The Questions

The Questions

Page 367

Once you have set the stage for the interview with an appropriate opening, you need to develop the organizational plan for the body of the interview using questions and answers. The interviewer sets up the structure of the interview (identifying the purpose of the interview) and then solicits a response from the interviewee. This response then prompts reactions from the interviewer, and it just keeps building from there. To have the most effective and most successful interview possible, whether you’re the interviewer or interviewee, you need to consider question type, impact, and sequence.

Types of Questions. The path of the interview is largely determined by the types of questions asked. Questions vary in two distinct ways: the amount of freedom the respondent has and how the questions relate to what has happened in the course of the interview.

First, questions vary in terms of how much leeway the interviewee has in generating responses. An open question gives the interviewee great freedom in terms of how to respond. Questions like “What’s it like being a student here?” and “What issues will influence your decision to vote for one of the presidential candidates?” allow the interviewee to determine the amount and depth of information provided. Interviewers often ask open questions when the interviewee knows more about a topic than the interviewer does or to help the interviewee relax (there is no “correct” answer, so no answer is wrong).

In other situations, the interviewer will want a more direct answer. Closed questions give less freedom to the interviewee by restricting answer choices. For example, an interviewer conducting a survey of student attitudes toward parking on campus might ask more closed questions (“When do you arrive on campus?” “Where do you park?” “How long do you stay?”). The most closed form of a question is the bipolar question, for which there are only two possible responses, “yes” and “no” (“Do you normally eat breakfast?” “Do you own a car?” “Did you vote in the last election?”). Another possibility is to ask interviewees to respond on a scale, as with the question “How would you rate parking availability on campus on a scale of one to five?”

Questions also vary in terms of how they relate to what has happened so far in the interview. Primary questions introduce new topics; secondary questions seek clarification or elaboration of responses to primary questions. Thus, if you were interviewing an older family member, you might open an area of questioning by asking, “What can you tell me about my family history?” This primary question might then be followed by a number of secondary questions, such as “How did my grandparents meet?” and “How did they deal with the fact that their parents disapproved of their marriage?” Secondary questions can take a variety of forms. Some of the more common forms are illustrated in Table A.2.

| Table A.2 Secondary Questions | ||

| Behavior | Definition | Example |

| Clarification | Directly requests more information about a response | “Could you tell me a little more about the reasons you chose to join the military after high school?” |

| Elaboration | Directly requests an extension of a response | “Are there any other specific features that you consider important in your search for a new house?” |

| Paraphrasing | Puts the response in the questioner’s language in an attempt to establish understanding | “So, you’re saying that the type of people you work with is more important to you than location?” |

| Encouragement | Uses brief sounds and phrases that indicate attentiveness to and interest in what the respondent is saying | “Uh-huh,” “I see,” “That’s interesting,” “Good,” “Yes, I understand.” |

| Summarizing | Summarizes several previous responses and seeks confirmation of the correctness of the summary | “Let’s see if I’ve got it: your ideal job involves an appreciative boss, supportive colleagues, interesting work, and a location in a large metropolitan area?” |

| Clearinghouse | Asks if you have elicited all the important or available information | “Have I asked everything that I should have asked?” |

Source: Labels and definitions from O’Hair, Friedrich, & Dixon (2007).

Question Impact. In addition to considering question type, interviewers must also consider the likely impact of a question on the interviewee. The way in which a question is constructed can directly influence the information received in response. A good question is clear, relevant, and unbiased. To create clear questions, consider the following criteria:

- Make questions understandable. Ask the classic and simple news reporter’s questions—who, what, when, where, why, and how—before you proceed to more complex ones (Payne, 1951).

- Ensure that the wording of the questions is as direct and simple as possible. For example, asking “For whom did you vote in the last mayoral election?” will get you a more precise answer than asking “How do you vote?”

- Keep the questions short and to the point.

- Phrase questions positively and remain civil (Ben-Porath, 2010). For example, asking “Have you ever voted in campus student government elections?” is clear and objective; using negative phrasing (“You haven’t ever voted in the campus student government elections, have you?”) can be confusing and, in some cases, may be unethical and biased (Doris, 1991).

Ethics and You

Have you ever been asked unethical, biased, or uncivil questions in an interview? Did you ever, knowingly or unknowingly, ask these types of questions yourself? How can you deal with questions like these if you find yourself in that uncomfortable position?

Speaking of ethics, a question that suggests or implies the answer that is expected is called a directed question. Some directed questions are subtle in the direction they provide (“Wouldn’t it be so much fun if we all got together to paint my apartment this weekend?”). These subtle directed questions are leading questions. Other directed questions are bolder in their biasing effect and are called loaded questions (“When was the last time you cheated on an exam?” which assumes, of course, that you have cheated). Questions that provide no hint to the interviewee concerning the expected response are neutral questions—for example, “What, if anything, is your attitude toward the fraternities and sororities on this campus?”

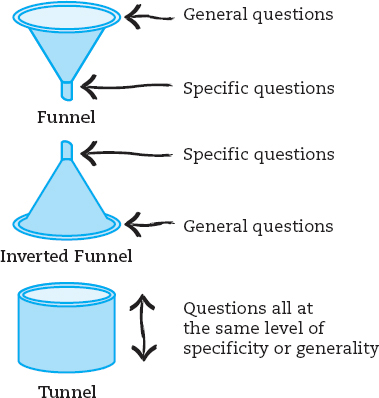

Question Sequence. The order in which the interviewer asks questions can affect both the accomplishment of the interview’s goals and the comfort level of the interviewee. There are three main “shapes” that guide the ordering of questions: the funnel, inverted funnel, and tunnel sequences.

In the funnel sequence, the interviewer starts with broad, open-ended questions (picture the big end of a funnel) and moves to narrower, more closed questions. The questions become more personal or more tightly focused as the interview progresses, giving the interviewee a chance to get comfortable with the topic and open up. The funnel sequence works best with respondents who feel comfortable with the topic and the interviewer.

- What do you think about children playing competitive sports? (general)

- So what disadvantages have you witnessed? (specific)

- What constraints would you advocate for young players? (very specific)

The inverted funnel sequence starts with narrow, closed questions and moves to more open-ended questions. The inverted funnel works best with interviewees who are emotional, reticent, or need help “warming up.”

- Did you perform a Mozart piece for your piano recital in junior high school? (very specific)

- What other classical compositions are you comfortable playing? (specific)

- How did you feel about taking piano lessons as a child? (general)

In the tunnel sequence, all the questions are at one level. The tunnel sequence works particularly well in polls and surveys. A large tunnel would involve a series of broad, open-ended questions. A small tunnel (the more common form) would ask a series of narrow, closed questions, as in the following example:

- Have you attended any multicultural events on campus? (specific)

- Have you attended sports games or matches? (specific)

- Have you attended any guest lecturer series on campus? (specific)

The three sequences are depicted visually in Figure A.1.

Interviewers can put together the three sequences in various combinations over the course of an interview based on the goals for the interview, the direction the interview takes, and the comfort level of both parties involved.

THINGS TO TRY

Observe a press conference on television. Who is being interviewed? Who is conducting the interview? What is the goal of the press conference? How is control distributed? List five questions that are asked, and label them according to the types listed in this chapter (open, closed, bipolar, primary, secondary). Did the questioning involve a particular sequence (funnel, inverted funnel, tunnel)? What did you learn about this interview format by answering these questions?