16.1 Law and Mental Health

Two social institutions have a particularly strong impact on the mental health profession: the legislative and judicial systems. These institutions—

BETWEEN THE LINES

Growing Involvement

It is estimated that mental health practitioners participate in 1 million court cases in the United States each year.

(Kambam & Benedek, 2010).

This relationship has two distinct aspects. On the one hand, mental health professionals often play a role in the criminal justice system, as when they are called upon to help the courts assess the mental stability of people accused of crimes. They responded to this call in the Hinckley case, as you will see, and in thousands of other cases. This aspect of the relationship is sometimes termed psychology in law; that is, clinical practitioners and researchers operate within the legal system. On the other hand, there is another aspect to the relationship, called law in psychology. The legislative and judicial systems act upon the clinical field, regulating certain aspects of mental health care. The courts may, for example, force some people to enter treatment, even against their will. In addition, the law protects the rights of patients.

forensic psychology The branch of psychology concerned with intersections between psychological practice and research and the judicial system.

The intersections between the mental health field and the legal and judicial systems are collectively referred to as forensic psychology (APA, 2015). Forensic psychologists or psychiatrists (or related mental health professionals) may perform such varied activities as testifying in trials, researching the reliability of eyewitness testimony, or helping police profile the personality of a serial killer on the loose.

How Do Clinicians Influence the Criminal Justice System?

To arrive at just and appropriate punishments, the courts need to know whether defendants are responsible for the crimes they commit and capable of defending themselves in court. If not, it would be inappropriate to find defendants guilty or punish them in the usual manner. The courts have decided that in some instances people who suffer from severe mental instability may not be responsible for their actions or may not be able to defend themselves in court, and so should not be punished in the usual way. Although the courts make the final judgment as to mental instability, their decisions are guided to a large degree by the opinions of mental health professionals.

criminal commitment A legal process by which people accused of a crime are judged mentally unstable and sent to a treatment facility.

not guilty by reason of insanity (NGRI) A verdict stating that defendants are not guilty of a crime because they were insane at the time of the crime.

When people accused of crimes are judged to be mentally unstable, they are usually sent to a mental institution for treatment, a process called criminal commitment. Actually there are several forms of criminal commitment. In one, people are judged mentally unstable at the time of their crimes and so innocent of wrongdoing. They may plead not guilty by reason of insanity (NGRI) and bring mental health professionals into court to support their claim. When people are found not guilty on this basis, they are committed for treatment until they improve enough to be released.

In a second form of criminal commitment, people are judged mentally unstable at the time of their trial and so are considered unable to understand the trial procedures and defend themselves in court. They are committed for treatment until they are competent to stand trial. Once again, the testimony of mental health professionals helps determine the defendant’s psychological functioning.

These judgments of mental instability have stirred many arguments. Some people consider the judgments to be loopholes in the legal system that allow criminals to escape proper punishment for wrongdoing. Others argue that a legal system simply cannot be just unless it allows for extenuating circumstances, such as mental instability. The practice of criminal commitment differs from country to country. In this chapter you will see primarily how it operates in the United States. Although the specific procedures of each country may differ, most countries grapple with the same issues and decisions that you will read about here.

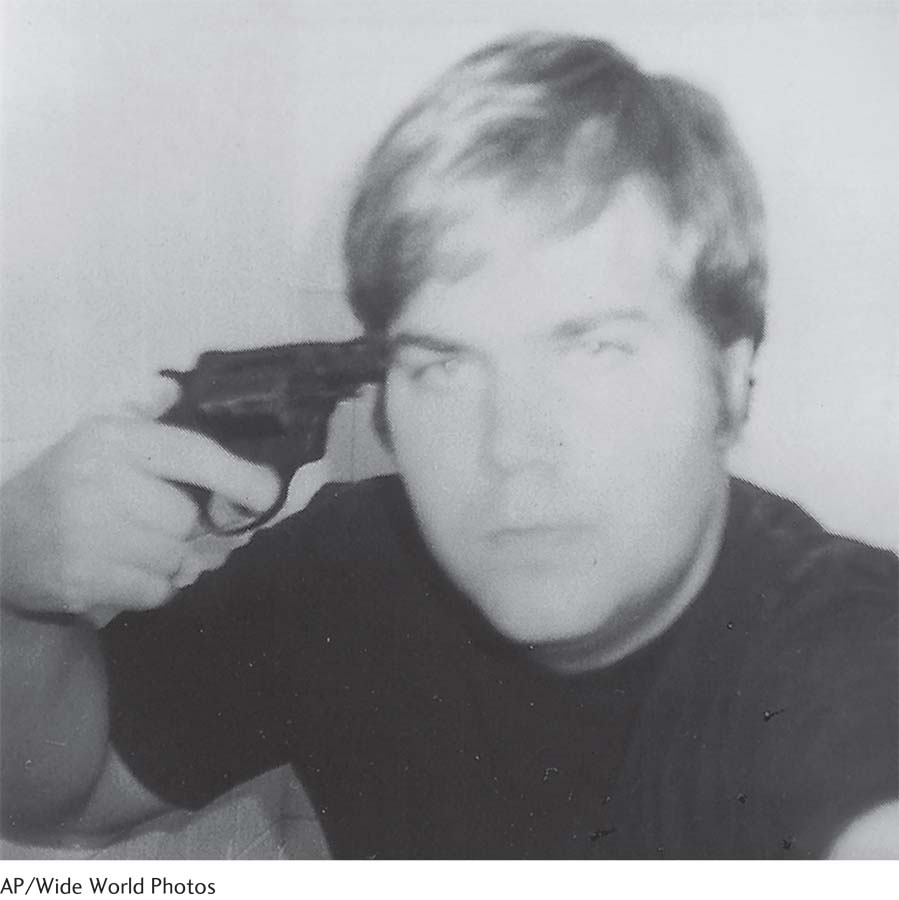

Criminal Commitment and Insanity During Commission of a Crime Consider once again the case of John Hinckley. Was he insane at the time he shot the president? If insane, should he be held responsible for his actions? On June 21, 1982, 15 months after he shot four men in the nation’s capital, a jury pronounced Hinckley not guilty by reason of insanity. Hinckley thus joined Richard Lawrence, a house painter who shot at Andrew Jackson in 1835, and John Schrank, a saloonkeeper who shot former president Teddy Roosevelt in 1912, as a would-

M’Naghten test A legal standard that holds people to be insane at the time they committed a crime if, because of a mental disorder, they did not know the nature of the act or did not know right from wrong.

It is important to recognize that “insanity” is a legal term. That is, the definition of “insanity” used in criminal cases was written by legislators, not by clinicians. Defendants may have mental disorders but not necessarily qualify for a legal definition of insanity. Modern Western definitions of insanity can be traced to the murder case of Daniel M’Naghten in England in 1843. M’Naghten shot and killed Edward Drummond, the secretary to British prime minister Robert Peel, while trying to shoot Peel. Because of M’Naghten’s apparent delusions of persecution, the jury found him to be not guilty by reason of insanity. The public was outraged by this decision, and their angry outcry forced the British law lords to define the insanity defense more clearly. This legal definition, known as the M’Naghten test, or M’Naghten rule, stated that having a mental disorder at the time of a crime does not by itself mean that the person was insane; the defendant also had to be unable to know right from wrong. The state and federal courts in the United States adopted this test as well.

irresistible impulse test A legal standard that holds people to be insane at the time they committed a crime if they were driven to do so by an uncontrollable “fit of passion.”

In the late nineteenth century some state and federal courts in the United States, dissatisfied with the M’Naghten rule, adopted a different test—

Durham test A legal standard that holds people to be insane at the time they committed a crime if their act was the result of a mental disorder or defect.

For years state and federal courts chose between the M’Naghten test and the irresistible impulse test to determine the sanity of criminal defendants. For a while a third test, called the Durham test, also became popular, but it was soon replaced in most courts. This test, based on a decision handed down by the Supreme Court in 1954 in the case of Durham v. United States, stated simply that people are not criminally responsible if their “unlawful act was the product of mental disease or mental defect.” This test was meant to offer more flexibility in court decisions, but it proved too flexible. Insanity defenses could point to such problems as alcoholism or other forms of substance abuse and conceivably even headaches or ulcers, which were listed as psychophysiological disorders in DSM-

American Law Institute test A legal standard that holds people to be insane at the time they committed a crime if, because of a mental disorder, they did not know right from wrong or could not resist an uncontrollable impulse to act.

In 1955 the American Law Institute (ALI) developed a test that combined aspects of the M’Naghten, irresistible impulse, and Durham tests. The American Law Institute test held that people are not criminally responsible if at the time of a crime they had a mental disorder or defect that prevented them from knowing right from wrong or from being able to control themselves and follow the law. For a time the new test became the most widely accepted legal test of insanity. After the Hinckley verdict, however, there was a public uproar over the “liberal” ALI guidelines, and people called for tougher standards.

BETWEEN THE LINES

In Their Words

“I think John Hinckley will be a threat the rest of his life. He is a time bomb.”

U.S. Attorney, 1982

“Without doubt, [John Hinckley] is the least dangerous person on the planet.”

Attorney for John Hinckley, applying for increased privileges for his client, 2003

Partly in response to this uproar, the American Psychiatric Association recommended in 1983 that people should be found not guilty by reason of insanity only if they did not know right from wrong at the time of the crime; an inability to control themselves and to follow the law should no longer be sufficient grounds for a judgment of insanity. In short, the association was calling for a return to the M’Naghten test. This test now is used in all cases tried in federal courts and in about half of the state courts. The more liberal ALI standard is still used in the remaining state courts, except in Idaho, Kansas, Montana, and Utah, which have more or less done away with the insanity plea altogether.

People suffering from severe mental disorders in which confusion is a major feature may not be able to tell right from wrong or to control their behavior. It is therefore not surprising that around two-

WHAT CONCERNS ARE RAISED BY THE INSANITY DEFENSE? Despite the changes in the insanity tests, criticism of the insanity defense continues (MacKinnon & Fiala, 2015; Slovenko, 2011, 2004, 2002). One concern is the fundamental difference between the law and the science of human behavior. The law assumes that individuals have free will and are generally responsible for their actions. Several models of human behavior, in contrast, assume that physical or psychological forces act to determine the individual’s behavior. Inevitably, then, legal definitions of insanity and responsibility will differ from those suggested by clinical research.

A second criticism points to the uncertainty of scientific knowledge about abnormal behavior. During a typical insanity defense trial, the testimony of defense clinicians conflicts with that of clinicians hired by the prosecution, and so the jury must weigh the claims of “experts” who disagree in their assessments. Some people see this lack of professional agreement as evidence that clinical knowledge in some areas may be too incomplete to be allowed to influence important legal decisions (Bartol & Bartol, 2015). Others counter that the field has made great strides—

Even with helpful scales in hand, however, clinicians making judgments of legal insanity face a problem that is difficult to overcome: they must evaluate a defendant’s state of mind during an event that took place weeks, months, or years earlier. Because mental states can and do change over time and across situations, clinicians can never be entirely certain that their assessments of mental instability at the time of the crime are accurate.

BETWEEN THE LINES

33 Years Later

Currently 60 years of age, John Hinckley is a patient at St. Elizabeths Hospital in Washington, DC. A federal judge has granted him furlough privileges, including a 17-

Perhaps the most common criticism of the insanity defense is that it allows dangerous criminals to escape punishment. Granted, some people who successfully plead insanity are released from treatment facilities just months after their acquittal. Yet the number of such cases is quite small (Asmar, 2014; Steadman et al., 1993; Callahan et al., 1991). According to surveys, the public dramatically overestimates the percentage of defendants who plead insanity, guessing it to be 30 to 40 percent, when in fact it is less than 1 percent. Moreover, only a minority of these defendants fake or exaggerate their psychological symptoms, and only 26 percent of those who plead insanity are actually found not guilty on this basis. In all, less than 1 of every 400 defendants in the United States is found not guilty by reason of insanity, and, in most such cases, the prosecution has agreed to the appropriateness of the plea (see PsychWatch below).

PsychWatch

Famous Insanity Defense Cases

1977 In Michigan, Francine Hughes poured gasoline around the bed where her husband, Mickey, lay in a drunken stupor. Then she lit a match and set him on fire. At her trial she explained that he had beaten her repeatedly for 14 years and had threatened to kill her if she tried to leave him. The jury found her not guilty by reason of temporary insanity, making her into a symbol for many abused women across the nation.

1978 David “Son of Sam” Berkowitz, a serial killer in New York City, explained that a barking dog had sent him demonic messages to kill. Although two psychiatrists assessed him as psychotic, he was found guilty of his crimes. Long after his trial, he said that he had actually made up the delusions.

1979 Kenneth Bianchi, one of the pair known as the Hillside Strangler, entered a plea of not guilty by reason of insanity but was found guilty along with his cousin of sexually assaulting and murdering women in the Los Angeles area in late 1977 and early 1978. He claimed that he had multiple personalities.

1980 In December, Mark David Chapman murdered John Lennon. Chapman later explained that he had killed the rock music legend because he believed Lennon to be a “sell-

1981 In an attempt to prove his love for actress Jodie Foster, John Hinckley Jr. tried to assassinate President Ronald Reagan. Hinckley was found not guilty by reason of insanity and was committed to St. Elizabeth’s Hospital for the criminally insane in Washington, DC, where he remains today.

1992 Jeffrey Dahmer, a 31-

1994 On June 23, 1993, 24-

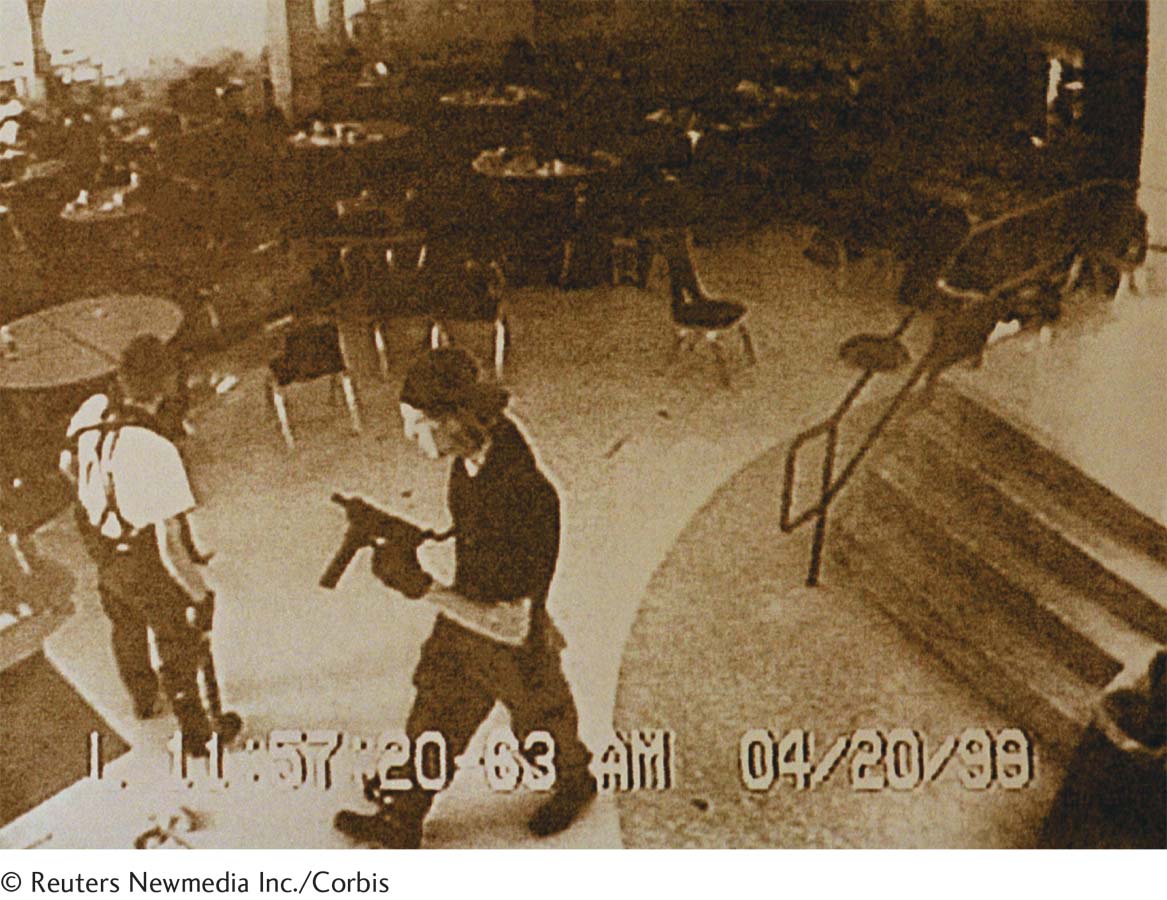

2003 For three weeks in October 2002, John Allen Muhammad and Lee Boyd Malvo went on a sniping spree in the Washington, DC, area, shooting 10 people dead and wounding 3 others. Attorneys for Malvo, a teenager, argued that he had acted under the influence of the middle-

2006 On June 20, 2001, Andrea Yates, a 36-

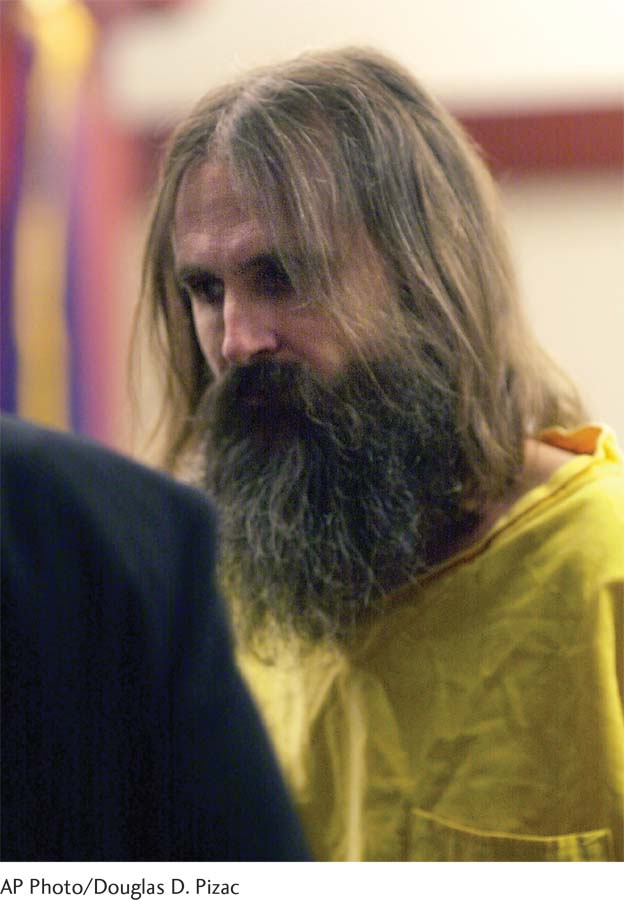

2011 In 2002, Brian David Mitchell abducted a 14-

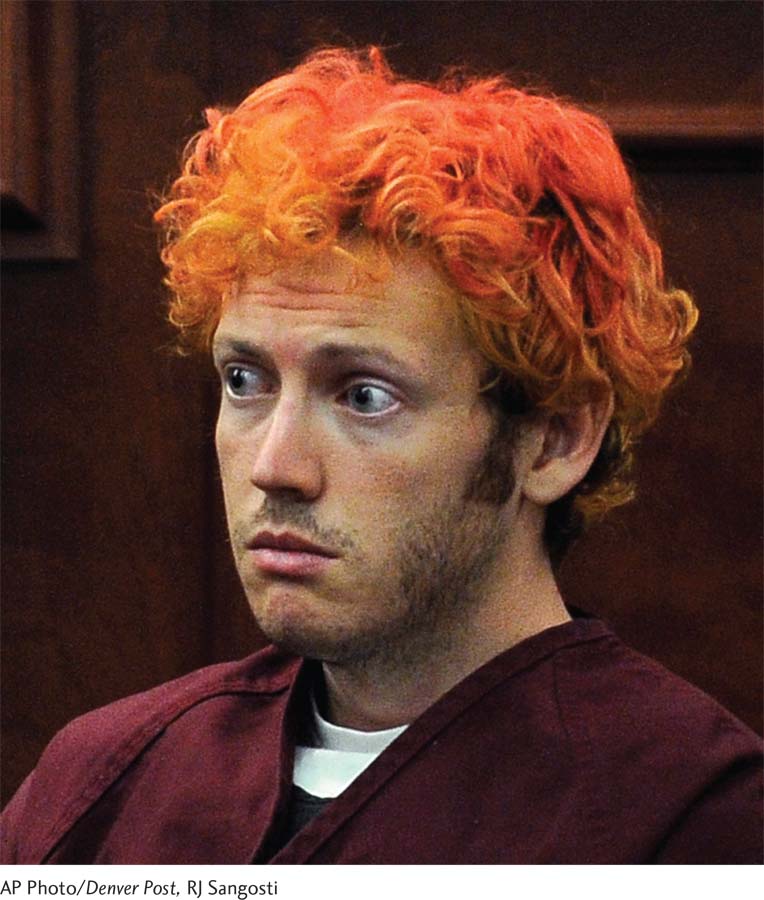

2012 On July 20, 2012, James Holmes, a 25-

During most of U.S. history, a successful insanity plea amounted to the equivalent of a long-

After patients have been criminally committed to institutions, why might clinicians be hesitant to later declare them unlikely to commit the same crime again?

Today, however, offenders are being released from mental hospitals earlier and earlier. This trend is the result of the increasing effectiveness of drug therapy and other treatments in institutions, the growing reaction against extended institutionalization, and more emphasis on patients’ rights (Slovenko, 2011, 2009, 2004). In 1992, in the case of Foucha v. Louisiana, the U.S. Supreme Court clarified that the only acceptable basis for determining the release of hospitalized offenders is whether or not they are still “insane”; they cannot be kept indefinitely in mental hospitals solely because they are dangerous. Some states are able to maintain control over offenders even after their release from hospitals. The states may insist on community treatment, monitor the patients closely, and rehospitalize them if necessary (Swanson & Swartz, 2014).

guilty but mentally ill A verdict stating that defendants are guilty of committing a crime but are also suffering from a mental illness that should be treated during their imprisonment.

WHAT OTHER VERDICTS ARE AVAILABLE? Over the past four decades, at least 20 states have added another verdict option—

After initial enthusiasm for this verdict option, legal and clinical theorists have increasingly found it unsatisfactory. According to research, it has not reduced the number of not guilty by reason of insanity verdicts, and it often confuses jurors (Bartol & Bartol, 2015). In addition, as critics point out, appropriate mental health care is supposed to be available to all prisoners anyway, regardless of the verdict. That is, the verdict of guilty but mentally ill may differ from a guilty verdict in name only.

Some states allow still another kind of defense, guilty with diminished capacity, in which a defendant’s mental dysfunctioning is viewed as an extenuating circumstance that the court should take into consideration in determining the precise crime of which he or she is guilty (Slovenko, 2011; Leong, 2000). The defense lawyer argues that because of mental dysfunctioning, the defendant could not have intended to commit a particular crime. The person can then be found guilty of a lesser crime—

Defense attorney Douglas Schmidt argued that a patriotic, civic-

Well known in forensic psychiatry circles, Martin Blinder, professor of law and psychiatry at the University of California’s Hastings Law School in San Francisco, brought a good measure of academic prestige to White’s defense. White had been, Blinder explained to the jury, “gorging himself on junk food: Twinkies, Coca-

Dan White was convicted only of voluntary manslaughter, and was sentenced to seven years, eight months. (He was released on parole January 6, 1984.) Psychiatric testimony convinced the jury that White did not wish to kill George Moscone or Harvey Milk.

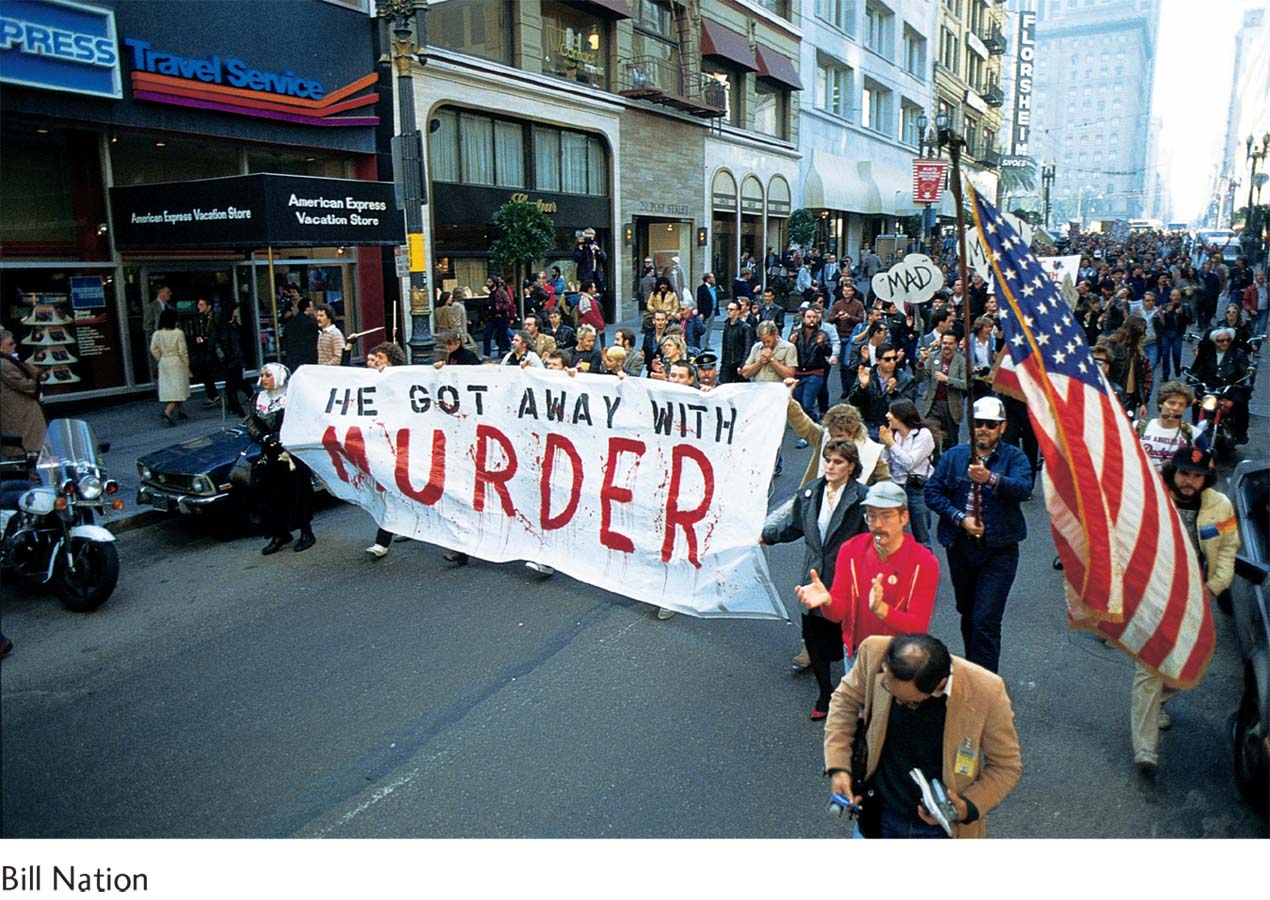

The angry crowd that responded to the verdict by marching, shouting, trashing City Hall, and burning police cars was in good part homosexual. Gay supervisor Harvey Milk had worked well for their cause, and his loss was a serious setback for human rights in San Francisco. Yet it was not only members of the gay community who were appalled at the outcome. Most San Franciscans shared their feelings of outrage.

BETWEEN THE LINES

The Aftermath

Convicted of voluntary manslaughter in 1979, Dan White was released from prison in 1984. He committed suicide in 1985.

(Coleman, 1984, pp. 65–

Because of possible miscarriages of justice, many legal experts have argued against the “diminished capacity” defense. A number of states have even eliminated it, including California shortly after the Dan White verdict (Gado, 2008).

WHAT ARE SEX-

People classified in this way are convicted of a criminal offense and are thus judged to be responsible for their actions. Nevertheless, mentally disordered sex offenders are sent to a mental health facility instead of a prison. In part, such laws reflect a belief held by many legislators that such sex offenders are psychologically disturbed. On a practical level, the laws help protect sex offenders from the physical abuse that they often receive in prison society.

Over the past two decades, however, most states have been changing or abolishing their mentally disordered sex offender laws, and at this point only a handful still have them. There are several reasons for this trend. First, the state laws often require that in order to be classified as a mentally disordered sex offender, the person must be a good candidate for treatment, a judgment that is difficult for clinicians to make for this population (Marshall et al., 2011). Second, there is evidence that racial bias often affects the use of the mentally disordered sex offender classification. From a defendant’s perspective, this classification is considered an attractive alternative to imprisonment—

But perhaps the primary reason that mentally disordered sex offender laws have lost favor is that state legislatures and courts are now less concerned than they used to be about the rights and needs of sex offenders, given the growing number of sex crimes taking place across the country (Laws & Ward, 2011), particularly ones in which children are victims. In fact, in response to public outrage over the high number of sex crimes, 21 states and the federal government have instead passed sexually violent predator laws (or sexually dangerous persons laws). These new laws call for certain sex offenders who have been convicted of sex crimes and have served their sentence in prison to be removed from prison before their release and committed involuntarily to a mental hospital for treatment if a court judges them likely to engage in further “predatory acts of sexual violence” as a result of “mental abnormality” or “personality disorder” (Perillo et al., 2014; Miller, 2010). That is, in contrast to the mentally disordered sex offender laws, which call for sex offenders to receive treatment instead of imprisonment, the sexually violent predator laws require certain sex offenders to receive imprisonment and then, in addition, be committed for a period of involuntary treatment. The constitutionality of the sexually violent predator laws was upheld by the Supreme Court in the 1997 case of Kansas v. Hendricks by a 5-

mental incompetence A state of mental instability that leaves defendants unable to understand the legal charges and proceedings they are facing and unable to prepare an adequate defense with their attorney.

Criminal Commitment and Incompetence to Stand Trial Regardless of their state of mind at the time of a crime, defendants may be judged to be mentally incompetent to stand trial. The competence requirement is meant to ensure that defendants understand the charges they are facing and can work with their lawyers to prepare and conduct an adequate defense (Ragatz et al., 2014; Reisner et al., 2013). This minimum standard of competence was specified by the Supreme Court in the case of Dusky v. United States (1960).

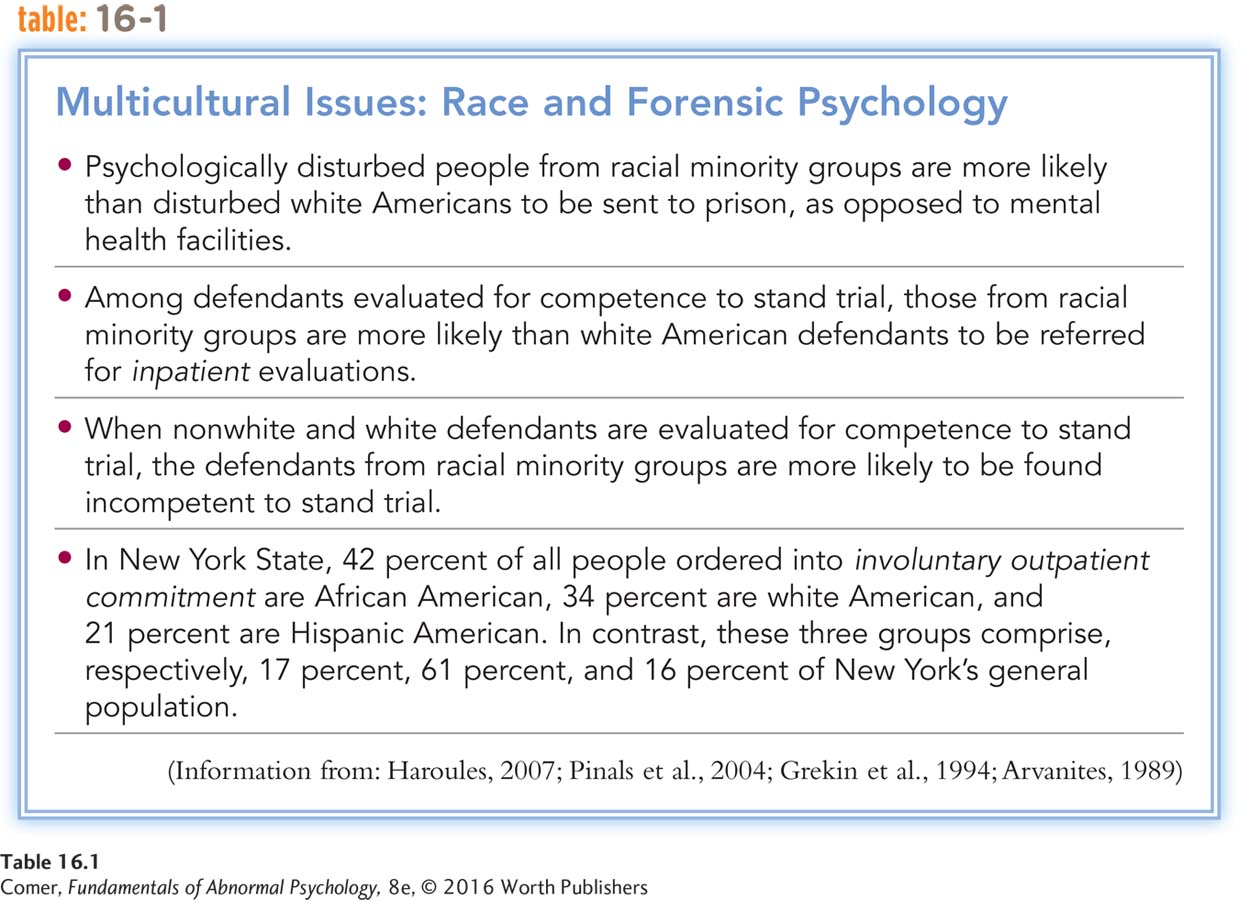

The issue of competence is most often raised by the defendant’s attorney, although prosecutors, arresting police officers, and even the judge may raise it as well (Reisner et al., 2013). When the issue of competence is raised, the judge orders a psychological evaluation, usually on an inpatient basis (see Table 16.1). As many as 60,000 competency evaluations are conducted in the United States each year (Bartol & Bartol, 2015). Approximately 20 percent of defendants who receive such an evaluation are found to be incompetent to stand trial. If the court decides that the defendant is incompetent, he or she is typically assigned to a mental health facility until competent to stand trial.

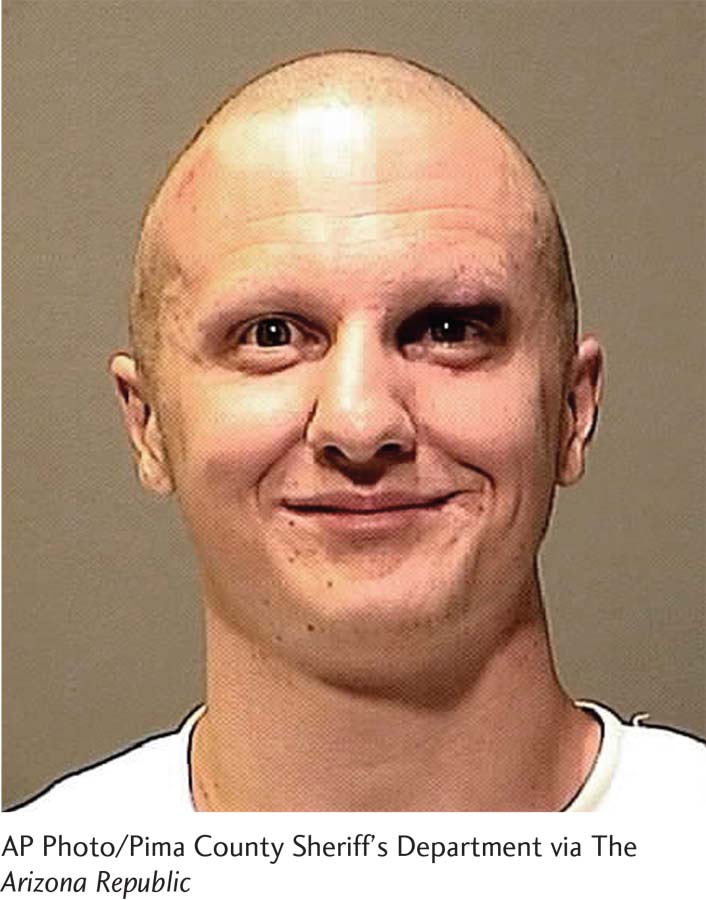

A famous case of incompetence to stand trial is that of Jared Lee Loughner. On January 8, 2011, Loughner went to a political gathering at a shopping center in Tucson, Arizona, and opened fire on 20 people. Six were killed and 14 injured, including U.S. representative Gabrielle Giffords. Giffords, the apparent target of the attack, survived, although she was shot in the head. After Loughner underwent five weeks of psychiatric assessment, a judge ruled that he was incompetent to stand trial. It was not until 18 months later, after extended treatment with antipsychotic drugs, that Loughner was ruled competent to stand trial. In November 2012, he pleaded guilty to murder and was sentenced to life imprisonment.

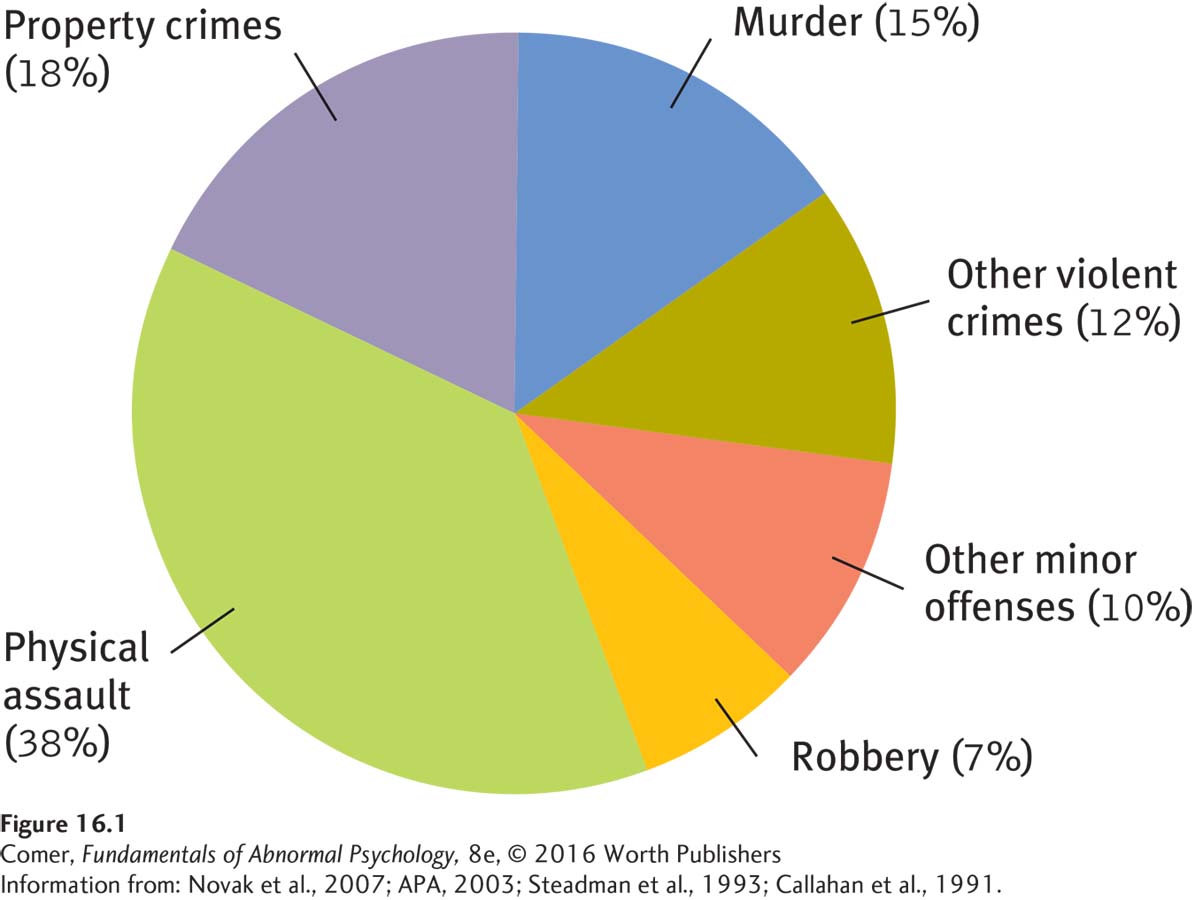

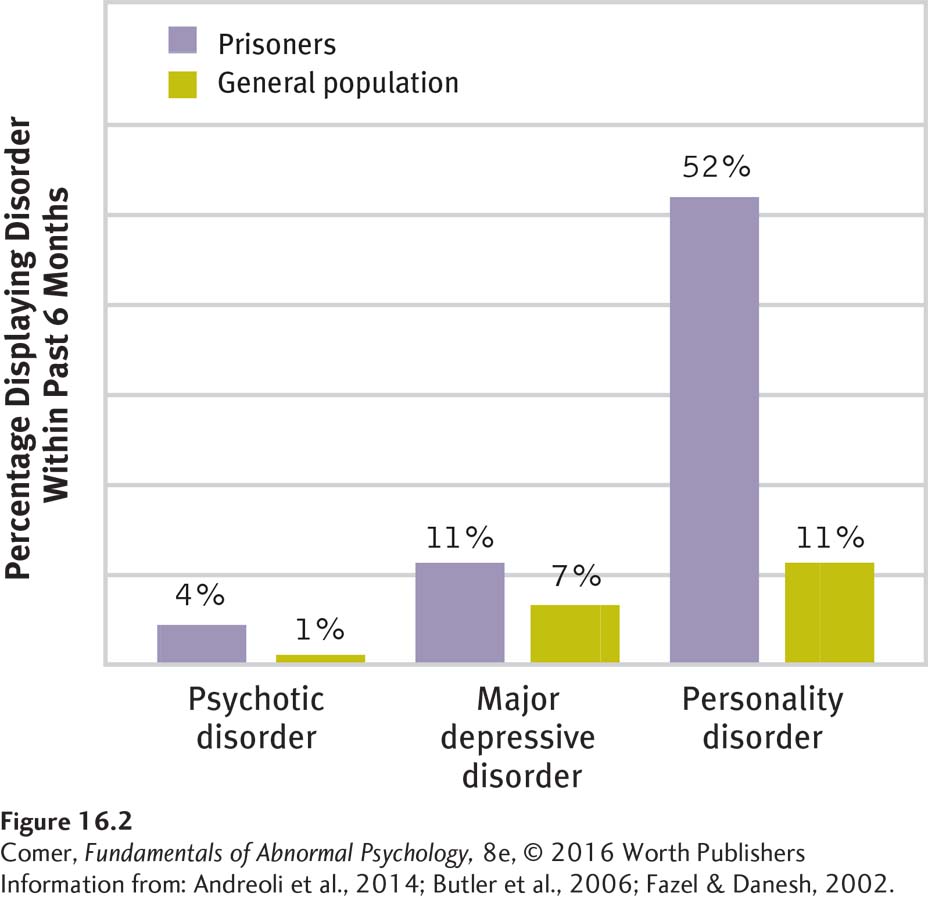

Many more cases of criminal commitment result from decisions of mental incompetence than from verdicts of not guilty by reason of insanity (Roesch et al., 2010). However, the majority of criminals currently institutionalized for psychological treatment in the United States are not from either of these two groups. Rather, they are convicted inmates whose psychological problems have led prison officials to decide they need treatment, either in mental health units within the prison or in mental hospitals (Metzner & Dvoskin, 2010) (see Figure 16.2).

It is possible that an innocent defendant, ruled incompetent to stand trial, could spend years in a mental health facility with no opportunity to disprove the criminal accusations against him or her. Some defendants have, in fact, served longer “sentences” in mental health facilities awaiting a ruling of competence than they would have served in prison had they been convicted. Such a possibility was reduced when the Supreme Court ruled, in the case of Jackson v. Indiana (1972), that an incompetent defendant cannot be indefinitely committed. After a reasonable amount of time, he or she should either be found competent and tried, set free, or transferred to a mental health facility under civil commitment procedures.

Until the early 1970s, most states required that mentally incompetent defendants be committed to maximum security institutions for the “criminally insane.” Under current law, however, the courts have more flexibility. In fact, when the charges are relatively minor, such defendants are often treated on an outpatient basis, an arrangement often called jail diversion because the disturbed person is “diverted” from jail to the community for mental health care (Hernandez, 2014).

Summing Up

HOW DO CLINICIANS INFLUENCE THE CRIMINAL JUSTICE SYSTEM? One of the ways in which the mental health profession interacts with the legislative and judicial systems is that clinicians may help assess the mental stability of people accused of crimes. Evaluations by clinicians may help judges and juries decide whether defendants are responsible for crimes or capable of defending themselves in court.

If defendants are judged to have been mentally unstable at the time they committed a crime, they may be found not guilty by reason of insanity and placed in a treatment facility rather than a prison. In federal courts and about half the state courts, insanity is judged in accordance with the M’Naghten test. Other states use the broader American Law Institute test.

The insanity defense has been criticized on several grounds, and some states have added an additional option, guilty but mentally ill. Another verdict option is guilty with diminished capacity. A related category consists of convicted sex offenders, who are considered in some states to have a mental disorder and are therefore assigned to treatment in a mental health facility.

Regardless of their state of mind at the time of the crime, defendants may be found mentally incompetent to stand trial, that is, incapable of fully understanding the charges or legal proceedings that confront them. These defendants are typically sent to a mental hospital until they are competent to stand trial.

How Do the Legislative and Judicial Systems Influence Mental Health Care?

civil commitment A legal process by which a person can be forced to undergo mental health treatment.

Just as clinical science and practice have influenced the legal system, so the legal system has had a major impact on clinical practice. First, courts and legislatures have developed the process of civil commitment, which allows certain people to be forced into mental health treatment. Although many people who show signs of mental disturbance seek treatment voluntarily, a large number are not aware of their problems or are simply not interested in undergoing therapy. For such people, civil commitment procedures may be put into action.

Second, the legal system, on behalf of the state, has taken on the responsibility of protecting patients’ rights during treatment. This protection extends not only to patients who have been involuntarily committed but also to those who seek treatment voluntarily, even on an outpatient basis.

Civil Commitment Every year in the United States, large numbers of people with mental disorders are involuntarily committed to treatment. Typically they are committed to mental institutions, but 45 states also have some form of outpatient civil commitment laws that allow patients to be forced into community treatment programs (Morrissey et al., 2014; Swanson & Swartz, 2014). Civil commitments have long caused considerable debate. In some ways the law provides more protection for people suspected of being criminals than for people suspected of being psychotic (Strachan, 2008; Burton, 1990).

BETWEEN THE LINES

In Their Words

“Our [legal] confusion is eliminated, we believe, if we resort to that quintessential twentieth-

(Winslade and Ross, 1983)

WHY COMMIT? Generally our legal system permits involuntary commitment of individuals when they are considered to be in need of treatment and dangerous to themselves or others. People may be dangerous to themselves if they are suicidal or if they act recklessly (for example, drinking a drain cleaner to prove that they are immune to its chemicals). They may be dangerous to others if they seek to harm them or if they unintentionally place others at risk. The state’s authority to commit disturbed people rests on its duties to protect the interests of the individual and of society.

WHAT ARE THE PROCEDURES FOR CIVIL COMMITMENT? Civil commitment laws vary from state to state. Some basic procedures, however, are common to most of these laws. Often family members begin commitment proceedings. In response to a son’s psychotic behavior and repeated assaults on other people, for example, his parents may try to persuade him to seek admission to a mental institution. If the son refuses, the parents may go to court and seek an involuntary commitment order. If the son is a minor, the process is simple. The Supreme Court has ruled that a hearing is not necessary in such cases, as long as a qualified mental health professional considers commitment necessary. If the son is an adult, however, the process is more involved. The court usually will order a mental examination and allow the person to contest the commitment in court, often represented by a lawyer.

The Supreme Court has ruled that before an individual can be committed, there must be “clear and convincing” proof that he or she is mentally ill and has met the state’s criteria for involuntary commitment. The ruling does not suggest what criteria should be used. That matter is still left to each state. But, whatever the state’s criteria, clinicians must offer clear and convincing proof that the person meets those criteria. When is proof clear and convincing, according to the court? When it provides 75 percent certainty that the criteria of commitment have been met. This is far less than the near-

EMERGENCY COMMITMENT Many situations require immediate action; no one can wait for commitment proceedings when a life is at stake. Consider, for example, an emergency patient who is suicidal or hearing voices demanding hostile actions against others. He or she may need immediate treatment and round-

Therefore, many states give clinicians the right to certify that certain patients need temporary commitment and medication. In past years, these states required certification by two physicians (not necessarily psychiatrists in some of the states). Today states may allow certification by other mental health professionals as well. The clinicians must declare that the state of mind of the patient makes them dangerous to themselves or others. By tradition, the certifications are often referred to as two-

WHO IS DANGEROUS? In the past, people with mental disorders were actually less likely than others to commit violent or dangerous acts. This low rate of violence was apparently related to the fact that so many such people lived in institutions. As a result of deinstitutionalization, however, hundreds of thousands of people with severe disturbances now live in the community, and many of them receive little, if any, treatment. Some are indeed dangerous to themselves or others.

Although approximately 90 percent of people with mental disorders are in no way violent or dangerous, studies now suggest at least a small relationship between severe mental disorders and violent behavior (Glied & Frank, 2014; Palijan et al., 2010). The disorders with the strongest relationships to violence are severe substance use disorder, impulse control disorder, antisocial personality disorder, and psychotic disorders (Ten Have et al., 2014; Volavka, 2013). Of these, substance use disorder appears to be the single most influential factor. For example, schizophrenia compounded by substance use disorder has a stronger relationship to violence than schizophrenia alone does.

A judgment of dangerousness is often required for involuntary civil commitment. But can mental health professionals accurately predict who will commit violent acts? Research suggests that psychiatrists and psychologists are wrong more often than right when they make long-

WHAT ARE THE PROBLEMS WITH CIVIL COMMITMENT? Civil commitment has been criticized on several grounds (Evans & Salekin, 2014; Falzer, 2011; Winick, 2008). First is the difficulty of assessing a person’s dangerousness. If judgments of dangerousness are often inaccurate, how can one justify using them to deprive people of liberty? Second, the legal definitions of “mental illness” and “dangerousness” are vague. The terms may be defined so broadly that they could be applied to almost anyone an evaluator views as undesirable. Indeed, many civil libertarians worry about involuntary commitment being used to control people, as was done in the former Soviet Union and now seems to be taking place in China, where mental hospitals house people with unpopular political views. A third problem is the sometimes questionable therapeutic value of civil commitment. Research suggests that many people committed involuntarily do not respond well to therapy.

BETWEEN THE LINES

Illusion of Knowledge

| 75% | Percentage of psychologists who are misinformed about their legal responsibilities regarding potentially dangerous clients. |

| 90% | Percentage of same psychologists who feel confident that their legal knowledge in this realm is accurate. |

(Thomas, 2014)

TRENDS IN CIVIL COMMITMENT The flexibility of the involuntary commitment laws probably reached a peak in 1962. That year, in the case of Robinson v. California, the Supreme Court ruled that imprisoning people who suffered from drug addiction might violate the Constitution’s ban on cruel and unusual punishment, and it recommended involuntary civil commitment to a mental hospital as a more reasonable action. This ruling encouraged the civil commitment of many kinds of “social deviants,” and many such individuals found it difficult to obtain release from the hospitals to which they were committed.

How are people who have been institutionalized viewed and treated by other people in society today?

During the late 1960s and early 1970s, reporters, novelists, civil libertarians, and others spoke out against the ease with which so many people were being unjustifiably committed to mental hospitals. As the public became more aware of these issues, state legislatures started to pass stricter standards about involuntary commitment (Pekkanen, 2007, 2002). Some states, for example, spelled out specific types of behavior that a person had to show before he or she could be determined to be dangerous. Rates of involuntary commitment then declined and release rates rose. Fewer people are institutionalized through civil commitment procedures today than in the past.

Protecting Patients’ Rights Over the past two decades, court decisions and state and federal laws have significantly expanded the rights of patients with mental disorders, in particular the right to treatment and the right to refuse treatment (Lepping & Raveesh, 2014).

right to treatment The legal right of patients, particularly those who are involuntarily committed, to receive adequate treatment.

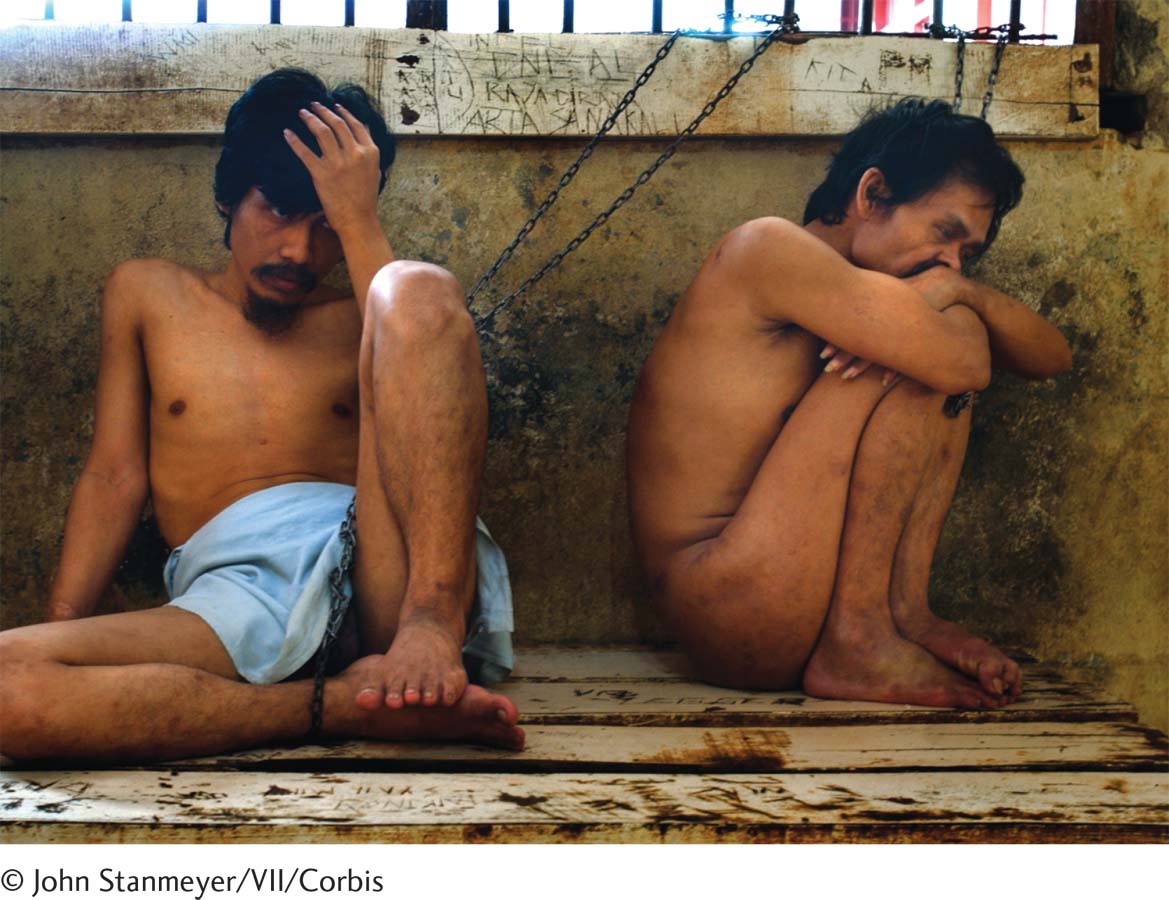

HOW IS THE RIGHT TO TREATMENT PROTECTED? When people are committed to mental institutions and do not receive treatment, the institutions become, in effect, prisons for the unconvicted. To many patients in the late 1960s and the 1970s, large state mental institutions were just that, and some patients and their attorneys began to demand that the state honor their right to treatment. In the landmark case of Wyatt v. Stickney, a suit on behalf of institutionalized patients in Alabama in 1972, a federal court ruled that the state was constitutionally obligated to provide “adequate treatment” to all people who had been committed involuntarily. Because conditions in the state’s hospitals were so terrible, the judge laid out goals that state officials had to meet, including more therapists, better living conditions, more privacy, more social interactions and physical exercise, and a more proper use of physical restraint and medication. Other states have since adopted many of these standards.

Another important decision was handed down in 1975 by the Supreme Court in the case of O’Connor v. Donaldson. After being held in a Florida mental institution for more than 14 years, Kenneth Donaldson sued for release. He argued that he and his fellow patients were receiving poor treatment, were being largely ignored by the staff, and were allowed little personal freedom. The Supreme Court ruled in his favor, fined the hospital’s superintendent, and said that such institutions must review patients’ cases periodically. The justices also ruled that the state cannot continue to institutionalize people against their will if they are not dangerous and are capable of surviving on their own or with the willing help of responsible family members or friends.

To help protect the rights of patients, Congress passed the Protection and Advocacy for Mentally Ill Individuals Act in 1986. This law set up protection and advocacy systems in all states and gave public advocates who worked for patients the power to investigate possible abuse and neglect and to correct those problems legally.

In recent years, public advocates have argued that the right to treatment also should be extended to the tens of thousands of people with severe mental disorders who are repeatedly released from hospitals into ill-

right to refuse treatment The legal right of patients to refuse certain forms of treatment.

HOW IS THE RIGHT TO REFUSE TREATMENT PROTECTED? During the past two decades, the courts have also decided that patients, particularly those in institutions, have the right to refuse treatment (Ford & Rotter, 2014; Perlin, 2004, 2000). Most of the right-

Some states have also acknowledged a patient’s right to refuse electroconvulsive therapy (ECT), the treatment used in many cases of severe depression (see Chapter 6). However, the right-

In the past, patients did not have the right to refuse psychotropic medications. As you have read, however, many psychotropic drugs are very powerful, and some produce effects that are unwanted and dangerous. As these harmful effects have become more apparent, some states have granted patients the right to refuse medication. Typically, these states require physicians to explain the purpose of the medication to patients and obtain their written consent. If a patient’s refusal is considered incompetent, dangerous, or irrational, the state may allow it to be overturned by an independent psychiatrist, medical committee, or local court. However, the refusing patient is supported in this process by a lawyer or other patient advocate.

WHAT OTHER RIGHTS DO PATIENTS HAVE? Court decisions have protected still other patient rights over the past several decades. Patients who perform work in mental institutions, particularly private institutions, are now guaranteed at least a minimum wage. In addition, according to a court decision, patients released from state mental hospitals have a right to aftercare and to an appropriate community residence, such as a group home. And more generally, people with psychological disorders should receive treatment in the least restrictive facility available. If an inpatient program at a community mental health center is available and appropriate, for example, then that is the facility to which they should be assigned, not a mental hospital.

THE “RIGHTS” DEBATE Certainly, people with psychological disorders have civil rights that must be protected at all times. However, many clinicians express concern that the patients’ rights rulings and laws may unintentionally deprive these patients of opportunities for recovery. Consider the right to refuse medication. If medications can help a patient with a severe mental disorder to recover, doesn’t the patient have the right to that recovery? If confusion causes the patient to refuse medication, can clinicians in good conscience delay medication while legal channels are cleared?

Despite such legitimate concerns, keep in mind that the clinical field has not always done an effective job of protecting patients’ rights. Over the years, many patients have been overmedicated and received improper treatments. Furthermore, one must ask whether the field’s present state of knowledge justifies clinicians’ overriding of patients’ rights. Can clinicians confidently say that a given treatment will help a patient? Can they predict when a treatment will have harmful effects? Since clinicians themselves often disagree, it seems appropriate for patients, their advocates, and outside evaluators to also play key roles in decision making.

Summing Up

HOW DOES THE LEGAL SYSTEM INFLUENCE MENTAL HEALTH CARE? Courts may be called upon to commit noncriminals to mental hospitals for treatment, a process called civil commitment. Society allows such involuntary commitment for people considered to be in need of treatment and dangerous to themselves or others. Laws and criteria governing civil commitment procedures vary from state to state, but the Supreme Court has ruled that, whatever the state’s criteria, clinicians must offer clear and convincing evidence that the individuals are mentally ill and meet the state’s criteria for civil commitment.

The courts and legislatures also affect the mental health profession by specifying legal rights to which patients are entitled. The rights that have received the most attention are the right to treatment and the right to refuse treatment.

In What Other Ways Do the Clinical and Legal Fields Interact?

Mental health and legal professionals may influence each other’s work in other ways as well. During the past 25 years, their paths have crossed in four key areas: malpractice suits, professional boundaries, jury selection, and psychological research of legal topics.

malpractice suit A lawsuit charging a therapist with improper conduct in the course of treatment.

Malpractice Suits The number of malpractice suits against therapists has risen sharply in recent years. Claims have been made against clinicians in response to a patient’s attempted suicide, sexual activity with a patient, failure to obtain informed consent for a treatment, negligent drug therapy, omission of drug therapy that would speed improvement, improper termination of treatment, and wrongful commitment (Sher, 2015; Reich & Schatzberg, 2014). Studies suggest that malpractice suits, or the fear of them, can have significant effects on clinical decisions and practice, for better or for worse (Appelbaum, 2011; Feldman et al., 2005).

Professional Boundaries Over the past two decades, the legislative and judicial systems have helped to change the boundaries that distinguish one clinical profession from another. In particular, they have given more authority to psychologists and blurred the lines that once separated psychiatry from psychology. A growing number of states, for example, are ruling that psychologists can admit patients to the state’s hospitals, a power previously held only by psychiatrists.

Most psychiatrists oppose the idea of prescription rights for psychologists. Why do some psychologists also oppose this idea?

In 1991, with the blessing of Congress, the Department of Defense (DOD) started to reconsider the biggest difference of all between the practices of psychiatrists and psychologists—

Jury Selection During the past 30 years, more and more lawyers have turned to clinicians for psychological advice in conducting trials (Crouter, 2015; Hope, 2010). A new breed of clinical specialists, known as “jury specialists,” has evolved. They advise lawyers about which potential jurors are likely to favor their side and which strategies are likely to win jurors’ support during trials. The jury specialists make their suggestions on the basis of surveys, interviews, analyses of jurors’ backgrounds and attitudes, and laboratory enactments of upcoming trials. However, it is not clear that a clinician’s advice is more valid than a lawyer’s instincts or that the judgments of either are particularly accurate.

Psychological Research of Legal Topics Psychologists have sometimes conducted studies and developed expertise on topics of great importance to the criminal justice system. In turn, these studies influence how the system carries out its work. Psychological investigations of two topics, eyewitness testimony and patterns of criminality, have gained particular attention.

EYEWITNESS TESTIMONY In criminal cases, testimony by eyewitnesses is extremely influential. It often determines whether a defendant will be found guilty or not guilty. But how accurate is eyewitness testimony? This question has become urgent, as a troubling number of prisoners (many on death row) have had their convictions overturned after DNA evidence revealed that they could not have committed the crimes of which they had been convicted. It turns out that more than 75 percent of such wrongful convictions were based in large part on mistaken eyewitness testimony (Wise et al., 2014).

Most eyewitnesses undoubtedly try to tell the truth about what or who they saw. Yet research indicates that eyewitness testimony can be highly unreliable, partly because most crimes are unexpected and fleeting and therefore not the sort of events remembered well (Houston et al., 2013). During the crime, for example, lighting may be poor or other distractions may be present. Witnesses may have had other things on their minds, such as concern for their own safety or that of bystanders. Such concerns may greatly impair later memory.

In laboratory studies, researchers have found it easy to fool research participants who are trying to recall the details of an observed event simply by introducing misinformation (Morgan et al., 2013; Laney & Loftus, 2010). After a suggestive description by the researcher, stop signs can be transformed into yield signs, white cars into blue ones, and Mickey Mouse into Minnie Mouse (Pickel, 2004; Loftus, 2003). In addition, laboratory studies indicate that persons who are highly suggestible have the poorest recall of observed events (Liebman et al., 2002).

As for identifying actual perpetrators, research has found that accuracy is heavily influenced by the method used in identification (Bartol & Bartol, 2015; Garrett, 2011). The traditional police lineup, for example, is not always a highly reliable technique, and the errors that witnesses make when looking at lineups tend to stick (Wells et al., 2015, 2011; Wells, 2008). Researchers have also learned that witnesses’ confidence is not necessarily related to accuracy (Wise et al., 2014; Ghetti et al., 2004). Witnesses who are “absolutely certain” may be no more correct in their recollections than those who are only “fairly sure.” Yet the degree of a witness’s confidence often influences whether jurors believe his or her testimony.

BETWEEN THE LINES

Popular TV Series Featuring Psychological Profilers

Criminal Minds

NCIS

The Mentalist

Law and Order: Special Victims Unit

Law and Order: Criminal Intent

Psychological investigations into the memories of eyewitnesses have not yet undone the judicial system’s reliance on or respect for those witnesses’ testimony. Nor should it. The distance between laboratory studies and real-

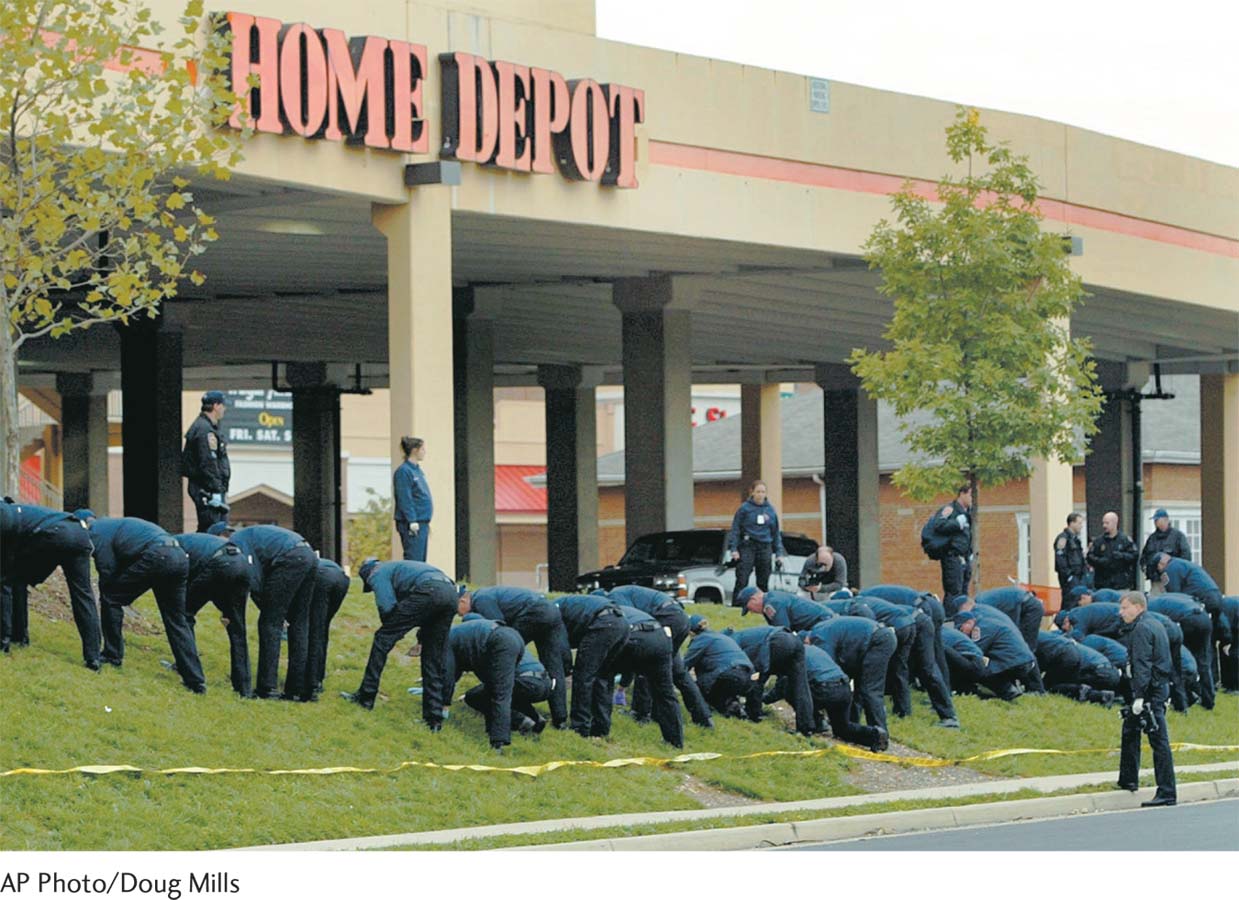

PATTERNS OF CRIMINALITY A growing number of television shows, movies, and books suggest that clinicians often play a major role in criminal investigations by providing police with psychological profiles of perpetrators—

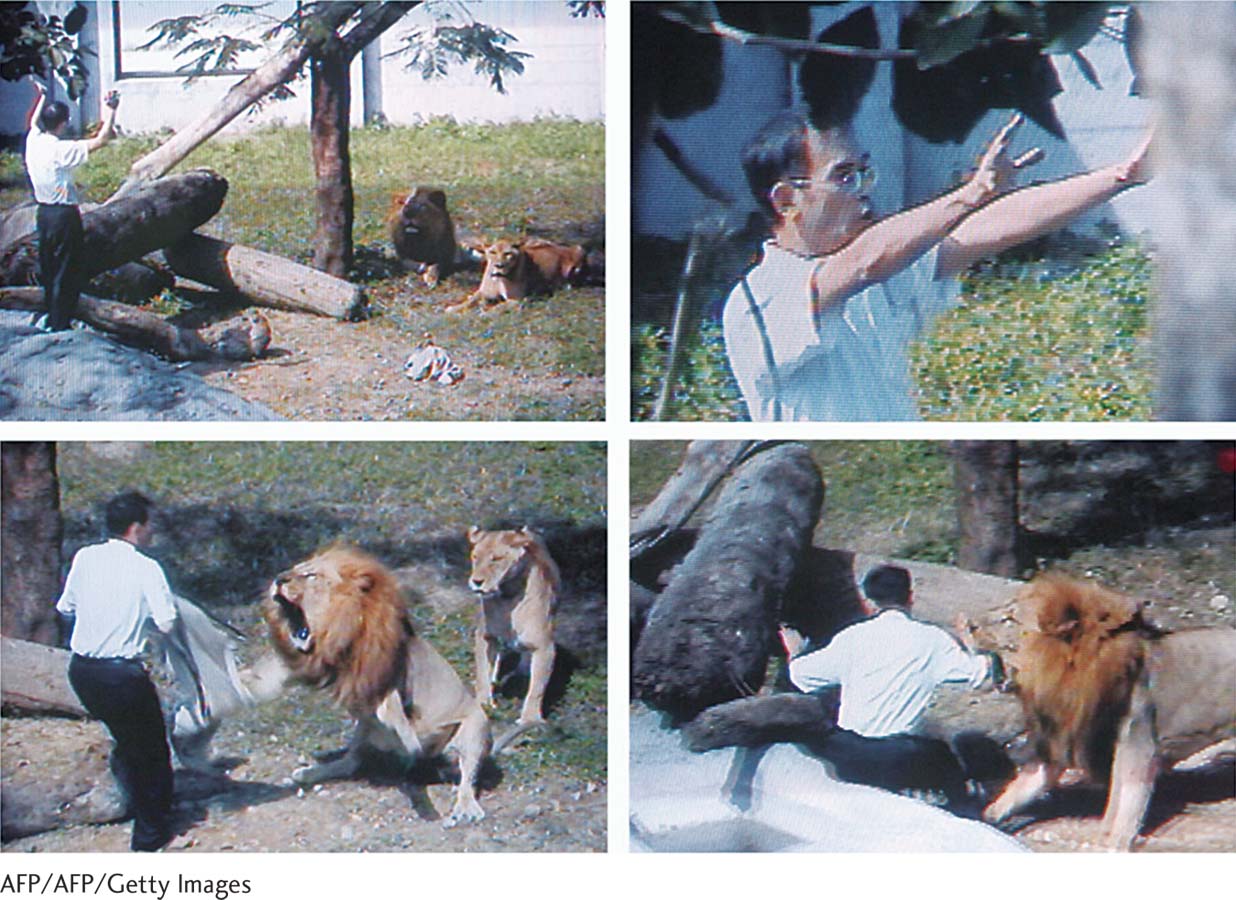

On the positive side, researchers have gathered information about the psychological features of various criminals, and they have indeed found that perpetrators of particular kinds of crimes—

A reminder of the limitations of profiling comes from the case of the snipers who terrorized the Washington, DC, area for three weeks in October 2002, shooting 10 people dead and seriously wounding 3 others. Most of the profiling done by FBI psychologists had suggested that the sniper was acting alone; it turned out that the attacks were conducted by a pair: a middle-

PsychWatch

Serial Murderers: Madness or Badness?

In late 2001, a number of anthrax-

Although Ivins’ suicide left behind unanswered questions, the FBI has concluded that this troubled man was indeed the anthrax killer. He appears to have been one of a growing list of serial killers who have fascinated and horrified Americans over the years: Theodore Kaczynski (“Unabomber”), Ted Bundy, David Berkowitz (“Son of Sam”), Albert DeSalvo, John Wayne Gacy, Jeffrey Dahmer, John Allen Muhammad, Lee Boyd Malvo, Dennis Rader (“BTK killer”), and more.

The FBI estimates that there are between 35 and 100 serial killers at large in the United States at any given time (FBI, 2014). Worldwide, 3,900 such killers have been identified since the year 1900 (Aamodt, 2014).

Each serial killer follows his or her own pattern, but many of them appear to have certain characteristics in common (Hickey, 2015; FBI, 2014; Fox & Levin, 2014). Most—

A number of serial killers seem to display severe personality disorders (Hickey, 2015; Dogra et al., 2012; Waller, 2010). Lack of conscience and an utter disregard for people and the rules of society—

Sexual dysfunction and fantasy also seem to play a part (FBI, 2014; Arndt et al., 2004). Studies have found that vivid fantasies, often sexual and sadistic, may help drive the killer’s behavior (Homant & Kennedy, 2006). Some clinicians also believe that the killers may be trying to overcome general feelings of powerlessness by controlling, hurting, or eliminating those who are momentarily weaker (Fox & Levin, 2014). A number of the killers were abused as children—

Despite such profiles and suspicions, clinical theorists do not yet understand why serial killers behave as they do. But most agree with Park Dietz, a highly regarded forensic expert, when he asserts, “It’s hard to imagine any circumstance under which they should be released to the public again” (Douglas, 1996, p. 349).

Summing Up

OTHER CLINICAL–