Cartels

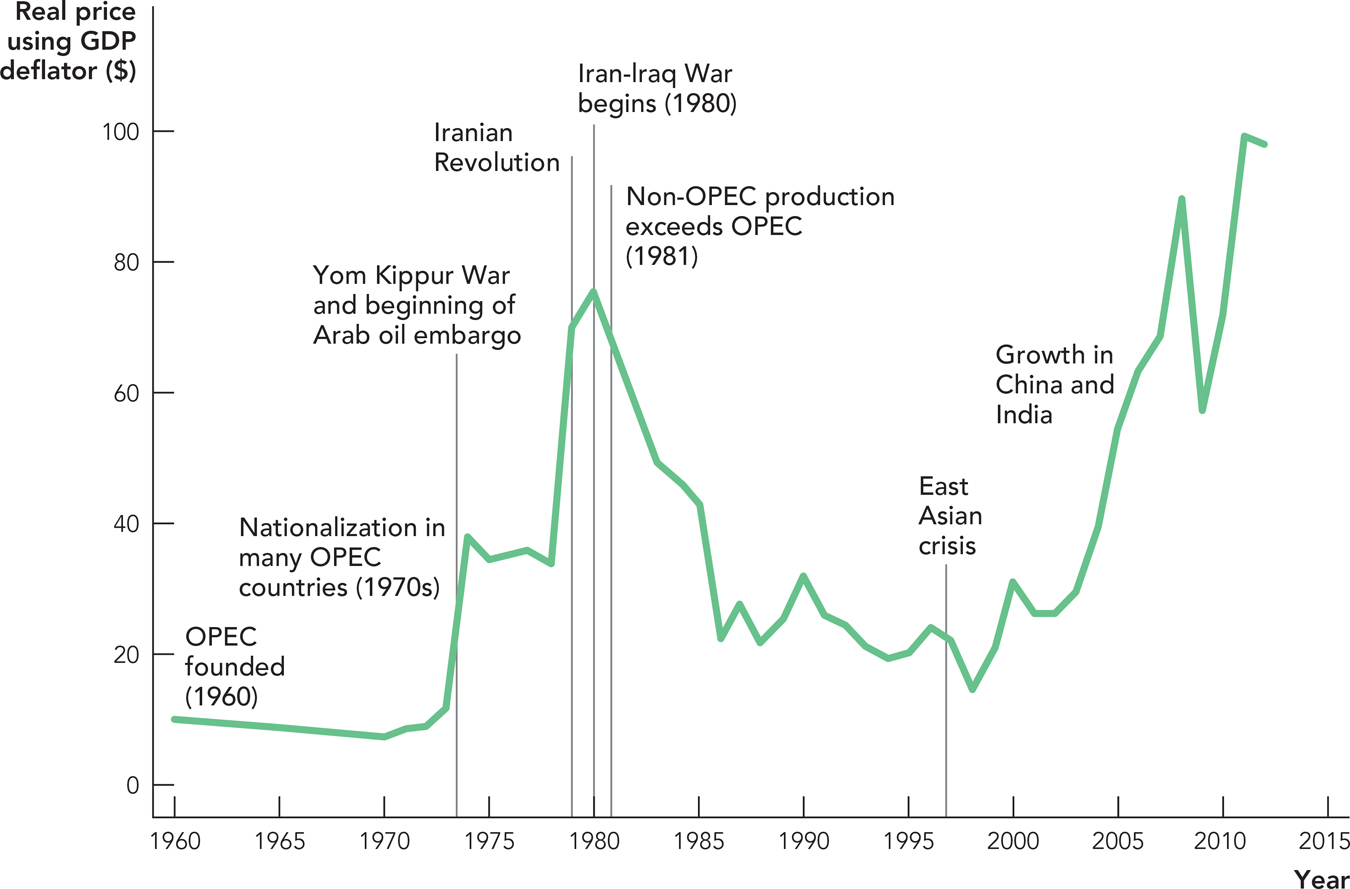

Figure 15.1 shows the price for a barrel of oil from 1960 to 2012. We will focus in this chapter on the dramatic increase in the price of oil in the early 1970s and on the almost equally dramatic fall in the early 1980s. Between 1970 and 1974, the price of oil shot up from $7 per barrel to almost $38 a barrel. What happened? The answer is simple: Led by Saudi Arabia, a cartel of oil-exporting countries cut back on their production of oil.*

Source: BP Statistical Review of World Energy, 2013

Note: Corrected for inflation using the GDP Deflator ($2005)

283

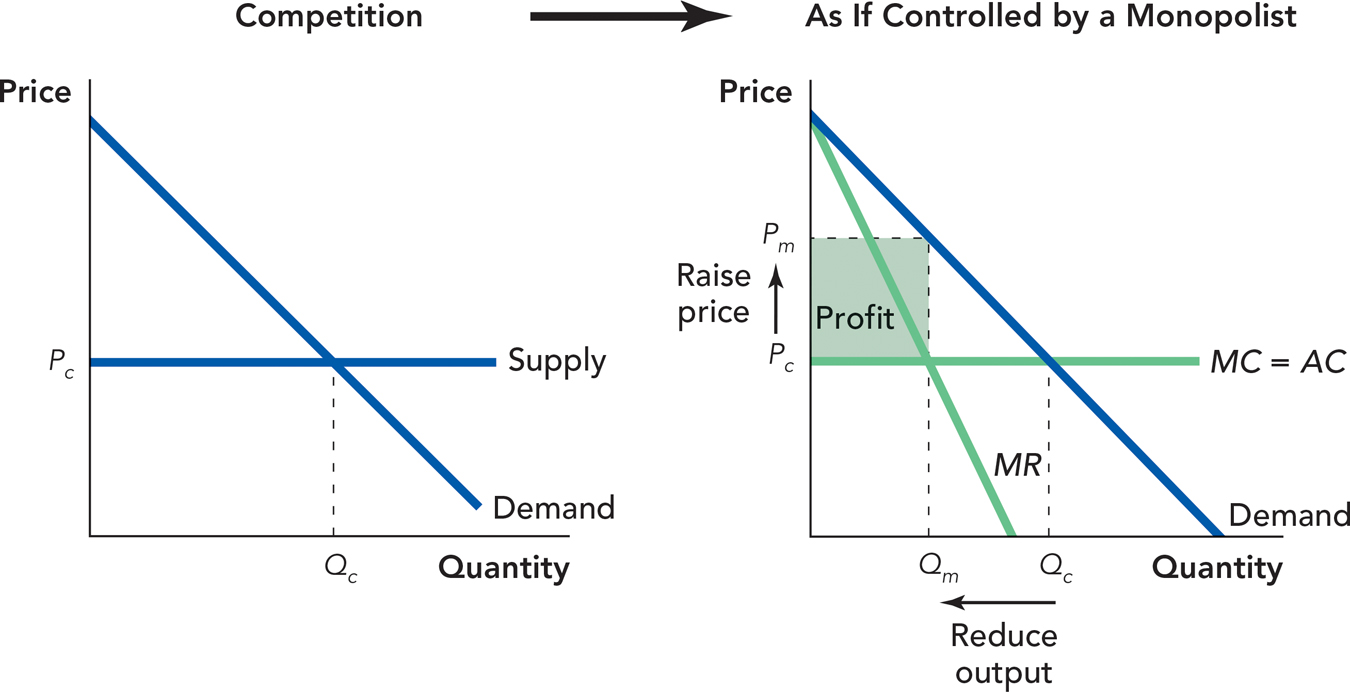

The left panel of Figure 15.2 shows a competitive market in a constant-cost industry so the supply curve is flat (the constant-cost assumption makes the analysis simpler but is not necessary); remember that in a competitive market each supplier earns zero economic profit. The right panel shows the same market but now run as if it were controlled by a monopolist; profits, shown in green, are maximized. A cartel is not a monopolist, but if all the firms in a market could be convinced to cut supply so that total supply fell from Qc to Qm, then each firm could share in the “monopoly” profits. Thus, a cartel is an organization of suppliers who try to move the market from the left panel of Figure 15.2 to the right panel, that is, from “Competition” toward “As if Controlled by a Monopolist.”

Very few cartels can move an industry from competition to pure monopoly, but Figure 15.2 shows the basic tendency of cartels to reduce output and raise price.

It might seem from this short look at OPEC that cartels are all-powerful. But in reality few cartels—unless they have strong government support—have much control over market price for very long. A cartel is a deal in which businesspeople promise: “I will raise my price and cut back my production if you promise to do the same.” But will the promise be kept?

Cartels tend to collapse and lose their power for three reasons:

Cheating by the cartel members

New entrants and demand response

Government prosecution and regulation

OPEC, although a relatively successful cartel by historical standards, could not keep the price of oil high for very long. By 1986, the price of oil had plummeted from its previous heights of $75 per barrel to around $20 per barrel and sometimes falling as low as $10 per barrel. OPEC nations were unhappy, but there was little they could do to keep oil prices high.

How did this happen? To understand, let’s turn to the first reason why cartels collapse, namely cheating by the cartel members.

284

The Incentive to Cheat

If a cartel succeeds, cartel members earn high profits on each barrel of oil that comes out of the ground but this same desire for profit makes the cartel fall apart. Members will cheat on the cartel agreement. That is, they will promise to reduce production, but when everyone else reduces production and the price of oil rises, some cartel members will cheat by producing more than they promised. If everyone else is keeping their promises, the cheaters will increase their profits. At first, only a few firms might cheat, but the more cheaters, the less profitable it is to reduce production and cheating will soon increase.

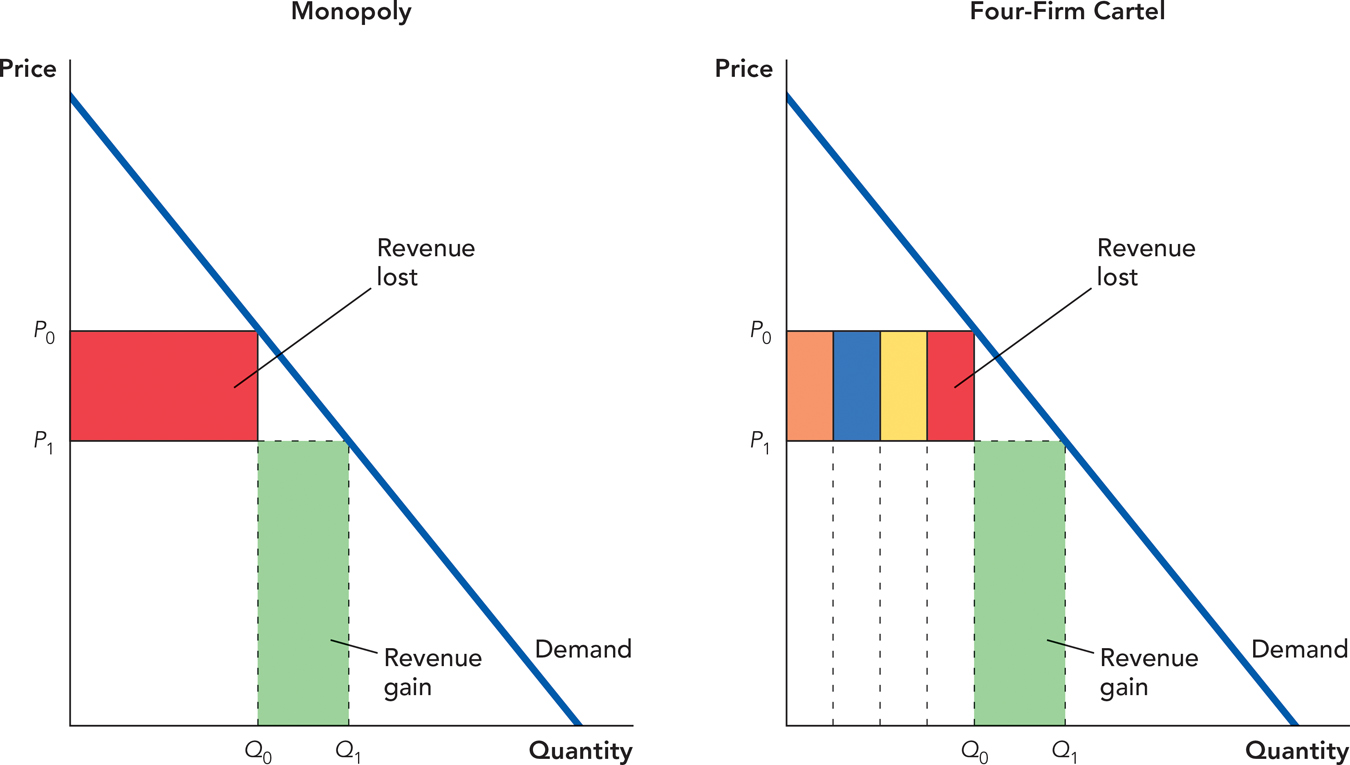

We can get another perspective on the incentive to cheat by comparing a monopolist with a cartel member. When a monopolist increases quantity beyond the profit-maximizing quantity, the monopolist hurts itself. But when a cartel cheater increases quantity beyond the profit-maximizing quantity, the cheater benefits itself and hurts other cartel members. In Figure 15.3, we compare the incentive to lower price for a monopolist and for a member of a four-firm cartel.

When a single firm in a four-firm cartel increases quantity from Q0 to Q1 it gets all of the revenues from the new sales (the green area), but the fall in price is spread across all firms in the industry in proportion to their sales so the cartel member loses only the much smaller red area. The cartel member, therefore, has a much larger incentive to increase output than does the monopolist.

When a monopolist lowers the price and increases its sales, it enjoys all of the gains from selling more (the green area in the left panel of Figure 15.3), but it also bears all of the losses from selling its previous output at a lower price (the red area). But if a four-firm cartel member cheats on the cartel, it enjoys all of the gains from selling more (the green area), but it bears only a quarter of the losses from a lower price (the red area in the right panel).

285

If a cheater hurts the other cartel members, not so many tears will be shed by the cheater. This is especially true for the OPEC cartel. Iran and Iraq, for example, fought a major war from 1980 to 1988, with more than 800,000 people killed. The war saw the use of poison gas, chemical weapons, and child soldiers as advance scouts to trigger land mines. While this war was going on, Iran and Iraq were both in OPEC. Each nation, in effect, was promising it would not undercut the other when it came to selling more oil at a lower price. Do you really think they felt obliged to keep their word?

And so have most cartels ended. The more successful the cartel is in raising member profits, the greater the incentive to cheat. And once a cartel falls apart, it is difficult to put it back together again. Everyone correctly expects cheating to be the norm.

No One Wins the Cheating Game

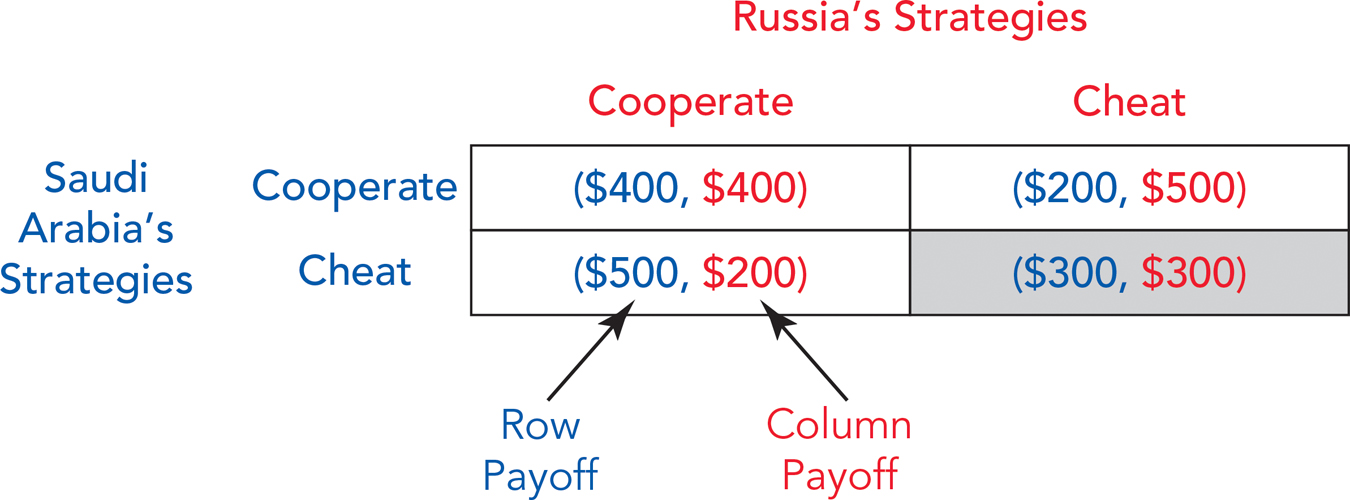

It’s useful to show the incentive to cheat in another way, using what is called a payoff table. With more than two firms, the payoff table would be quite complicated and hard to draw in two dimensions, but the same logic of cheating applies if there are just two firms. So imagine that the oil market is dominated by two large firms, Saudi Arabia and Russia.

Saudi Arabia has two choices or strategies, Cooperate (by cutting back production) or Cheat. These strategies are shown in Figure 15.4 by the rows of the payoff table. Russia also has the same two strategies, shown as the columns of the payoff table.

The two numbers in each box of the table are the payoffs to the players; the first number is the payoff to Saudi Arabia, the second to Russia. For instance, if both Saudi Arabia and Russia choose to cooperate by cutting back production, the payoff is $400 (million per day) to Saudi Arabia and $400 (million per day) to Russia. If Saudi Arabia cheats and Russia cooperates, then the payoff to Saudi Arabia is $500 and the payoff to Russia is $200.

286

Now let’s see what the “players” will do in this “game.” Consider the incentives faced by Saudi Arabia. If Russia cooperates, then Saudi Arabia can choose Cooperate and receive a payoff of $400 or choose Cheat and receive a payoff of $500. Since $500 is more than $400, Saudi Arabia’s best strategy if Russia cooperates is to cheat.

A dominant strategy is a strategy that has a higher payoff than any other strategy no matter what the other player does.

What is Saudi Arabia’s best strategy if Russia cheats? If Russia cheats, Saudi Arabia can cooperate and earn a payoff of $200 or Saudi Arabia can cheat and earn a payoff of $300. Cheat is again the more profitable strategy. A strategy that has a higher payoff than any other strategy, no matter what the other player does, is called a dominant strategy. In this setup, cheating is a dominant strategy for Saudi Arabia.

Cheating is also a dominant strategy for Russia. If Saudi Arabia cooperates, Russia earns $500 by choosing Cheat and $400 by choosing Cooperate. If Saudi Arabia cheats, Russia earns $300 by choosing Cheat and $200 by choosing Cooperate. Thus, both Saudi Arabia and Russia will cheat and we shade (Cheat, Cheat) to show that this is the equilibrium outcome of the game.

The logic is compelling but also surprising. When Saudi Arabia and Russia each follow their individually sensible strategy of Cheat, each receives a payoff of $300. If Saudi Arabia and Russia instead both chose to cooperate, a strategy that is not individually sensible, they will receive a higher payoff of $400. Thus, when Saudi Arabia acts in its interest and Russia acts in its interest, the result is an outcome that is in the interest of neither. That is a dilemma well verified by both theory and evidence.