Space and Environment

Space and Environment

Page 108

You also send nonverbal messages by the spaces that surround you and your communication partners. We examine three such factors here: proxemics, territoriality, and environment.

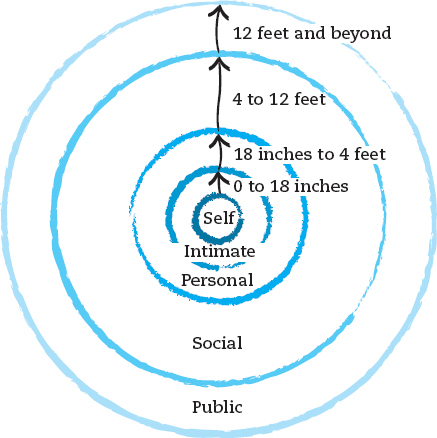

Proxemics. Proxemics is the study of the way we use and communicate with space. Professor Edward Hall (1959) identified four specific spatial zones that carry communication messages (see Figure 5.2).

- Intimate (0 to 18 inches). We often send intimate messages in this zone, which is usually reserved for spouses or romantic partners, very close friends, and close family members.

- Personal (18 inches to 4 feet). In the personal zone, we communicate with friends, relatives, and occasionally colleagues.

- Social (4 to 12 feet). The social zone is most comfortable for communicating in professional settings, such as business meetings or teacher-student conferences.

- Public (12 feet and beyond). The public zone allows for distance between the interactants, such as public speaking events or performances.

THINGS TO TRY

Shake up your clothing and artifacts today. Wear something completely out of character for you, and consider how people react. If you normally dress very casually, try wearing a suit, or if you’re normally quite put together, try going out wearing sweatpants, sneakers, or a T-shirt. If you’re normally a clean-shaven man, try growing a beard for a week, or if you’re a woman who never wears makeup, try wearing lipstick and eyeliner. Do you get treated differently by friends? By strangers (such as store clerks) or professionals (such as doctors or mechanics) with whom you interact?

Your personal space needs may vary from these space categories. They vary according to culture too; Hall “normed” these zones for different cultures around the world. How close or distant you want to be from someone depends on whom you’re dealing with, the situation, and your comfort level. You might enjoy being physically close to your boyfriend or girlfriend while taking a walk together, but you probably don’t hold hands or embrace during class. Gender also plays a role. Research shows that groups of men walking together will walk faster than men walking alone, and typically leave more space between themselves and others (Costa, 2010). But regardless of your personal preferences, violations of space are almost always uncomfortable and awkward and can cause relational problems.

Proxemic messages are not limited to the real world. In the online virtual world Second Life, you create your own space, in which you and your avatar move. Avatars use proxemic cues to send relational messages and structure interaction, much as people do in real life (Antonijevic, 2008; Gillath, McCall, Shaver, & Blascovich, 2008).

Technology and You

How else might you experience proxemics messages in the virtual world? Do you find that there are online equivalents of intimate, personal, social, and public “space”?

Territoriality. Territoriality is the claiming of an area, with or without legal basis, through continuous occupation. Your home, your car, and your office are personal territories. But territories also encompass implied ownership of space, such as a seat in a classroom, a parking space, or a table in a restaurant. Few people like their territory encroached on. If you’re a fan of The Big Bang Theory, then you know never (ever) to take Sheldon Cooper’s seat on the couch, as you will be subjected to a haughty lecture.

Territoriality operates in mediated contexts as well. Just as we do with physical spaces in the real world, we claim our Twitter and Facebook pages by naming them, decorating them with our “stuff,” allowing certain people (“friends”) access, and “cleaning up” by deleting or hiding comments. Research shows that young people are more adept than their parents are at managing space on Facebook (Madden & Smith, 2010). Some clean up their wall regularly, deleting status updates and wall posts as often as they make them. Others use what has become known as a “super logoff”: they deactivate their accounts when they are not online so “friends” cannot see their wall, post anything on it, or tag them in photos while they’re metaphorically not around (Boyd, 2010).

The layout and decoration of your home, your office, and any other space you occupy tell others something about you.

Environment. Any home designer or architect knows that humans use space to express themselves. The layout and decoration of your home, your office, and any other space you occupy tell others something about you. For example, the way you arrange your furniture can encourage interaction or discourage it; the décor, lighting, and cleanliness of the space all send messages about how you want interactions to proceed. The environment’s power to affect communication may explain, in part, the success of shows like Extreme Makeover: Home Edition and Clean House. Episodes often show a dreary or cluttered space transformed into a warm and vibrant room that everyone wants to be in. The best makeovers reflect not only a family’s practical needs but also its unique personalities and interests. That’s because the designers understand that our environment communicates who we are to others.