15.1 Old Age and Stress

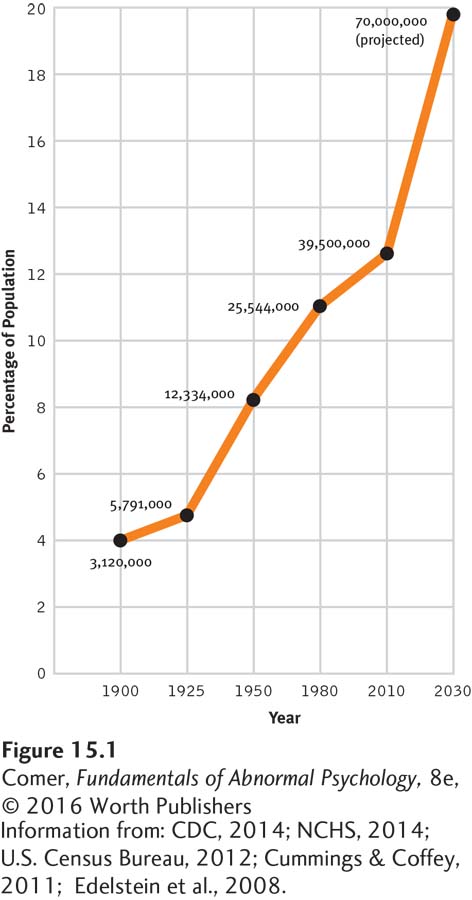

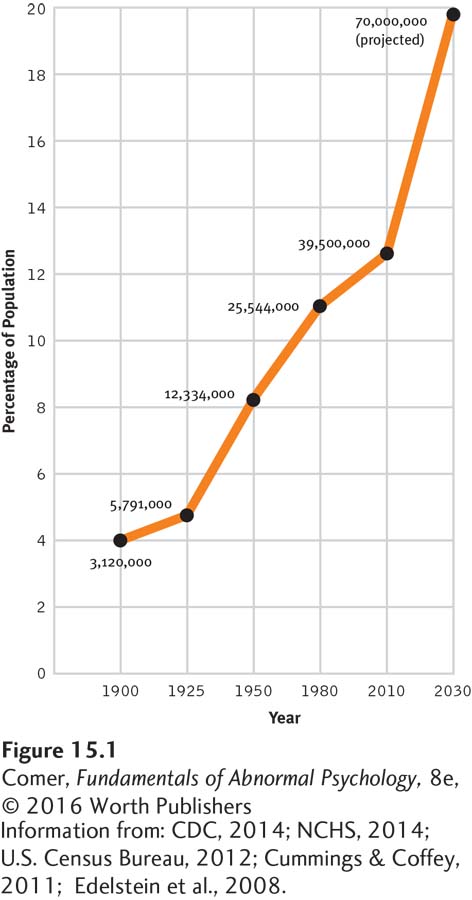

Old age is usually defined in our society as the years past age 65. By this account, around 43 million people in the United States are “old,” representing 13.6 percent of the total population; this is a 14-fold increase since 1900 (CDC, 2014; NCHS, 2014) (see Figure 15.1). It has also been estimated that there will be 70 million elderly people in the United States by the year 2030—more than 20 percent of the population. Not only is the overall population of the elderly on the rise, but also the number of people over 85 will double in the next 10 years. Indeed, people over 85 represent the fastest-growing segment of the population in the United States and in most countries around the world. Older women outnumber older men by almost 3 to 2 (NCHS, 2014).

Figure 15.1: figure 15.1 On the rise The population of people age 65 and older in the United States has increased 14-fold since the beginning of the twentieth century. The percentage of elderly people in the population increased from 4 percent in 1900 to 13 percent in 2010. It is currently 13.6 percent and is expected to be more than 20 percent in 2030. (Information from: CDC, 2014; NCHS, 2014; U.S. Census Bureau, 2012; Cummings & Coffey, 2011; Edelstein et al., 2008.)

Like childhood, old age brings special pressures, unique upsets, and major biological changes (Gerst-Emerson et al., 2014). People become more prone to illness and injury as they age (Nunes et al., 2014). About half of adults over 65 have two or three chronic illnesses, and 15 percent have four or more (NCHS, 2014). In addition, elderly people are likely to be contending with the stress of loss—the loss of spouses, friends, and adult children; of former activities and roles; of hearing and vision (Heine & Browning, 2014). Many lose their sense of purpose after they retire (Murayama et al., 2014). Some also have to adjust to the loss of favored pets and possessions.

geropsychology The field of psychology concerned with the mental health of elderly people.

The stresses of aging need not necessarily cause psychological problems (see PsychWatch below). In fact, some older people, particularly those who seek social contacts and those who maintain a sense of control over their lives, use the changes that come with aging as opportunities for learning and growth (Murayama et al., 2014). For example, the number of elderly—often physically limited—people who use the Internet to connect with people of similar ages and interests doubled between 2000 and 2004, doubled again between 2004 and 2007, and doubled yet again by 2010 (Oinas-Kukkonen & Mantila, 2010). For other elderly people, however, the stresses of old age do lead to psychological difficulties. Studies indicate that more than 20 percent of elderly people meet the criteria for a mental disorder and as many as half of all elderly people would benefit from some degree of mental health services, yet fewer than 20 percent actually receive them (APA, 2014). Geropsychology, the field of psychology dedicated to the mental health of elderly people, has developed almost entirely within the last four decades, and at present only 4 percent of clinicians work primarily with elderly persons (APA, 2014; Fiske et al., 2011).

Page 503

What kinds of attitudes and activities might help people enter old age with peace of mind and positive anticipation?

The psychological problems of elderly people may be divided into two groups. One group consists of disorders that may be common among people in all age groups but are often connected to the process of aging when they occur in an elderly person. These include depressive, anxiety, and substance use disorders. The other group consists of disorders of cognition, such as delirium, mild neurocognitive disorders, and major neurocognitive disorders that result from brain abnormalities. As in Harry’s case, these brain abnormalities are most often tied to aging, but they also can sometimes occur when people are younger. Elderly people with one of these psychological problems often display other such problems. For example, many who suffer from neurocognitive disorders also deal with depression and anxiety (Lebedeva et al., 2014).

PsychWatch

Welcome to the club A 100-year-old woman and a 99-year-old man chat during a party for centenarians in Woodbridge, Connecticut.

Clinicians suggest that aging need not inevitably lead to psychological problems. Nor apparently does it always lead to physical problems.

There are currently 65,000 centenarians in the United States—people who are 100 years old or older. When researchers have studied these people—often called the “oldest old”—they have been surprised to learn that centenarians are on average more healthy, positive, clearheaded, and agile than those in their 80s and early 90s (da Rosa et al., 2014; Zhou et al., 2011). Although some certainly experience cognitive decline, more than half remain perfectly alert. Many of the oldest old are, in fact, still employed, sexually active, and able to enjoy the outdoors and the arts. What is their greatest fear? The fear of significant cognitive decline. According to one study, many people in their 90s and older fear the prospect of mental deterioration more than they fear death (Boeve et al., 2003).

Some scientists believe that people who live this long carry “longevity” genes that make them resistant to disabling or terminal infections (Garatachea et al., 2014; He et al., 2014). Indeed, centenarians are 20 times more likely than other elderly people to have had a relative who also lived to a very old age (D.I., 2014). Other researchers point to engaged lifestyles and “robust” personalities that help the oldest old meet life’s challenges with optimism and a sense of challenge (da Rosa et al., 2014; Martin et al., 2010, 2009). The centenarians themselves often credit a good frame of mind or regular behaviors that they have maintained for many years—for example, eating healthful food, getting regular exercise, and not smoking (D.I., 2014). Said one 96-year-old retired math and science teacher, “You can’t sit. . . . You have to keep moving” (Duenwald, 2003).