Schemas: Organizing Perceptions

Schemas: Organizing Perceptions

Page 31

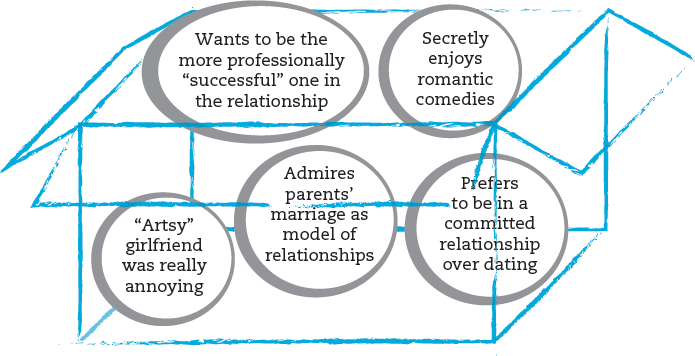

As you receive information, you strive to make sense of it. To do so, you consider the new information but also how it fits with information you already have. For example, in evaluating Irina, speed dater Adam makes associations with his own experience and his own feelings. He compares Irina to his old girlfriend (“artsy”) and to himself, guessing about her professional success. Adam is making sense of the interaction’s many inputs through schemas, mental structures that put together related bits of information (Fiske & Taylor, 1991) (see Figure 2.1). Once put together, these chunks of information form patterns that we use to create meaning.

The Function of Schemas. Your schemas help you understand how things work or should work. Communicators retrieve schemas from memory and interpret new information, people, and situations in accordance with those schemas. For example, imagine that during your walk across campus, a classmate approaches and says, “Hey, what’s up?” An existing schema (memory of past encounters) tells you that you will exchange hellos and then, after some small talk, go your separate ways. When you recognize one component of a schema, the entire schema is activated and tells you what will most probably happen next.

As you go through life, you continually perceive new bits of information that help you make sense of different situations. Your schemas change through this process. Consider the popular Harry Potter books, in which author J. K. Rowling creates a world that continually challenges readers’ (and Harry’s) preconceived schemas. When young Harry first arrives at Hogwarts, he is surprised and delighted by his new environment: candles float, broomsticks fly, chess pieces move by themselves. These events don’t fit Harry’s existing schemas of how things work. Yet during his seven years at Hogwarts, his schemas evolve: things that surprised him in year one no longer raise an eyebrow in year seven.

To send and receive messages that are effective and appropriate, you must be able to process information in a way that makes sense to you but that also is accurately perceived by others.

Challenges with Schemas and Perception. To send and receive messages that are effective and appropriate, you must be able to process information in a way that makes sense to you but that also is accurately perceived by others. Schemas can help you do all of this. However, sometimes schemas can make you a less perceptive communicator; they may cloud your judgment or cause you to rely on stereotypes (discussed later in this chapter) or misinformation. Communication researchers note that schemas present three key challenges to competent communication: mindlessness, selective perception, and undue influence.

Mindlessness. To communicate competently, you must focus on the task at hand, a process called mindfulness. Schemas, however, may make you a less critical processor of information by producing a state of mindlessness, during which you process information passively. Mindlessness helps you handle some transactions automatically; for example, you don’t have to consciously think about how to place an order every time you go to a restaurant. But mindlessness can create problems too—including reduced cognitive activity, inaccurate recall, and uncritical evaluation (Roloff, 1980). Reduced cognitive activity means that when your schemas take effect, you have fewer thoughts; it is like being fatigued. An example of inaccurate recall of information is when your friend asks for directions to a store you’ve shopped at and you can’t remember how, exactly, you got there. Uncritical evaluation means that you don’t question the information you’re receiving, which is problematic if it’s wrong or incomplete.

Selective perception.. Whereas mindlessness is passive, selective perception—that is, biased perception—constitutes active thought. If a group of five people watches a televised debate between two political candidates, they will likely have five different interpretations of what took place and what was important. The person who is keenly interested in economics will likely focus on what the candidates said about the federal budget. The one who’s most concerned about foreign affairs will probably pay closer attention to the candidates’ opinions about that topic.

Ethics and You

Think of an individual whom you hold in high regard, such as a parent, a mentor, or a close friend, and how he or she might influence you. How might you make sure that this person doesn’t hold undue influence over your decisions or opinions?

Undue influence.. When you give greater credibility or importance to something shown or said than should be the case, you are falling victim to undue influence. For example, some people tend to give undue influence to male friends when discussing sports. The media can also be a source of undue influence. For instance, people who have been exposed to local media coverage of crimes are much more likely to perceive defendants in a trial as guilty (Wright & Ross, 1997).