CHAPTER REVIEW

FACTS AND TOOLS

Question 13.11

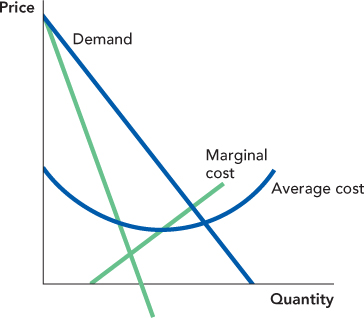

1. In the following diagram, label the marginal revenue curve, the profit-maximizing price, the profit-maximizing quantity, the profit, and the deadweight loss.

Question 13.12

2.

Consider a market like the one illustrated in Figure 13.5, where all firms have the same average cost curve. If a competitive firm in this market tried to set a price above the minimum point on its average cost curve, how many units would it sell?

If a monopoly did the same thing, raising its price above average cost, what would happen to the number of units it sells: Does it rise, fall, or remain unchanged?

What accounts for the difference between your answers to parts a and b?

Question 13.13

3.

In the textbook The Applied Theory of Price, D. N. McCloskey refers to the equation MR = MC as the rule of rational life. Who follows this rule: monopolies, competitive firms, or both?

Rapido, the shoe company, is so popular that it has monopoly power. It’s selling 20 million shoes per year, and it’s highly profitable. The marginal cost of making extra shoes is quite low, and it doesn’t change much if the company produces more shoes. Rapido’s marketing experts tell the CEO of Rapido that if it decreased prices by 20%, it would sell so many more shoes that profits would rise. If the expert is correct, at its current output, is MC > MR, is MC = MR, or is MR > MC?

If Rapido’s CEO follows the expert’s advice, what will this do to marginal revenue: Will it rise, fall, or be unchanged? Will Rapido’s total revenue rise, fall, or be unchanged?

Apollo, another highly profitable shoe company, also has market power. It’s selling 15 million shoes per year, and it faces marginal costs quite similar to Rapido’s. Apollo’s marketing experts conclude that if the company increased prices by 20%, profits would rise. For Apollo, is MC > MR, is MC = MR, or is MR > MC?

Question 13.14

4.

When selling e-books, music on iTunes, and downloadable software, the marginal cost of producing and selling one more unit of output is essentially zero: MC = 0. Let’s think about a monopoly in this kind of market. If the monopolist is doing its best to maximize profits, what will marginal revenue equal at a firm like this?

All firms are trying to maximize their profits (TR – TC). The rule from part a tells us that in the special case where marginal cost is zero, “profit maximization” is equivalent to which of the following statements?

“Maximize total revenue”

“Minimize total cost”

“Minimize average cost”

“Maximize average revenue”

Question 13.15

5.

What’s the rule: Monopolists charge a higher markup when demand is highly elastic or when it’s highly inelastic?

What’s the rule: Monopolists charge a higher markup when customers have many good substitutes or when they have few good substitutes?

For the following pairs of goods, which producer is more likely to charge a bigger markup? Why?

Someone selling new trendy shoes, or someone selling ordinary tennis shoes?

A movie theater selling popcorn or a New York City street vendor selling popcorn?

A pharmaceutical company selling a new powerful antibiotic or a firm selling a new powerful cure for dandruff?

Question 13.16

6. In 1996, the X Prize Foundation created what became known as the Ansari X Prize—a $10 million prize for the first nongovernment group to send a reusable manned spacecraft into space twice within two weeks. In 2004, it was won by the Tier One project, financed by Microsoft cofounder Paul Allen.

An answer you can find on the Internet: How high did SpaceShipOne fly when it won the Ansari X Prize?

How much did it cost to develop SpaceShipOne? Was the $10 million prize enough to cover the costs? Why do you think Microsoft cofounder Paul Allen invested so much money to win the prize? Do Allen’s motivations show up in our monopoly model?

Question 13.17

7. Which of the following is true when a monopoly is producing the profit-maximizing quantity of output? More than one may be true.

Marginal revenue = Average cost

Total cost = Total revenue

Price = Marginal cost

Marginal revenue = Marginal cost

Question 13.18

8.

Consider a typical monopoly firm like that in Figure 13.3. If a monopolist finds a way to cut marginal costs, what will happen: Will it pass along some of the savings to the consumer in the form of lower prices, will it paradoxically raise prices to take advantage of these fatter profit margins, or will it keep the price steady?

Is this what happens when marginal costs fall in a competitive industry, or do competitive markets and monopolies respond differently to a fall in costs?

Question 13.19

9.

Where will profits be higher: when demand for a patented drug is highly inelastic or when demand for a patented drug is highly elastic? (Figure 13.4 may be helpful.)

Which of those two drugs is more likely to be “important?” Why?

Now, consider the lure of profits: If a pharmaceutical company is trying to decide what kind of drugs to research, will it be lured toward inventing drugs with few good substitutes or drugs with many good substitutes?

Is your answer to part c similar to what an all-wise, benevolent government agency would do, or is it roughly the opposite of what an all-wise, benevolent government agency would do?

Question 13.20

10. True or False?

When a monopoly is maximizing its profits, price is greater than marginal cost.

For a monopoly producing a certain amount of output, price is less than marginal revenue.

When a monopoly is maximizing its profits, marginal revenue equals marginal cost.

Ironically, if a government regulator sets a fixed price for a monopoly lower than the unregulated price, it is typically raising the marginal revenue of selling more output.

In the United States, government regulation of cable TV cut down the price of premium channels to average cost.

When consumers have many options, monopoly markup is lower.

A patent is a government-created monopoly.

THINKING AND PROBLEM SOLVING

Question 13.21

1. In addition to the clove monopoly discussed in this chapter, Tommy Suharto, the son of Indonesian President Suharto (in office from 1967 to 1998), owned a media conglomerate, Bimantara Citra. In their entertaining book, Economic Gangsters (Princeton University Press, 2008), economists Raymond Fisman and Edward Miguel compared the stock price of Bimantara Citra with that of other firms on Indonesia’s stock exchange around July 4, 1996, when the government announced that President Suharto was traveling to Germany for a health checkup. What do you think happened to the price of Bimantara Citra shares relative to other shares on the Indonesian stock exchange? Why? What does this tell us about corruption and monopoly power in Indonesia?

Question 13.22

2.

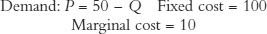

Sometimes, our discussion of marginal cost and marginal revenue unintentionally hides the real issue: the entrepreneur’s quest to maximize total profits. Here is information on a firm:

Using this information, calculate total profit for each of the values in the following table, and then plot total profit in the figure. Clearly label the amount of maximum profit and the quantity that produces this level of profit.

Page 254Quantity

Total Revenue

Total Cost

Total Profit

18

19

20

21

22

23

If the fixed cost increased from 100 to 200, would that change the shape of this curve at all? Also, would it shift the location of the curve to the left or right? Up or down? How does this explain why you can ignore fixed costs most of the time when thinking about a monopoly’s decision-making process?

Question 13.23

3. When a sports team hires an expensive new player or builds a new stadium, you often hear claims that ticket prices have to rise to cover the new, higher cost. Let’s see what monopoly theory says about that. It’s safe to treat these new expenses as fixed costs: something that doesn’t change if the number of customers rises or falls. You have to pay Miguel Cabrera the same salary whether people show up or not; you have to make the interest payments on the new Comerica Park whether the seats are filled or not. Treat the local sports team as a monopoly in this question, and to keep it simple, let’s assume there is only one ticket price.

As long as the sports team is profitable, will a mere rise in fixed costs raise the equilibrium ticket price, lower the equilibrium ticket price, or have no effect whatsoever on the equilibrium ticket price? Why?

In fact, it seems common in real life for ticket prices to rise after a team raises its fixed costs by building a fancy new stadium or hiring a superstar player: In recent years, it’s happened in St. Louis’s and San Diego’s baseball stadiums. What’s probably shifting to make this happen? Name both curves, and state the direction of the shift.

So, do sports teams spend a lot of money on superstars so that they can pass along the costs to the fans? Why do they spend a lot on superstars, according to monopoly theory? (Note: Books like Moneyball and The Baseball Economist apply economic models to the national pastime, and it’s common for sports managers to have solid training in economic methods.)

Question 13.24

4. Earlier we mentioned the special case of a monopoly where MC = 0. Let’s find the firm’s best choice when more goods can be produced at no extra cost. Since so much e-commerce is close to this model—where the fixed cost of inventing the product and satisfying government regulators is the only cost that matters—the MC = 0 case will be more important in the future than it was in the past. In each case, be sure to see whether profits are positive! If the “optimal” level of profit is negative, then the monopoly should never start up in the first place; that’s the only way it can avoid paying the fixed cost.

P = 100 – Q Fixed cost = 1,000

P = 2,000 – Q Fixed cost = 900,000 (Driving the point home from part a.)

P = 120 – 12Q Fixed cost = 1,000

Question 13.25

5.

Just based on self-interest, who is more likely to support strong patents on pharmaceuticals: young people or old people? Why?

Who is more likely to support strong patent and copyright protection on video games: people who really like old-fashioned videogames or people who want to play the best, most advanced video games?

How are parts a and b really the same question?

Question 13.26

6. Common sense might say that a monopolist would produce more output than a competitive industry facing the same marginal costs. After all, if you’re making a profit, you want to sell as much as you can, don’t you? What’s wrong with this line of reasoning? Why do monopolistic industries sell less than competitive industries?

Question 13.27

7. In the early part of the twentieth century, it was cheaper to travel by rail from New York to San Francisco than it was to travel from New York to Denver, even though the train to San Francisco would stop in Denver on the way.

Denver is a city in the mountains. Suggest alternate ways to get there from New York without taking the train.

San Francisco is a city on the Pacific Ocean. Suggest alternate ways to get there from New York without taking the train.

Why was San Francisco cheaper?

How is this story similar to the one told in this chapter about prices for flights from Washington, D.C., to either Dallas or San Francisco?

Question 13.28

8. This chapter told the story of how the 2000 California energy shortage was aggravated by price deregulation.

Suppose you are an entrepreneur who is interested in building a power plant to take advantage of the high prices for energy. Seeing rising energy costs, would price deregulation make it more or less likely you would build a new power plant? Why?

It’s very difficult to build and operate a new power plant largely because new plants have to comply with a long list of environmental and safety regulations. Compared with a world with fewer such regulations, how do these rules change the average cost of building and operating a power plant? Why?

Do these regulations make it more or less likely that you will build a new power plant? Why?

Do these regulations increase or decrease the market power of power plants that already exist?

Question 13.29

9. The lure of spices during the medieval period wasn’t driven merely by the desire to improve the taste of food (Europe produced saffron, thyme, bay leaves, oregano, and other spices for that). The lure of nutmeg, mace, and cloves came from their mystique. Spices became a symbol of prestige (just as Louis Vuitton and Ferrari are today). Most Europeans didn’t even know that they grew in the tiny chain of islands that is called the Spice Islands today.

Suppose you grow much of the spices in the Spice Islands. Knowing that few people could compete with you, how would you adjust your production to maximize your profits?

Suppose you heard rumors that the Europeans to whom you often sell are also becoming fascinated by the mechanical clock, a new invention that was spreading across Europe as a new novelty and as yet another symbol of prestige. How would this change your optimal production? Why?

Once Europeans made contact with the Americas, a new, high-status novelty arose: chocolate. Was this good news or bad news for you, the monopolist in the Spice Islands?

Question 13.30

10. China developed gunpowder, paper, the compass, water-driven spinning machines, and many other inventions long before its European counterparts. Yet the Chinese did not adopt cannons, industrialization, and many other applications until after the West did.

Suppose you are an inventor in ancient China and suddenly realize that the fireworks used for celebration could be enlarged into a functioning weapon. It would take time and money to develop, but you could easily sell the cutting-edge result to the government. If there is a strong patent system, would you put a big investment into developing this technology? Why or why not?

Suppose there were no patent system, but you could still sell your inventions to the government. Compared with a world with a good patent law, would you be more inclined, less inclined, or about equally inclined to invest in technological development? Why?

CHALLENGES

Question 13.31

1.

For the following three cases, calculate

The marginal revenue curve

The level of output where MR = MC (i.e., set the equation from item i equal to marginal cost and solve for Q)

The profit-maximizing price (i.e., plug your answer from equation ii into the demand curve)

Total revenue and total cost at this level of output (something you learned in Chapter 11)

What entrepreneurs really care about—total profit

Case A: Demand: P = 50 – Q Fixed cost = 100 Marginal cost = 10

Case B: Demand: P = 100 – 2Q Fixed cost = 100 Marginal cost = 10

Case C: Demand: P = 100 – 2Q Fixed cost = 100 Marginal cost = 20

Page 256What’s the markup in each case? Measure it two ways: first in dollars, as price minus marginal cost, and then as a percentage markup ([100 × (P – MC)/MC, reported as a percent]).

If you solved part b correctly, you found that when costs rose from case B to case C, the monopolist’s optimal price increased. Why didn’t the monopolist charge that same higher price when costs were lower? After all, it’s a monopolist, so it can charge what price they want. Explain in language that your grandmother could understand.

Question 13.32

2. In Challenges question 1, what was the deadweight loss of monopoly in each of the three cases? (Hint: Where does the marginal cost curve cross the demand curve? The same place it does under competition.) Is this number measured in dollars, in units of the good, or in some other way?

Question 13.33

3.

In 2006, Medicare Part D was created to subsidize spending on prescription drugs. What effect would you expect this expansion to have on pharmaceutical prices? What principle in the chapter would explain this result?

Given your answer in part a, what effect would you predict on pharmaceutical research and development?

Whatever answer you gave in part a, can you think of an argument for the opposite prediction? (Hint: In writing the Part D law, Congress said that subsidized drug plans must cover all pharmaceuticals in some “protected” classes, such as AIDS drugs, but that in other areas subsidized plans could pick and choose which drugs to offer. Understanding this difference may lead to different predictions.)

Question 13.34

4. In 1983, Congress passed the Orphan Drug Act, which gave firms that developed pharmaceuticals to treat rare diseases (diseases with U.S. patient populations of 200,000 people or fewer) the exclusive rights to sell their pharmaceutical for seven years, basically an extended patent life. In other words, the act gave greater market power to pharmaceutical firms who developed drugs for rare diseases. Perhaps surprisingly, a patient organization, the National Organization for Rare Disorders (NORD), lobbied for the act. Why would a patient group lobby for an act that would increase the price of pharmaceuticals to its members? Why do you think the act was specifically for rare diseases?

Question 13.35

5. For Kremer’s patent buyout proposal (mentioned in the chapter) to work, the government needs to pay a price that’s high enough to encourage pharmaceutical companies to develop new drugs. How can the government find out the right price? Through an auction, of course. In Kremer’s plan, it works roughly like this: The government announces that it will hold an auction the next time that a company invents a powerful anti-AIDS drug. Once the drug has been invented and thoroughly tested, the government holds the auction. Many firms compete in the auction—just like on eBay—and the highest bid wins. Now comes the twist: After the auction ends, a government employee rolls a six-sided die. If it comes up “1,” then the highest bidder gets the patent, it pays off the inventor, and it’s free to charge the monopoly price. If the die comes up “2” through “6,” then the government pays the inventor whatever the highest bid was, and then it tears up the patent. The auction had to be held to figure out how much to pay, but most of the time it’s the government that does the paying. Similarly, most of the time, citizens get to pay marginal cost for the drug, but one-sixth of all new drugs will still charge the monopoly price.

In your opinion, would taxpayers be willing to pay for this?

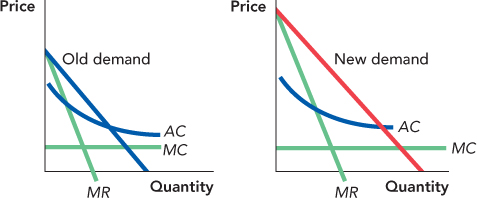

Using Figure 13.5 to guide your answer, what polygon(s) would these firms’ bid be equal to?

If the government wins the die roll, what net benefits do consumers get, using Figure 13.5’s polygons as your answer? (Be sure to subtract the cost of the auction!)

Question 13.36

6.

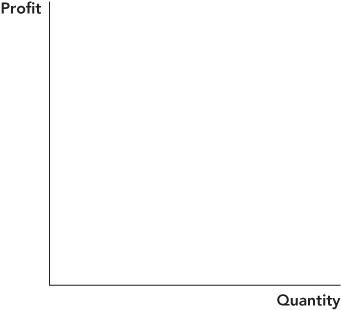

Let’s imagine that the firm with cost curves illustrated in the left panel of the following figure is a large cable TV provider. Assuming that the firm is free to maximize profit, label the profit-maximizing price, quantity, and the firm’s profit.

Now assume that the firm is regulated and that the regulator sets the price so that the firm earns a normal (zero) profit. What price does the regulator set and what quantity does the firm sell? (Label this price and quantity on the diagram.)

Which price and quantity pair do consumers prefer, that in part a or b? Do consumers benefit from price regulation?

Imagine that the cable TV provider can invest in fiber optic cable (high-definition), better programming, movie downloading, or some other service that increases the demand for the product, as shown in the right panel. If the firm were regulated as in part b, do you think it would be more or less likely to make these investments?

Given your answer in part d, revisit the question of price regulation and make an argument that price regulation could harm consumers once you take into account dynamic factors. Would this argument apply to all consumers or just some? If so, which ones?

WORK IT OUT

Earlier we mentioned the special case of a monopoly where MC = 0. Let’s find the firm’s best choice when more goods can be produced at no extra cost. Since so much e-commerce is close to this model—where the fixed cost of inventing the product and satisfying government regulators is the only cost that matters—the MC = 0 case will be more important in the future than it was in the past. In each case, be sure to see whether profits are positive! If the “optimal” level of profit is negative, then the monopoly should never start up in the first place; that’s the only way it can avoid paying the fixed cost.

P = 200 – Q Fixed cost = 1,000

P = 4,000 – Q Fixed cost = 900,000 (Driving the point home from part a.)

P = 120 – 12Q Fixed cost = 1,000