Government Policy toward Cartels and Oligopolies

Most cartels have been illegal in the United States since the Sherman Antitrust Act of 1890. (“Trust” is simply an old word for monopoly. The antitrust laws give the government the power to prohibit or regulate business practices that may be anticompetitive.) In the early 1990s, for example, four firms controlled 95% of the world market for lysine, an amino acid used to promote growth in pigs, chickens, and cattle. The firms—Archer Daniels Midland (USA), Ajinomoto (Japan), Kyowa Hakko Kogyo (Japan), and Sewon America Inc. (South Korea)—held secret meetings around the world at which they agreed to act in unison to reduce quantity and raise prices.

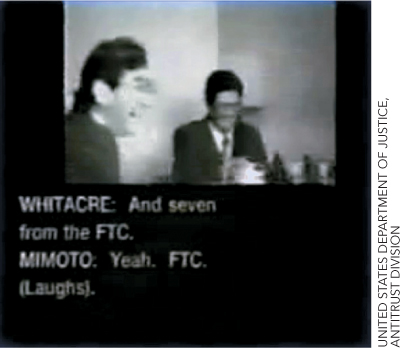

What the conspirators didn’t know was that one of them was a mole. A high-ranking executive at ADM informed the FBI of the cartel. Working with FBI equipment, the mole videotaped meetings at which the conspirators discussed how to split the market and keep prices high.

With the evidence in hand, the FBI and the Department of Justice put the conspirators on trial. Three executives of Archer Daniels Midland, including the vice president, Michael D. Andreas, were fined and imprisoned. One of the Japanese executives was also sentenced to prison, but he fled the country and is currently a fugitive from U.S. law.

More generally, the antitrust laws in the United States and similar laws in Europe can be used to block mergers or even to break up very large firms. In the 1970s, for example, AT&T was the sole provider of telephone service throughout the United States. That particular monopoly was legally sanctioned but in due time the government changed its mind, and in 1974 the antitrust division of the Department of Justice sued AT&T. The lawsuit led to the breakup of AT&T into seven independent companies in 1984. The breakup of AT&T increased the number of new entrants into the industry, providing a spur to companies such as Sprint and MCI. The Department of Justice continues to regulate the phone industry. In 2011, for example, the division blocked a proposed merger between AT&T and T-Mobile out of fear that such a merger would diminish competitive pressure.

Government-Supported Cartels

Governments don’t always prosecute cartels or break down barriers to entry. In fact, sometimes governments reduce competition and create barriers to entry. OPEC, for example, is a cartel of oil exporting governments. In fact, most successful cartels operate with clear legal and governmental backing. Governments are the ultimate cartel enforcers because they can throw cheaters in jail. In the United States, government-controlled milk cartels combine with subsidies and quotas to raise the price of milk. This cartel is extremely stable. Any seller who breaks it is fined or sent to jail. In the past, the U.S. government has supported cartels in coal mining, agriculture, medicine, and other areas; some but not all of these restrictions have been lifted.

Government-enforced monopolies and cartels are a serious problem facing poor nations today. They plague Mexico, Russia, Indonesia, most of the poor nations in Africa, and many other locales.

A government-supported cartel usually means higher prices, lower-quality service, and less innovation. People with new ideas find it harder or impossible to enter the market. Furthermore, people spend their energies trying to get monopoly or cartel privileges from governments, rather than innovating or finding new ways to service consumers. Governments become more corrupt. For these reasons, most economists generally oppose government-enforced cartels. Those cartels are put in place to serve special interests— usually the politically connected cartel members—rather than consumers or the general citizenry.