APPLY AN INTERPRETIVE FRAMEWORK

Need help with context? See Chapter 1 for more information.

An interpretive framework is a set of strategies for identifying patterns that has been used successfully and refined over time by writers interested in a given subject area or working in a particular field. Writers can choose from hundreds (perhaps thousands) of specialized frameworks used in disciplines across the arts, sciences, social sciences, humanities, engineering, and business. A historian, for example, might apply a feminist, social, political, or cultural analysis to interpret diaries written by women who worked in defense plants during World War II, while a sociologist might conduct correlational tests to interpret the results of a survey. In a writing course, you’ll most likely use one of the broad interpretive frameworks discussed here: trend analysis, causal analysis, data analysis, text analysis, and rhetorical analysis.

By definition, analysis is subjective. Your interpretation will be shaped by the question you ask, the sources you consult, and your personal experience and perspective. But analysis is also conducted within the context of a written conversation. As you consider your choice of interpretive framework, reflect on the interpretive frameworks you encounter in your sources and those you’ve used in the past. Keep in mind that different interpretive frameworks will lead to different ways of seeing and understanding a subject. The key to success is choosing one that can guide you as you try to answer your question.

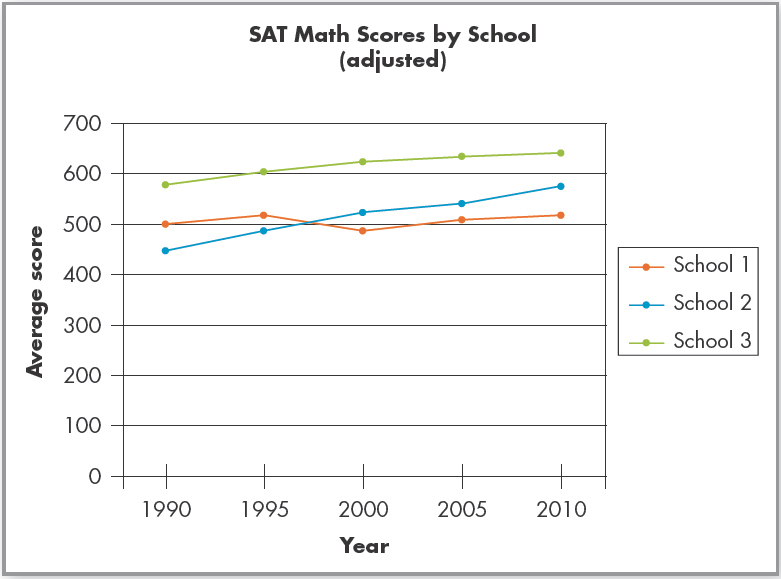

Trend analysis. Trends are patterns that hold up over time. Trend analysis, as a result, focuses on sequences of events and the relationships among them. It is based on the assumption that understanding what has happened in the past allows us to make sense of what is happening in the present and to draw inferences about what is likely to happen in the future.

Trends can be identified and analyzed in nearly every field, from politics to consumer affairs to the arts. For example, many economists have analyzed historical accounts of fuel crises in the 1970s to understand the recent surge in fuel prices. Sports and entertainment analysts also use trend analysis — to forecast the next NBA champion, for instance, or to explain the reemergence of superheroes in popular culture during the last decade.

To conduct a trend analysis, follow these guidelines:

- Gather information. Trend analysis is most useful when it relies on an extensive set of long-term observations. News reports about NASA since the mid-1960s, for example, can tell you whether the coverage of the U.S. space program has changed over time. By examining these changes, you can decide whether a trend exists. You might find, for instance, that the press has become progressively less positive in its treatment of the U.S. space program. However, if you don’t gather enough information to thoroughly establish the trend, your readers might lack confidence in your conclusions.

- Establish that a trend exists. Some analysts seem willing to declare a trend on the flimsiest set of observations: when a team wins an NFL championship for the second year in a row, for instance, fans are quick to announce the start of a dynasty. As you look for trends, cast a wide net. Learn as much as you can about the history of your subject, and carefully assess it to determine how often events related to your subject have moved in one direction or another. By understanding the variations that have occurred over time, you can better judge whether you’ve actually found a trend.

- Draw conclusions. Trend analysis allows you to understand the historical context that shapes a subject and, in some cases, to make predictions about the subject. The conclusions you draw should be grounded strongly in the evidence you’ve collected. They should also reflect your writing situation — your purposes, readers, and context. As you draw your conclusions, exercise caution. Ask whether you have enough information to support your conclusions. Search for evidence that contradicts your conclusions. Most important, on the basis of the information you’ve collected so far, ask whether your conclusions make sense.

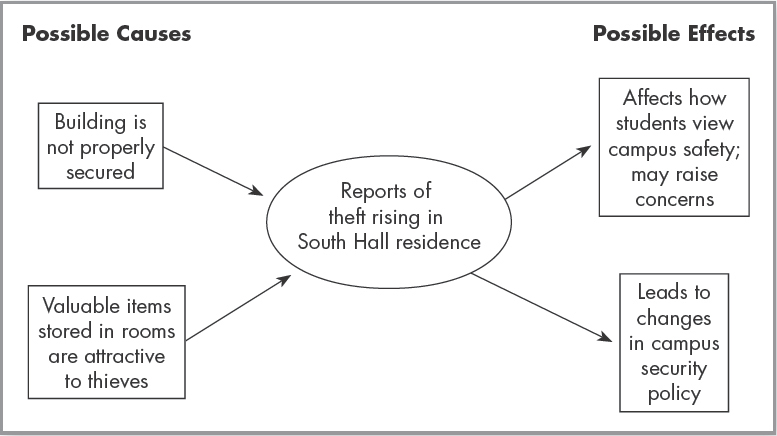

Causal analysis. Causal analysis focuses on the factors that bring about a particular situation. It can be applied to a wide range of subjects, such as the dot-com collapse in the late 1990s, the rise of terrorist groups, or the impact of calorie restriction on longevity. Writers carry out causal analysis when they believe that understanding the underlying reasons for a situation will help people address the situation, increase the likelihood of its happening again, or appreciate its potential consequences.

In many ways, causal analysis is a form of detective work. It involves tracing a sequence of events and exploring the connections among them. Because the connections are almost always more complex than they appear, it pays to be thorough. If you choose to conduct a causal analysis, keep in mind the following guidelines:

- Uncover as many causes as you can. Effects rarely emerge from a single cause. Most effects are the results of a complex web of causes, some of which are related to one another and some of which are not. Although it might be tempting, for example, to say that a murder victim died (the effect) from a gunshot wound (the cause), that would tell only part of the story. You would need to work backward from the murderer’s decision to pull the trigger to the factors that led to that decision, and then further back to the causes underlying those factors.

- Effects can also become causes. While investigating the murder, for instance, you might find that the murderer had long been envious of the victim’s success, that he was jumpy from the steroids he’d been taking in an ill-advised attempt to qualify for the Olympic trials in weight lifting, and that he had just found his girlfriend in the victim’s arms. Exploring how these factors might be related — and determining when they are not — will help you understand the web of causes leading to the effect.

- Determine which causes are significant. Not all causes contribute equally to an effect. Perhaps our murderer was cut off on the freeway on his way to meet his girlfriend. Lingering anger at the other driver might have been enough to push him over the edge, but it probably wouldn’t have caused the shooting by itself.

- Distinguish between correlation and cause. Too often, we assume that because one event occurred just before another, the first event caused the second. We might conclude that finding his girlfriend with another man drove the murderer to shoot in a fit of passion — only to discover that he had begun planning the murder months before, when the victim threatened to reveal his use of steroids to the press just prior to the Olympic trials.

- Look beyond the obvious. A thorough causal analysis considers not only the primary causes and effects but also those that might appear only slightly related to the subject. For example, you might consider the immediate effects of the murder not only on the victim and perpetrator but also on their families and friends, on the wider community, on the lawyers and judges involved in the case, on an overburdened judicial system, even on attitudes toward Olympic athletes. By looking beyond the obvious causes and effects, you can deepen your understanding of the subject and begin to explore a much wider set of implications than you might have initially expected.

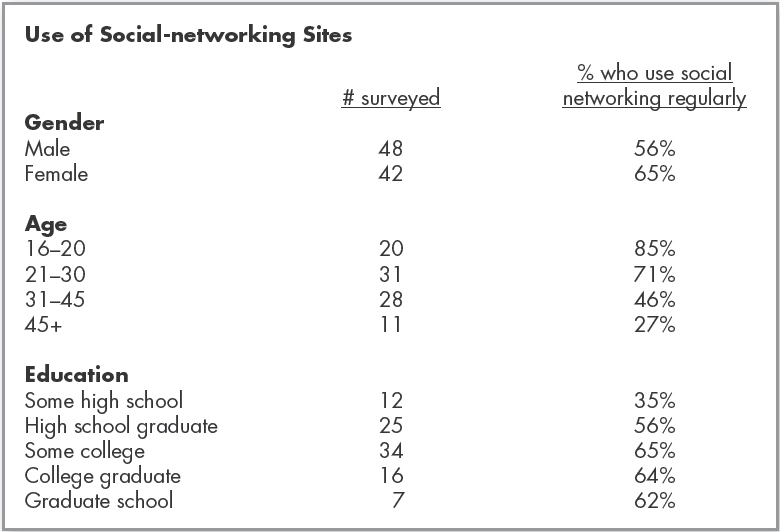

Data analysis. Data is any type of information, such as facts and observations, and is often expressed numerically. Most of us analyze data in an informal way on a daily basis. For example, if you’ve looked at the percentage of people who favor a particular political candidate over another, you’ve engaged in data analysis. Similarly, if you’ve checked your bank account to determine whether you have enough money for a planned purchase, you’ve carried out a form of data analysis. As a writer, you can analyze numerical information related to your subject to better understand the subject as a whole, to look for differences among the subject’s parts, and to explore relationships among the parts.

To begin a data analysis, gather your data and enter the numbers into a spreadsheet or statistics program. You can use the program’s tools to sort the data and conduct tests. If your set of data is small, you can use a piece of paper and a calculator. As you carry out your analysis, keep the following guidelines in mind:

- Do the math. Let’s say you conducted a survey of student and faculty attitudes about a proposed change to the graduation requirements at your school. Tabulating the results might reveal that 52 percent of your respondents were female, 83 percent were between the ages of eighteen and twenty-two, 38 percent were juniors or seniors, and 76 percent were majoring in the biological sciences. You might also find that, of the faculty who responded, 75 percent were tenured. Based on these numbers, you could draw conclusions about whether the responses are representative of your school’s overall population. If they are not, you might decide to ask more people to take your survey. Once you’re certain that you’ve collected enough data, you can draw conclusions about the overall results and determine, for example, the percentage of respondents who favored, opposed, or were undecided about the proposed change.

- Categorize your data. Difference tests can help you make distinctions among groups. To classify the results of your survey, for example, you might compare male and female student responses. Similarly, you might examine differences in the responses between other groups — such as faculty and students; tenured and untenured faculty; and freshmen, sophomores, juniors, and seniors. To carry out your analysis, you might look at each group’s average level of agreement with the proposed changes. Or you might use statistical techniques such as T-Tests, which offer more sensitive assessments of difference than comparisons of averages. You can conduct these kinds of tests using spreadsheet programs, such as Microsoft Excel, or statistical programs, such as SAS and SPSS.

- Explore relationships. Correlation tests allow you to draw conclusions about your subject. For example, you might want to know whether support for proposed changes to graduation requirements increases or decreases according to GPA. A correlation test might indicate that a positive relationship exists — that support goes up as GPA increases. Be cautious, however, as you examine relationships. In particular, be wary of confusing causation with correlation. Tests will show, for example, that as shoe size increases, so do scores on reading tests. Does this mean that large feet improve reading? Not really. The cause of higher reading scores appears to be attending school longer. High school students tend to score better on reading tests than do students in elementary school — and, on average, high school students tend to have much larger feet. As is the case with difference tests, you can use many spreadsheet and statistical programs to explore relationships. If your set of data is small enough, you can also use a piece of paper to examine it.

- Be thorough. Take great care to ensure the integrity of your analysis. You will run into problems if you collect too little data, if the data is not representative, or if the data is collected sloppily. Similarly, you should base your conclusions on a thoughtful and careful examination of the results of your tests. Picking and choosing evidence that supports your conclusion might be tempting, but you’ll do a disservice to yourself and your readers if you fail to consider all the results of your analysis.

Text analysis. Today, the word text can refer to a wide range of printed or digital works — and even some forms of artistic expression that we might not think of as documents. Texts open to interpretation include novels, poems, plays, essays, articles, movies, speeches, blogs, songs, paintings, photographs, sculptures, performances, Web pages, videos, television shows, and computer games.

Students enrolled in writing classes often use the elements of literary analysis to analyze texts. In this form of analysis, interpreters focus on theme, plot, setting, characterization, imagery, style, and structure, as well as the contexts — social, cultural, political, and historical — that shape a work. Writers who use this form of analysis focus both on what is actually presented in the text and on what is implied or conveyed “between the lines.” They rely heavily on close reading of the text to discern meaning, critique an author’s technique, and search for patterns that help them understand the text as fully as possible. They also tend to consider other elements of the wider writing situation in which the text was produced — in particular, the author’s purpose, intended audience, use of sources, and choice of genre.

If you carry out a text analysis, keep the following guidelines in mind:

- Focus on the text itself. In any form of text analysis, the text should take center stage. Although you will typically reflect on the issues raised by your interpretation, maintain a clear focus on the text in front of you, and keep your analysis grounded firmly in what you can locate within it. Background information and related sources, such as scholarly articles and essays, can support and enhance your analysis, but they can’t do the work of interpretation for you.

- Consider the text in its entirety. Particularly in the early stages of learning about a text, it is easy to be distracted by a startling idea or an intriguing concept. Try not to focus on a particular aspect of the text, however, until you’ve fully reviewed all of it. You might well decide to narrow your analysis to a particular aspect of the text, but lay the foundation for a fair, well-informed interpretation by first considering the text as a whole.

- Avoid “cherry-picking.” Cherry-picking refers to the process of using only those materials from a text that support your overall interpretation and ignoring aspects that might weaken or contradict your interpretation. As you carry out your analysis, factor in all the evidence. If the text doesn’t support your interpretation, rethink your conclusions.

Rhetorical analysis. In much the same way that you can assess the writing situation that shapes your work on a particular assignment, you can analyze the rhetorical situation that shaped the creation of and response to a particular document. A rhetorical analysis, for example, might focus on how a particular document (written, visual, or some other form) achieved its purpose or on why readers reacted to it in a specific way.

Rhetorical analysis focuses on one or more aspects of the rhetorical situation.

- Writer and purpose. What did the writer hope to accomplish? Was it accomplished and, if so, how well? If not, why not? What strategies did the writer use to pursue the purpose? Did the writer choose the best genre for the purpose? Why did the writer choose this purpose over others? Are there any clear connections between the purpose and the writer’s background, values, and beliefs?

- Readers/audience. Was the document addressed to the right audience? Did readers react to the document as the writer hoped? Why or why not? What aspects of the needs, interests, backgrounds, values, and beliefs of the audience might have led them to react to the document as they did?

- Sources. What sources were used? Which information, ideas, and arguments from the sources were used in the document? How effectively were they used? How credible were the sources? Were enough sources used? Were the sources appropriate?

- Context. How did the context in which the document was composed shape its effectiveness? How did the context in which it was read shape the reaction of the audience? What physical, social, cultural, disciplinary, and historical contexts shaped the document’s development? What contexts shaped how readers reacted to it?

Rhetorical analysis can also involve an assessment of the argument used in a document. You might examine the structure of an argument, focusing on the writer’s use of appeals — such as appeals to logic, emotion, character, and so on — and the quality of the evidence that was provided. Or you might ask whether the argument contains any logical fallacies. In general, when argument is a key part of a rhetorical analysis, the writer will typically connect the analysis to one or more of the major elements of the rhetorical situation. For example, the writer might explore readers’ reactions to the evidence used to support an argument. Or, as Brooke Gladstone does in her analysis of the Goldilocks number, you might focus on how evidence migrates from one document to another.

Carrying out a rhetorical analysis almost always involves a close reading (or viewing) of the document. It can also involve research into the origins of the document and its effects on its audience. For example, a rhetorical analysis of the Declaration of Independence might focus not only on its content but also on the political, economic, and historical contexts that brought it into existence; reactions to it by American colonists and English citizens; and its eventual impact on the development of the U.S. Constitution.

As you carry out a rhetorical analysis, consider the following guidelines:

- Remember that the elements of a rhetorical situation are interrelated. Writers’ purposes do not emerge from a vacuum. They are shaped by their experiences, values, and beliefs — each of which is influenced by the physical, social, cultural, disciplinary, and historical contexts out of which a particular document emerges. In turn, writers usually shape their arguments to reflect their understanding of their readers’ needs, interests, knowledge, values, beliefs, and backgrounds. Writers also choose their sources and select genres that reflect their purpose, their knowledge of their readers, and the context in which a document will be written and read.

- If you analyze the argument in a document, focus on its structure and quality. Rhetorical analysis focuses on the document as a means of communication. It might be tempting to praise an argument you agree with or to criticize one that offends your values or beliefs. If you do so, however, you won’t be carrying out a rhetorical analysis. This form of analysis is intended to help your readers understand your conclusions about the origins, structure, quality, and potential impact of the document.

- Don’t underestimate the complexity of analyzing rhetorical context. Understanding context is one of the most challenging aspects of a rhetorical analysis. Context is multifaceted. You can consider the physical context in which a document is written and read. You can examine its social context. And you can explore the cultural, disciplinary, and historical contexts that shaped a document. Each of these contexts will affect a document in important ways. Taken together, the interactions among these various aspects of context can be difficult to trace. In fact, a full analysis of context is likely to take far more space and time than most academic documents allow. As you carry out your analysis, focus on the aspects of context that you determine are most relevant to your own writing situation.