16.4 Technology and Mental Health

Technology is always changing and, like most other fields, the mental health field must work hard to keep pace with that change. This is not a new state of affairs. Technological change occurred 25, 50, 100 years ago and beyond. What is new, however, is the remarkable rate of technological change in the world today. As you have seen throughout this book, the digital and hyperconnected world in which we now live has had significant effects—

Consider for a moment the nature and breadth of technological change in today’s world. Around 3.1 billion people across the world currently use the Internet—

Video games have emerged as yet another force in our digital society. Sixty percent of Americans play such games on computers, cell phones, or consoles (ESA, 2015). Often gaming is a social experience: more than half of gamers play with other individuals in person, and some interact online with numerous other players in virtual game environments called MMOGs (Massively Multiplayer Online Games).

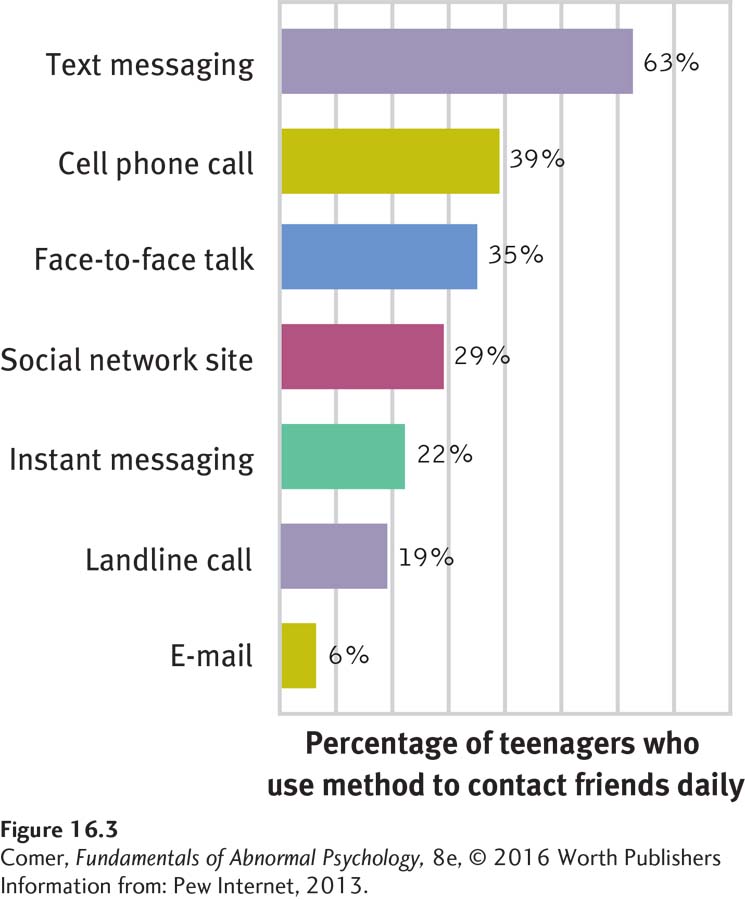

Finally, there is the spectacular growth of social networking among people of all ages. The number of social network users (on Facebook, Twitter, Pinterest, Tumblr, Instagram, and other such sites) is currently more than 2 billion worldwide and is continuing to rise (eBizMBA, 2015; Statista, 2015). Consider, for example, the remarkable growth of Twitter, the online social networking and micro-

MindTech

New Ethics for a Digital Age

New Ethics for a Digital Age

The American Psychological Association’s code of ethics states that psychologists who operate on the Internet (offer cybertherapy, for example) are bound by the same ethical requirements as those who operate more conventionally. That seems reasonable enough, except for one thing: operating online opens up a world of brand-

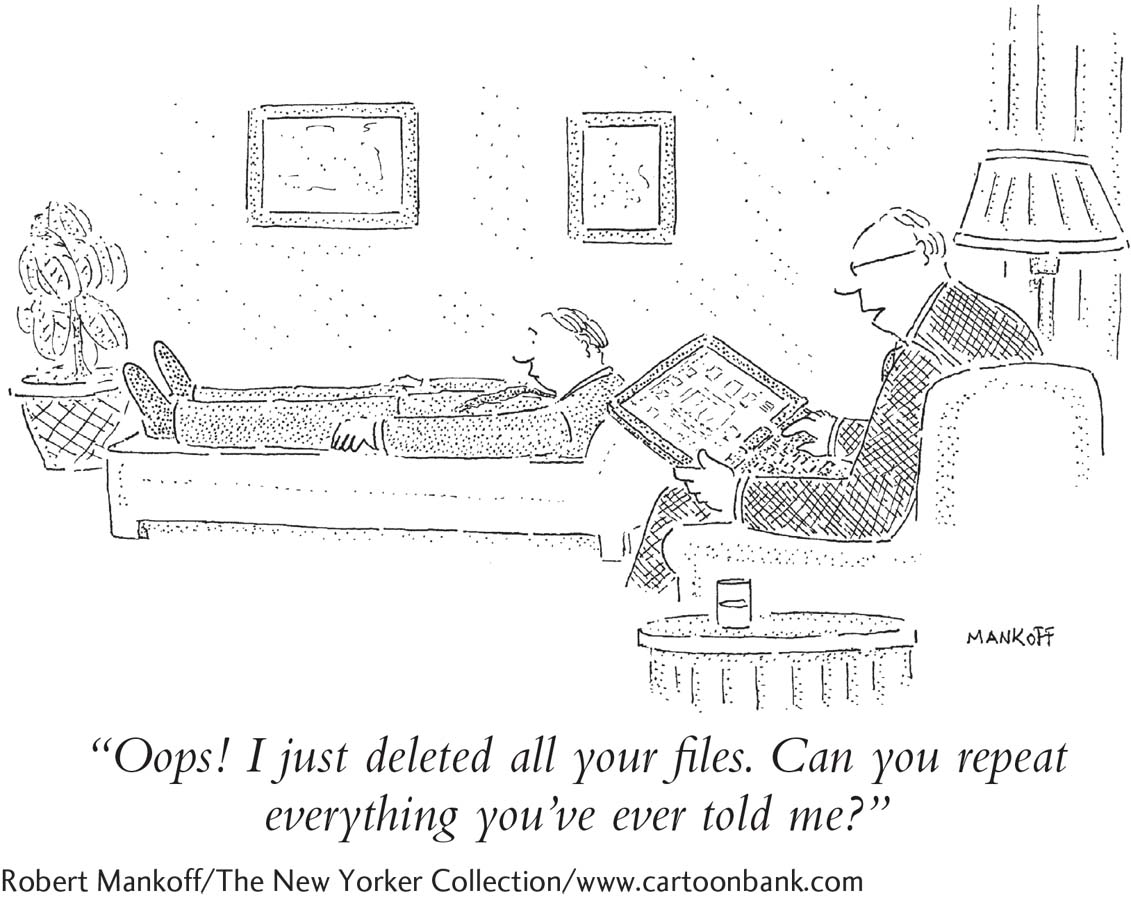

Two leading clinical theorists, Kenneth Pope and Danny Wedding (2014), have spent the last decade compiling a list of ethical dilemmas and nightmares that can emerge as a by-

Many therapists believe that because they do not conduct cybertherapy, they are untouched by digital concerns. Yet those same therapists likely use computers to keep notes of therapy sessions, maintain client billing information, score psychological tests, and the like. Thus, they might be alarmed to know that the following breaches of privacy have occurred more than a few times (Pope & Wedding, 2014):

A laptop containing confidential patient information is hacked or is stolen from an office or car trunk.

A virus, worm, or other kind of malware infects a therapist’s computer and uploads confidential files to a Web site or to everyone listed in his or her address book.

Someone reads a therapist’s laptop monitor—

and obtains confidential information— while sitting next to the therapist in an airport or on a flight. A therapist e-

mails a message containing confidential client information to a colleague, but accidentally sends it to the wrong e- mail address. A therapist sells a computer, not realizing that confidential information is still recoverable because a truly thorough form of scrubbing was not used.

What other ethical problems might emerge as a result of the mental health field’s increasing use of new technologies?

The digital age in which therapists treat clients presents many new ethical concerns and potential problems. Certainly, the field’s code of ethics must address these issues sooner rather than later. So too must each individual therapist. As Pope and Wedding (2014) point out, “When we use digital devices to handle the most sensitive and private information about our clients, we must remember to live up to an ancient precept: First, do no harm.”

Given these changes and trends in technology, it is not surprising that the focus, tools, and research directions of the mental health field have themselves expanded over the past decade. As you have observed throughout this book, for example, our digital world provides new triggers for the expression of abnormal behavior: Internet gambling has intensified the problem of gambling disorder (see pages 342–

Similarly, our fast-

Clearly, the growing impact of technological change on the mental health field presents significant challenges. Few of the technological applications discussed throughout this book are well understood, and few have been subjected to comprehensive research. Yet the relationship between technology and mental health is expected to expand still further in the coming years. It behooves everyone in the field to understand and be ready for this growth and its implications.