fathers about their children being bullied online. Parents of daughters were more concerned than parents of sons about their children meeting harmful strangers and being exposed to violence online. And politically conservative and moderate parents expressed significantly more anxiety than liberal parents about their children viewing pornography or meeting strangers online.

In the early days of the Internet, parents would address concerns of this kind by supervising and restricting their children’s online time and access. But those “good old days” are now gone, given the increasing number of U.S. teens who own a smartphone (almost half of them) and the easy access teens have to computers and tablets in so many locations outside the home (Fondas, 2014). In turn, parental anxiety continues to rise.

In one development, the National Institute of Mental Health recently sponsored a massive six-

A second development has been the discovery that antidepressant drugs may be very dangerous for some depressed children and teenagers. As you read in Chapter 7, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) concluded in 2004, based on a number of clinical reports, that the drugs may produce an increased risk of suicidal behavior for certain children and adolescents, especially during the first few months of treatment. Thus, the FDA ordered that all antidepressant containers carry “black box” warnings stating that the drugs “increase the risk of suicidal thinking and behavior in children.”

Arguments about the wisdom of this FDA order have since followed. Although most clinicians agree that the drugs may indeed increase the risk of suicidal thoughts and attempts in as many as 2 to 4 percent of young patients, some have noted that the overall risk of suicide may actually be reduced for the vast majority of children who take the drugs (Isacsson & Rich, 2014; Vela et al., 2011). They point out, for example, that suicides among children and teenagers decreased by 30 percent in the decade leading up to 2004, as the number of antidepressant prescriptions provided to children and teenagers were soaring.

BETWEEN THE LINES

In Their Words

“It is an illusion that youth is happy, an illusion of those who have lost it.”

W. Somerset Maugham, Of Human Bondage, 1915

While the findings of the TADS study and questions about antidepressant drug safety continue to be sorted out, these two developments serve to highlight once again the importance of research, particularly in the treatment realm. We are reminded that treatments that work for individuals of a certain age, gender, race, or ethnic background may be ineffective or even dangerous for other groups of people.

Bipolar Disorder and Disruptive Mood Dysregulation Disorder

For decades, bipolar disorder was thought to be exclusively an adult disorder, and it was believed that its earliest age of onset is the late teens (APA, 2013). However, since the mid-

Most theorists believe that these numbers reflect not an increase in the prevalence of bipolar disorders among children but rather a new diagnostic trend. The question is whether this trend is accurate. Many clinical theorists believe that the diagnosis of bipolar disorder is currently being overapplied to children and adolescents (Mash & Wolfe, 2015; Paris, 2014). They suggest that the label has become a clinical catchall that is being applied to almost every explosive, aggressive child. In fact, symptoms of rage and aggression, along with depression, dominate the clinical picture of most children who receive a bipolar diagnosis (Roy et al., 2013). The children may not even manifest the symptoms of mania or the mood swings that characterize adult bipolar disorder.

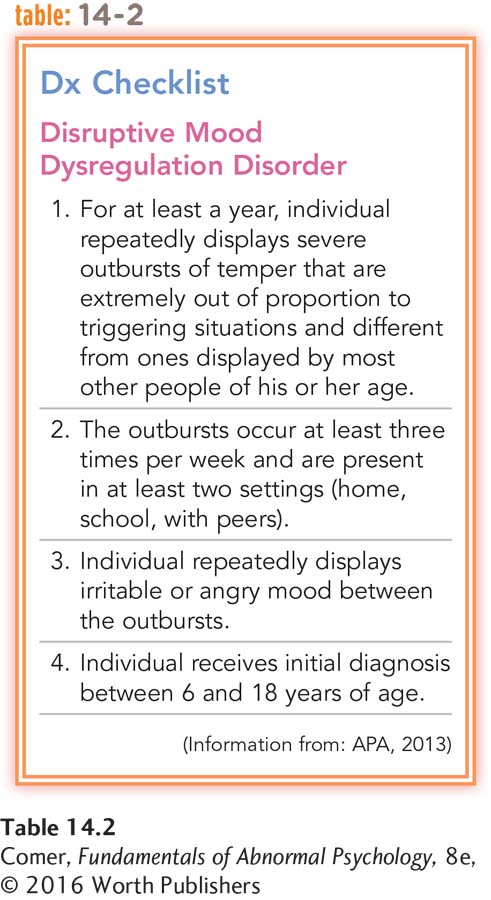

disruptive mood dysregulation disorder A childhood disorder marked by severe recurrent temper outbursts and a persistent irritable or angry mood.

The DSM-

This issue is particularly important because the rise in diagnoses of bipolar disorder has been accompanied by an increase in the number of children who are prescribed adult medications (Toteja et al., 2014; Chang et al., 2010; Grier et al., 2010). Around one-

Summing Up

CHILDHOOD DEPRESSIVE AND BIPOLAR DISORDERS Two percent of children and 8 percent of adolescents experience depression. In recent years, the TADS study and the FDA “black box” ruling have raised questions about the most appropriate treatments for teens with depression. In addition, the past two decades have witnessed an enormous increase in the number of children and adolescents who receive diagnoses of bipolar disorder. Such diagnoses are expected to decrease now that DSM-