Co-cultural Communication

Co-cultural Communication

Page 61

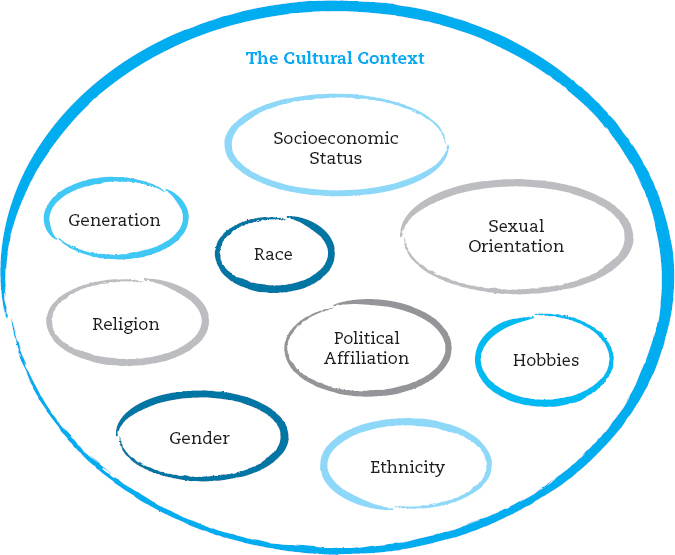

As we discussed in chapter 1, co-cultures are groups whose members share at least some of the general culture’s system of thought and behavior but who also have distinct characteristics or attitudes that unify them and distinguish them from the general culture. As you saw in our example about Ellen and as Figure 3.3 shows, ethnic heritage, race (or races), gender, religion, socioeconomic status, and age form just a few of these co-cultures. But other factors come into play as well: some co-cultures are defined by interest, activities, opinions, or membership in particular organizations (for example, “I am a Republican” or “I am a foodie”).

Our communication is intrinsically tied to our co-cultural experience. For example, a generation is a group of people who were born during a specific time frame and whose attitudes and behavior were shaped by that time frame’s events and social changes. Generations develop different ideas about how relationships work, ideas that affect communication within and between generations (Howe & Strauss, 1992). For example, Americans who lived through the Second World War share common memories (the bombing of Pearl Harbor, military experience, home-front rationing) that have shaped their worldviews in somewhat similar—though not identical—ways. This shared experience affects how they communicate, as shown in Table 3.2

| Table 3.2 Generation as Co-culture | ||

| Generation | Year Born | Characteristics Affecting Communication |

| Matures | Before 1946 | Born before the end of the Second World War, these are the generations that lived through the Great Depression and the war. They are largely conformist, with strong civic instincts. |

| Baby Boomers | 1946–1964 | The largest generation, products of an increase in births that began after the Second World War and ended with the introduction of the birth control pill. In their youths, they were antiestablishment and optimistic about the future, but recent surveys show they are more pessimistic today than any other age group. |

| Generation X | 1965–1980 | Savvy, entrepreneurial, and independent, this generation witnessed the fall of the Berlin Wall and the rise of home computing. |

| Millennials | 1981–2000 | The first generation of the new millennium, this includes people under thirty; the first group to fully integrate computers into their everyday communication. |

Source: Taylor & Keeter, 2010.

Technology and You

Knowing what research states about gender, sex, and communication styles, do you believe the same holds true for online communication? Do you believe you can tell if someone who comments on your favorite blog is male or female based on the words they use? Why or why not? (If possible, test your beliefs.)

Similarly, the interplay between our sex and our gender exerts a powerful influence on our communication. Sex refers to the biological characteristics (that is, reproductive organs) that make us male or female. Gender refers to the behavioral and cultural traits assigned to the sexes; it is determined by the way members of a particular culture define notions of masculinity and femininity (Wood, 2008, 2011).

For example, according to linguistics professor Deborah Tannen, men tend to communicate in a “report” style that is assertive, focused on outcomes, and competitive; men also tend to avoid many other nonverbal behaviors, including touching, gesturing, and using vocalizations (fillers such as “uh-huh”) when communicating with others (Tannen, 1992; Wood, 2009). On the other hand, Tannen noted that many women communicate in a “rapport” style that is collaborative and focused on others’ feelings and needs. This style also tends to include many nonverbal behaviors, such as touching communication partners and giving vocal, facial, and gestural indications that the partner is being heard (Tannen, 1992; Wood, 2009).2

Ethics and You

Have you witnessed others communicating in ways that do not conform to their culture or co-culture (for example, by using masculine or feminine language unexpectedly)? What was the outcome? Did you perceive that communication partner differently? Have you exhibited such behavioral flexibility in your own life? How do you feel you were perceived?

So, are we destined to live our lives bound by the communication norms and expectations for our sex or gender, our generation, our profession, our hobbies, and our other co-cultures? Hardly.

So, are we destined to live our lives bound by the communication norms and expectations for our sex or gender, our generation, our profession, our hobbies, and our other co-cultures? Hardly. Recall the concept of behavioral flexibility discussed in chapter 1. This concept notes that competent communicators adapt their communication skills to a variety of life situations. There are contexts and relationships that call for individuals of both sexes to adhere to a more feminine mode of communication (for example, comforting a distraught family member), while other contexts and relationships require them to communicate in a more masculine way (for example, using direct and confident words when negotiating for a higher salary). Similarly, a teenager who feels most comfortable communicating with others via text messaging or Facebook might do well to send his grandma a handwritten thank-you note for his graduation gift.

Ethics and You

Have you encountered a situation in which someone made assumptions about you or your beliefs based on some aspect of your culture or co-cultures? How did you handle this situation? What was the outcome?

In addition, there is a great diversity of communication behaviors within co-cultures (as well as diversity within larger cultures). For example, your grandmother and your best friend’s grandmother may not communicate in the exact same style simply because they are both women, they were born in the same year, or they were both college graduates who became high-school English teachers.

Similarly, the group typically defined as African Americans includes Americans with a variety of cultural and national heritages. For some, their story stretches back to colonial times; others are more recent immigrants from Africa, the Caribbean, and elsewhere (“Census,” 2010). Christians include a wealth of different denominations that practice various aspects of the larger faith differently. Christians also hail from different races and ethnicities, socio-economic statuses, regions, political views, and so on. All of these intersecting factors affect communication within any given co-culture.