Business Strategy and Changing the Game

The prisoner’s dilemma game suggests that collusion is difficult (although as we also saw there are more possibilities for collusion/cooperation with repeated interactions). Every firm wants market power, however, so what can firms do? One possibility is to change the game! Let’s take a look at two strategies that on the surface seem competitive and proconsumer but that may also have hidden and less beneficial consequences: price match guarantees and loyalty programs such as frequent flyer points.

The Danger of Price Matching Guarantees

What’s not to like when a firm guarantees that it will match the price of any competitor and even pay the consumer 10% of the difference? Isn’t this a great example of competition at its finest? Not so fast. To evaluate the effects of these policies, we need some game theory.

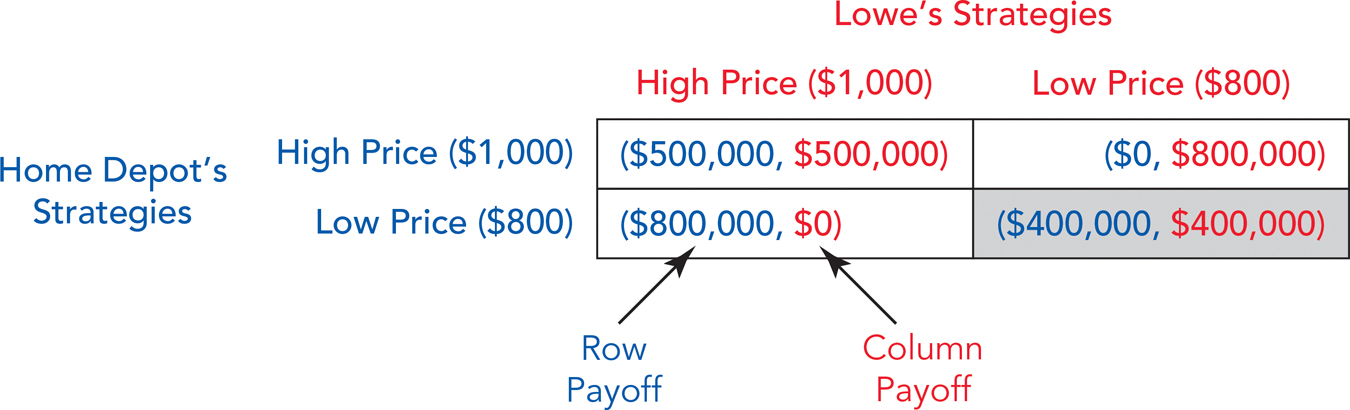

Suppose that Lowe’s and Home Depot are locked into a price war over refrigerator sales. Each firm could set a high price of $1,000 or a low price of $800. Let’s also assume that costs are zero (this is convenient but doesn’t affect the results) and that there are 1,000 consumers. If both firms set a high price, each gets 500 consumers and makes a profit of $500,000 ($1,000 × 500). If one firm sets a low price ($800) while the other firm continues to set a high price, then the low-price firm gets all the customers (1,000) and makes more money, $800,000. If both firms set a low price, then they again split the market and each makes $400,000. The payoffs are shown in Figure 15.7.

Notice that this is just another version of the prisoner’s dilemma. No matter what strategy Lowe’s chooses, it’s best for Home Depot to choose Low Price, and no matter what strategy Home Depot chooses, it’s best for Lowe’s to choose Low Price. Thus each firm chooses its dominant strategy and the equilibrium outcome is Low Price, Low Price.

293

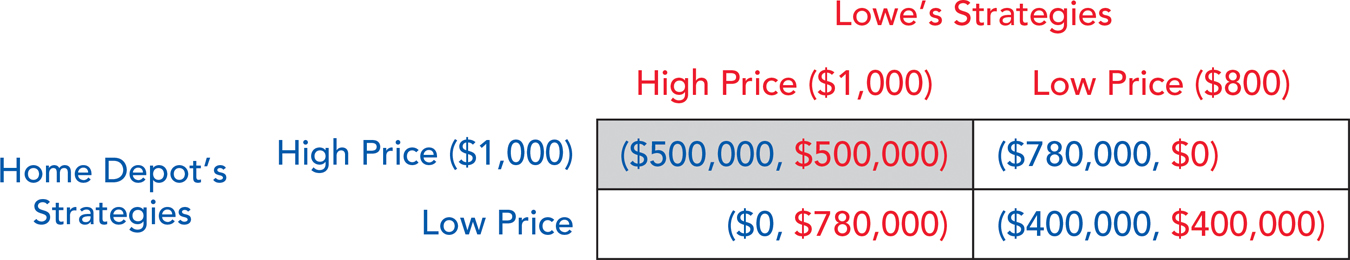

But now let’s imagine that each firm offers to match any competitor’s price plus give the consumer 10% of the difference. Assume, for example, that Home Depot posts a price of $800. Which firm gets the sales? If Home Depot posts a price of $800 but Lowe’s guarantees to match the price and give the consumer 10% of the difference, then a consumer can, in effect, buy the refrigerator from Lowe’s for $780 ($800 minus 10% of the $200 difference in posted price). By lowering its price, Home Depot ensures that Lowe’s sells all the refrigerators and makes $780,000 in profit. Notice that it’s Lowe’s, the firm with the high posted price, that makes the profits! Similarly, if Lowe’s posts a Low Price while Home Depot posts a High Price, Home Depot gets all the sales and the profits! Cutting prices no longer looks like a good idea. As before, if both firms choose High Price, they split the market and make $500,000 each, and if both choose Low Price, they make $400,000 each. The new payoffs are shown in Figure 15.8.

294

The price match guarantee changes the payoffs and that changes the game. In the new game, the dominant strategy is to choose High Price. Once again, let’s look at Lowe’s incentives. If Home Depot chooses High Price, then Lowe’s earns $500,000 by choosing High Price and only $0 by choosing Low Price. If Home Depot chooses Low Price, then Lowe’s earns $780,000 by choosing High Price and only $400,000 by choosing Low Price. Thus, whatever choice Home Depot makes, it’s better for Lowe’s to choose High Price! Once again what makes this work is that when Lowe’s chooses to post a Low Price, consumers run to buy from Home Depot, which despite a high posted price offers to match the Lowe’s price and give consumers 10% of the difference in prices. The game is symmetric so for the same reasons that Lowe’s has an incentive to choose High Price, Home Depot also has an incentive to choose High Price.

Amazingly, a price match guarantee that looks proconsumer changes the equilibrium strategies from {Low Price, Low Price} to {High Price, High Price}. A price match guarantee and a promise to pay 10% of the difference in price turns out to be a clever strategy that reduces the incentive of firms to compete with lower prices!

The High Price of Loyalty

In addition to price guarantees, businesses can also reduce their incentives to lower prices by using loyalty plans. A customer loyalty plan gives regular customers special treatment or a better price. The best known customer loyalty plans are probably frequent flyer miles on airlines, but you will find customer loyalty plans at Barnes & Noble, at Starbucks, and at your local Giant and Safeway supermarkets.

Let’s take a look at frequent flyer plans. If you join a frequent flyer plan, you get points every time you fly, points that can be used to get a free ticket to Hawaii or Paris once you have accumulated enough. Alex and Tyler are both members of the United frequent flyer plan because United has the most flights out of Washington, D.C., our usual takeoff point. Now when we book travel we are slightly more likely to book a United flight so that we can accumulate points toward a free trip. So what’s not to like?

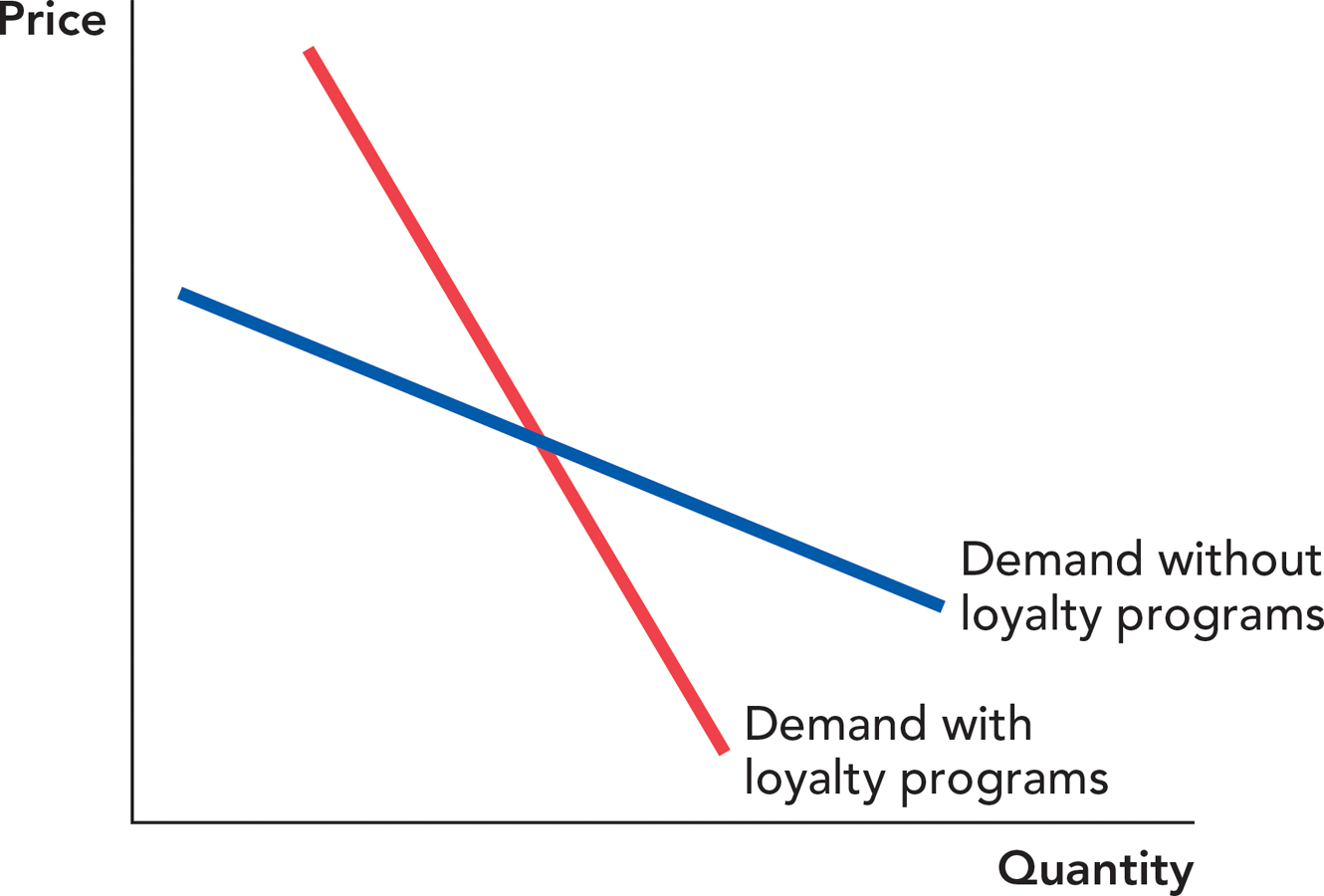

The trick is this: Suppose United, U.S. Airways, Delta, and the other major airlines all offer frequent flyer plans. Loyal customers of each of these companies feel good that they are getting points toward a free trip, but once customers are loyal—that is, once they are a bit locked in—the different airlines don’t have to compete with each other quite as much. United realizes that if it raises its prices a little, its customers will remain loyal, and if it lowers its prices a little, the customers of the other airlines will also remain loyal! Thus, United has more incentive to raise its prices and less incentive to lower its prices. Loyalty increases monopoly power, and each airline, facing a more inelastic demand curve, will raise prices. See Figure 15.9. As a result, the net effect of more points is higher prices! A cynic might say that exploitation is the price of loyalty.

295

When you get your free flight to Hawaii, you feel like a winner, but the reality is that you are being conned just a little. It does you no good, however, to stay out of the plans and refuse to use the points. If you refuse to join the loyalty plan, you lose the points. Furthermore, your refusal won’t increase competition in the airline market enough to get airlines to lower their prices across the board. Customers are better off refusing to join the loyalty plan only if all or most of them refuse, in which case each airline will face a more elastic demand curve and prices will fall for everyone. Loyalty plans put customers in a type of prisoner’s dilemma—it’s good for a single customer to join the loyalty plan, but if all the customers join, the result is bad for them as a whole. As you know from the analysis of the prisoner’s dilemma, it’s going to be difficult to organize a mass boycott of loyalty plans.

By the way, limiting competitive pressure is not the only motivation for customer loyalty plans like frequent flyer programs. Frequent flyer programs also are a form of price discrimination (Chapter 14), as perhaps only the more budget-conscious travelers take the trouble to sign up for miles and cash them in, sometimes altering their flight plans to save the money. Over time, the budget-conscious travelers, who redeem their miles conscientiously and thus get some free flights, pay lower average prices for flying than do the non-budget-conscious travelers. Frequent flyer programs also encourage business travelers to sometimes take the more expensive flight; the traveler will get miles on the preferred airline but the employer will pay the higher price; the airline is indirectly “bribing” the employee to take advantage of the employer. Finally, firms may deliberately let employees keep their frequent flyer miles, even if it means paying for higher ticket prices come reimbursement time. It’s one way of rewarding employees while skirting taxes (legally) because the use of frequent flyer miles is not considered taxable income or a reward. If you really value the extra flights, you can save up to 40% in value by avoiding the taxation of ordinary monetary income and by taking your marginal compensation in the form of miles. Frequent flyer miles are a good example of how, if you look closely, you will see economics everywhere.

Other Ways of Changing the Game

Firms want market power and sometimes that can be at the expense of consumers, but keep in mind that the pursuit of market power can often lead to the social good! One reason that firms innovate, for example, is that by doing so they can produce a good with fewer substitutes. Fewer substitutes means a more inelastic demand curve and that means that firm can charge a higher price and earn a higher profit (all else being equal). Similarly, firms also try to reduce the number of substitutes for their product by differentiating their product with different styles or varieties. Apple, Samsung, and Microsoft all produce cell phones but by differentiating the features, looks, and capabilities, they compete with one another less than if the phones were more similar.

Innovation and product differentiation, however, are usually good things so the pursuit of market power is part of what makes for a competitive, dynamic economy. Less competition is good for firms but at the same time we want firms to have an incentive to innovate. The market is not just a process for reducing price to marginal cost—it’s also a discovery process, a way of figuring out what products and features consumers really want. We will discuss product differentiation and competing for market (monopoly) power at greater length in Chapter 16 and Chapter 17.

296