Oligopolies

Cartels are difficult to form and maintain, but an oligopoly that fails to form a cartel is still very likely to maintain prices above competitive levels. In Figure 15.3, we showed how a cartel member has an incentive to cheat on the agreement by lowering price and producing more than the assigned quota. Exactly the same diagram shows why the price in an oligopoly is likely to be below the monopoly price. A firm in an oligopoly that produces more and cuts price earns all the gains for itself, but bears only a fraction of the costs. Thus, prices in an oligopoly are likely to be below monopoly levels, but how will prices in an oligopoly compare with competitive levels?

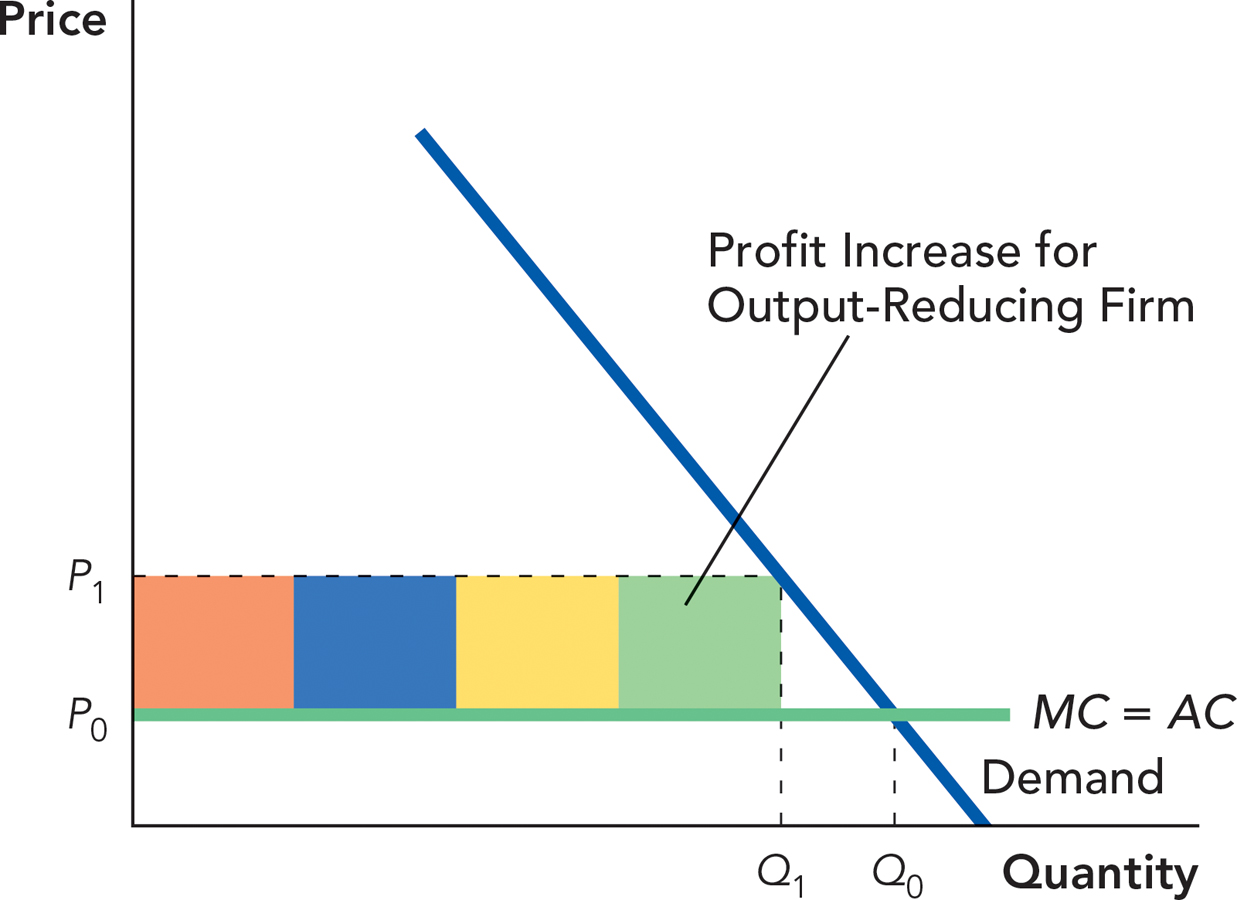

In Figure 15.6, we show how an oligopolist has an incentive to raise prices above competitive levels. Imagine first that the oligopolistic market is producing at competitive levels. Recall from Chapter 11 that this means the price is equal to marginal cost and no firm is making an above-normal profit. In Figure 15.6, the competitive price and quantity are P0 (=MC) and Q0. Now suppose that one firm in, say, a four-firm oligopoly were to cut output by Q0 − Q1, thus raising the price to P1. At P1, every firm in the industry is making a profit since P1 > MC. In particular, even the firm that cut its output increased its profits since before it was making zero profits and now it is making positive profits, as shown by the green area.

But a firm in a four-firm oligopoly who reduces quantity by the amount Q0 − Q1 increases the market price to P1 which is greater than MC. The increase in price increases the profits of the firm that cuts output (the green area), as well as increasing the profits of the other firms in the industry.

In a competitive industry, no firm is able to influence the price, so a competitive firm has no incentive to reduce output. In an oligopoly, each firm is large relative to the total size of the market. Thus, a firm in an oligopoly has some influence over the price and therefore has an incentive to reduce output and increase price from the competitive level.

CHECK YOURSELF

The auto industry is an oligopoly: It has a small number of very large firms. Why don’t we call the auto industry a cartel?

The auto industry is an oligopoly: It has a small number of very large firms. Why don’t we call the auto industry a cartel?

When a firm in an oligopoly reduces output, who gets most of the gains from the reduction: the firm that reduces output or the other firms in the industry?

When a firm in an oligopoly reduces output, who gets most of the gains from the reduction: the firm that reduces output or the other firms in the industry?

Figure 15.3 and Figure 15.6 tell us that price in an oligopoly is likely to be below monopoly levels but above competitive levels. Moreover, we can also see that the more firms in the oligopoly, the greater the incentive to cut price from monopoly levels and the smaller the incentive to increase price above competitive levels. Thus, we can also predict that the more firms in an industry, the closer price will be to competitive levels.

Can we be more precise about pricing in an oligopolistic market? Economists have developed many models of oligopolistic pricing. Famous models in this literature include those by Bertrand, Cournot and Nash, and Stackelberg. Each of these models has its uses, but it’s difficult to say that one model is best for all purposes. A lot depends on factors specific to the industry; the right model for the auto industry might not be the right model for the soft-drink industry or the aircraft industry. The field of industrial organization has a lot more to say about the specifics of oligopoly.

290