Make It Easy

Make It Easy

Page 320

Creating a good informative speech is hard work; listening to one should not be. Your job as a speaker is to find and distill a lot of information in a way that is easy for your audience to listen to, absorb, and learn. In short, you need to do your listeners’ work for them. To this end, there are a number of objectives to bear in mind as you prepare your speech, which we will now discuss.

Choose a Clear Organization and Structure. People have orderly minds. When they are presented with new information, they need to organize it in a way that makes sense to them. You can help them in this endeavor by organizing your speech around a clear and logical structure. Recall from chapter 12 that there are a number of arrangements for presentations, including chronological, topical, and spatial organizations; problem-solution, cause-effect, and narrative patterns; and arrangements based on motivated sequences. Your choice of organizational pattern will depend on your topic, and every speech will have several organizational options.

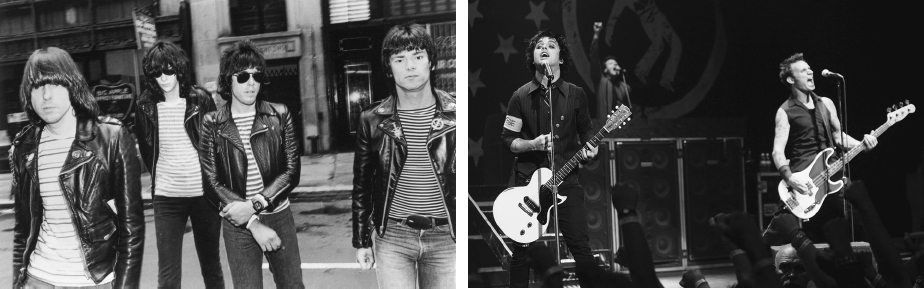

For example, if you’re planning to deliver a speech on the history of punk rock, you might choose a chronological organization, beginning with mid-1960s garage bands and following through the 1970s peak with bands like the Sex Pistols and the Ramones, through the post-punk era, and ending with modern punk-influenced bands like Green Day and the Libertines. But you might find it more interesting to approach the topic spatially, noting differences between American and British punk, or even causally, demonstrating how the form arose as a reaction to the popular music that preceded it as well as the economic and political climate of the times. Table 14.2, below, offers some ideas for using organizational approaches for different informative topics, in addition to considering the approaches we discussed earlier (definition, description, demonstration, and explanation).

| Table 14.2 Types of Informative Speeches, Sample Topics, Informational Strategies, and Organizational Patterns | |||

| Subject Matter | Sample Topics | Informational Strategy (definition, description, demonstration, explanation) | Suggested Organizational Patterns |

| Speeches about objects or phenomena |

|

Define and describe the object or phenomenon in question. Depending on your specific speech purpose, either conclude at that point or continue with an in-depth explanation or a demonstration of the object or phenomenon. | You might use a spatial pattern if you are explaining how a geographic positioning system (GPS) works in cars. Other useful patterns include topical, problem-solution, and cause-effect. |

| Speeches about people |

|

Paint a vivid picture of your subject using description. Use explanation to address the person’s or group’s significance. | Narrative patterns could be useful for speeches about people since stories can include rich details about a person’s life. Other useful patterns include motivated sequence and chronological. |

| Speeches about events |

|

Use description to paint a vivid picture. Use explanation to analyze the meaning of the event. | You might use a chronological pattern for a topic focusing on events if time or sequence is relevant to your purpose. Other useful patterns include motivated sequence, problem-solution, and spatial. |

| Speeches about processes |

|

If physically showing a process, rely on demonstration. If explaining a process, vary strategies as needed. | Cause-effect patterns of speech organization are helpful in explaining processes of various kinds. Additional patterns of organization could include spatial, problem-solution, or chronological. |

| Speeches about issues |

|

Focus on description and explanation. | Problem-solution is a strong choice for organizing speeches about issues. Other helpful patterns for issues include topical, spatial, and cause-effect. |

| Speeches about concepts |

|

Focus on clear definitions and explanations; the more difficult a concept is, the more ways you will want to define and explain it. Vivid description can also be useful. | Consider topical organizational patterns for speeches about concepts, as well as the narrative pattern. Other patterns that might work well include spatial and problem-solution. |

Source: O’Hair, Stewart, & Rubenstein (2007), p. 23. Adapted with permission.

Emphasize Important Points. Another way to make it easier for your audience to follow and absorb your speech is to clarify what the important parts are. As you learned in chapter 12, one of the best means to achieve this is by using a preview device and a concluding summary. The preview device tells the audience what you are going to cover (“First, I will discuss X, second, Y, and third, Z”). A concluding summary reviews what the audience heard during the speech (“Today, I talked about X, then showed you Y, and finally, discussed Z”).

Careful and deliberate use of phrases like “The key issue here is . . .” and “I have three main points regarding this piece of legislation” can also signal to your audience that you’re about to say something important. In some cases, you might actually highlight what is important by saying so, even telling the audience directly when you’re discussing something you want them to remember. This not only supports the organization of your speech but also gives people useful tools for organizing the information as they listen. It’s important to make certain, however, that you don’t contradict yourself. If you say, “I have one key point to make” and then list four points of equal importance, you will likely confuse (and annoy) your audience.

Don’t Overwhelm Your Audience. Have you ever sat through a lecture or a presentation in which the speaker seemed to give far too much information? Ironically, too many points can make a speech seem pointless, and an overabundance of facts and statistics can make it difficult to follow and impossible to retain. Research shows that message receivers’ attention and interest levels drop significantly due to information overload. Simply put, too much information overwhelms the audience (Van Zandt, 2004).

Ironically, too many points can make a speech seem pointless, and an overabundance of facts and statistics can make it difficult to follow and impossible to retain.

Your goal, then, is to keep your presentation as simple as possible so that audiences will find it easy to follow. As you review and rehearse your speech, critically evaluate each and every fact, point, example—indeed, every word—to make certain that it makes a real contribution. Eliminate anything redundant or tangential. You want to strike a perfect balance by telling your listeners just what they need to know to understand your topic—nothing more, nothing less.

Build on Prior Knowledge. Another way to make your speech easier to listen to and retain is to introduce new concepts by relating them to familiar ideas. People are more open to new ideas when they understand how they relate to things they already know about. In an informative speech about successful Internet fashion businesses, you might discuss the concept of the “virtual model image.” Instead of trying on clothes in a store (a familiar idea), shoppers can see how certain garments would look on their particular body types. By supplying your measurements online, you can visualize what you would look like in outfits by using the virtual model image (new idea).

Define Your Terms. Defining your terms is not just for definitional speeches. In any speech, you should choose terms that your audience will know and understand—and provide clear definitions for any words they might not. If at any point in your speech, audience members find themselves wondering what or who you are talking about, you will begin to lose their attention. When a term comes up that requires definition, you must explain it clearly and succinctly before moving on. If you think an audience is familiar with a word but you just want to be sure, you can simply allude to a more common synonym: “People tend to think of rhinoplasties—commonly referred to as ‘nose jobs’—as cosmetic in nature, but in fact many are performed to help improve nasal functioning.”

Note that definitions are often necessary for proper nouns as well. Audiences may not have a strong background in geography, politics, or world events, so it can be useful to identify organizations and individuals in the same way that you would define a term: “People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals, or PETA, is the largest animal rights organization in the world” or “Colin Powell, a former U.S. Army general and secretary of state under President George W. Bush, noted that . . .” If you can define and identify terms in a way that is smooth and diplomatic, you will enable audience members who are unfamiliar with them to continue to participate in your presentation, while gaining the confidence of audience members who do know the terms and hear you explain them accurately.

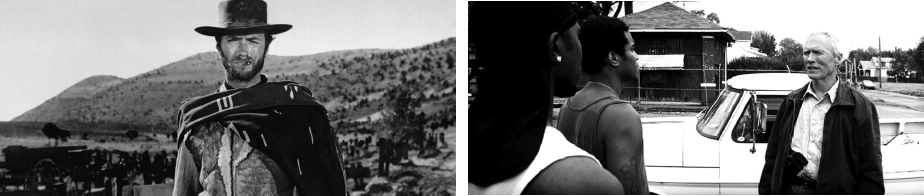

Use Interesting and Appropriate Supporting Material. Select examples that are interesting, exciting, and clear, and use them to reinforce your main ideas. Examples not only support your key points but also provide interesting ways for your audience to visualize what you are talking about. If you are giving a speech about the movie career of Clint Eastwood, you would provide examples of some of his most popular films (Dirty Harry, In the Line of Fire), his early western films (A Fistful of Dollars, Hang ’Em High), his lesser-known films (The First Traveling Saleslady, Honkytonk Man), and his directorial efforts (Gran Torino, Mystic River, J. Edgar). You might also provide quotes from reviews of his films to show the way Eastwood has been perceived at different points in his career.

When you are offering examples to explain a concept, it’s important to choose examples that your audience will understand. Some examples may be familiar enough that you can make quick references to them with little explanation. If you are giving a speech on city planning and rebuilding after disasters, you could probably mention New Orleans after Hurricane Katrina or Haiti after the 2010 earthquake and almost any adult member of your audience will understand your reference. But other examples or audiences might require more detail and explanation. For example, if you are giving a speech about conformity, you might wish to use as an example the incident in Jonestown, Guyana, in 1978, when more than nine hundred members of a religious cult committed mass suicide by drinking cyanide-laced punch. As with many aspects of delivering a speech, audience analysis is crucial: if you are speaking to a younger audience, you’ll need to offer a good deal of explanation to make this example work. However, an audience consisting mainly of baby boomers, historians, or social psychologists would require little more than a brief reference to “Jonestown” to get the point of the example.

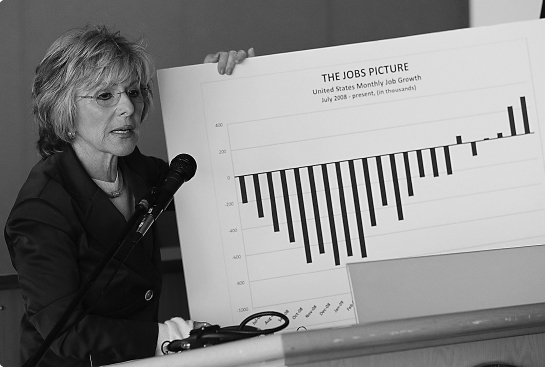

Use Appropriate Presentation Aids. As you will recall from chapter 13, presentation aids can add value to your speech by helping audiences follow and understand the information you present. Such aids can be especially helpful in informative speeches. For example, in an informative speech about the importance of a person’s credit score, the speaker might show (via slides or handouts) sample credit reports. Seeing this information in addition to hearing about it will underscore the importance of your message: everyone has a credit report and a credit score.

Informative speeches also benefit greatly from the use of graphic presentation aids. When describing a process, for example, a flowchart outlining the steps you cover in your speech can help audiences visualize how the process works. Graphs can also be helpful in conveying numerical or statistical information. The combination of hearing your message (the speech content) and seeing your message (through presentation aids) helps the audience retain the content of your informative speech.

Let’s take a look at an informative speech that undergraduate Zachary Dominque gave for his communication course at St. Edward’s University (See p. 327). Zachary chose to inform his audience of fellow students about the history and sport of mountain biking, offering them new and interesting information. Zachary himself is a championship cyclist, and his personal experiences and enthusiasm for the topic help him deliver his message effectively.

Zachary organizes the speech in a topical pattern: each of his main points is a subtopic or category of the overall speech topic of mountain biking. This is one of the most frequently used patterns for informative speeches. Zachary’s speaking outline and references are included here as well.

Technology and You

Some presentation aids can include the entire presentation itself as a downloadable file. In your experience, are downloadable presentations as effective as live ones? Can they replace live presentations, or should they just supplement them?