The Costs of Monopoly: Deadweight Loss

What’s wrong with monopoly? The question may seem absurd—isn’t it the high prices? Not so fast. The high price is bad for consumers, but it’s good for the monopolist. And what’s so special about consumers? Monopolists are people, too. So if we want to discover whether monopoly is good or bad, we need to count the gains to the monopolist equally with the losses to consumers. It turns out, however, that the monopolist gains less from monopoly pricing than the consumer loses. So monopolies are bad—they are bad because, compared with competition, monopolies reduce total surplus, the total gains from trade (consumer surplus plus producer surplus).

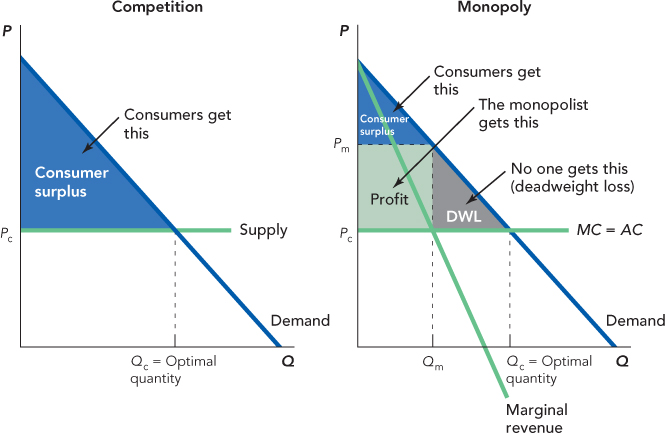

In Figure 13.5, we compare total surplus under competition with total surplus under monopoly. In the left panel, the competitive equilibrium price and quantity are Pc and Qc. We also label Qc the optimal quantity because it is the quantity that maximizes total surplus (recall from Chapter 4 that a competitive market maximizes total surplus). For simplicity, we assume a constant cost industry so the supply curve is flat (MC = AC) and producer surplus is zero. Total surplus is thus the same as consumer surplus and is shown by the blue triangle.

FIGURE 13.5

The right panel shows how a monopolist with the same costs would behave. Setting MR = MC, the monopolist produces Qm, which is much less than Qc, and prices at Pm. Consumer surplus is now the much smaller blue triangle. Now here is the key point: Some of the consumer surplus has been transferred to the monopolist as profit, the green area. But some of the consumer surplus is not transferred; it goes to neither the consumers nor to the monopolist; it goes to no one and is lost. We call the lost consumer surplus deadweight loss.

CHECK YOURSELF

Question 13.3

Does the monopolist price its product above or below the price of a competitive firm?

Does the monopolist price its product above or below the price of a competitive firm?

Question 13.4

Does the monopolist produce more or less than competitive firms? Why?

Does the monopolist produce more or less than competitive firms? Why?

To better understand deadweight loss, remember that the height of the demand curve tells you how much consumers are willing to pay for the good, and the height of the marginal cost curve tells you the cost of producing the good. Now notice that in between the amount that the monopolist produces, Qm, and the amount that would be produced under competition, Qc, the demand curve is above the marginal cost curve. In other words, consumers value the units between Qm and Qc more than their cost; so if these units were produced, total surplus would increase. But the monopolist does not produce these units. Why not? Because to sell these units, the monopolist would have to lower its price; and if it did so, the increase in revenue would not cover the increase in costs, that is, MR would be less than MC, so the monopolist’s profit would decrease.

Let’s look at deadweight loss in practice. GlaxoSmithKline prices Combivir at $12.50 a pill, the profit-maximizing price. There are plenty of consumers who can’t pay $12.50 a pill but would gladly pay more than the marginal cost of 50 cents a pill. Deadweight loss is the value of the Combivir sales that do not occur because the monopoly price is above the competitive price.